There are agents in Hollywood who specialize in selling books to the movies, and I was sitting in the Beverly Hills office of such a person some years ago, discussing the prospects for a script I had written based on C.W. Smith’s 1983 novel, The Vestal Virgin Room, published by Atheneum. It was a wonderful tragicomic novel by a wonderful, sure to be famous Dallas author, about an endearing husband-and-wife lounge act playing Holiday Inns in Missouri but aiming for Vegas. The agent encouragingly mentioned several bankable actors and directors he was planning to send the script to but then said, “In the next draft, you have to make them less like losers,” the reference to Don and Dottie, the two main characters. Hollywood talking.

Don and Dottie were not losers, at least not to me, and I was pretty sure not to Charlie Smith, who created them. They were clearly talented if not destined for the big time, an ordinary American couple contending with life’s adversities and each other while mired in the shallows of show business. The agent’s failure to see the virtues in their humanity might partially explain why Universal or Warner Bros. never made a movie out of The Vestal Virgin Room, and I wonder what that agent might think of Charlie’s newest book, Girl Flees Circus, being published this month by the University of New Mexico Press. Once again, in this, his 10th novel, he is drawn to the struggles and longings of ordinary people, the denizens of a town in New Mexico so small it doesn’t have a name. The year is 1928, and the anonymous locals become characters in a drama set in motion by a mysterious teenage aviatrix who crash-lands her biplane on a main street, creating a sensation wholly unfamiliar to the outback hamlet. She turns out to have escaped from a flying circus, but who she is exactly and what she’s up to will not be revealed until we are first introduced to the complex relationships and surprising community she discovers while waiting for her aircraft to be repaired.

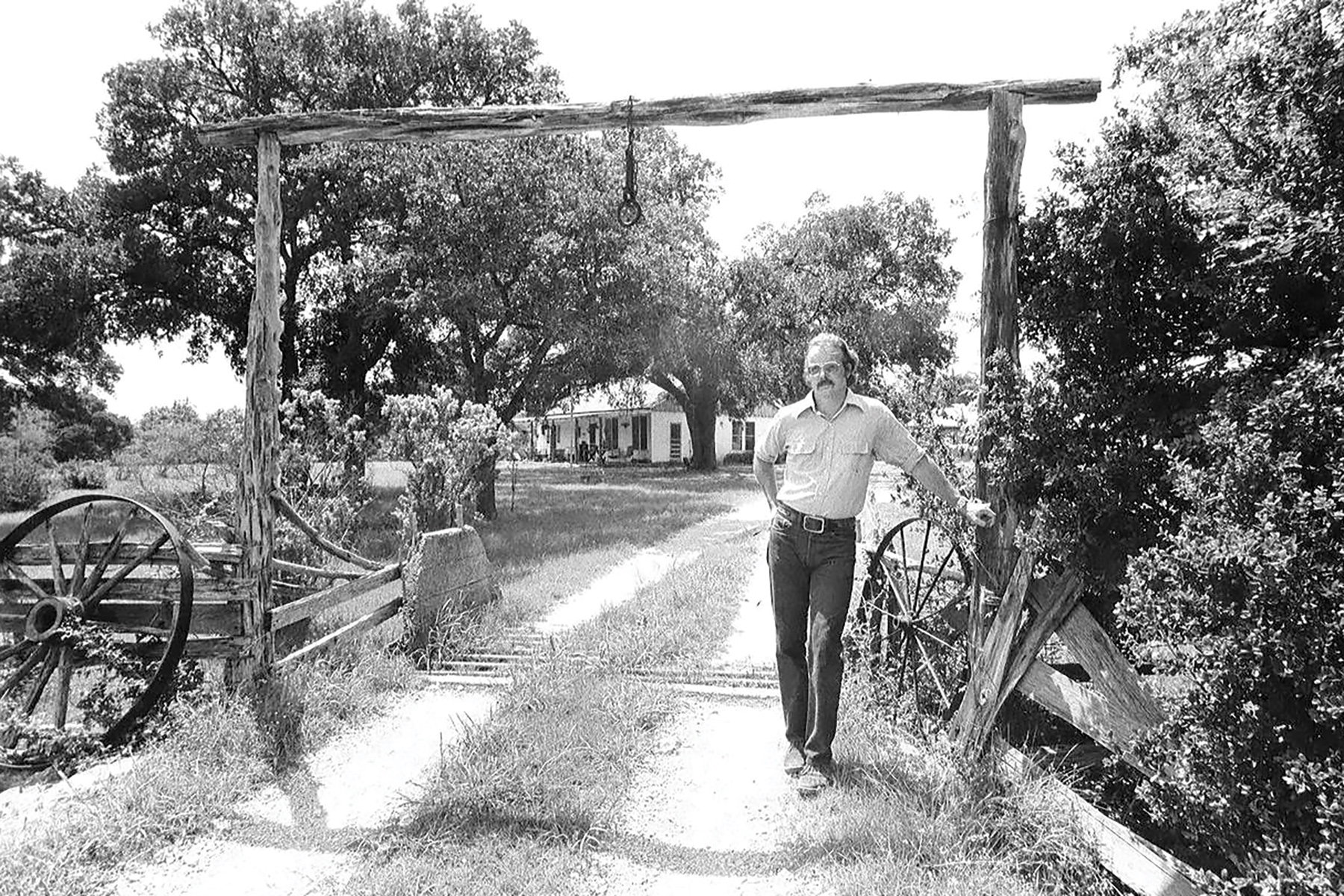

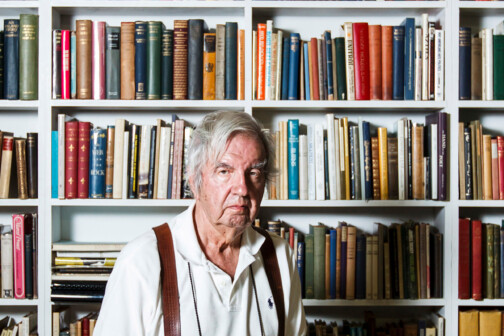

“I didn’t start out thinking about this, but after I began working on it, I began to realize that for me it’s a story about the West, about the transience of the West,” Charlie says to me one day in the living room of his house off Abrams, in the M Streets, where he has lived for 25 years with his wife, Marcia. He is in the emeritus stage of his career now, and what a career it has been: 13 books and every Texas literary prize and distinction within reach. “Nobody in that town is from there,” he says about the no-name locale in the book. “This is a result of my growing up in Hobbs, where nobody was from there. They all came because of the oil.”

Hobbs, New Mexico, only 12 miles west of the border with Texas, is part of the Permian Basin, and the discovery of oil there is a subplot in Girl Flees Circus. When the first well comes in, the way it’s described, as seen from the air, might surprise anyone who remembers the glory and romance of Giant: “[T]he inky fluid still spurting, the rig surrounded by trucks, tiny men carrying lanterns, and the huge dark stain spreading over the landscape like spilled paint, filling the arroyos, making rivulets and odiferous swamps … a hellish wetlands where no plant of animal could ever live.”

“I just accepted it for what it was,” Charlie says about the oil industry of his youth. “Everybody I knew, their parents worked for oil companies. I never questioned it really.” In the summers of high school and college, he worked as a roustabout on the oil fields, gaining hands-on experience he would later put to good use in his books, including this one.

You can know someone for decades and not know details about his childhood, his parents, where he came from and what made him who he is. This was the case with Charlie, but I decided the time had come to clear some of that up.

Charlie’s father, William, who lived to be 100 and died in 2017, was a natural gas engineer working for Gulf Oil, which kept him out of the service in WWII. Originally from Nashville, William was posted by Gulf to Corpus Christi, where Charlie was born the year before Pearl Harbor. His mother, Helen, who met William in Nashville, started her own company writing oil and gas reports for small producers. She also wrote poetry but showed it to no one. The family moved to various oil patches around the Southwest before getting to Hobbs, where they stayed and Charlie graduated from high school. “I treasure the childhood I had in that oilfield camp,” he says. “We were free-range kids. I was allowed to go my own way.”

In those years, the late ’50s, Charlie was more interested in jazz than literature, starting on the clarinet and moving to the saxophone. In high school, he played in various bands and discovered Dave Brubeck, Miles Davis, and Charlie Parker listening to WWL New Orleans. On a trip to New York City with his parents at 17, he went to Birdland and heard his first live jazz—the Maynard Ferguson big band and the Cannonball Adderley Quintet.

After graduating, he enrolled at what was then North Texas State in Denton (now UNT) “because it was the only public university where you could study jazz.” He played both alto and tenor sax in a jazz band there but was frustrated he couldn’t major in jazz, and after discovering the works of John Steinbeck and William Faulkner, he switched his major from music to English.

“I never read anything in high school that made me think I wanted to be a writer,” he says, the first time I have heard him mention this. But Steinbeck showed him the way in. “He wrote about people I felt I knew or had known.”

Charles Smith was too plain a byline, he figured, when he began to write fiction himself, so he substituted the initials C.W. (his middle name being William). He drew on his Southwestern youth in his first novel, Thin Men of Haddam (1973), about a Hispanic orphan raised in an Anglo family in New Mexico. It won various awards plus the Texas gold star from the Fort Worth Star-Telegram: “Perhaps the most auspicious debut for a Southwest writer since Larry McMurtry’s Horseman, Pass By.”

McMurtry, who graduated from North Texas a few years earlier, was not the touchstone for Charlie one might think. “I’ve read a lot of his books,” he says. “I like them. I never thought of him as a mentor. Or influence.”

“McMurtry got into film right away,” says the Houston writer and editor Babette Hale, whose recent short story collection won best new fiction prize from the Texas Institute of Letters. She refers to Hud and The Last Picture Show, popular movies that led people back to the books on which they were based and established McMurtry’s national reputation. Hale knew McMurtry when he was young and says, “It is like lightning striking,” when Hollywood puts your book on the big screen.

“Why the heck didn’t that happen?” she asks now, meaning fame, for Charlie. “I think for one thing, all his books are set in this part of the world, and that’s a limiter.” Hale edited and published Charlie’s 2001 novel, Gabriel’s Eye (Winedale), about a tragic romance between a Dallas high school student and his art teacher. “But he has all the tools. He’s terribly smooth, funny, warm. And he likes women.”

“Most of what I was reading was avant-garde and arch,” says Tom Stewart, then a young editor at Viking who discovered Thin Men of Haddam in the slush pile. “This was about real people.”

Charlie was writing in the tradition of realism he had absorbed from reading Steinbeck, Hemingway, John Dos Passos. “I was just following my basic instincts,” he says, not trying to be fashionable or calculating. He followed Stewart to Farrar, Strauss & Giroux for his second novel, Country Music, a coming-of-age story about a rough-cut Lothario who has to learn to live in a world where women are actually people. It garnered top reviews and testimonials to his uncommon gifts but did not hit the bestseller list. Playboy Productions optioned the book and paid him to come to Hollywood and write a screenplay, but, in 1978, he found himself in Dallas needing a job, two highly praised novels notwithstanding. He and his then wife, Gay Parrish, a North Texas theater major, had two kids. She got on at KXAS Channel 5 as a reporter and weekend anchor; Charlie inquired at the Dallas Times Herald, which was looking for a film critic. His credential was the Playboy Productions gig.

That’s where we met, at the Herald during its renaissance, a decade before it lost the newspaper war to the Dallas Morning News. I was the theater critic and he the film critic. In a feature section packed with good writers, Charlie stood out, a singular talent. He reviewed films with a sympathetic voice and fine eye (I can still recall his explaining the beauty of Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven), but he also did Sunday magazine features made of paragraphs you wanted to study if you were a journalist.

He fell in love with one of the feature writers there, Marcia Smith, and they have been together ever since.

Charlie left the Herald in 1980 to join the English faculty at SMU and teach creative writing. A few years later, I moved to California to take a job at the Los Angeles Herald Examiner. But we stayed in touch and later worked out a deal with his agents for me to adapt The Vestal Virgin Room, his third novel, the only one that’s about music (country music being a metaphorical title). I loved the book and believed Don and Dottie belonged in a movie that might make all the difference for Charlie, drawing deserved attention to the other books he kept writing.

“He’s wonderful with characters. He’s wonderful with prose,” says Stewart. “And these are the things he cares most about. He’s more interested in people and place than in plot.”

Jerry Whitus, a short story writer and former running partner of Charlie’s, remembers when the two of them rented offices in the same building on the edge of downtown Dallas to do their creative work. Whitus was impressed by how disciplined Charlie was, “doing all that research and not stopping to brood or question what he was up to, just doing it.” At the time, Charlie was working on Buffalo Nickel, the “big book” his New York agent had urged him to write, which turned out to be the epic saga of an early 20th-century Kiowa Indian who became an oil millionaire in Oklahoma and then a movie star in California, torn between two cultures. It was published in 1989 by Simon & Schuster and, though well received, did not become the bestseller he and his agent had envisioned.

The advance for Buffalo Nickel was big enough that he could have quit teaching at SMU. But he says he never considered it. He liked teaching. “I had the greatest job in the world,” he says. “I liked being around young people. I liked having colleagues. I liked the social life. Without that, I wouldn’t have had any.” He taught at SMU for 32 years, retiring in 2012.

After Buffalo Nickel, Charlie lost his marketability in Manhattan. He also lost his agent. TCU Press published four of his next five novels and a collection of short stories, Letters From the Horse Latitudes, that got a positive review in the New York Times from Benjamin Cheever. But it was still a university press, not considered the big leagues in the snobby world of publishing.

By the time I returned to Dallas, both Charlie and I were caring for elderly parents. We met occasionally for lunch at El Fenix on Northwest Highway to talk about this and other topics, remembering the high period of the Herald and the cast of characters we knew there. He gave me helpful notes on a manuscript I was working on and shared an early draft of Girl Flees Circus. Reading it, I was reminded of his uncanny ability, using an omniscient narrator, to pry open the hearts and minds of common people, in this case people from the 1920s—as disparate as a biracial middle-aged couple running the town’s only cafe, a sexually repressed schoolteacher from Cincinnati enchanted by the comely aviatrix, a forlorn shell-shock victim of WWI and the long-suffering nurse who marries him, a guileless 18-year-old quasi orphan who lives in a Comanche teepee and dreams of a career in radio, plus the young flier herself.

The idea for the book began with Charlie remembering that Amelia Earhart might have landed a plane in Hobbs in the 1920s during a cross-country flight. He thought the story was likely apocryphal, but after some research, found it to be true. It gave him the seed for the novel. “I just thought, I want to learn about other aviatrixes, and it turns out there were a lot them and they weren’t very well known,” he says.

He discovered that while Earhart was far and away the most famous, she was regarded as an average pilot by her peers and resented by many because she married a man rich enough to promote her into a celebrity. Charlie says, “I wanted to get away from writing about her and write about the generic women pilots instead—and where they came from.”

But of course. He wasn’t going to a fictionalize a star. And he was going to give equal time to the supporting cast in NoName, New Mexico, a band of humble outliers from the roaring twenties who live day to day almost like a family, helping each other with chores and challenges, and then pitch in to fix the damaged plane for the aviatrix at no charge. Such a different time and place. And one likely to be altered by the coming oil boom.

“I didn’t hide anything,” Charlie says when I ask if there is anything in Girl Flees Circus that his readers might miss. “I think people might not pick up on the transience, that being a theme of the West. The town has no name because it has no history. Everybody is always moving on.”

Ten novels, a memoir, a collection of short stories, and batch of essays about exploring Europe with Marcia. All published. Not bad. Nevertheless, he says, “I can’t think of a single book that I’ve written that I thought got its just due. But I’m not alone. Every writer imagines a tombstone that says on top ‘Underappreciated’ and on the bottom ‘Underrated.’

“On the other hand, I don’t do it because of that. However much success a book achieves is not the end goal. It’s what people miss when they say, ‘You ought to write a bestseller.’ My resistance to writing a bestseller is not that I don’t want to write a bestseller; it’s that I can’t write a bestseller. You are given by your temperament the kind of thing you can do. I always felt like I was given growing up in a small town in the West, and leaned on that as being a documentarian of the cultural mores and language and lifestyle and cuisine and everything there is to say about what it means to be alive in this place and time that I have lived in.”

Which speaks to why fiction matters in the first place, not to mention the unseen effort it takes to produce it, one sentence at a time.

By the way, The Vestal Virgin Room was optioned three more times, by three different Hollywood producers. I wasn’t the only one who saw something cinematic in it. I don’t know if any of those later scripts made Don and Dottie seem less like losers by giving them a hit record in the end. I guess that could still happen, but if it does, just know that it wasn’t me—or Charlie—who did it.

This story originally appeared in the September issue of D Magazine with the headline, “The Novelist Resigns Himself.” Write to [email protected].