A dozen years ago, not long after their wedding at Highland Park Presbyterian Church, Ellen and Clayton Kershaw co-authored a book, Arise. Subtitled Live Out Your Faith and Dreams on Whatever Field You Find Yourself, it was part memoir, part sermon geared toward young adults hoping to walk in their faith and make a difference. In a chapter titled “Family’s What You Make It,” Clayton mapped out the world he and Ellen would create together. It contained nothing about the house they’d eventually own in the Park Cities, where they both grew up, but plenty about the home they’d make within it.

“Despite our different backgrounds, we agree on several things that we want to incorporate into our new family,” Clayton wrote. “Sunday night dinners are always important, and our home will feature a revolving door of people coming and going. Dogs are to be treated like humans, and card games are to be taken very seriously. We’ll play pranks and watch The Office before going to sleep. The last activity of the day will be praying together.”

Their kids are allergic to dogs, so the Kershaws currently own no pets. And card games, Ellen says with a grin, are “not good for us,” because they’re too competitive with each other. Clayton mostly pins this on Ellen. He admits to going hard at baseball and Ping-Pong, but that’s all. “I really don’t think I’m that competitive,” he claims, in an incredulous half-whisper. Everyone but Clayton rolls their eyes at that idea.

But the rest of that description of their future lives together? “Pretty darn close,” Ellen says.

The Kershaws were 23-year-old newlyweds when they wrote Arise with Ann Higginbottom, Ellen’s older sister (who is now also their neighbor two doors down). Clayton, the greatest Dallas-born athlete of his generation and perhaps every other, had just completed his breakout season with the Los Angeles Dodgers in what would become one of the most storied baseball careers in history. Three times he’s been named the best pitcher in the National League, and once, in 2014, the best player, period. Ellen, their philanthropic compass, had already begun her charity work in Zambia, which would become the cornerstone of Kershaw’s Challenge, their “faith-based, others-focused” charity that has raised more than $20 million to date for organizations spanning three countries.

Still, they saw a future, and they manifested it, all the way down to The Office reruns that remain a pillar of their TV diet. Soon, though, they’ll need to make some changes. Those young newlyweds are now 35-year-old parents of four, and another transition looms: the end of Clayton’s baseball career, which has thus far dictated the rhythm of their adulthood.

Some things will remain the same. Life together began in the Park Cities, and it will continue there, too, in a house that’s eight blocks from Ellen’s older brother, Jed, and just two from her childhood home, which is another eight from Clayton’s. They’ll order burgers from Chip’s and fajitas from Bandito’s Tex Mex Cantina in Snider Plaza. Clayton will make his customary soft drink runs to JD’s Chippery for Ellen and Ann. All six Kershaws will crowd into a pew at Highland Park Presbyterian. Their oldest children will continue to join their school-aged cousins in games of soccer or basketball in the Kershaws’ front yard before walking together to nearby Hyer Elementary for class. Same as it ever was.

But for the first time, all that activity will be accompanied by a question, one they don’t know when they’ll confront or how they’ll answer once it arrives.

What’s next?

The Kershaws do not live in a compound. Their house is not wreathed by any wrought-iron gate, and there are no Italian sports cars in the driveway. No exotic animals roam the property. Approach the front door, and you will find a passel of athletic equipment in the entryway. It just happens to be plastic and kid-size. Inside, the creams and grays of the first floor are classy and elegant, but similarly give little away. The TV mounted above the fireplace mantle is a size you upgrade from, not one you boast about. Aside from the custom gym built to replicate the one Clayton works out in at Dodger Stadium, every inch of the setup suggests “telecom vice president” more than “most accomplished starting pitcher in Major League Baseball.” If you live in University Park, you have almost certainly driven by the Kershaw house and with little notice.

The Kershaws are the very best kind of Park Cities story, a byproduct of its espoused ideals.

It’s all by design for the couple sitting for a rare interview together at a dark-stained kitchen table inside it. The couple who every year must be assured that other Los Angeles luminaries would be honored to host their charity Ping-Pong tournament. Whose friends know the story about Clayton enlisting a buddy to ask ESPN sideline reporter Suzy Kolber for a picture with them on a guys trip to the Super Bowl because Clayton was too shy to approach her himself. The couple leading every bit of the life they envisioned and more.

As such, the Kershaws are the very best kind of Park Cities story, a byproduct of its espoused ideals. The mythology that surrounds Highland Park and University Park is that they are unlike anywhere else in Dallas, hamlets of God and family tucked into the heart of a vast metropolis, where neighbors still check on each other and kids still roam the streets carefree. “Very much like Mayberry,” Ellen says. You’ll find all of it in the love story of Clayton Kershaw and Ellen Melson.

They were friends first, elementary-school buddies who ran in the same crowd. Josh Meredith, Clayton’s childhood best friend and the best man in the Kershaws’ wedding, recalls a pack of about eight boys who “weren’t really cool enough to be doing crazy things on Fridays and Saturdays. So we just had a fun little group and found a cool group of girls that actually thought we were all right.”

When the boys weren’t playing baseball or football, they rotated between one another’s houses for video game marathons. (“Super Smash Bros.,” a 1999 Nintendo 64 game, was a particular favorite; Clayton played as Kirby, the pink blob.) Their preferred summer activity was pool hopping: wandering the neighborhood until they found a house with a swimming pool, whereupon they’d climb the fence and cannonball into the water, one by one. The girls, meanwhile, were on the Highland Park Belles and bonded over Oprah Winfrey, whose talk show they’d watch after school and compare notes on the following day at school. Bible study was a staple. The boys and girls often gathered at the Melson house, with its chocolate fountain and secluded third floor, where Ellen’s mother, Leslie, kept an open door and promised a spot at the dinner table to whoever walked through it.

“When I’d go over there for dinner, there’d be 15 people. I don’t even know if they knew who they were,” Clayton says of Leslie and her husband, Jim. “That was so admirable.”

Those days left an imprint on the couple—and a blueprint for who they would become. When they began dating, after Clayton asked Ellen to be his girlfriend between classes during their freshman year, it would be almost another year before they’d spend any time together alone. Talk to them for any amount of time and that should not come as a surprise. They are most comfortable in a community, and the beating heart of that community is the people they’ve known prior to Clayton-and-Ellen becoming a proper noun. They remain tight with many members of their middle school crew, and Clayton is one of nine Highland Park guys in a group text, a crew so close that they monitor each other’s locations on the Find My app.

Clayton and his mother, Marianne, were folded into Melson family trips a year after Clayton and Ellen began dating. Leslie made sure Clayton had his own Christmas stocking in the Melson house before he and Ellen graduated from Highland Park. “We were all like, ‘Well, he’s in, so you need to figure this out,’ ” her sister Ann says, with a laugh, of her family’s advice to Ellen once they saw it on the mantle.

Not that anyone doubted they would. There was never any drama: no on-again, off-again saga. Not even when they lived on opposite schedules and opposite ends of the country while she was in college at Texas A&M and he was marooned in Midland, Michigan, as a minor leaguer. They got by on long emails and short phone calls. She made ballpark visits in the summer. He attended football games and sorority invites during the fall and winter, always brushing off inquiries of what college he attended with a simple “I don’t go to school.” Themed parties were their Super Bowl, peaking when they dressed as the Griswolds from Christmas Vacation.

Different as they are, they just fit. Ellen is their sun, warm and inviting, who brightens everyone around her and around whom everyone wants to orbit. “There’s no one that I am more excited to tell if something exciting has happened to me,” says Shay King, one of the couple’s closest friends and the development director at Kershaw’s Challenge. “It becomes real when I tell Ellen.” Her heart for people—her eagerness to make everyone feel important, like they belong—captivated Clayton before any other quality. “That amazing woman has never met a stranger,” says Josh Meredith.

Clayton is sturdy and self-effacing, with a wit dryer than a sack of silica packets. “He’s tough to impress,” Shay says. “When you make him laugh, you feel like you’re on top of the world.” Sand down the layers, though, and you’ll discover the goof, the prankster, the connector. “This is probably why God made him to play baseball,” Josh says. “If you’re going to be hanging out in a dugout with somebody for nine innings, trying to have fun, entertain yourselves and laugh, cheer on your team, and do all the things that are going to make the experience of baseball as good as it can get, Clayton’s who you want in your dugout.”

Ellen is the hands-off, multitasking mom, comfortable amid the chaos because she’s the third of four siblings who came of age in a house filled with comings and goings. Clayton is the self-professed helicopter dad—so locked in, so present. Befitting an only child raised by a single mother (his parents divorced when he was 10), he thrives on one-on-one time with their children, often stealing Charley away to hit golf balls or take Cali out on daddy-daughter dates when he worries he hasn’t connected with them enough lately.

“She says everything is going to work out,” Clayton says.

“And he’s the risk manager,” Ellen adds.

They draw strength from that divergence. And, Josh says, “The way they play off of each other, they just bring more and more of their excellent qualities out.” Ellen is the great listener in Clayton’s life, the first person with whom he felt comfortable revealing all sides of himself. He teaches her to be her most authentic self, that it’s OK to be honest about her feelings—“ ‘Blunt’ would be a harsher word,” Clayton deadpans—instead of blurring the line between welcoming and people-pleasing.

They come through for their people. When their friend Shay’s first marriage dissolved, they invited her to live and travel with them for an entire spring to escape the aftermath of the divorce. And when Shay remarried during the height of the pandemic, just a week after Ellen’s mom passed away from cancer in early 2021, there were the Kershaws. Clayton delivered a handwritten letter and his beige suit matched her bridesmaids’ dresses.

In another life, this would be their only focal point: loving each other, and their children, and all the members of their swelling tribe. They’d quietly carve out a life in the Park Cities the way their parents did before them, giving back where they could, the years rolling by with no need to update the paradigm they settled on as those 23-year-old newlyweds.

Instead, a funny thing happened, a development neither of them foresaw: Clayton Kershaw learned how to throw a baseball better than almost everyone in history.

This was always a possibility, however slim. The Dodgers selected him seventh overall in the 2006 Major League Baseball draft for a reason. They paid him $2.3 million to forgo his college commitment to A&M, where he would have joined Ellen in school, to turn pro. The number staggered him. Weeks earlier, when his agent told him over lunch at Chip’s how much he stood to make, he reacted by setting his half-eaten burger down and holding his head in his hands, murmuring, “That can’t be right,” over and over.

But with several dozen players being added to every team’s minor league system each year, the baseball draft is less a crapshoot than a prayer. This is a sport that eats its young. Clayton conquered the odds through meticulousness. His weekly maintenance included bullpen sessions—throwing between actual games—consisting of exactly 34 pitches broken down into eight segments. Days he pitched were, and are, fiercely regimented. For a typical 7:10 pm start, he leaves for the ballpark at 12:53. Pregame stretch begins at 6:23, which is followed by an allotted four minutes of Zen time at 6:36, catch at 6:40, and one final bullpen session at 6:47 or 6:48 (there’s wiggle room there).

There was never any drama: no on-again, off-again saga. Not even when they lived on opposite schedules and opposite ends of the country.

“You pitch every fifth day, and if you lose, you’re disappointed,” Clayton says. “If you win, you’re happy. And you keep going. That was it.”

He was a major-league regular by 20. At 21, he was already among the game’s best pitchers. Two years later, in 2011, he made the first of nine All-Star games and won his first Cy Young Award, given to the best pitcher in each league. That kicked off a legendary run in which he became the first player ever to lead baseball in earned run average (the number of runs allowed per nine innings pitched) for four consecutive seasons. He captured the Cy Young in three of them, and was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player in 2014, making him the first pitcher to win the award in 46 years. The Dodgers rewarded him with a seven-year, $215 million contract, at the time the largest for a pitcher in baseball history.

He was suddenly 27 years old and on the fast track to immortality, his delivery as iconic as the windups of Nolan Ryan, Roger Clemens, Pedro Martínez, and Sandy Koufax. The simultaneous raising and lowering of his arms and right leg, as though the three limbs are tethered to the same marionette string. The bend in his left leg as he propels himself forward; the right arm lengthening, then contracting; the right leg clomping into the dirt. The torque in his left elbow as he maneuvers the baseball from his left kneecap up past the red numbering on his jersey, past his earlobe, past the brim of his Dodger-blue hat, until his torso dips and he snaps off one of his unholy trinity: the fastball, the curveball, or his money pitch, the slider. All three torture hitters, as much for their movement as Kershaw’s almost unparalleled ability to command them. Few players have ever been more feared.

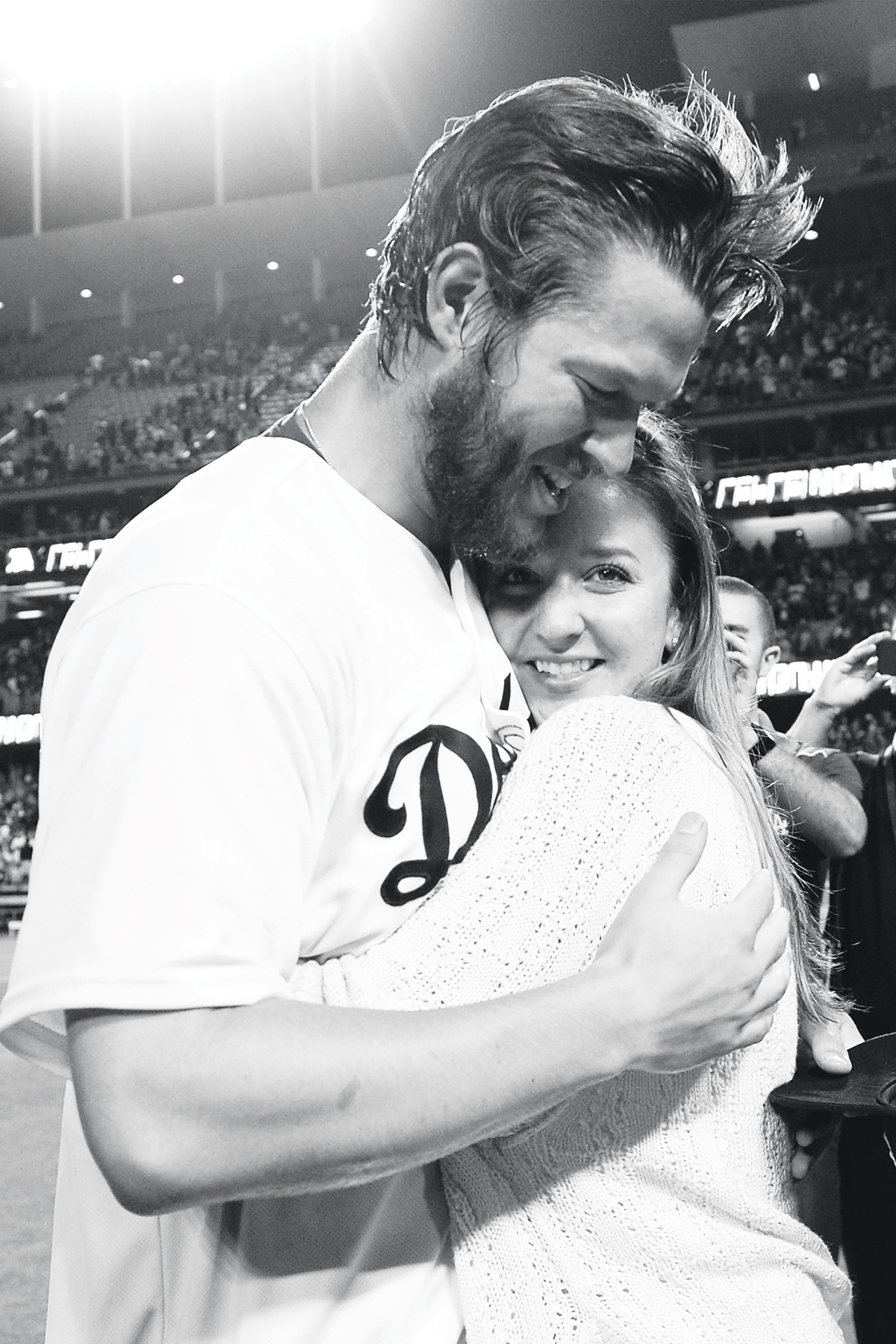

On it went, year after year, accolade after accolade, until somewhere along the way he became a mirror image of Dirk Nowitzki, the unassuming maestro synonymous with one professional city while never ceasing to belong to the one he came from. And, after a half-decade of chasing a World Series, of absorbing nationwide bile each time the Dodgers failed, Clayton had his Dirk-esque redemption in 2020, winning his long-awaited ring in Arlington, at Globe Life Field, which hosted playoff games as a neutral site due to the pandemic. Among the indelible images was him hoisting his third child, 9-month-old Cooper, high into the air as he strode around the field in celebration, Ellen to his left with a gray Dodgers sweatshirt wrapped around her sky-blue jeans.

Here’s where the comparison stops: unlike Nowitzki and his wife, Jessica, the Kershaws refused to lay down roots anywhere other than their hometown. They could have purchased an estate in Santa Monica, or the Pacific Palisades, or wherever else they wanted in Los Angeles years ago, all the better to access the avenues athletic royalty have available to them in the country’s glitziest city. Setting aside how that wouldn’t be their style—the dining room table in their L.A. house is a Ping-Pong table—it’s also not where they’re meant to be.

“For us, it’s always been Dallas,” Clayton says. “That’s always been our choice.”

Their Los Angeles address has rotated, but they’ve steadily grown into their University Park home since they bought it a decade ago, their daughter Cali Ann followed by sons Charley, Cooper, and Chance. They’re baseball kids through and through, accustomed to life on the move. Summers are spent in Southern California, along with various other big-league cities on Dodgers road trips. Springs and early falls are back and forth between Dallas and Los Angeles.

That cannot last forever, and they know it. Nor can Clayton’s body. He has worked at a punishing pace; only three active pitchers have thrown more innings, all of whom are at least three years older than he is. The injuries began flaring up around 2016—his biceps, his shoulder, his forearm, and, perpetually, his back. None were enough to break him, but they have ground him down.

The winter of 2021–2022 might have been the nadir. Baseball was mired in a months-long labor stoppage, and he was perhaps the only player happy about it because the time off provided enough cover to conceal the amount of pain his pitching elbow gave him after missing two months of the 2021 season. It twinged when he twisted a doorknob. It ached when he washed his hair. He didn’t return to his peak until March, right around when the lockout ended and he was free to sign a new one-year contract with Los Angeles, hardly anyone the wiser that he spent most of the offseason wondering whether retirement had come for him rather than the other way around.

His elbow held up far better last season, his best in years. Still, he and Ellen decided to lean into the uncertainty instead of run from it. From now on, baseball goes a fresh one-year contract at a time. This will be their new normal. It could last for years. It could end in seven months.

Their barometer will be a series of what they call check marks. First, Clayton must be healthy. “No one wants to be around you when you’re hurt,” Ellen playfully chides him at the kitchen table. And the game still must be fun, which, as Clayton sees it, includes both team success and him playing a pivotal role in it. “If I’m pitching average, I don’t want to pitch,” he says.

L.A. is not where they’re meant to be. “For us, it’s always been Dallas,” Clayton says. “That’s always been our choice.”

Above all, the baseball lifestyle must continue to work for their family. By all accounts, the Kershaw kids are thriving, in no small part due to Ellen being the sort of mother who is not only capable of ferrying four children around the country but also one who embraces the adventure in doing so. “If Ellen’s not Ellen, it doesn’t work,” says her friend Shay. The kids are also getting older. Personalities are emerging. Memories are getting made. Clayton doesn’t want “the kiddos,” as he refers to them, to miss him the way he already misses them. The family has a rule that there must be a touch point at least once every seven days, no matter how demanding the Dodgers’ schedule is, and so his buddies in the group chat are accustomed to seeing his location appear in Dallas for 12 hours on an off day to take Cali Ann to Bible study or Charley to his soccer game, before flitting right back to Los Angeles. That can’t last forever, either.

“I know it gets harder and harder to make that decision to go back to L.A.,” Josh says. “I know it wears on him. And I know that he doesn’t want to miss those little special moments that can happen any and every day with your kids. He just doesn’t want to be a dad that’s not there for them.”

That’s where the final check mark comes in: he’ll only pitch for one of two teams, the Dodgers or the Texas Rangers. “Probably not the way an agent wants you to do it,” Clayton deadpans. But it fits where they are in their lives. One home or another—the city that nurtured them in adulthood or the city that raised them and is helping them raise another generation. Not long ago, there wouldn’t have been a conversation. The Dodgers have been baseball’s model franchise for a decade, a perennial contender that has won its division nine of the last 10 years and played for the World Series in three of them. The Rangers have been, well, the Rangers. But the gap is closing. Texas is on the upswing, adding Jacob deGrom, another of the game’s elite arms, one year after dropping a half-billion dollars on second baseman Marcus Semien and Clayton’s old teammate in Los Angeles, shortstop Corey Seager. Like the rest of the baseball world, he has taken notice.

“The only reason that’s even a consideration is because of the respect I have for the people within that group, especially now that Chris Young is there,” he says of the Rangers’ general manager, a fellow Highland Park alum. “I have a lot of respect for Corey and Marcus, and they just signed deGrom. I love all those guys. … I don’t want to go to a team that’s not going to be good. And I think the Rangers are on that path.”

Add in the allure of playing at home, where he could walk the kids to school each morning and hang out with Ellen on an off day, and his pal Josh says he “could totally see him figuring it out with the Rangers” before taking off his cleats for good. Maybe someday. For now, “with the history we have in L.A., I feel like you have to give that the first crack,” Clayton says, which led to a new one-year agreement with the Dodgers in October. After being one of the last marquee free agents to sign a season ago, he was among the first in 2023. “This year, the check marks were pretty easy,” he adds.

So was the exchange that sealed it. It came a few days after the season ended, with the nonchalance fostered between partners who know how to hear the unsaid after spending more than half their lives together.

“I kind of want to go back,” Clayton told Ellen.

“I do, too,” she replied.

And so together they’ll go, like always.

It’s sweatshirt weather on a Thursday night in early November, and the backyard at The Rustic is decorated like a Yellowstone set, dotted with hay bales and Pendleton blankets. Darius Rucker, the Hootie & the Blowfish lead singer turned country music star, plays to a crowd of about a thousand people straddling the line between Dallas chic and Old West theme park—Stetsons and puffer vests, cowboy boots and faux leather.

This is KC Live, the Dallas flagship event of Kershaw’s Challenge. For eight years, the benefit concert has raised money for a rotating cast of charities. The organization has evolved since its founding in 2011, when it raised money to build an orphanage in Zambia. Africa had captured Ellen’s heart ever since she watched an Oprah special about poverty on the continent as a teenager and made her first mission trip to Zambia at 18 years old.

“In the beginning,” Ellen says, “we were using his platform for my passion.”

By the end of the night, they’ll have raised $1.8 million, part of $3.2 million total raised in fiscal year 2022. Both are new records, according to sister Ann, the charity’s executive director. In the years since its founding, Kershaw’s Challenge has ballooned to work with organizations in Dallas, Los Angeles, Africa, and the Dominican Republic, the latter of which was driven by Clayton after years of bonding with Latin American teammates.

That’s in addition to the Kershaw Foundation, which is directly backed by the couple’s income and funds grants to a network of charities benefiting similar causes. The Kershaws pay all overhead to maintain the two organizations so that every donated penny—including their own annual contribution to Kershaw’s Challenge—can go to charity instead of expenses.

This, the Kershaws believe, is their purpose: the reason why Clayton was blessed with otherworldly talent, the reason they were brought together, and the reason they now possess such wealth.

“I always say, when you get a gift like being able to throw a baseball, I didn’t do anything to deserve that. It was just a gift given to me,” Clayton says. “So, how do you use that? I think that’s why God gave me Ellen, and I think that’s why she had that vision of Africa. I think it was all intertwined.”

If you want to know where that might take them after baseball, the best place to start parsing the possibilities is KC Live, for reasons that transcend the work itself. Kershaw’s Challenge stopped selling tickets to the public in 2021, which makes that 1,000-person crowd a vast web of family, friends, neighbors, acquaintances, classmates, churchmates. Fathers whose sons played with Clayton at Highland Park. Mothers who were friends with the Melsons. Kids who pool-hopped or watched Oprah with them.

“I feel like we really do have probably one degree of separation from the majority of people,” Clayton says.

This is as much a reunion as a charity event, an unofficial homecoming at the end of each baseball season. It’s where Ellen, the woman who has never met a stranger, works the microphone and holds court. More significantly, it’s where Clayton, the avatar of baseball intimidation, can shout-sing himself hoarse. He interjects himself into photos with Ellen and her girlfriends, tilts his head back and howls along to Rucker covering Garth Brooks’ “Friends in Low Places.” He closes out the evening playing auctioneer for a signed Rucker guitar, his raspy voice calling for bigger bids, exhorting the crowd to go higher, until it’s going once, going twice, sold. Plenty of people in Los Angeles have never known this Clayton Kershaw. Plenty of people in Dallas have never known a different one. Which, for him, makes this more than a return home. It’s a return to his most authentic self, the man he is when he’s free of the stress and anxiety that twists him into something harder every fifth day.

And so perhaps the answer to the Kershaws’ grand question is less about what than who. No one around Clayton imagines he’d stop pitching only to then throw himself into a demanding second career in a front office or a broadcast booth. He barely needs the game now, much less a facsimile of it. He has the kiddos to thank for that. They’ve mellowed him out.

“It’s been neat to see him naturally soften those edges,” Ann says. “It’s the same competitive guy. It’s just a guy that made chocolate chip pancakes and then left for the field.”

Clayton savors the off seasons, when his days are free to sling mashed potatoes during his regular cafeteria shifts at Hyer Elementary.

All going back to work would do is stand in the way of what makes him happiest: playing dad. He savors the off seasons, when his days are free to sling mashed potatoes during his regular cafeteria shifts at Hyer Elementary and he can join the moms of other students to help chaperone class field trips. Last February, Ellen felt her stomach drop when she picked up his call from a father-daughter dance he was attending with Cali Ann. “What’s wrong?” she demanded. Nothing at all. “I’m just having such a good time,” he gushed.

What’s next, then, is more of that guy.

More of Ellen keeping the door to the Kershaw house open, setting a place for any guest the way Leslie did before because, as dad Jim Melson beams, “Ellen is a clone of her mom,” in all the best ways.

More of Ellen and Clayton raising their kids in the traditions they cherish while also exposing them to a world—a Dallas—far broader than the Park Cities. Kershaw’s Challenge helps. The organization has partnered with groups such as Behind Every Door, For Oak Cliff, and Mercy Street Dallas, and Clayton and Ellen make a point of bringing their children with them into South and West Dallas whenever possible. The kids have attended a back-to-school backpack giveaway in South Dallas, while Charley participates in an annual baseball camp Clayton puts on in West Dallas. Perhaps they’ll see Clayton coach some teams down there, too. For now, he seems to have more of an appetite for that than committing to a post-playing career in baseball or pushing his sons into the sport. (Although Shay King says she definitely sees a world in which his daughter follows in her mom’s drill team footsteps, in which case “he will box out some moms to be in the front row for Cali’s dance recital.”)

More striving to be the sort of parents who lead their children to embrace endless possibilities, and who will embrace the inevitable questions that arise from them, all the way down to the faith that has served as the bedrock for three generations of Kershaws and Melsons in the Park Cities.

“Especially in this community, someone needs to tell your kids that you have to make that choice for yourself, what you’re going to believe,” Clayton says. “Being able to have that conversation and be like, Charley, or Cali, or whoever it is, ‘This is why we go to church on Sundays. This is what we believe. We’re going to take you with us, but ultimately, you have to make this choice for yourself about what you believe about this Jesus guy.’ Just having those conversations and being honest about it and having them make that decision for themselves when they’re old enough.”

It’s a challenge, to sustain that level of emotional availability and physical presence for four young people, who someday might travel different paths from both their parents and each other. There’s no telling what that will look like, either. That’s just as well. Ellen and Clayton Kershaw already know a thing or two about uncertain futures. And they also know that you can’t plan for everything. But you can come pretty darn close.

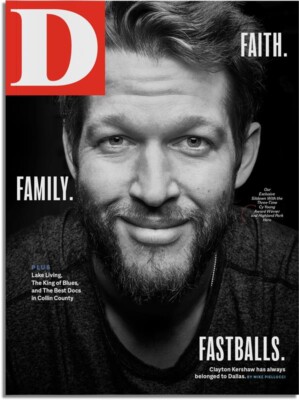

This story originally appeared in the April issue of D Magazine with the headline, “Faith, Family, and Fastballs.” Write to [email protected].

Author