From November 2022

You have to be looking for Don’s Photo Equipment to find it. Sandwiched between an auto body shop and an audiovisual repair store on a desolate stretch of Irving Boulevard, the storefront is fairly unremarkable, with simple signage and bars on the windows. There is no indication of the rabbit hole you’re about to dive into once you open the door.

I visit Don’s for the first time on a Tuesday morning in June, arriving early to have a chance to chat with the owner, Todd Puckett, before the store opens at noon. I am greeted by boxes and boxes of equipment that most people haven’t seen or thought of since at least the mid-’90s. A small path is carved out from the front door to the back of the shop, where I find Todd at the customer counter. Behind it is an almost floor-to-ceiling cabinet filled with film. Real, honest-to-goodness camera film you used to buy in bulk for your high school trips and family vacations.

But there is so much more than that here. Did you know there is actual 8×10 film, which is only to be used with an 8×10 camera? Neither did I, but Todd’s got it. Are you interested in a Polaroid like the one your dad had in 1982? He’s got that, too. Maybe you’re after an old Super 8 motion-picture camera like the one your grandparents used to capture holiday gatherings before camcorders were introduced. Todd gets them in—along with the 8 mm film they use—though those tend to sell as soon as they arrive at the store.

I don’t know what I want. The truth is, I don’t know much about photography. Aside from taking a class in high school and dating a photographer in college, I’m a novice at best. But that makes me a perfect candidate to be a patron of Don’s.

“We are really a place for amateur photographers, traveling photographers, wedding photographers—anyone who loves analog photography,” Todd says. “We don’t want to be the only game in town, and we aren’t, but we are the only exclusively analog storefront and have one of the most diverse stocks of film in a five-state area.”

Given that small retailers have taken a beating during the COVID years, one might assume there is very little foot traffic. In my hour and a half at the store, however, no less than 10 customers come in for an assortment of needs. Some are dropping off film because Don’s serves as the storefront for Lone Star Darkroom, one of only a handful of developers in town for analog photography. Others are looking for obscure parts for their cameras. George Keaton, who runs Remembering Black Dallas, a nonprofit preserving African American culture and history in the city, stops by to pick up one of Todd’s older cameras to use as a prop in a stage production his organization is hosting.

All the while, the store phone—Todd’s OG flip phone—rings almost nonstop.

“Is it always like this?” I ask.

He shrugs and smiles. “It can be, yeah.”

A pair of 20-something women walk in. One is carrying a point-and-shoot camera. As she approaches the counter, Todd knowingly grabs an envelope for film drop-off and begins to explain she just needs to fill out the top part. When he hands her the envelope, she stares at it. Then she looks at her camera.

“Can you help me?” she sheepishly asks.

“With what?” Todd says.

“I bought this on eBay and my mom loaded the film for me. I don’t know what I’m supposed to do with it now,” she says.

“Do you mind if I ask how old you are?” I interject.

“27!” she says proudly.

Quick mental math tells me she was born as the death knell of the point-and-shoot camera began to toll, and while some of her earliest memories might have been captured on film, this young woman’s life has been largely digital, making the apparatus she’s holding a novelty.

Todd graciously walks her through how to wind the film in a camera, and then he takes it out and plops it into the envelope to be sent away. She and her friend happily leave, mesmerized as they go by the vintage excess around them.

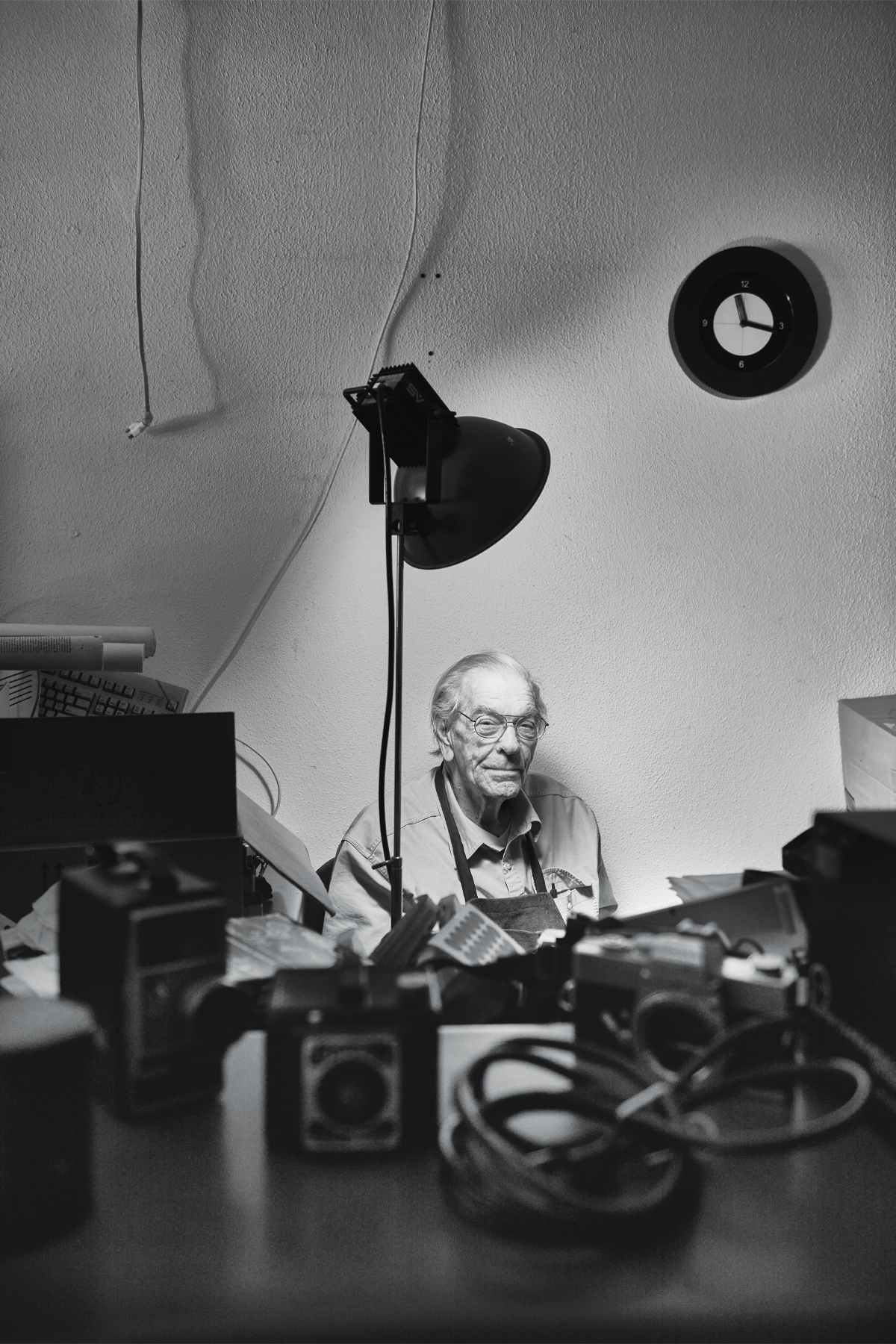

Todd’s father and the store’s namesake, Don Puckett, was born on Halloween, approximately 84 years ago, in Hooks, Texas, home to the artillery responsible for 70 percent of the bullets fired in World War II, as well as Heisman Trophy winner and former Detroit Lions running back Billy Sims. Largely self-taught, Don started shooting in the fifth grade on a Kodak Brownie but by high school used an Argus C3. His success as a photographer, Todd says, is due to his engineering mind. “Photography is just mechanics: how do things work together? Dad was always good at taking things apart and putting them back.”

He’s still good at that. Don is retired, but he comes into the shop daily, tinkering at a desk by the front door. Within the local photography community, he is lovingly known as a Polaroid Frankenstein for his skill at perfecting the use of Polaroid technology. Beginning in the 1970s, Don would use an amalgam of parts from different models to create the “perfect” Polaroid. According to Todd, he has made hundreds over the past decades. Many of the chop-shopped cameras ended up on movie sets to shoot continuity photos, precisely documenting the position of things between takes to ensure it all matches from scene to scene. His other specialized devices were used by party photographers, who would often sell them to subjects who were taken with the instant photos they received on the spot.

For more than 50 years, Don worked as a professional photographer. He was primarily commissioned for commercial work and portraiture, but he also collected (some might say hoarded) photography supplies and equipment, hosted trade shows, and even ran a few photography competitions throughout the Southwest.

Don and his wife, Betty, had only one child, Todd, who was born in Dallas in a year he won’t disclose. Though not a professional photographer himself, Todd learned by growing up around his father’s work.

“I kind of became fascinated with taking pictures of my friends when I was around 5,” Todd says. “My mom has a great picture of me with my Brownie camera, sitting on Dad’s green truck, taking pictures.”

Todd spent lots of time with his dad, driving around in that green pickup going on shoots. He upgraded to a Nikon by high school, and, though he’s mostly a hobbyist, he did take a photography class while getting his B.A. at SMU, sometime in the ’80s. He worked in marketing and on political campaigns before his professional career eventually led him back to his father.

The most definitive date Todd would share was 1997. That was the year he found himself at a career crossroads and his dad was ready to shift his focus. “It’s the principle of the three S’s—studio, storage, store,” Todd says about the genesis of their storefront. On the cusp of retirement, Don needed somewhere to put the stash of goods he had amassed throughout his lifetime, which was enough to fill multiple studios three times over. Thus storage. And, finally, store.

A great deal of Todd’s business comes from students. Many schools and universities are still teaching film-based photography, and he’s one of the only local resources who can provide the necessary equipment. Which isn’t always easy.

“If I could just appeal to everyone to not throw away their cameras—I need them for the next generation of analog shooters,” Todd says. “So many people throw their cameras away. I am lucky in that I have people give them to the store for students, but that happens less and less. Too many people do not believe film is still being made, so they think they have no use for their old cameras.”

It’s difficult to believe Todd has trouble sourcing product to sell when you are in the store. Shelves overflow with film projectors used to show reels in 10th-grade biology, camcorders of all vintages, and overhead projectors. Of the many cameras, some have been used as props in big-ticket productions. The biggest, 2001’s Ali, directed by Michael Mann and starring Will Smith as the boxing legend, featured an 8mm camera purchased here. He says the most expensive sale he’s ever rung up was a lot consisting of a couple dozen Nikon 35 mm cameras and lenses—most still in their original boxes-—that went for $6,000.

On another visit, Todd shows me an RB Graflex Series B camera made sometime between 1923 and 1951. It’s massive by today’s standards and feels older than it is because it has a chimneylike curtain that extends out the top, making the photographer resemble someone shooting at a saloon in the Wild West.

He also has—or he did when I was there—one of the very first zoom lenses made. And somewhere there is a handmade Sun lens, which is unique and rare and, like so many things, hidden somewhere under one of the piles spread throughout the store. “It’s the one thing that motivates me to clean,” he says.

In addition to the fun stuff, Todd also stocks a robust assortment of developing agents. Photography is largely chemical, requiring precise measurements and specific conditions to effectively process and develop film.

And yet, despite a store that seems to hold your every analog need, the supply is tenuous at best. Some of this can be traced to what Todd ominously refers to as the Great Analog Crash of 2003. That is when digital photography outpaced analog as the dominant medium. The cherished cardstock envelopes of freshly developed snapshots disappeared, replaced first by memory cards and eventually by phones with endless storage capacity.

Beginning in 2011, however, a film renaissance began. Todd says it was led by an unlikely character—everyone’s favorite flannel-loving, vinyl-collecting, mustache-wearing film dealer.

“ ‘If you see a hipster, give them a hug.’ That’s what Mike Bain says, and he’s right,” Todd says with a chuckle.

For 34 years, Bain, the former national representative for Ilford Photo, has lived in Dallas. Ilford is one of the oldest and most well-respected manufacturers of analog black-and-white film. Now known as Harman Technology, it is sort of the British counterpart to Kodak. Those companies remain two of the biggest players in the industry, and while they do still make rolls of film, the volume is significantly smaller than it was 20 years ago. To illustrate the point, when Bain began repping film in the United States in the 1980s, there was more than 100 Ilford staff members dedicated to North America. When he retired earlier this year, he was the only representative for all of North and South America.

When I reach him later, Bain says Todd was especially passionate about film even during the lean years. He credits Todd and his shop for doing their part to keep the analog community alive and thriving. When I tell him what Todd told me about the rebirth of film, Bain says, “I don’t want to disparage hipsters. I probably said something like, ‘We owe it to the younger generation.’ ”

The younger generation is learning the value of having something tangible. Todd tells me the story of a woman who came into his shop.

She told him that one Saturday afternoon, her eldest daughter had discovered a shoebox in her mom’s closet filled with her baby pictures. She and her little sister, who is six years younger, pored over each image, the younger one squealing with delight at how silly her big sister looked as a baby. Careful not to get fingerprints on the images, the girls took turns holding the photos, placing them gingerly back in the box as they moved through the collection.

“Mom! Where’s my shoebox?” the younger girl asked.

“You don’t have a shoebox—you’re a digital baby!” her mother replied.

As a mother of two young boys, this hit home. Both my sons are decidedly digital babies. Born in 2016 and 2019, their entire lives are on my phone. Not in an album. Not framed. Not in a Central Market paper bag lovingly placed in the hall closet with easy access. In my iPhone. As I think about this, I immediately begin wondering if I even have an actual camera in my house anymore. When was the last time I used one?

As this is running through my head, Todd seems to read my mind. “We have this cool Ilford point-and-shoot right here,” he says. It looks like a disposable camera, and it is in a box with illustrations reminiscent of the late singer and artist Daniel Johnston’s childlike drawings. It’s preloaded with a roll of Ilford film—ready to go.

“How much?” I ask with the guilty desperation only a parent can feel when they realize their children’s lives are solely stored inside an Apple product.

“Forty bucks—it’s a good deal,” Todd says.

Sold. I throw my debit card his way and stuff the camera in my bag, plotting when and how I’ll use it. Because that’s the weird thing about film—it feels special. There are a finite number of shots you get on a roll, so you have to be selective about what you document. Think about it for a second: in a world where you can take hundreds of digital images in mere minutes, no moment feels terribly sacred. It’s all editable. Ultimately, even real images lack authenticity, because you’ve picked the very best shot out of 15. Everyone’s arms are popped, eyes are open, hair looks good. Your children are all looking at the camera. No one’s making a funny face. It’s perfect.

How dull.

Unaware of the personal crisis I’m going through, Todd continues to talk about the camera I’ve just purchased.

“Daniel and Sarah did this,” he says. He is talking about Daniel Driensky and Sarah Reyes, the talented duo behind the creative agency Exploredinary. “Daniel draws—it’s his artwork on the box. You should meet them. They do documentaries and take pictures. They know Jason Lee,” Todd adds, referring to the skateboarder, actor, and photographer who used to live in Denton.

This is why people come to Don’s Photo Equipment; you don’t get this online. You can’t. Todd will gladly sell you a camera or roll of film or all the chemicals you could ever need to develop cherished images, but he’s really more interested in getting you excited about photography and ensuring the analog community in Dallas thrives. He celebrates his clients’ successes. He connects people.

Farther down the rabbit hole I go.

After my first visit to Don’s, I cold call Driensky and Reyes. Partners in business and life, they cofounded Exploredinary in 2015. As the name implies, they explore the ordinary and reveal the beauty in everything, especially the mundane. Their work—a mix of filmmaking, photography, and art— is nationally and internationally celebrated, featured on PBS and in the Wall Street Journal, Popular Science, and Playboy, as well as displayed at Le Salon des Arts in London and Paris.

I meet the pair for coffee at Halcyon on Lower Greenville on a 103-degree day in July. Daniel and Sarah also know Mike Bain. Oddly enough, they met in L.A. at a showing of one of Exploredinary’s films. They have since collaborated on six short films, including The American Photo Roadtrip, starring Lee. Daniel and Sarah have a deep love for analog photography and have created several films celebrating the art form, most notably one called Analog People, which explores several types of handmade photography, and another that gives the viewer a behind-the-scenes look at the Ilford factory in England. They’ve just released a series of new films focused on darkroom printing.

“The analog community in Dallas is very tight-knit,” they tell me. “It’s funny because we use digital technology to share analog stories and images.”

Where Todd is very much “give me analog or give me death,” Daniel and Sarah are excited by the benefits of all different forms of photography and film. For example, they’ll take digital images to perfect an image before shooting with film. Or they’ll share images taken with analog processes digitally. But when it comes to printing, they are very passionate about being in a darkroom.

After our first meeting, they invite me to join them at Photographique, a family-owned shop specializing in photographic restoration since 1982, located in Deep Ellum. The dark room is available for local photographers to rent, and Daniel and Sarah have reserved it to develop images for a current project. I haven’t been in a darkroom since 1997, and that was a closet in my high school journalism classroom.

“The analog process is multisensory,” Sarah says. “It involves smell, touch, sound. There is an incredibly powerful connection to the image established by these tactile processes.”

To hear her describe how light goes through different chemicals to emblazon an image on a page coated in silver gelatin is more like alchemy than chemistry. Or magic. Magic, when done correctly, creates images with the ability to last hundreds of years.

“We just don’t know what the longevity of a digital print will be,” Sarah says. “A photo is your history, something to look back on.”

The first time I met Todd, he told me, “A negative proves something happened.” You want that proof to last, never changed or altered, a backup to your mind’s hard drive of memories.

I spend an hour with Daniel and Sarah in the darkroom, watching as images came to life in real time, though they’d been taken weeks before. Magic.

Inspired to be part of the analog revolution, I decide to follow Daniel and Sarah’s advice: “Take your camera everywhere.”

Its maiden voyage is our family’s summer vacation. We begin in San Francisco and then take our 3- and 5-year-old sons on a drive down the Pacific Coast Highway to L.A. We stop midway down the state to spend the night, and then we get ice cream on the Santa Monica Pier late in the afternoon on the fourth day of our trip. But I don’t take photos of any of that.

I have saved the camera for Disneyland.

Even though I know I have 36 shots and can buy more film, I feel like I have to wait for our two days at the park. Once there, though, I realize maybe I should have gotten in a bit of practice beforehand. I struggle with the camera at first. For one thing, I have to constantly remind myself to actually use it. When I do, I find that the viewfinder is not generous. I’ve forgotten how hard you have to work to frame a shot on a point-and-shoot. You have to stand on benches, crouch to the ground, raise your arm high above your head and tilt the camera, praying it captures what you want. You can’t check your work. This is especially frustrating to children accustomed to looking through pictures on my phone like it’s their job.

The boys love the novelty of the point-and-shoot. Teddy, my oldest, who is trigger-happy with an iPhone and known to take rapid-fire images of our living room television, is especially enthralled. Not only is he excited to take pictures, he is willing to smile for the camera as well—a feat not accomplished in months with an iPhone. It takes a little while to convince the boys the camera is really taking pictures, since they can’t see anything in real time. Mercifully, they forget about it and stop asking to open the back and “check.”

I recall returning from trips in my childhood and waiting with Christmaslike anticipation to get the pictures back. Sometimes, if we were especially jazzed about seeing them, we’d rush the order. And order doubles. But we’ve been home for more than a month when I realize I haven’t developed the film. (I blame the lapse on the fact that we’d taken companion shots on our phones.) I am fairly impressed with myself that I remember how to wind the film for drop-off. I leave it at Don’s and ask to get it rushed. That means a week in today’s world.

A nice twist of modern technology allows you to have your analog images developed and then scanned, so you can preview your pictures before picking them up. They look super cool and grainy, because they are. I am especially eager to see how some pictures from our first night in the Magic Kingdom have turned out. Somewhere in the middle of Tomorrowland, my husband and I had one of those rare moments of parenthood that looks like what you imagined parenting would look like. We were watching fireworks, our boys wearing their mouse ears that look like R2-D2 (because Disney owns everything), staring at the sky in amazement that a fireworks show was happening “just because.” I started snapping images.

I didn’t use the flash (#rookiemistake), so the prints consist mostly of a few spots of light and a rough outline of some mouse ears. But holding the photos, I remember what the fireworks smelled like, how it was humid but not hot, that my hands were sticky from holding the boys’ popsicles, that I almost cried watching two brothers share a special moment. The snap of the camera imprinted it in my mind for all time and eternity. It was just like magic.

This story originally appeared in the November issue of D Magazine with the headline, “Total Exposure.” Write to [email protected].