Before a corporate relocation brought me to Dallas in 1992, I lived on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. A bookseller, an émigré from gentrifying Chelsea whose store rent had quadrupled, had set up his used merchandise on tables in front of my bank at West 72nd Street and Columbus Avenue. One day, he stood behind his table proudly displaying only one book for sale, a nearly 4-inch-thick hardcover Webster’s Third New International Dictionary Unabridged, often advertised as the largest, most comprehensive American dictionary in print. His bargain price: $30. A definite appeal to informed book buyers, but I had something in mind other than the acquisition of a 10-pound dictionary on the eve of a cross-country move.

I approached and asked if he knew of any libraries that bought audiotapes. I had heard some horror stories that cargo entrusted to Mayflower, my contracted mover, had inexplicably ended up in Alaska. Over the course of my career, I had interviewed some famous writers and wanted to put these tapes somewhere safe for the benefit of scholars, historians, and students before leaving town. The bookseller suggested Yale University’s oral archives.

I reached Yale’s Irving S. Gilmore Music Library and its curator of historical sound recordings, a man named Richard Warren, and offered him hours of audiotaped interviews with Pulitzer Prize winners, National Book Award winners, and others of comparable stature. He responded, “If the price is right, Yale will take it.” On Warren’s recommendation, the acquisition committee of Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library accepted the appraised value, and I was ready to take the train with 60 pounds of unedited interview tapes and associated papers in huge shopping bags, but the Beinecke curator declined. Instead, she sent the college limousine with the check for the pickup.

I didn’t have a car during the many years I lived in New York. My most prized possession was a blue Peugeot 10-speed bicycle. I rode it everywhere, including to the East Side townhouse of the editor of the Paris Review, George Plimpton, to discuss an interview I’d done with the Pulitzer poet Anne Sexton. George considered it one of the best pieces he’d ever published.

I rode my 10-speed Peugeot everywhere, including to the East Side townhouse of George Plimpton.

I also pedaled to the East Side for a Q&A with Tom Wolfe, fresh from the successful 1968 launch of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, about his time spent with Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters. I admired and sought to emulate his revolutionary Joycean stream-of-consciousness style. Not so much his proclivity to sprinkle his prose with esoteric anatomical terms for female genitalia. At the conclusion of our interview, he escorted me to my bike downstairs to watch me in my short shorts sling my leg over the seat before I rode away.

At the time of my move to Dallas, I was living in a second-floor, rent-controlled West 73rd Street brownstone just behind the Dakota, the first cooperative building above West 59th Street for the rich. I occupied the original foyer and parlor with its crown moldings, parquet floors, shuttered bay windows, and 12-foot-high ceiling. Half of a music room had been converted into a bathroom and a kitchen, with a sliding blind.

Periodically water would cascade down my bathroom walls from the overflowing bathtub of a fourth-floor neighbor’s apartment. A painter was imported from Brooklyn to repair the damage and was offered $25, which he refused even as he agreed to take the job. “Your landlord can’t pay for the quality of work I do,” he told me.

Such inconveniences could be easily suffered given the apartment’s location, a few blocks from heaping bins of fresh fruits and vegetables at Fairway, New York’s first roofed farmers market; walking distance from Lincoln Center’s Balanchine and New York Philharmonic performances; a one-stop express subway ride to the Broadway theater district. Best of all, half a block away, Central Park invited me to train competitively for long-distance road races and the New York City Marathon.

Back in The Day

Before Kevles moved to Dallas, she lived on the Upper West Side of Manhattan and wrote for such publications as the Paris Review, the Atlantic, and Harper’s Bazaar.

Bryn Mawr

Class of 1962: In college, Kevles got the impression that to be a writer, she’d have to live in Greenwich Village.

Millrose Games

Kevles interviews legendary chiropractor Dr. Seymour “Mac” Goldstein at the United States’ premier track and field event, the annual Millrose Games, held at Madison Square Garden since 1914.

Kevles interviews legendary chiropractor Dr. Seymour “Mac” Goldstein at the United States’ premier track and field event, the annual Millrose Games, held at Madison Square Garden since 1914.

Patchin Place, NYC

E.E. Cummings, whom Kevles once visited, lived here in Greenwich Village.

E.E. Cummings, whom Kevles once visited, lived here in Greenwich Village.

Runner’s World

Kevles finished ninth in her age group with

Kevles finished ninth in her age group with

a blistering 6:50 pace in the 10K L’eggs

Mini-Marathon, placing 77th out of 3,480 U.S. finishers.

I supported myself by serving as a contributing editor to Working Woman, the first magazine to celebrate women for their work outside of the home, and freelancing articles for the New York Times, the Atlantic, Esquire, New York, Harper’s Bazaar, People, and others. I also taught my craft at The New School and New York University.

The articles generated reams of research that I stored in brown cardboard R-Kive boxes that sat on custom-built wood shelves from the wainscot up, lining the walls of my foyer office. I worked on a 6-foot arts-and-crafts table I’d brought with me from my first apartment after college, a fifth-floor West Village walk-up. I had chosen the Village because of a misbegotten notion I’d picked up from courses on early-20th-century English at Bryn Mawr College that if you wanted to be a writer, you had to live in the Village. The walk-up was not far from Patchin Place, home of another idol, the poet E.E. Cummings, whom I once visited, and the East Village cafes where I read my poems. Allen Ginsberg once heard me read and quipped, “Why don’t you join the union?”

One of the archive boxes I feared would find its way to Alaska during my move contained my reporting on the Kennedy women. I’d done a Good Housekeeping cover story on Joan Kennedy published a month after Chappaquiddick and a Ladies’ Home Journal story on Eunice Kennedy Shriver apropos of her husband Sargent Shriver’s run for the 1976 Democratic presidential nomination. I had interviewed nearly three dozen Kennedy family members, family friends, politicians, Kennedy Foundation executives, and the Kennedy women themselves. Sen. Ted Kennedy’s office had given me a trove of original news articles. The John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library (as it was known then) was interested in that R-Kive box but didn’t want to pay anything. So I contacted the Sixth Floor Museum, which had been founded just a few years earlier. My phone call, oddly enough, was answered by someone at the Dallas Police Department. Perhaps they were still managing the crime scene? In any event, I reversed course and donated my materials to the Kennedy Library as a permission-restricted collection. Thanks to a happy alphabetical order, in the printed catalog for the Kennedy Library, the entry for The Barbara L. Kevles Personal Papers appears on the page following the entries for Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy and her son President John F. Kennedy.

I found a real estate agent to search for an apartment in North Texas. I told her I wanted crown moldings, a fireplace, and a storage facility for all my boxes. A few weeks before leaving town, during a run on Central Park’s lower loop, I encountered Fred Lebow. He had taken an exclusive race first run in 1970 by 55 runners around four loops of Central Park, expanded it in 1976 to all five New York City boroughs, slapped a banner on the finish line, invited the press, and created what we know now as the New York City Marathon. Fred was omnipotent in the running world. Once, at Tavern on the Green, an agent for the winner of the Peachtree Road Race tried to shake me down, charging me to interview his client for a national magazine. I said in a loud voice, “Fred said to give me the interview.” And he did—at no charge.

On my run in Central Park that day, I approached Fred and hugged him. This was most unusual for someone like me who doesn’t demonstrate affection in public. Over the years, though, I had interviewed this man many times, and he had given me contacts for many famous runners I’d written about over the years. Still hugging him, I kissed Fred on the cheek and said, “Thank you for promoting running and helping me live longer.” That was the last time I saw Fred alive. The man who had completed 69 marathons in 30 countries died of brain cancer two years later. His funeral cortège drove through Central Park several times on the way to the cemetery in homage to his achievements.

I contacted the Sixth Floor Museum, which had been founded a few years earlier. My call, oddly, was answered by the Dallas Police Department.

My boxes, all 100-plus of them, made it safely to Dallas. As did I. I’ll never forget when I arrived at my storage facility and discovered that my agent, Cheri Scallon, the salt of the earth, had already bought and assembled floor-to-ceiling metal shelves to hold them. Those archives helped sustain me.

During my short corporate stay, I received a letter from Laurence Leamer, who was writing his 1996 bestseller, The Kennedy Women: The Saga of an American Family. He wanted access to my papers at the Kennedy Library. As a national archive, the library believes in maximal equitable access to its holdings, but I hold a different view. I maintain copyright holders have the right to profit from the commercial use of their work, and permission-restricted collections enable them to do that. Kennedy sources told me Leamer hadn’t more than two hours of interview time with Eunice Kennedy Shriver. So I negotiated an access fee with Leamer and a per-word usage publication fee. When Leamer complained he couldn’t decipher my handwritten notes, I read them to him over the phone, and we both taped the readings.

In a letter of recommendation, Leamer later wrote, “I have found no one who has written with more depth and insight on the Kennedy women than Barbara Kevles. Her collection at the Kennedy Library … is a unique repositor of information.” My name appears on the first page of the acknowledgments for The Kennedy Women.

More or less, that is the improbable story of how my audiotaped interviews and allied papers came to comprise a collection at my alma mater. A chance encounter with a bookseller on the street started my sideline, as it were, as an archivist; a move to Dallas and a misdirected query to the Dallas Police Department led me to the Kennedy Library; and in the process of writing about both of those events for the Bryn Mawr Alumnae Bulletin, the college library director, James Tanis, contacted me because he wanted to be included in the article. He asked how many R-Kive boxes still resided on my metal shelves. For the next five years, he and I talked every April about what he might buy.

This spring, the college spent thousands of dollars to engage the services of a renowned audio preservationist named George Blood. He digitized nearly 40 tapes of my interviews with winners of Oscars, Emmys, and Grammys; the first Black champion of Wimbledon; pioneering politicians; and international diplomats. Bryn Mawr’s director of special collections, Eric Pumroy, said, “Barbara Kevles interviewed some of the most important women of American culture from the late 1960s through the 1970s.” All that work now belongs to The Barbara Lynne Kevles Papers and Recordings, which are permission restricted. However, I’ve written an introduction and finding aid that will go online this fall.

I spent this spring reviewing the digitized tapes, comparing them to their transcripts and over a thousand pages of handwritten interview notes that the Kennedy Library had photocopied, searching for elisions and omissions in the copied tapes. Approaching the interviews with a perspective of, in some cases, five decades removed, I discovered new revelations about these celebrities’ loves and work, and money’s influence on their lives.

Greatest Hits

Over the years, Kevles amassed a trove of reel-to-reel taped interviews with some of the most famous women of their times.

(1921-2009) sister of the 35th president

Eunice Kennedy Shriver

Her singular calling was to advocate for those with mental retardation (to use the terminology of the day). One night she asked her older brother, President John F. Kennedy, if he would be willing to appoint a presidential panel to study their problems and needs. She reminded him that in a recent Congressional report on mental health, “the retarded aren’t even mentioned.”

The resulting 1961 Presidential Panel on Mental Retardation, on which Shriver served as unpaid consultant, led to passage of the 1963 Mental Retardation Facilities and Community Mental Health Centers Construction Act. At the bill signing, President Kennedy acknowledged his sister’s significant contribution. He scooped up a handful of pens and gave them to her. “Here,” he said, “you give them out.” He realized Eunice knew better than he who had helped pass the legislation and deserved the recognition.

After her brother’s death, Shriver continued lobbying congressmen and senators to renew the law or include funding for the intellectually disabled in existing or new laws. A Kennedy Foundation executive told me, “She’d be brief, went to the point, and wrapped it up in 10 minutes. Then she’d tell me how Jack would handle it, as if Jack were here right now.”

(1936–) first wife of Sen. Ted Kennedy

Joan Kennedy

I couldn’t get an interview with her. She’d recently received a lot of negative press because she’d worn a silver minidress to an afternoon White House reception for Nixon’s inauguration. So I decided to interview around her. I asked the Kennedy press office to get me names and numbers of family and confidants. I interviewed her younger sister about her coping methods as a senator’s wife; a college roommate from Manhattanville College of the Sacred Heart, where she’d majored in music; a Kennedy cousin who’d campaigned with her during her husband’s immobilization from a plane crash; Arthur Fiedler, who led her in narrating Peter and the Wolf for a fundraiser; and other senators, congressmen, and their wives.

Eventually Joan relented and gave me the interviews. She wanted to know what other people had said about her.

My Good Housekeeping cover story on her came out a month after her husband’s car crash and accidental drowning of his passenger, Mary Jo Kopechne, on Chappaquiddick Island. On nearby Cape Cod, my parents, vacationing near the Kennedy compound, couldn’t find their daughter’s Kennedy cover story for three days.

(1928-2017) actress

Jeanne Moreau

I interviewed the French actress for the 1976 charter issue of Working Woman in Beverly Hills, at the home of her husband-to-be, director William Friedkin. She didn’t want questions about her work with preeminent New Wave directors such as Louis Malle, François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, or her recent directorial debut on her feature Lumière. Instead, she volunteered stories about growing up in Vichy, south of Paris, where her father owned a hotel and restaurant that were run by her mother, a former chorus girl who’d danced at the Folies Bergère, the famed Paris cabaret music hall.

“I was a tyrant and I didn’t like to eat,” Moreau recalled. She remembered telling her mother, “ ‘I will eat if you dance.’ To eat something else, I said, ‘I will eat if you sing.’ ” They were complicit in their fantasy that her mother was still a dancer and singer.

She denied that her first marriage to actor Jean-Louis Richard because of her pregnancy mirrored her mother’s. “I worked until the end of August,” she said. “My son was born the 28th of September. I got married on the 27th. I went back to work on the 5th of October [at the Comédie-Française]. When people expected me to act traditionally as a mother, I couldn’t.”

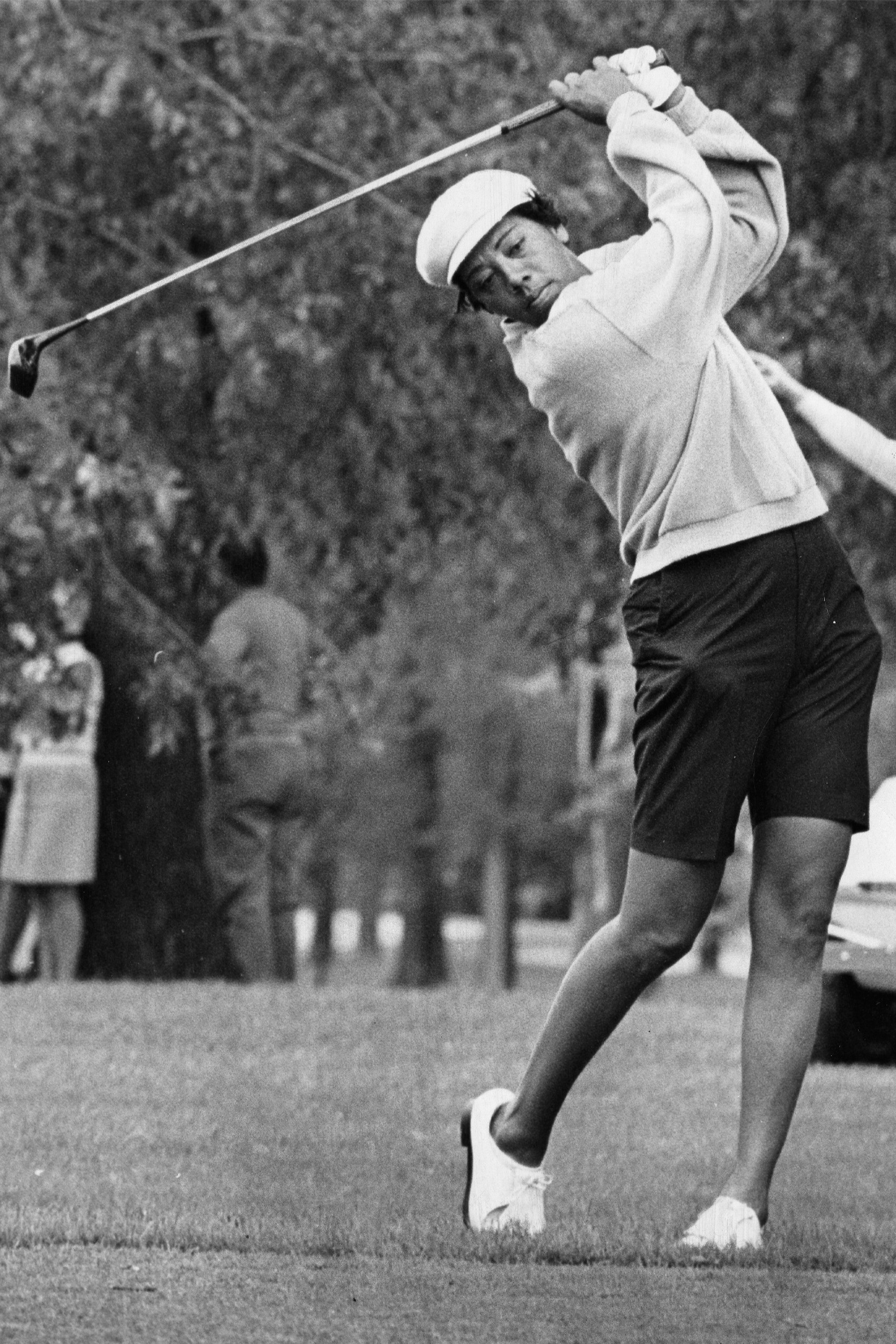

(1927-2003) first Black player to win a tennis Grand Slam (1956) and Wimbledon (1957)

Althea Gibson

I covered her first when she played in the LPGA—the first Black player to do so—at a season finale in Conroe, Texas. One night on the tour, I asked her for memories of her first Wimbledon. She said, “I took a shot of brandy before going on the court to ease cramps in my stomach. As I did before every game, I did warm-ups. I was really relaxed between sets. I drank a glass of hot tea that made me feel cooler. I sweated a great deal, but I was unaware of that and the crowds. I was oblivious to the bleachers till after. Then I saw and heard them and the Queen and the red carpet. And I curtsied though I hadn’t made or practiced one till then.”

Despite winning 11 Grand Slams, she told me, “I couldn’t get a position anywhere in this country as a professional teacher [in tennis]. I couldn’t make a livelihood through my game. It was a bitter pill to swallow. Golf was the most associated sport I’d encountered, so I thought I’d try making a living in golf.”

She had one good moneymaking year, in 1967, when she pulled in $8,000 (about $71,000 accounting for inflation). “Two friends sponsored me and I did my best.” Afterward, she paid the $250 for weekly entry fees, motels, meals, and gas out of her own pocket. She vowed, “I’m going to get it all back.”

Not so. Her late start at age 37 and tennis worked against her. Her lifetime earnings totaled about $25,000. But she was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame and the International Women’s Sports Hall of Fame, and she served as an inspiration for the Williams sisters.

(1897-1981) eight-time Oscar winner

Edith Head

The costume designer greeted me the first day on the set of Universal’s disaster film Airport ’77. She looked very much the schoolteacher she once was in her signature black horn-rimmed glasses, bangs, slicked back hair, and trademark plain beige pantsuit. Her image of authority had been created for her by her mentor Travis Banton, costume designer of the glamorous Hollywood Golden Age. By now, Head had done more than 1,000 films and dressed Paul Newman, Marlon Brando, Mae West, Grace Kelly, and Audrey Hepburn. She had learned the palette of directors John Huston and Alfred Hitchcock.

The tension on set was palpable. Olivia de Havilland had just flown in that weekend for fittings. Head had been working 12 to 14 hours per day. She sustained her energy by eating high-protein foods such as cheese, hardboiled eggs, and chocolate. She told me, “I believe in pampering yourself if you’re working very hard. I say, ‘Edith, you poor thing. I feel very sorry for you. Have another chocolate.’ ”

She credited her beautiful home and comfortable lifestyle to the shrewd money management and investments of her husband, two-time Academy Award-winning art director Wiard Ihnen. Most of Head’s salary went to taxes. She said, “I’ve always spent every cent on myself—books, objects d’art, or travel—because I’m extravagant.”

Growing up in a mining camp near Searchlight, Nevada, Head never sewed clothes for her dolls. “Everything I made was with safety pins,” she said.

This story was first published in the October issue of D Magazine with the headline, “A Life on Tape.” Write to [email protected]. Copyright © 2022 by Barbara L. Kevles. All rights reserved.