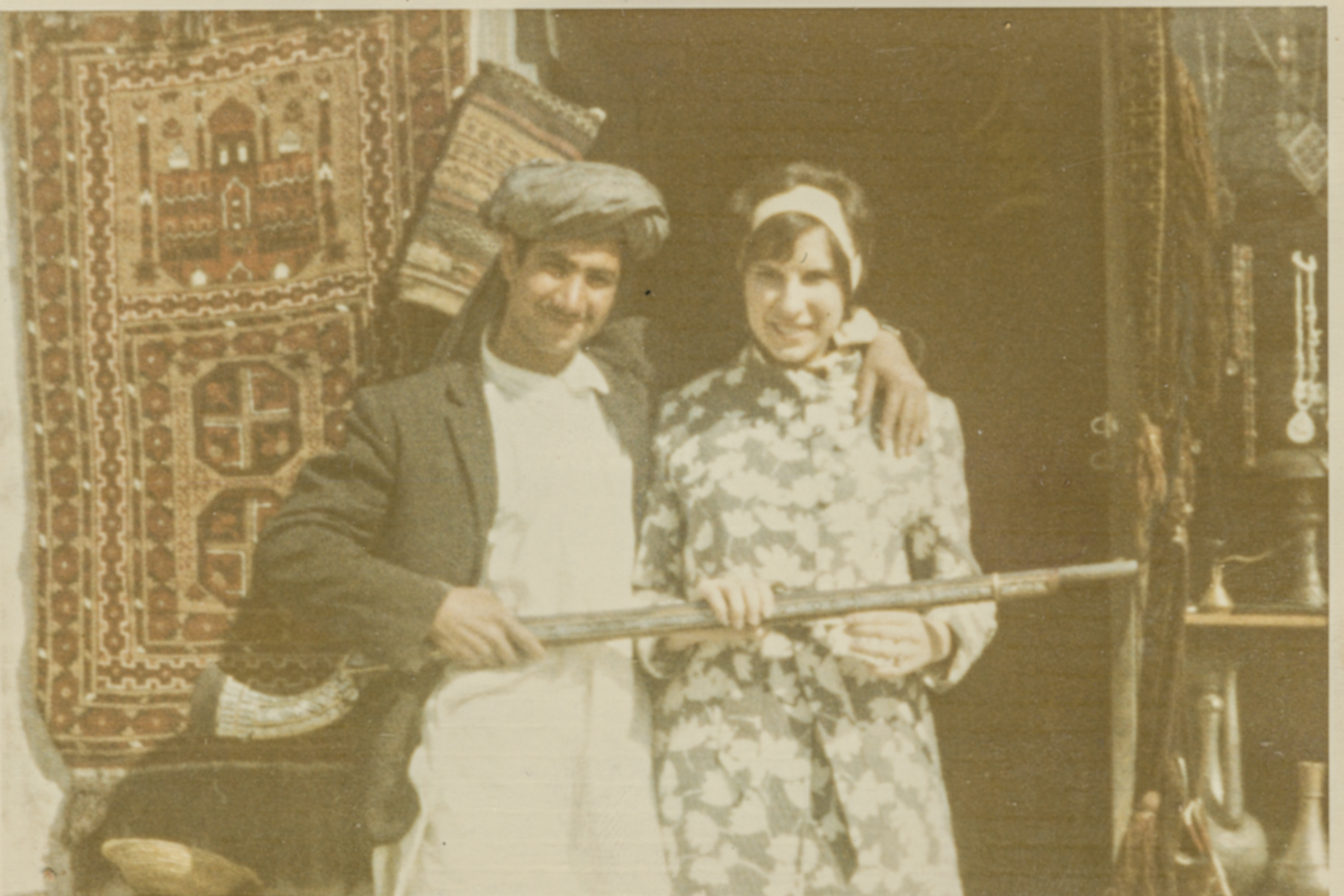

In 1970, after her parents sold their brake-repair business in Dallas, 15-year-old Jane Saginaw left Thomas Jefferson High School and went with her family on a monthslong trip to see the world. India, Afghanistan, Iran, Israel, Yugoslavia, Northern Europe. The journey was made more complicated by her wheelchair-bound mother, a polio survivor. But as this excerpt from Saginaw’s memoir shows, with her mother, everything was always more complicated.

En Route to New Delhi, India, February 3–4, 1970

Mom pointed past a three-inch plaster of Paris maharaja that balanced on the Air India counter and wagged a finger at the attendant who was leaning against the wooden console.

“No, sir,” she said. “I believe it is you that does not understand.”

Dad clenched the handlebars of her wheelchair and I stood to the side, ready to help, in the Leonardo da Vinci Airport in Rome. It was after midnight, and we had been waiting for well over an hour for this airline counter to open. We’d come early so that we would be the first passengers in line. “They must see me the very first thing, before they allow themselves to get distracted by something else,” Mom explained. She needed to secure the aisle bulkhead seat in order to extend her leg brace and be able to transfer in and out from her wheelchair.

“But, madam. I am afraid it is impossible,” the attendant said. “The bulkhead is set aside, reserved for our flight staff.” He pursed his lips and stood erect like a military man in his navy blue uniform with brass buttons and braided-cord epaulets. “And safety concerns, of course. I know you must understand.”

Dad pulled a handkerchief from the pocket of his slacks and wiped the back of his neck. Oh, of course. Safety was the first reason given whenever wheelchair access was refused. But Mom’s bulkhead seating did not affect anyone’s safety. And she had researched the issue thoroughly: there wasn’t an emergency passage at the bulkhead, no exit door, and no bathroom. I looked down the deserted airport corridor for my brother Harry. I should have wandered off with him when he left to find an International Herald Tribune for the flight. Harry knew how to make himself unavailable and avoid Mom’s confrontations. He had no difficulty walking away. Not like me. I always felt compelled to stick by Mom’s side like a foot soldier, as if my presence added credence to her pleas.

“Good man,” Mom said and adjusted her spine, lifting herself taller. “I cannot travel to India if I cannot sit at the bulkhead. Listen carefully, please. I reserved this seat months ago with your central booking office. Special arrangements were made in America. In New York City.” She removed airline tickets from the zippered side pocket of her purse and showed the agent where Seat 5A was typed onto the triplicate copies.

I stared at the maharaja doll on the counter as Mom’s impasse with the agent deepened. The cartoony figure stood in pointy shoes on a magic carpet and his head was wrapped in a red and white striped turban. One arm crossed his chest and he bowed, eyes closed. The maharaja’s mustache swept across his face in a black curve and covered the place where his mouth should have been. If he was our welcome to India, it seemed odd that his eyes were shut and his mouth was hidden from sight.

And now our Air India agent tightened his lips under his own mustache. He fumbled with the ticket before he placed it on the countertop and tapped it with his finger. He ignored Mom, looked decidedly over her head, and made eye contact with Dad.

“Can she walk, sir?” the agent asked my father.

Dad flushed. I curled my toes into my loafers and watched the color rise from under his collar to his hairline.

“Excuse me, sir,” Mom answered. “I can talk.” She squared her shoulders. “You understand, don’t you, sir? I talk. But to answer your question: no, I cannot walk.”

I searched the corridor again looking for Harry and noticed him sauntering in the distance without a newspaper or any apparent concern. I bit the ridge lining the inside of my cheek. I can talk was such a familiar refrain. I heard it often in Dallas. I even encouraged Mom to use the phrase sometimes in order to assert her authority in the face of people who would rather ignore her wheelchair arrangements. But we weren’t in Dallas now and Mom’s assertions sounded sadly ineffectual at this Air India counter in Rome.

I can talk.

Once a year every winter, Mom and I headed to downtown Dallas for the Neiman Marcus Last Call sale. Our excursion in February of 1969, just a year before our Air India encounter, began like so many others. I had walked into my parents’ bedroom early on a Saturday morning, just as Dad approached Mom at her dressing table, where she was staring into a mirror, dabbing on the finishing touches of her lipstick. Mom snapped the tube of red gloss closed just as Dad rotated her chair toward him and leaned over her lap.

“Excuse me, sir,” Mom answered. “I can talk.” She squared her shoulders. “I talk. But to answer your question: no, I cannot walk.”

“Be sure to leave something for the other customers,” he smiled and slipped a $100 bill under her blouse, beneath the strap of her bra. “You girls have fun downtown.”

When Mom arched her back and lifted her face toward his, Dad rested his hands on her armrests and drew himself closer. They wrinkled their noses and rubbed them together. A blue jay squawked on the porch outside their bedroom, and I watched it hop as I gazed through the half-drawn curtains. A swell rose through me. My parents delighted in each other. I was lucky that way.

Wallace greeted us at the loading dock when I pushed Mom from the Neiman Marcus parking garage, across Commerce Street, toward the store.

“I thought it was about time you two came to visit me,” he said, grinning and scooting his metal chair away from his security desk. I forced Mom’s chair up the steep incline of a concrete ramp and Wallace met us in front of the freight elevator. He stood attentively in his pressed khaki uniform and yanked down hard on a canvas strap that split open the scissor gate of the elevator with crashing, clanging drama.

“You know we wouldn’t disappoint you, Wallace,” Mom said with a lively smile. “Janie and I never miss a good sale.” She crossed her hands on top of her purse and stared straight ahead. We always entered the store from the service dock because stairs blocked our access at each street entrance. But Mom never seemed to mind the back-door entry. “We polios aren’t like other people,” she used to tell me. “We are quick adapters.” True, and maybe part of what made polios different from others was the way they accepted the attention they garnered. Mom rather liked the attentive service she received from Wallace.

Wallace unhitched the iron safety gate and I turned Mom’s chair around and backed her into the freight elevator. The lift’s worn wooden floor creaked. Cardboard boxes marked FRAGILE! and Made in Italy had been stacked to the ceiling on our right. I imagined wrapped porcelain dishes inside, teapots with painted songbirds and pagodas. I rubbed the back of my hand against the sequined chiffon dresses that hung on a rack to our left. Yellow. Pink. Aqua. Who wore those evening gowns anymore?

The elevator jolted to a stop and the doors screeched when Wallace heaved them apart. “All right,” he said. “Ground floor.” He held his hand out in a sweeping gesture as if he were a white-gloved operator in charge of a customer elevator inside the store. I liked Wallace’s good spirit. I liked the freight area too, with unpacked luxuries mysteriously organized. I wished I could hold back and stay behind the scenes of the store. But I turned Mom’s wheelchair toward the stockroom and said goodbye to Wallace.

The stockroom aisles were cramped and narrow. I had to be careful with Mom’s chair, rounding corners slowly past the merchandise and mannequins. A dark-suited salesman was busy in one row, bent onto a knee, sorting boxes of shoes and marking down the prices with a red pencil. “Excuse me. Excuse me, please,” Mom said to him, pointing her red fingernail into the air. The man stood up and shoved his boxes to one side making room for us to pass. “This area is actually off limits to customers,” he huffed. “Well, thank you, sir,” Mom replied. “We appreciate you making an exception for us this morning.” I pushed ahead, winding our way to the front of the stockroom, where I tapped the rubber tips of the wheelchair’s foot pedals onto the bottom of a double door. It swung open on its hinges, parting like a theater curtain.

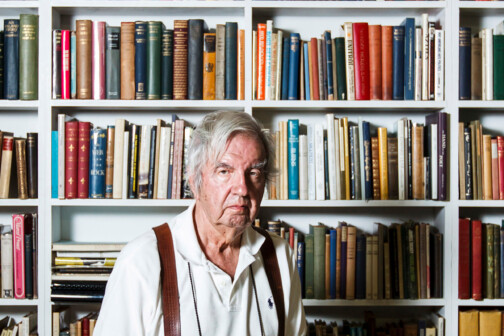

There was Stanley Marcus! He stood in front of the ground-floor elevators in a starched white shirt and navy pinstriped suit. Like a gentleman from decades past, he had a clipped silver beard and wore a red and white polka-dot tie with a matching kerchief folded into his breast pocket. Marcus made a point to greet his customers as the elevator doors opened. “Welcome to Neiman Marcus, ladies,” he’d repeat again and again, one hand relaxed to his side, the other resting atop a glass display table. When he noticed Mom and me entering the sales floor from the stockroom, he drew an arm to his chest and walked in our direction. His eyes sparkled like his pinky ring.

“Dear Rose,” he said. “Welcome to the store!”

Mom extended a hand, “Good to see you, Stanley!”

The wheelchair was no impediment to Stanley Marcus. He acted as if he was preparing to kiss her hand when he bent over Mom’s armrest in a slight bow. He reached out and cupped her hand between his and held it for a long moment. This man who hobnobbed with Coco Chanel and Elizabeth Arden, Salvatore Ferragamo and Yves Saint Laurent, who entertained Lady Bird Johnson and dined in the circles of European royalty, focused his undivided attention on Mom. She may as well have been a Hollywood icon and the rest of the store could have faded away. Mom was in his spotlight.

“It’s always such a pleasure to see you here,” Marcus said. He straightened his back and glanced fleetingly at the ceiling of the store. “You know, Rose, I’d like to figure out a way to build a discreet ramp of some sort at the front entrance here. You don’t need to come in the back way like that.”

There was Stanley Marcus! His eyes sparkled like his pinky ring. “Dear Rose,” he said. “Welcome to the store!”

Mom removed her hand from Marcus’ hold and placed it back on her lap. “Oh, Stanley,” she said, widening her grin. “It’s really not a problem.” She looked up and over her shoulder in my direction. “I have my daughter here to help.”

Marcus fluttered his eyelashes at me, and I felt the color drain from my face. Mom’s logic was absurd. I don’t need special arrangements; I have my daughter. Was I her special arrangement that negated the need for other plans? Or was I a given accommodation, taken for granted, so that nobody else need be bothered? In any case, Marcus seemed to recognize my predicament. It was hard for me to look his way.

“A striking girl,” Marcus said to Mom and raised his eyebrows. “Lots of natural style there. She greatly resembles Barbra Streisand, I think.” He smiled at me.

I pulled at the bottom of my skirt. Stanley Marcus wasn’t the first person to compare me to Barbra Streisand. Lots of people made the association. My dark hair was cut at an angle to my jaw, and I parted it on the left so that it fell into my right eye. The same cut as Streisand’s. We both had prominent noses and similarly shaped deep-set blue eyes. We even shared a birthday—April 24. Yet usually when people said I looked like Barbra Streisand, I’d stiffened at the comparison. Streisand was an attention grabber, a glamorous diva who zoomed to a spotlight and let her voice soar. I sidestepped attention. I kept my head low and my mouth shut. So why did I feel flattered now, when Stanley Marcus made the observation? Why was I flattered now, unable to hide my smile? Was he flirting with me? Did he recognize some fledging presence, a flare I was beginning to develop? He certainly saw in me something more than Mom’s accommodation. His interest lit a spark that burned in my cheeks.

“Thank you,” I said and pushed the hair from my eyes.

“She’s a good girl,” Mom followed up.

“I’d keep an eye on her,” Marcus said, and he winked at Mom before turning his attention to another customer.

Mom searched for a handbag while I wandered the aisles of the ground floor. Not much at Neiman Marcus really interested me. I wanted to dress like a hippie—bellbottoms and headscarves. I liked fringed ponchos more than the jewel-colored cashmere on display. I looked over at Mom as she pushed herself away from one sale table and toward another, her elbows jutting into the air as she rotated her wheels. It wasn’t often that I observed her from a distance. She had a sophisticated look in her green knit suit with the wide-open collar and that beige silk flower pinned high on her shoulder. Looking sharp was important to her. “It’s essential that I remain up to date,” she reminded me repeatedly when I took her shopping. “I don’t want people to think I’m sick.”

I walked over to her. “Find anything good?”

Shopping for purses was a challenge. Mom needed something that laid flat on her lap and wouldn’t slide off her legs. Something with a short handle because long straps fell from the side of her chair and tangled in her wheels. The style of the ’60s was shoulder straps and oversized hobo bags; the clutches and satchels she sought were difficult to find. But she enjoyed her stubborn search. Handbags were some the few items she could reach for and evaluate on her own. There was rare freedom in her ability to pick up the bags, rub the leather and examine the stitching, even if the search was in vain. She didn’t have to try on a handbag, after all.

“Let’s go up to the Zodiac Room now,” Mom said as she returned a purse to the sale table. “We’ll beat the lunch crowd.”

I pulled Mom backward into the elevator so that she would face its door, in the same direction as the other customers. A white-gloved elevator attendant punched in the number six on a brass plate. His manner was nothing like Wallace’s. He didn’t make eye contact or greet us in any way. He remembered us, though; we had been in his elevator dozens of times. He maintained a hushed decorum as the other shoppers huddled in the corner of the elevator, away from us, keeping a distance from Mom’s chair. Everyone stared at the numbers above the door as the lift rose in silence to the Zodiac Room.

I pushed Mom’s chair onto the thick blue carpet of the sixth floor. A long line had already formed for lunch, but Mom pointed me to the maître d’ at the front of the crowd.

“We can’t butt in like that, Mom,” I said, talking into the air over her head. “All these people are waiting their turn.”

“They don’t want me in line,” Mom said. “Believe me, the wheelchair is a nuisance to them all. Let’s talk to the maître d’.”

He stood stiffly behind a wooden pedestal in his dark suit and peered deeply into the reservation book as we approached.

“Excuse me,” Mom said. “We are two for lunch.”

“And do we have a reservation?”

“Not this afternoon. No.”

Mom waited calmly as he studied his book.

“I need an aisle seat with a removable chair,” she continued. “I stay in my wheelchair and don’t get out.”

I stared into the carpet at the side of her wheelchair. She always insisted upon particular seating arrangements in restaurants. At the movies, she requested early admission. Special access everywhere she went: the beauty parlor, our synagogue, the neighbor’s backyard patio. It was hard for me to bear when she was so demanding. But at the same time, I admired her tenacity. She was well aware that the wheelchair made most people nervous to be around and so she made it easier for them: she explained exactly how they could accommodate her needs. This maître d’ for example, had a choice: he could send Mom back down into the line, where customers might trip over her foot pedals and feel uncomfortable in her presence, or he could show us to a table with a removable seat on the aisle and redouble his attention on the needs of other diners.

“Follow me,” he said and ushered us through the tearoom. He slid away an aisle chair from a table for two. “Enjoy.” He smiled and I couldn’t tell if he was sarcastic.

Chicken consommé steamed in demitasse cups and strawberry butter melted on our popovers. “There’s always an extra table,” Mom explained, half-justifying her behavior. “It’s in his interest, believe me, to get me seated quickly and out of the way.” I bent my head into the oversized menu and studied my choices.

Helen Corbitt, the Neiman Marcus celebrity chef, strolled among the tables greeting customers in her apron. She rested her fingertips on the tablecloth near the blue crystals in our sugar bowl. “Mrs. Saginaw, so good to see you,” she said with a charming lilt that echoed Stanley Marcus’s. “I’m happy to see that you and your daughter are becoming such regulars with us. Enjoy lunch and come back soon.” Mom beamed at this competent woman and complimented her on the lightness of the lobster soufflé. “Bon appétit.” Corbitt smiled and moved away.

“Now that’s a fine woman,” Mom said. “Very professional. She knows exactly what her job is.”

And I knew my job as well. Before we left the store, Mom would want me to help her shop. The requirements were exacting: Mom needed long pleated skirts that covered her leg brace and loosely fitted tops that would stretch across her double-D chest and allow her arms freedom to push the wheelchair. No slacks. No straight skirts. Nothing short. Nothing loosely woven that might snag on her equipment. All of these needs during a time when pantsuits and miniskirts were the fashion. My job was to help her select modern outfits so that she didn’t look sick.

A saleswoman approached us in the Better Dresses department. She was wearing low-slung flare pants and a tight-fitting button-front blouse that pulled across her chest. She looked like a model from the cover of Vogue with her shoulder-length blond hair and thick black mascara. “Can I help you?” she asked as she sorted hangers and rearranged clothes on a metal rack loaded with marked-down merchandise.

“Yes, please,” Mom said. “I’m looking for something with a full skirt. I need something long and pleated that covers my knees.”

I was standing behind the wheelchair and watched as the woman turned our way and then looked over Mom’s head, directly at me. My fists tightened on Mom’s handlebars when she flipped her hair from one shoulder and asked, “What size does she wear?” I returned her gaze but refused to answer. I bumped my knee into the back of Mom’s seat, instead, nudging her to speak. Come on, Mom, don’t let her get away with that attitude. Stanley Marcus wouldn’t stand for such poor customer service. Tell her that you can talk for yourself. Come on! Show her, Mom!

“I’m a size 16,” Mom said, decidedly.

The saleswoman batted her lashes at Mom and then looked right back up at me. I widened my eyes: She’s your customer. I felt sorry for the woman in a way. She looked trapped, standing between the stuffed racks of clothes, not knowing which way to turn or how to get away from us. Maybe she had never been around a wheelchair before. I rolled the chair a little closer to her in a misplaced gesture of my annoyance. I didn’t think she intended to be insulting. But I wasn’t about to rescue her.

“And I can talk,” Mom continued. “I can talk, but I can’t walk.” “Can she wear pants?” the saleswoman asked me.

“No! She. Can’t. Wear. Pants. My mother wears a leg brace, and she needs a long skirt.”

“I’m sorry,” the saleswoman said.

I’d had enough. We were never going to find what Mom needed anyway. I jerked Mom’s wheelchair away from the clothes racks and pushed her to the elevator. Mom and I didn’t speak as we descended to the ground floor and trailed back through the stockroom to the freight elevator. I was relieved that we couldn’t see each other’s faces. I knew Mom was embarrassed—more for me, probably, than for herself. And I felt bad for her. It was a complex dynamic: she had her dignity to maintain. Was it more of an affront to be overly assertive and make people around her uncomfortable or to allow herself to be overlooked and treated as if she were invisible? I just didn’t want to think about the situation. The woman was stupid, that’s all, inexperienced. Let’s go home.

But that shopping expedition was a year ago. Now, in Rome, nobody cared whether Mom could talk. I had no desire to encourage her to assert herself here. This Air India attendant was not a department store salesman and the question at hand was not the availability of pleated skirts, or even her dignity. If this man wouldn’t let her board the plane and sit at the bulkhead, we would need to turn back and our trip to India would be canceled.

“Seat 5A?”

“Yes, Seat 5A. I must sit at the bulkhead, sir.”

I dropped my head and wandered away to join Harry.

Two men from the baggage department rolled a narrow chair down the airport corridor. Seatbelts dangled from the chair’s sides and the sound of the metal bouncing and scraping on the floor caught my attention. I looked over at Harry and grinned: “It looks like we’re getting on an airplane.”

We followed the men back in the direction of the Air India counter. The sight of that empty chair on its miniature wheels was as familiar to me as the roaring sound of an airplane’s engine. The chair was covered in navy blue vinyl and had a high back that was stiff like a hospital gurney. There were no arm rails or handles attached to its sides, and the width was the exact dimension of an airplane aisle. Mom hated being transported up the stairs of an airplane in those skinny insubstantial chairs. The lack of any security on the sides left her vulnerable to a fall, and she was delegated to the care of baggage carriers. As the men rattled the chair down the deserted hallway, they looked more like an emergency crew hurrying to rescue an accident victim than they did airline assistants called upon to aid a passenger.

“She was in rare form,” I said to Harry as we walked. “She was more insistent than I’ve ever seen her. I don’t think the guy from the airlines knew what to do with her.”

“Yeah,” Harry said, rubbing the side of his beard. “You know, not everyone thinks Mom is the center of the world.”

The mustached man with the braided-cord epaulets was leaning on his counter behind the miniature maharaja. He gathered some papers together, stepped from behind his booth, and escorted the four of us out of the airport and onto the tarmac. His heels clicked with authority. The baggage attendants followed behind with the narrow chair and joined us where we huddled near the wheels of the airplane. A steep flight of aluminum stairs led from the tarmac to the opened cabin of our flight to India.

“Well, all right,” Mom said and she bit the top of her lip.

She took a deep breath and handed me her purse. Harry and I stepped away as the two men approached her side and aligned the armless chair parallel to hers. Dad stood behind Mom, stabilizing her wheels, clenching his hands on her handlebars, as she crossed her forearms over her chest and dug her fingernails into her upper arms. She stared steely-eyed a few inches in front of her as each man jabbed one hand under her armpit and thrust his other beneath one of her knees. Her neck stiffened when they scooped her into the air and Dad pulled the wheelchair out from under her. Mom hung, suspended in midair. There was a slight breeze and her long skirt flapped against the tarmac.

I pressed her purse into my chest. There wasn’t anything that I could do to help. If those men dropped Mom, if they stumbled in the dark or misaligned her body so that she was off balance when they settled her into the armless chair, we would just pick her up off the ground and begin again. We would start all over. We would make this work.

“Hey, Mom!” I called over to her. “We’re going to India!”

The men hoisted her higher into the air before they lowered her onto the gurney chair. Mom kept her arms crossed. There was nothing else to hold on to.

“India, Mom!”

One of the men tipped the chair back onto its tiny rear wheels, circled it to the airplane, and began lugging Mom backward up the stairs. Dad remained on the tarmac with Harry and me, and the three of us watched her ascend. She was nervous. She was off balance. She was determined to get on this flight to New Delhi. I noticed the sweat dripping from Dad’s sideburns as he tightened his squeeze on the handlebars of Mom’s empty chair. But when I looked up at Mom’s slow and wobbly ascent, I saw that she was gently lifted and being cared for. From where I stood, she looked regal.

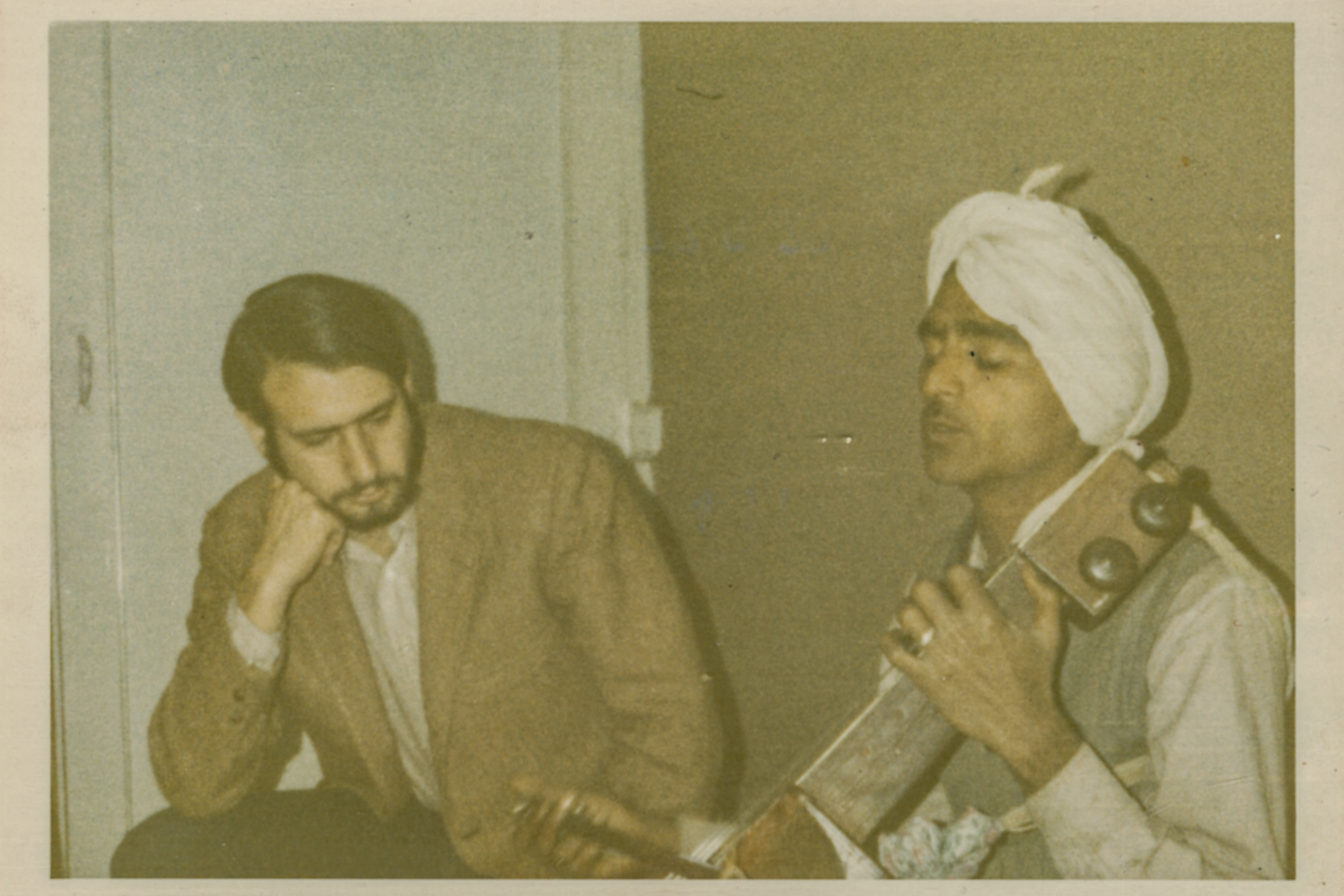

Mom settled into seat 5A and Dad stowed her wheelchair behind the pilot’s seat in the cockpit before he took his place next to her by the window. Harry strayed to the back of the plane and chatted with a flight attendant about finding an empty row where he could stretch out for the night. I took my assigned seat at the bulkhead across the aisle from Mom’s and buckled my seatbelt. Sitar music was piped in over the speaker system and I loosened the Peter Max scarf in my hair. India was as far from Dallas as any place I could imagine. I didn’t know what to expect, but I couldn’t wait to get there. The airplane gained altitude and I watched the colors of the sky outside my window undulate in violet and tangerine as the sunrise and sunset traded places.

An airline attendant approached. She held a tray with miniature orange marigolds arranged along its border, and she offered me a warm washcloth and a drink of ice water. She wore thick black eyeliner that curled up toward her temples and a hot pink sari that exposed part of her midriff. There was elegance about her, slowness to her gestures that I had never witnessed before. I felt almost embarrassed by her gentle attention. The pilot began flight announcements in Hindi, and I smiled when I realized that I knew what he was talking about, even though I didn’t understand his words. I looked across the aisle to Mom and Dad. They were sharing a scotch and soda and holding hands.

When the lights in the cabin dimmed, I switched on my reading lamp and pulled a paperback from my carry-on bag. The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test by Tom Wolfe. I had picked out the book at Taylor’s in Dallas and thought it was the perfect choice for our trip—the tale of a journey into the unknown. Wolfe told the story of the author Ken Kesey and his entourage, the Merry Pranksters. It was a wacked-out narrative about hippies and LSD, about parties on a Day-Glo-painted bus called Furthur, and a philosophy of interconnectedness called “intersubjectivity.” Kesey and the Pranksters coined a motto: You are either on the bus, or off the bus. Perfect! This is how I thought about my family as we began our journey: Mom and Dad and Harry and I were in it together, whatever “it” turned out to be. I crossed my legs and read on.

“Jane?”

Mom’s voice was a whisper and I ignored it. “Janie—sweetheart.”

I bored my index finger into the page of my book in a display of my reading concentration. Mexico? You’re kidding. Kesey and the Pranksters were going to cross that bus into Mexico with all the drugs they carried onboard? No! It won’t work! They can’t do it!

Mom reached across the aisle and cupped her hand on my arm above the elbow. I kept my finger on the page and I turned my face toward hers. Her eyes bulged and her skin looked ashen, even in the dark. She had straightened her leg brace and extended it toward the bulkhead, angled it into the aisle. She was poised to heave herself onto her brace and stand.

“What are you doing, Mom?”

“I need to pish.”

I looked over at Dad, snoring at her side.

“Oh, no. Can’t you hold it?”

“No,” she said. “You don’t understand. I need to go.”

I looked from the bulkhead up the aisle through the first-class cabin. There was a narrow door and a little step that led up to the bathroom. No way. Even if I could manage to get Mom up there— grasping the back of the seats, gripping onto my arm, swinging her braced leg—there was no way that Mom could fit through that little door. I looked back at her and the pupils of her eyes had contracted to the size of pinpoints.

How could she do this? We were heading out halfway around the world on a trip that she had planned down to every detail. She had stair counts and elevator widths and bed sizes memorized. She knew the dates we were to arrive and the names of our local contacts and the sights we would see at each of our destinations. How could she board an overnight flight and not consider access to the bathroom? And why was it that this toilet emergency suddenly became my problem to solve?

My index finger still marked my place in The Acid Test. I read the passage—“Intersubjectivity, as if our consciousnesses have opened up and flowed together.” The Pranksters insisted that their groups shared subjective experiences: I-am-you-and-you-are-me-and-we-are-all-together. I shoved my bookmark between the pages and closed the book. There must be something I could do. How could I abandon Mom?

The lights were switched off in the first-class cabin. I unhitched my seatbelt and snuck up to the bathroom with my carry-on bag. When I entered the tiny cabin, I stuffed a roll of toilet paper into my bag and flushed the toilet as if I had used it. I returned to Mom and handed her the paper.

“Hold this,” I said.

“What do we do?” she asked and released her leg brace.

An airsickness bag was filed into the bulkhead between flight magazines. I wiggled it free and examined it: an orange paisley design with exotic print that said Air India. The inside was coated with a thin plastic lining. If the bag could hold airsickness, it could surely hold a stream of urine. I passed the bag to Mom, and she held it for a moment without looking up. Then she turned her face toward mine and we smiled at each other until our smiles turned to giggles in a moment of recognition. What did we recognize if not our tacit intersubjectivity?

“Everybody’s sleeping,” I said and shrugged.

Mom forced her hips to the edge of the seat. She lifted her leg brace at the knee and moved it to the right, forming an opened V in front of her. The airsickness bag disappeared under her long, pleated skirt and she stared blankly into the bulkhead. I stood in the aisle, my back to my mother, and shielded her in the dark.