Day 1, Wednesday

4:15 PM

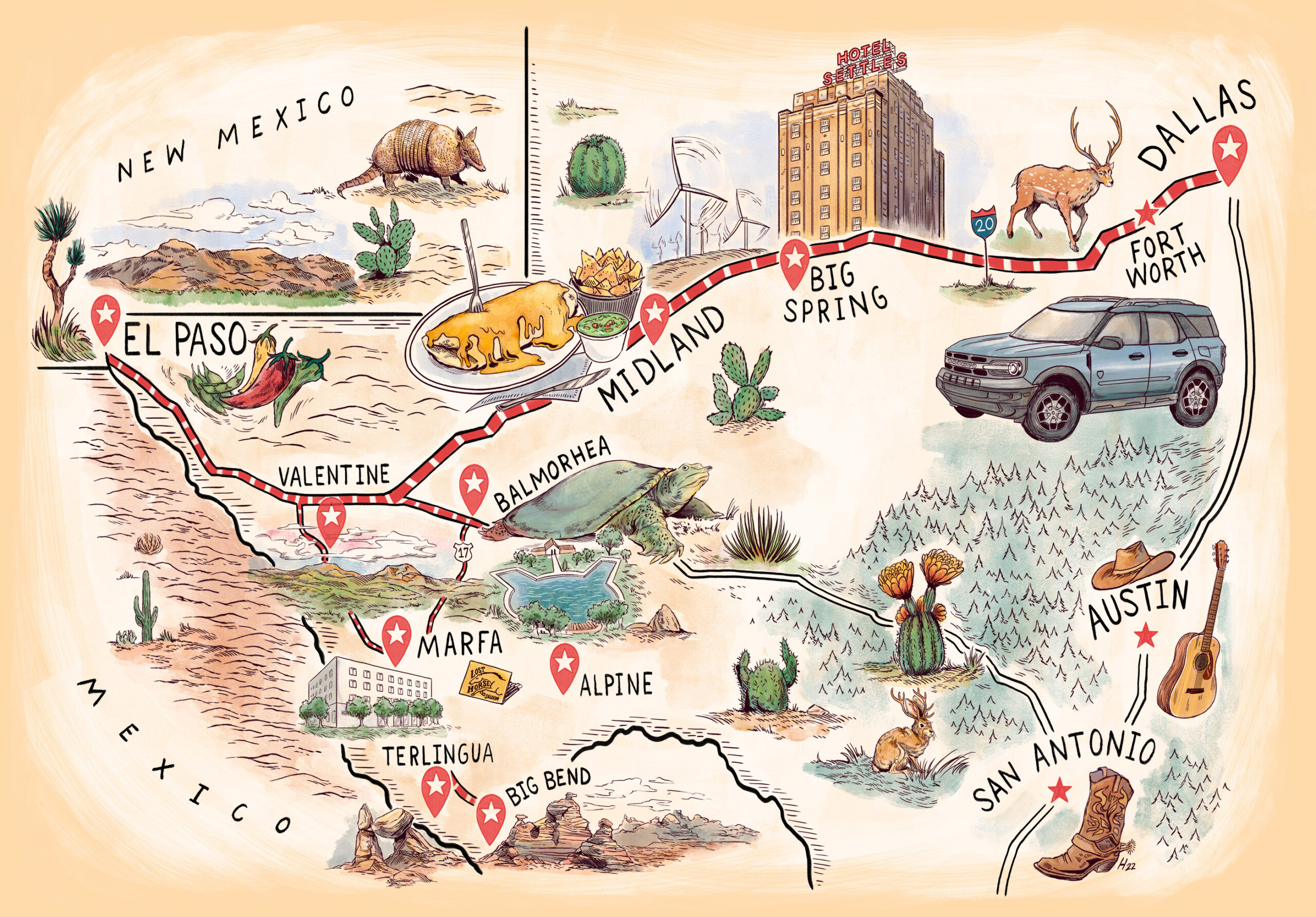

Fort Worth may be “Where the West Begins,” but the West can’t begin until you get through Arlington traffic. Fort Worth forgets to tell you that. Our travel plans require a little under 1,700 miles of driving over six days, which should work out to 26 hours. That amount of time and distance is difficult to conceptualize, so I pack six too many shirts, and my wife, Amber, brings along a plastic bag the size of a human thigh with bulk trail mix from Cox Market so we won’t starve on the open road. Or while sitting here at a standstill. I can picture Tom Landry, arms crossed and eyes narrowed, staring me down from under the fedora etched into I-30 because we left after 4 pm on a Wednesday. Leave earlier and avoid his judgment.

6:11 PM

The landscape begins to morph once you get west of Fort Worth, somewhere around Palo Pinto County along I-20. Hills sprout in the distance, the highway narrows, and it suddenly feels like we are going somewhere. Out of office, on vacation. But then, while driving through Eastland County, near Ranger, an axis deer moseys toward the road, not adjusting its gait. I hit the brakes hard at the same time she stops to graze alongside a berm. I hope this is the last time I see an animal large enough to take out a Ford Bronco (Sport) on asphalt for the next week.

8:33 PM

In late August, shortly before our trip, NASA released audio of a black hole for the first time. A galaxy cluster had so much gas around it that it allowed soundwaves to form instead of getting sucked up by the vacuum of space. It feels like a special moment, scientists finally recording the sound that we layfolk didn’t think existed. The black hole sounds like the cosmos eating itself, pure devastation, the literal end of the world. The doom metal of Sunn O))) playing in hell. Turns out, that’s what your tires sound like when you’re on I-20 about a dozen miles outside of Big Spring.

9:10 PM

At 15 stories, the only things taller in this part of Texas than the Hotel Settles are the wind turbines. The hotel is an Art Deco relic that was built in 1930, when the oil business in the Permian Basin was so good that it was difficult to see a future here without a hotel good enough for Elvis.

The past is all over East Third Street, where the hotel’s neon-red rooftop sign shines over the prairie. The street is so wide that it could comfortably hold at least another lane if someone would put some paint down. But at 9 on a Thursday night, there are no vehicles other than our Bronco. There’s bingo advertised on the left, the Tire Time tire shop on the right, and a perfectly preserved Gulf Station. Today, the Settles is a reprieve from oil derricks and those turbines, a flashback to when tiny Texas towns boomed and then went bust.

Big Spring wouldn’t have made our itinerary had Dallas taxman G. Brint Ryan not spent $31 million and six years renovating the Settles. It reopened in 2012. (There is a plaque with his face on it and an email address for comments, which is the first time I’ve ever seen an email address on a plaque. A message I sent went unanswered.) The hotel fell into disrepair in the early 1980s, after the Webb Air Force Base was shuttered. The city foreclosed on the property about a decade later but struggled to close a deal to bring it back to life. It became the realm of vandals. They smashed the windows and let in the elements. The lobby flooded because there was nothing to keep out the rain. Townsfolk wanted it torn down. Then-city manager Gary Fuqua told Texas Monthly in 2013 that “the Settles had become a monument to Big Spring’s failure.”

Ryan doesn’t hide the hotel’s recent history. In the lobby, to the right of the ornate wraparound staircase that leads to high-ceilinged ballrooms, you’ll find plenty of photos from the Settles’ heyday, when it hosted oil royalty and when 3rd Street was packed with Model Ts. But there are also framed images showing how bad it got. In one picture, the bombed-out lobby is nearly unrecognizable, the terrazzo floor smashed into pieces. Someone had spraypainted “The End Is Nigh” near where a giant painting of Ryan’s late mother now welcomes visitors. The decades of decay and the black-gold glory days are presented simply as part of the hotel’s story. Another photo depicts rooms that could have sustained tornado damage; Amber notices that Ryan kept the crown molding.

Those rooms are enormous and feel stately, which, for as low as $120 or so a night, is a bargain. We have the Settles Grill to ourselves. We cut into steakhouse-quality New York strips at a fraction of what you’d pay at Bob’s or Al Biernat’s, complete with garlicky mashed potatoes and springy green beans. We sink into the dark-blue booths and smile contentedly, happy to be off the road, surprised at how good our first meal is.

The old Settles Drug Store is now the Pharmacy Bar & Parlor, which tonight is manned by Seth and Elli. He mouths the words to the Metallica power ballad “Nothing Else Matters” while she stands at the cash register. Two men—one in his 60s, the other in his 30s—sit at the edge of the bar, nursing whiskeys in their Billy Joe Shaver best, all denim and accents. Haw’err y’awl? We chat up Seth and Ellie after Seth flips a fifth in the air like a West Texas Cocktail sequel. (I’ll let you imagine that he catches it.) They have ambitions to open their own bar soon.

“The hotel’s been real good for the town,” Seth says. “We wouldn’t be opening our own place without it.”

At last call, Seth invites us to a nearby cigar bar that’s in an old train car, but bed wins out. It is just an elevator ride away.

Day 2, Thursday

8:01 AM

Good news: driving on I-20 west of Big Spring does not sound like the cosmos imploding.

8:43 AM

The drive into Midland is dull and drab, rows of suburban rooftops and big-box retail bifurcated by a highway. But there is warmth in Oscar’s Super Burrito, whose pink walls are covered with posters from local high schools that have accumulated over the years. (Let’s go, 2002 Midland Christian Lady Mustangs!) The menu at Oscar’s is encyclopedic and will create a mild panic for the unprepared. If they have an ingredient in the back, they’ll put it in a burrito, and they’ll write that on the menu, and then you’ll get overwhelmed. The flour tortilla can barely fit on a plate, a fluffy, dusty cloud that comfortably holds a mix of—deep breath—bacon, sausage, ham, chorizo, egg, potato, beans, onions, tomato, jalapeño, and hashbrowns. (That’s the smothered burrito.) Or, you could be like Amber and get a pancake big enough to wear as a bucket hat.

10:10 AM

A tip: grip the steering wheel tight when you get out of Midland. We shove a case of Modelo in the backseat and pull back onto I-20, which has been taken over by 18-wheelers and box trucks. There are flatbeds packed with wire and water and construction materials and huge canisters of diesel fuel. The shoulder is littered with shredded tires and mangled bumpers, and, oh, someone ditched a car that’s missing its entire driver’s side panel. It’s like space junk rained down. Speaking of: there’s apparently a meteor crater museum in Odessa. We don’t stop.

It’s noisy here at Balmorhea, in the way that nature is noisy: there’s a chorus of crickets and an owl hooting somewhere in one of the dozens of trees that hang over the picnic tables.

12:15 PM

Balmorhea State Park is a salve, a somehow-not-a-mirage in the desert that appears when the Davis Mountains emerge in the distance. Balmorhea Lake is the largest spring-fed pool in the world, and its coral blue water is just about the only thing that can erase the preceding three hours of flat, barren oil land. The park comes courtesy of FDR’s Civilian Conservation Corps, which, in the 1930s, got to work building a couple bathhouses, a concession stand, and the San Solomon Spring Courts motel to accent the pool. It’s noisy here, in the way that nature is noisy: there’s a chorus of crickets and an owl hooting somewhere in one of the dozens of trees that hang over the picnic tables. (My wife, who is smarter than I am, tells me, “Owls aren’t only nocturnal, Matt.”)

Balmorhea is juiced by 15 million gallons of water that flow in each day from the San Solomon Spring, shuttled along fault lines and through porous limestone before being pumped into a manmade, 1.3-acre pool. The temperature stays somewhere around 73 degrees, and jumping off one of the state’s three best diving boards into 25-foot-deep water is a jolt.

Try to visit when kids are in school; there are only about a dozen people here on this Friday afternoon. There’s a turtle in the middle of the water, also enjoying not having to dodge children in floaties. Schools of guppy-size Pecos gambusia and Comanche Springs pupfish—both endangered because of the state’s vanishing natural springs—surround us like we’re chum. When we stand still too long, their nibbles feel like a pinch. The limestone floor is so slick that we slip and slide until we fully surrender, floating on our backs while catfish feed along the lakeside. It’s easy to melt into Balmorhea.

3:09 PM

We reach the Trans-Pecos in the days following what the National Weather Service terms a “moisture-rich monsoon fetch,” which, for our purposes, means as much as 5 inches of rain zapped all the brown from the Davis Mountains in less than a week. State Highway 17, the most direct route between Balmorhea State Park and Marfa, is a picturesque cruise through the nearly 3,000-acre state park that today is covered in rich, green vegetation. We got lucky. I don’t know how you time your trip to see it like this, but do give it a try—the summer monsoon usually comes between late June and September. Green or not, you can still marvel at the enormous basalt columns: rugged, vertical ridges that appear violently carved into the sides of the mountains. These were created nearly 40 million years ago as lava cooled. It’s unlike anything I’ve seen in Texas.

6:59 PM

We have dinner reservations at the James Beard-nominated Cochineal, whose tasting menu features herbs, greens, and vegetables from its own garden and nearby specialty farms. Game meat comes from ranches in Texas and New Mexico—whatever chef and proprietor Alexandra Gates can get her hands on that day. For our meal, the goat cheese halloumi comes from Marfa Maid Dairy down the block, the mushrooms from the Big Bend Fungi Company, and assorted vegetables from someone named Farmer Chris back in Fort Davis. Out of the six courses, the shrimp is the only ingredient that doesn’t come from Texas. Our favorite part of that dish—string beans that had been tossed in a fire—had been pulled from the restaurant’s own garden. Even the purslane, typically thought of as ground covering, came from the property. We dip the bitter herb in the remains of some chile oil after we inhale the house-baked heritage grain bread.

Marfa was first successful in the 1920s as a cattle town. The Army moved in before World War II and moved out when it ended. Giant was filmed here in 1955; the cast stayed in the Hotel Paisano, which still stands, ornate and resolute, on Highland. The art came with Donald Judd, the artist who became enamored with the horizon and the landscape and began scooping up properties in the early 1970s. (More on him tomorrow.) But the recent commercialization comes courtesy of the attorney and developer Tim Crowley, whose Crowley Theater has hosted local theater troupes but also the likes of Wallace Shawn and John Waters.

We stay in the Hotel Saint George, which Crowley opened in 2016, across from the Judd Foundation headquarters on Highland. It’s a hotel fit for arts patrons, the type of place that has a Gustav Mahler quote etched into the metal soap dispenser brackets.

Not that that’s a bad thing: like much of Marfa, you’re far from home but near your creature comforts. Planet Marfa could be the city’s answer to our Grapevine Bar, an outdoor watering hole with plenty of neon lights and more than a couple of cats. The Lost Horse Saloon is the West Texas dive of your dreams. The Marfa Spirit Co. transformed an old warehouse into a distillery with a bar and restaurant that sells its own sotol, which it produces in tandem with Mexican distillers.

Day 3, Friday

9:07 AM

The Chinati Foundation sits on 340 acres at the edge of Marfa, on what was formerly Fort D.A. Russell, an Army base that was decommissioned after WWII. Donald Judd began purchasing the property after becoming disillusioned with New York City and the art world in general. Tired of how museums commodified art and blundered its installation, he had the idea to create one of the few permanent, site-specific collections of art in the world. He was taken by the Chinati Mountains in the distance, how the vacant military buildings could house works that would help others experience the desert in a different way. (Judd’s insistence on working within existing structures is among the earliest examples of adaptive reuse.)

Alex, our tattooed, cowboy-hat-wearing docent, explains that Judd was fascinated by the contrast of order and chaos. How we cannot control the immediate world around us—seasons change, drought sucks the color from the flora, storms pass on the horizon, animals come and go—but we can frame it. Judd believed luxury was light and space, not objects, and viewing his work through that lens helps explain what Judd sought to deliver here, and why he chose Marfa.

Amber and I take the north tour, which includes works by Judd, the Ukrainian artist Ilya Kabakov, the light artist Dan Flavin, and a 2016 piece that the 94-year-old Robert Irwin considers his masterpiece. (Bring water and a ballcap. It takes us about four hours to walk.)

Two former artillery sheds now hold 100 aluminum boxes, each with the same specifications—72 inches long, 51 inches high, 41 inches wide—but with subtle design differences that create little mirages, where shadows and angles alter your perception. This is Judd’s 100 Untitled Works in Mill Aluminum, which was completed over 10 years with the help of artisans in Massachusetts, who followed the artist’s designs. But the world outside those boxes is just as important: Judd replaced garage doors with glass windows that present the desert as part of the piece. Your perception of the landscape changes with every cloud that covers the sun.

This experience can’t be replicated in a museum or a gallery; it only happens here, in this place, and each piece of art reminds you of that in different ways. Kabakov’s School No. 6 transforms an old military barracks into an abandoned Soviet-era schoolhouse, complete with little handwritten anecdotes from schoolchildren meant to challenge (again) your perception of what is real. Alex tells us that “even the dust” is part of the trip. Kabakov wanted Chinati to keep the entire structure open to the elements so that it disintegrates with time. They settled instead for letting the courtyard between the two structures stay wild and overgrown so nature—including snakes and, in one case, a mama bobcat—can encroach on what they’ve built, proving we cannot stop what is inevitable.

The final piece is Irwin’s Untitled (Dawn to Dusk), which took the place of an old Army hospital that was too damaged to hold what Irwin originally envisioned. The windows are higher than we’re used to, presenting a different view of the horizon. The two rooms are each bisected by tightly pulled scrim. The black fabric creates a feeling of dusk, and the light from the other half yanks you into a new day. The courtyard outside features a structure made of basalt from the Pacific Northwest. But it isn’t hard to see the sides of the Davis Mountains in it.

1:22 PM

The only “What Would Donald Judd Do” bumper sticker I see on this trip sits in a stack on a slash-shaped table at Wrong Marfa, the idiosyncratic art gallery and gift shop on Highland Street. Wrong is a pink-drenched joy, and not just because an employee’s fluffy dog, Ferdi, has chosen to scuttle at your feet. There’s jewelry from local artisans, prints by local artists and local photographers, ceramics by local ceramicists, and the only store-branded shirt I’ve ever bought. It says “WRONG” in blood red in the shop’s saloon-style typeface.

Every place we go in Marfa—restaurants, bars, shops, galleries—focuses its attention on West Texas and the creators who live here, at least as far as they can. Part of that might be necessity: the nearest large city is El Paso, damn near 200 miles northwest.

2:13 PM

The Château Wright Winery has dozens of rows of grapevines, an Airstream that sells sandwiches and burgers, a patio for obvious reasons, a couple buildings where the seasonal workers live, and, on our visit, a litter of nine kittens that are scurrying all over the concrete. A spotted gray one peels off from his siblings and jumps up on a table about 4 feet from ours. He considers the distance and leaps, sticking his paws into the metal holes in our table and pulling himself up before sliding off. (I help a little.) He’s a feline Ethan Hunt. This is Tofu, and he loves us. Or he loves our burgers. Whatever.

Get the tasting; it’s free if you follow it up with a glass. We picked the Griffin Red, which is made from cinsault grapes. Traditionally found in France but perfectly suited for these West Texas climes, the varietal produces a wine so effervescent it’ll trick you into thinking it’s carbonated. It’s the perfect Chinati chaser, and, if you’re heading to Terlingua from Marfa, the winery is a 40-minute detour that’s worth the time.

We stare out at the grapevines and the Davis Mountains for an hour or so and order a few bottles to go. Tofu stays put.

4:01 PM

The largest International Dark Sky Preserve in the world extends about 400 miles south from the Davis Mountains and the McDonald Observatory to the city of Ocampo in Coahuila, Mexico. At night, the math works out to 15,000 square miles of darkness, although, looking east from the conservatory, you can still make out flickering lights from drilling rigs and gas flares in the Permian Basin.

Down in Terlingua, about two hours south of Marfa and dead in the middle of the preserve, all disturbances disappear. The sun sets beyond the Chisos Mountains, and the sky turns ink-black, only lit by pops of shooting stars, Lite-Brite constellations, and the speckled glow of the Milky Way.

We check in for two nights at Willow House, a newish development at the foot of the Chisos that features a dozen concrete-cube casitas and a main house with a kitchen and living area that’s shared among visitors. (You get your own cubby in the fridge.) The property is arranged so visitors can take in everything around it. Each unit features wide windows pointed at where the sun peeks out from behind the range in the mornings. Through the frame you’ll see a pastel-pink sky that deepens into a fiery orange.

The woman behind it all is Lauren Werner, an SMU grad from Southern California who started looking for land to purchase during a solo road trip to neighboring Big Bend National Park. She found a little under 300 acres of land, dotted with spindly ocotillo and stumps of agave, boasting unobstructed views of the Chisos and Santa Elena Canyon, an impressive portal along the Rio Grande that features towering walls up to 1,500 feet tall.

Marfa is slow, but we still felt hurried—dinner reservations, subjective opening and closing hours, ticketed art tours. All those manufactured pressures vanish in Terlingua, where we finally feel like we have reached the end of the road. We set our things down in the lavender-scented casita No. 7 and wander out into the desert. Storm clouds hover over a distant mountain and blast down a vertical wall of rain that looks more like a painting than something we are watching in real time. Werner cites Georgia O’Keeffe, not Judd, as an influence. She chose to let raw nature speak for itself, chaos and all.

Werner knows the best way to highlight these surroundings is for the property to stay out of the way but still be there when you want it, so there’s room to roam at Willow House. She’s arranged a seating area and fire pit a couple hundred feet out. Just beyond, you’ll find a swinging daybed that makes it easy to lie on your back and see the Milky Way above, looking like spilled salt on a black tablecloth.

8:33 PM

The closest thing to a city center is the Terlingua Ghost Town, about 3 miles away, where we find the ruins of the Chisos Mining Company, a very-much-worth visiting cemetery, the old St. Agnes Church, and a couple bars and restaurants. Locals wander to the porch between the Terlingua Trading Company and the Starlight Theatre Restaurant with their own beer at sundown, passing a guitar and avoiding a bar tab. The Starlight—a former movie theater from the ’30s that earned its name because, for years, it lacked a roof—offers the sort of frontier food you’ll crave after a day spent hiking.

But we lose track of time, and the Starlight’s kitchen is closed when we arrive. Across the street is the High Sierra, where Mike Kasper holds court on a small stage with a drummer and another guitarist, a guy named Randy de la Fuente, whose day job is as a river guide. (“Come back and I’ll show you shit you ain’t never seen,” he tells us; you can take him up on that by emailing him at [email protected].) Kasper, with white hair that hangs just below his shoulders, goes by the stage name Dr. Fun. He’s lived near Big Bend for almost 40 years in a solar-powered home. He calls this part of the world “the real Texas,” the type of place you used to have to work to get to, the one that’s still remote despite all the money and recent interest.

Terlingua is a former mining town that’s attracted creatives and river guides and other sorts of ramblers for decades, long after influenza put a lot of the miners in the cemetery. It’s where North Texans Frank X. Tolbert, Carroll Shelby, and David Witts helped start the Terlingua Chili Cookoff in 1967, which attracts 10,000 people every first weekend of November. (It was November 2–5 this year.) On our visit, Terlingua is, well, a ghost town, populated by the few people who live here, sprinkled with tourists like us.

Dr. Fun makes light jabs as we look at our phones. He takes requests from the dozen or so folks in the room while we eat our enchiladas and nurse Lone Stars. He plays John Mellencamp’s “Pink Houses” Bob Seger’s “Against the Wind,” and a drawn-out, surprisingly emotional rendition of Neil Young’s “Rockin’ in the Free World.” A couple in their early 40s dance to Chris Isaak’s “Wicked Game” for their anniversary.

I give Kasper $20 after the show and ask his thoughts about all the recent development that’s come to the desert. The out-of-towners who buy property and make this a part of their lives—the High Sierra was recently purchased by a Southlake man named Steve, whose request for the night was Mellencamp’s “Jack and Diane”—don’t bother him, he says. It’s the quick-build Airbnbs, scooped up by investors far away who don’t show up again after scouting locations.

Dr. Fun leaves us with an anecdote. He once gave a river tour to a Scottish man whose name he can’t remember in a year he can’t recall, but that guy told him something profoundly simple: “Our paths may never cross again, but we’ll always have these memories.”

And with that, we drive back out into the inky night.

Day 4, Saturday

7:47 AM

Terlingua is between two of the world’s largest public parks: Big Bend National Park to the east and Big Bend Ranch State Park to the west. The more popular hikes are east. There’s the Lost Mine Trail, a 5-mile out-and-back with a steady incline that delivers immense views of the Chisos range, and the Window Trail, a 5-or-so miler that tracks along the basin of a canyon and delivers a vantage through the mountains that evokes its name. The latter trail is closed because of black bear activity. So we go west.

Out past Lajitas—beyond Kelcy Warren’s golf resort and the beer-drinking goat mayor that’s kept in a tall cage—FM Rd. 170 runs more than 30 miles along the Rio Grande and through two truly epic mountain ranges. The road is a mix of blind curves, steep canyons, and abrupt drops. For much of it, El Camino del Rio tiptoes just above the cliff faces. It takes about two hours to make it to the interior of the park from Terlingua, but it’s where you’ll find the remnants of the cowboys and miners and Native Americans who were here well before River Road got paved in 1961. But do not even attempt to get here without four-wheel drive.

9:22 AM

The good news is there’s plenty to see along FM Rd. 170.

The Rio Grande is flowing, powered by the recent rains. (We don’t get in, but Colorado Canyon is the easiest river canyon to access; expect Class II–III rapids and an 11-mile trip downstream to Lajitas from the Rancherias River access point.) We head to the Closed Canyon Trail, a slot ravine that leads you about a mile through a mountain. The ravine, too, has taken on some rain. We turn around once we meet a 2-foot-deep puddle, being the city cowards that we are.

But even stopping in that canyon is worth it. The temperature drops 10 or so degrees, and it’s suddenly eerily quiet. There are plenty of times when we feel alone in West Texas, but there is nothing like standing still in a canyon and marveling at what’s around you. We see only one other couple our entire time here.

Marfa Lights

Take a walk to Do Your Thing Coffee in the morning, stock up on organic goods at The Get Go, and grab a wood-fired zucchini and olive tapenade white pie at Para Llevar to consume in the courtyard. It’s all familiar but presented and delivered in ways you’ll only find here, by the people who have made this place their home and want to share it.

Do Your Thing Coffee, 201 E. Dallas St. | 432-701-0501

The Get Go, 208 S. Dean St. | 432-729-3335

Para Llevar, 203 E. San Antonio St., Marfa.

10:08 AM

A few miles west, another short trail is marked by an assortment of hoodoos. These ancient geologic formations look like alien mushrooms, the result of thousands of years of wind and water erosion. They all sit on what’s basically a plateau above the Rio Grande corridor, where you can watch pink-and-blue kayaks push through the water below. A spur on the trail shoots you up to a lookout where you can watch the river as it flows back east.

If you want to see more of Big Bend, the state park is a better fit. There is an assortment of short hikes along the river road that reveal different pieces of the valley and the mountain ranges. Nothing we do is particularly strenuous, but the sights are astounding: canyon walls up close, valleys that stretch for miles, the joy and stress of driving a narrow highway road through a mountain range.

12:35 PM

The national park offers a different sense of scale. The many overlooks deliver expansive views of the entire Chisos range. (Don’t miss Sotol Vista.) But after driving through the state park, where it often felt like the road had been carved into the literal side of a mountain, navigating the national park is a breeze. There aren’t nearly as many cliffs to negotiate, and taking my eyes off the road for a second or two (sorry, Amber!) to admire the view doesn’t feel like as much of a risk.

2:22 PM

When we pull back into Terlingua, DB’s Rustic Iron BBQ is at the edge of the Ghost Town, about five minutes after our cell service kicks back in. We order a fistful of smoky pulled pork, thick and silky slices of fatty brisket, piquant sausage, and a few whole pickled jalapeños. Turns out there’s great barbecue at the edge of the world, and we take down the tray sipping on $1 PBRs while a norteño mix blares through the open garage door.

4:09 PM

We decide that Dr. Fun’s anecdote had some wisdom: we keep our memories and stay put in Willow House for the night. We pick up a couple of steaks and some vegetables from Cottonwood General Store—and dodge three sprinting roadrunners, which are small and quick enough to avoid tires—and try out the Argentinian-style grill near the shared house. Everyone has access to this beast. You place smoldering coals on the long flat-top and grill your dinner on a grate.

We’ve made friends with Ode and her partner, Iro, both of whom migrated to Texas from Cuba. First to Arlington and then to Terlingua. (Again: does the West begin in Arlington?) The two live on the property and help maintain it. Molly, who does marketing work for Willow House, and her boyfriend, Colton, are here, too, sipping ranch waters and sharing local news. Apparently a plumber has just moved to town.

8:27 PM

As night falls, seven Austinites, who were staying in some of the other casitas, pull back in from hiking. We all hang out in the living area, melting into the leather safari chairs, sharing wine from one of the bottles we brought from Château Wright and learning a bit about each other. They are here for an annual entrepreneur retreat. One of the Central Texans, Jay, came here years ago for the chili festival and hasn’t stopped coming back.

We spend the end of the night under the cosmos, listening to Jerry Jeff Walker and Four Tet on a Bluetooth speaker, occasionally feeding the fire with bone-dry pieces of dead ocotillo branches. It’s a perfect way to end our time here, with strangers who’ve become friends, if only for a weekend, all sharing a sky that will probably take years to get back to.

Day 5, Sunday

11:02 AM

As we head north, driving back through Marfa, we pass a collection of billboards painted by muralist John Cerney. James Dean and Elizabeth Taylor rise high out of the earth, the Giant mansion in the background, forming an enormous tribute to the film off State Highway 90. Nobody’s lined up to see it, especially not like they are farther up the road at the Prada Marfa installation in Valentine.

You know what it is: Berlin artists Elmgreen & Dragset were commissioned by Ballroom Marfa to build a fake Prada storefront 20 or so miles out of town, which would over time be worn down by the elements. In theory, it’s a commentary on consumerism, but in practice it’s a magnet for Instagrams—and TikToks, I guess. There’s a four-car-deep line of influencers waiting to hop out and get their own shots. They’re waiting on a couple—he, dressed all in black and wearing a pair of Nike Blazers, is pointing his iPhone at her, who’s in cowboy boots and a black dress with a wavy scarf—to finish posing and move off.

In between the Giant tribute and Prada Marfa is a more resonant marker, placed by the Texas Historical Commission in 2019 after advocates pushed for more than two decades for the state to recognize the Porvenir massacre. During the Mexican Revolution, in 1918, Texas Rangers, Army soldiers, and local ranchers marched into a peaceful Mexican American community and massacred 15 boys and men, who are named on the marker. The survivors fled, and what was once a town of 140 is now commemorated only by this bronze plaque.

There wasn’t a line there, either.

5:15 PM

For the purposes of this trip, El Paso is merely a stopover, unfortunately. It’s a beautiful city, full of history and architecture, but it’s shut down on Sundays. Or at least the downtown is.

Which is fine. We’re zonked. We check in at the historic Hotel Paso del Norte, drop our bags in the room, and head to the 10th-floor rooftop pool, where we can see the aging towers of downtown as well as the line at the border with Juarez. From our room, the lights of Juarez look like fireflies.

We’ve had enough time in a car that the only thing appealing outside the hotel is a walk. Elemi and Taconeta, both newish taquerias that nixtamalize their own corn, are both closed until Tuesday. An El Paso friend of mine spoke highly of L&J Cafe, a Tex-Mex staple that opened in 1927. But, again, that would require getting back behind the wheel. His other suggestion is The Tap, a dive bar with surprisingly great food, but its kitchen closes early on Sundays.

We wind up staying put in the Paso del Norte, which opened in 1912 and got a serious renovation between 2016 and 2020. The bar, which is framed by a 25-foot Tiffany-style stained glass dome and enormous arched windows, is the centerpiece. Dinner at the hotel restaurant, Sabor, was fine—but it’s something you can skip if you’re up for leaving the hotel.

For dessert, we collapse into bed.

Day 6, Monday

10:04 AM

We wander into downtown after checkout. Martha’s Cafe is up the block, which looks more like a Dallas Cowboys memorabilia store than a diner. So we choose The Tap, whose kitchen is already pumping out nachos. Mariana is behind the bar; she says she’s worked here 29 years. An older man named Dominique nurses a beer and a shot and occasionally belts out “Stand by Your Man,” which Mariana turns into a duet.

“These are my bambinos,” she says, waving her hand to the half-dozen or so folks lining the bar. “They’re my heart. I pick up groceries for them.”

That sort of sentiment will make you feel less bad about being at a bar first thing on a Monday morning. So, too, does the salsa, a fiery mix of chile de árbol, jalapeño, onion, and garlic. The chips are house-made, and the nachos are the best I’ve eaten.

11:47 AM

The drive to Carlsbad takes us through the Guadalupe Mountains, an enormous, ominous range that features the highest point in Texas (Guadalupe Peak, 8,751 feet). It’s probably smarter to chop these trips up. Guadalupe Mountains National Park is just as rich with hikes and views as Big Bend, and then you won’t have to rush through El Paso. Live and learn.

We are destined for the Big Room at Carlsbad Caverns, the largest cave chamber in North America. It’s an easy 1.25-mile hike down the Natural Entrance Trail and another 1.25-mile hike back out. (You can also take an elevator straight to the Big Room.) It’s a surreal experience down here, 750 feet underground, with stalactites and stalagmites that look like everything from hanging resin to a walrus to a demon with a mouthful of knives for teeth.

6:36 PM

We stay the night in Carlsbad, at the supposedly haunted Trinity Hotel & Restaurant. Built in 1892, it was redeveloped by the father-and-son team of Dale and Derek Balzano in 2007. They also own a nearby vineyard, and they stock the wine list with their own vintages.

There isn’t much in Carlsbad—at a population of about 30,000 people, it’s smaller than even Waxahachie—but you could do a lot worse than the Trinity. Tall ceilings, tall windows, a rich history, and comfortable beds. Amber was in the restroom in the middle of the night when the sink turned on by itself.

I took it as a sign that it was time to get home.

This story originally ran in the November issue of D Magazine with the headline, “West Texas Waltz.” Write to [email protected].

Get the TravelClub Newsletter

Author