On February 5, Mayor Eric Johnson wanted to share some good news about crime numbers in Dallas. In his weekly email newsletter and in a post on Medium, he included a photo of himself hugging police Chief Eddie García. The chief was seated at a desk, looking down at crime data. The mayor, standing behind García, was leaning in to hug him, draped over the city’s top cop like a shawl.

Along with the photo, Johnson included a chart created by the Major Cities Chiefs Association, a police organization that García serves as president. The chart presented Dallas as the only large American city where all types of violent crime had declined over the previous two years. Johnson wanted to show people that the two public officials are so aligned in their efforts, and so successful in getting results, that the mayor had to hug the chief.

The image itself was inelegant. Hugs are better when both people are standing. But the message was clear. Yet six days elapsed with no local news coverage of the rankings. So Johnson took to Twitter.

“Our local media have no interest in reporting on this data, which is why you haven’t heard about it,” he wrote. Reporters with the Dallas Morning News, WFAA, Fox 4, KRLD, and NBC 5 responded with links to stories about Dallas’ declining violent crimes—but they didn’t mention the other nine cities in the chart.

Johnson then tweeted an adage about defensiveness he’d learned from his grandmother: if you throw a rock into a pack of dogs, the one that gets hit will yelp. “Them hit dogs still hollerin’,” the mayor wrote. He added that journalistic “quality has fallen off a cliff” and called it “pathetic.”

Them hit dogs still hollerin’! And still clearly unable or unwilling to read carefully a simple tweet. Explains why the media is where it is in terms of public opinion: the quality has fallen off a cliff. Pathetic.

— Mayor Eric L. Johnson (@Johnson4Dallas) February 11, 2023

Here’s the thing about that chart: the ranking was bogus. Comparing one city’s crime numbers to another’s is a reductive exercise that ignores how data are collected and fails to tell the real story about how things are going. Plus, the FBI recently modernized how it collects data. Its new system does away with what it called the “hierarchy rule,” where departments were basically allowed to juke the stats on a technicality. Meaning, if a robbery goes bad and someone ends up dead, police departments filed only the most severe charge—murder—and ignored the others. Now every crime in an incident is tracked and submitted to the feds. Dallas follows this process, but four of the 10 cities in the mayor’s chart do not.

Promoting that ranking was political boosterism that obscures what we should be analyzing and discussing: what about Dallas’ new approach to curbing violence is working and what is not? Because the department’s data do indeed show progress.

To understand what is happening with crime in Dallas, we should start in 2019. That year, murders in Dallas spiked to a level not seen in two decades. After Johnson won his seat in a runoff that summer, he inherited a violent crime rate that had jumped by 14 percent year over year. In 2020, it increased another 5 percent. According to the Dallas Police Department, the city closed 2020 with 254 murders, the most since 1998.

City officials were desperate. The violence figured prominently in headlines. In the summer of 2019, after two men fired into the wrong apartment and killed a 9-year-old girl, former Dallas police Chief Reneé Hall requested help from the Texas Department of Public Safety. State troopers poured into South Dallas. Over seven weeks, DPS made more than 12,500 traffic stops. In one case, a driver who failed to signal a left turn fled from troopers, who gave chase. The driver was shot and killed after exiting his vehicle with a gun.

Activists and elected officials—including that neighborhood’s councilman, Adam Bazaldua, and County Commissioner John Wiley Price—had had enough. District Attorney John Creuzot told reporters that the city needed a “recalculation” to make the streets safer, that “a taillight out is not going to drive down the murder rate.”

But all the while, something important was happening behind the scenes. Shortly after becoming mayor, Johnson created the Task Force on Safe Communities, a panel of 16 smart people including data researchers (Alan Cohen, of the local data analysis nonprofit the Child Poverty Action Lab), the future Dallas ISD superintendent (Stephanie Elizalde), and a UTD criminologist whom President Joe Biden would later appoint to be the head of the Bureau of Justice Statistics (Alex Piquero). It also included activists, developers, and clergy.

The task force produced a report that delved into the neighborhoods where violent crime is most common and made four suggestions. The first step was to begin investing in these areas, starting with simple things such as improving lighting, fixing up abandoned buildings, cleaning vacant lots, and improving infrastructure. The report recommended forming partnerships with DISD and community members to help kids “pause before they act.”

Shortly after the task force completed its work, Chief Hall resigned, and the city manager hired Eddie García. He was a cop’s cop out of San Jose who spoke of the importance of using data and evidence to address violence. One of his first decisions was to deputize UT San Antonio criminologist Mike Smith with creating a violent crime plan.

“Crime is concentrated,” Smith told me when I called him for this story. “Violent crime typically happens in a relatively small number of places in urban environments. A small number of offenders create most of your violent crime. What that tells you: police don’t have to be everywhere to control violent crime.”

Next month will mark two years since the city rolled out this crime plan. The police department divided the city into a little more than 101,000 individual tracts, each about the size of a football field. Every 60 days, the department identifies the 50 tracts with the most murders, robberies, and aggravated assaults. It then dispatches patrol officers, who sit in their cruisers and flash their blues and reds for 15 minutes at times when the data show crime is most likely.

Community members see a change on the ground. “Chief Hall would have officers in the area, but they wouldn’t be in the proximity of the people as a force. They may be around the corner,” says Changa Higgins, an activist who was part of the mayor’s task force. “García will put five officers in a parking lot of a nightclub.”

Smith the criminologist says the goal is to “make those officers as visible as they possibly can.” The data tell them where to go. “In Dallas, less than 5 percent of the grids produce all of the violent crime,” Smith says. The police strategy isn’t the same in every neighborhood. For instance, entertainment districts such as Deep Ellum require different strategies than where crime is most concentrated.

The plan also includes tracking repeat offenders and making them aware of the severe punishment they’re likely to face if they again break the law—and then offering them job training and other resources. This is called “focused deterrence,” and research from programs in Indianapolis, Chicago, New Orleans, and Seattle has recorded as high as a 34 percent decrease in repeated violent crimes, according to the chief’s crime plan. Focused deterrence will roll out later this year. The city manager also created the Office of Integrated Public Safety Solutions, which helps with blight remediation, code enforcement, data analysis, and mental health calls.

Smith says concentrated poverty is the strongest community-level predictor of violent crime, which is why it’s important that the response to it does not come only from police. The Child Poverty Action Lab uses something called risk-terrain modeling, which identifies physical traits that are common near violence—the exact things the mayor’s task force suggested. Take the intersection of Malcolm X Boulevard and Marburg Street, in South Dallas. A violent crime involving a gun was 564 times more likely to happen there than in the entire Southeast Patrol Division.

CPAL worked alongside the nonprofit Better Block and mutual aid organizations to transform a vacant lot at the intersection into a painted, programmed plaza for three months in the summer of 2022. Compared to 2019, there was a 55 percent reduction in overall crime at that tract and a 20 percent decrease in arrests. Violent crime declined 212 percent. What was once the most dangerous tract in the patrol division, in terms of gun violence, became the 463rd.

The city has invested more than $50 million into these initiatives—both in wages and capital improvements—targeted in neighborhoods where the risk-terrain modeling shows a need. Smith says the enforcement portion of the crime plan, the visible cops, has proven that crime typically subsides for 90 days after the cops leave a tract. Follow that up with public investments, and CPAL believes the success will extend even further.

Dallas has made strides since the crime plan’s implementation. In 2021, police recorded 222 homicides, a nearly 13 percent annual drop. In 2022, that number fell to 214. There were 315 fewer aggravated assaults last year compared to 2021, a drop of about 5 percent.

Most surprising, even as crime has dropped, so have arrests. They are down 19 percent since 2020: 9,886 then, 7,983 last year, showing that decreasing violent crime doesn’t necessitate putting more people behind bars.

But let’s say you still want to compare Dallas’ crime numbers with those in other cities. Bloomberg recently looked at the data on a per capita basis. Dallas’ homicide rate is the 18th highest among the country’s 50 largest cities. At 16.6 per 100,000 population, Dallas has a higher murder rate than Los Angeles, New York City, Fort Worth, and Miami.

There’s a lot of room for improvement, as Chief García likes to remind the City Council. The path forward is not on social media, comparing ourselves to other cities. It’s in the mirror, looking closely at what we’re doing, both wrong and right.

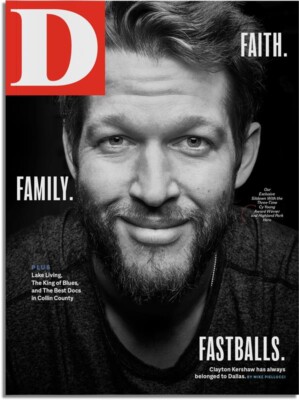

This article appeared in the April issue of D Magazine with the title “Dynamic Duo.” Write to [email protected].

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author