From November 2022

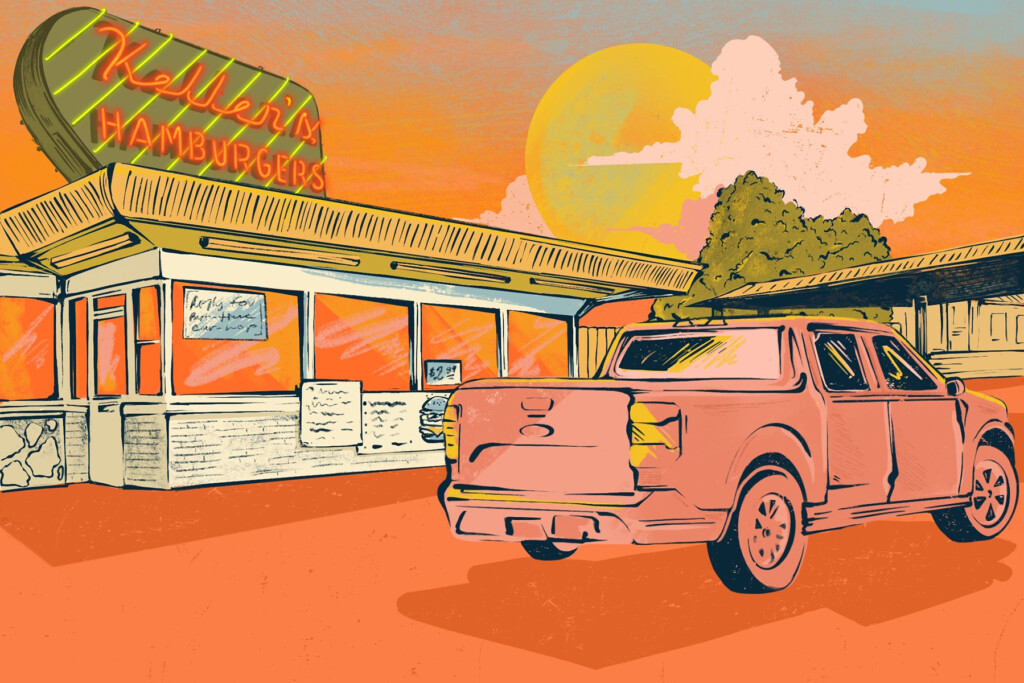

The window lowered, and the Keller’s Drive-In carhop leaned in on my brother’s passenger side and announced, “Your truck looks weird.”

I possessed no energy to respond to this critique of my 2022 Ford Maverick, which, thanks to prompting from the Ford Pass app, I had named Boots in honor of my late grandmother’s favorite poodle. The setting sun cast an orange, vintage-California-postcard hue across the rows of cars and trucks full of families, couples waiting for burgers on that summer Sunday evening. The temperature in Northeast Dallas still clung to its three digits of heat.

After I’d spent a day opening enough moving boxes to fill half of an 18-wheeler, the Keller’s burgers served as a reward for that sweaty work and as an emotional balm for me. I’d lived for two decades outside of my home state, and unpacking that life brought two conflicting realizations: a human can acquire a ridiculous amount of stuff, and that stuff can deliver a sucker punch of sadness when you open a box and see it shattered (my huge, vintage neon Speak Easy Club sign from a dive bar in Binghamton, New York; the wingback chair from my dad’s bedroom; the first imprint of my daughter’s hand captured in a circle of clay in a kindergarten project).

And as strange as it sounds, Boots helped lighten the weight of all I’d left, all I carried as I returned to Dallas, the city where my professional career had started, where my daughter had been born, where my marriage had begun and ended. This “weird” truck reminded me that new, different and yet old, familiar could be a good thing, a message I needed on the regular.

“I’m moving to a house I’ve never stepped foot into and to drive a truck I’ve never sat in.”

Of course, our waitress didn’t know she was stepping on a metaphor when she took aim at Boots. She wore cutoffs, a white t-shirt, and purple cornrows that fell past her shoulders, framing her porcelain face. “I drive an F-150,” she added. “It’s out back.” She pointed across the parking lot to a weathered beast of a truck that first hit the road sometime in the ’90s. “I was in a wreck last week,” she continued. “I ran into someone. Didn’t do a thang to my truck.” Then she reached inside Boots and ran her hand across the dashboard. “This is all plastic. My truck is all metal. That’s why I had no damage.” As she spoke, a pack of seven or eight motorcycles roared past on Northwest Highway, and she spun her head around, watched, and returned her attention to our order.

On the drive back to my new house, my brother, an auto obsessive, shared that the dashboard of her 1990s F-150 would, in fact, be made of plastic. Boots and I felt a bit better about ourselves. But the carhop wasn’t the first to question the truck. When I texted my real estate agent to ask if, by chance, the sellers had received my truck paperwork and plates due to an error on the part of the dealership, she responded in a text: “What kind of truck? Like a truck truck or like an SUV? Just wondering how Texan you’re becoming.”

I shared her concern. In the beginning, before I returned in Dallas, I enjoyed telling everyone in Syracuse, New York, who asked about the details of my life’s hard-left turn: “I’m moving to Dallas to a house I’ve never stepped foot into and to drive a truck I’ve never sat in.” The truck was easy to explain. I needed a new car, and my brother had ordered the Maverick for himself. But it took too long to arrive, and being an impatient car nerd, he did what most Texans would do: he gave up and bought himself an F-150. So when the hybrid truck with the short bed and every imaginable extra appeared in March, I figured I’d take it and enjoy having one less decision to make. I also feared my 2004 snow-eating Subaru with its “I heart Texas” sticker and its 150,000-plus miles might leave me on the side of Central Expressway. I sought to avoid that.

But my agent understood the house part of the story. From our first phone call, she schooled me on the challenges of the Dallas market. All-cash offers helped land homes. Some desperate buyers added enticements such as all-expense-paid vacations. All homes required quick decisions. I visited Dallas in February on a house-hunting trip just weeks after Freakonomics dropped a two-part podcast titled “Why Is Everyone Moving to Dallas?” That felt about right.

Most of my search, though, had to be conducted on a phone. My agent acted as my Spielberg for every home tour, sending me videos of the houses I thought might work and the neighborhoods. On the video of the house I ultimately bought, taken by my agent at an open house, she strolled through the hyper-styled rooms (bold-colored statement walls, light fixtures constructed from what appeared to be woven baskets, a green velvet couch) of the midcentury modern in Highland Meadows. As she navigated the groups of fellow domicile-seekers and the seller’s agent cackled in the background, she stepped outside, whispering to me on the video, “Multiple, multiple offers already.” In a panic and for the heck of it, I searched Zillow for the first house I’d bought in Dallas. In the early ’90s I paid $110,000 for an M Street-adjacent corner lot off of Skillman. It recently sold for $1.2 million.

Friends and family members who saw the video of my new house all offered a version of the same response: “It’s soooooo modern.” All those commentators had spent time in my 1915 arts-and-crafts Syracuse bungalow, which boasted a second-floor sleeping porch, cut-glass windows, a claw-foot bathtub, original, unpainted wood trim for days, and a glorious gingko tree out front that transformed into a tower of shimmering, golden yellow in the fall. I loved that house, and when a real estate reporter for the local paper called to ask if he could feature it as the “house of the week,” I considered it a life achievement that might make good material for my tombstone.

When the story appeared in the paper, it prompted many emails asking why I would leave a great job in Syracuse for “crazy, hot Texas.” I found this somewhat amusing coming from people who live in a city that ranks in the top 10 list of the most gray cities in the country. I participated in many a conversation about the need for “happy lights,” an apparatus used to offer light therapy to combat Seasonal Affective Disorder. My former employer even offered a mind spa that featured a light therapy box. Syracuse also competes for the “golden snowball,” which goes annually to the city in Upstate New York that earns the most snowfall. I still remember the day I signed the papers on my first Syracuse home, and the agent shared with me that as a mom with a kindergartner, I should know that the city schools close when the temperature dips to -20 because children with exposed skin due to a lost glove or lack of a face-covering winter hat might get frostbite waiting at the bus stop. That gave my contract-signing pen a pause.

But I knew more than weather fueled those comments about Texas. And as I fielded questions about why I would leave and made my case for my state in general, and Big D in particular, it reminded me of all the times I had defended my home state after I’d left. I have explained horses, guns, brisket, the television show Dallas (yes, still), and politics. (My recent favorite included an unpacking of the difference between a “yellow dog Democrat” and a “blue dog Democrat.”) Before Syracuse, I lived for four years in Birmingham. I remember thinking I would get Alabama, and it would get me because I’m a Southerner. I quickly learned Alabama and the Deep South see my state as part of the Southwest and approach outsiders much like the wee town in Scotland where I lived for six months: if you don’t have a grandparent in the local cemetery, you’re not a local. In Birmingham, my friendly waves as I passed neighbors in my minivan with my daughter went unanswered.

The first time I returned to Dallas after moving there, I stood in an elevator as a FedEx employee entered with a package. “Howdy,” he said. I gleefully returned, “Howdy.” When I applied to the job I landed in Syracuse all those years ago and mentioned I had attended Baylor University, the associate dean interviewing me asked, “Is that journalism school even accredited?” When I interviewed for my new job in Dallas, mentioning Baylor earned smiles and a game of do-you-know.

In the end, my time away from Texas made me pine for this place and made me more of a Texan than when I left. Of course, my family—all of whom live in Texas—would balk at this statement.

In the end, my time away from Texas made me pine for this place and made me more of a Texan than when I left. Of course, my family—all of whom live in Texas—would balk at this statement. “You’ve spent more time as a Yankee than you have as a Texan,” my aunt announced a few Thanksgivings ago. They also enjoy pointing out other Lone Star crimes: I don’t “sound like a Texan,” I don’t know how to cook a proper batch of fried chicken, and I really should be living “on the land,” a stretch of land in the piney woods of East Texas that connects to many generations of my family and that my grandfather spent his life buying and consolidating.

But at work in Syracuse, people considered me very Texan and often commented on my use of a Southern expression to make a point. “Hold on, Trigger,” I’d say to a student. Or I’d refer to a problem or a situation as a “crazy quilt” or add a well-placed “swing low” or a “bless his heart” or a “that dog don’t hunt.” And when I really wanted to pour it on, I referenced my status as a sixth-generation Texan. I never felt the need to use those expressions or drop my generational cred before taking up residence a few hours south of Canada. I also never listened to country music of any flavor when I lived in Texas. I still remember my morning drives to work from Dallas to Fort Worth and blasting Public Enemy with a cup of La Madeleine coffee in my hand. In Syracuse, I built a mezcal collection, and for my last concert, I coerced a friend to join me to see The Chicks. And I’m embarrassed to share, but when the movers finally arrived at that midcentury house with my furniture from Syracuse, I greeted them with a Gas Monkey Garage t-shirt and a hat I bought from Boot Barn one Christmas when I experienced an emergency hat need. It features a stitched rendering of the state.

“Are you from Texas?” one of the movers asked.

“Yes,” I said. “How did you know?”

“All the gear,” he offered.

But something more than hats, trucks, sun, and sunny people called me back. In the spring of 2021, I stood on a cinderblock beside my mother and brother outside of a window on the COVID ward of a hospital in Lufkin. From that spot and with my iPhone in hand, I watched my father take his last breath while FaceTiming with a nurse. For years I’d promised him I’d move home. Then, the fall after he passed, a colleague mentioned a position she’d seen in Dallas, and I applied on a whim for a job that excited me and offered a way back. I thought of him on the first night in my new house.

On my visits home to East Texas, after a great seafood meal at his favorite restaurant, we’d drive home with the radio blasting and sing together to every song the classic country radio station played. We moved through the night, carried by Hank Williams, George Jones, Tammy Wynette, and Patsy Cline, as the country road dipped and rose. Whatever sliver of moon appeared in the sky would illuminate the rows of pine trees that flanked our road.

I thought about those nights as I prepared for my first night in Dallas. It would be days before all my material possessions and my brother arrived. I took blankets I’d borrowed from my mom’s house and piled them up in a stack by a front window. I brought a sheet to hang for privacy, but instead, I kept the window bare. Outside an army of oak trees on both sides of the street linked branches, creating a canopy. A lone streetlight cast shadows, and I watched as a possum appeared and headed for a neighbor’s house. I remembered that a colleague who had the good sense to marry a woman from Taylor, Texas, and live in Austin for a good bit had told me earlier that day that they wanted to give me a pecan tree as a housewarming gift.

“You’re from Texas,” he said. “You need a pecan tree.”

That forthcoming tree changed my mood from “The moon just went behind the clouds to hide its face and cry” to “That’s right you’re not from Texas.” I fell asleep thinking about the spot in my backyard where I planned to plant that pecan.

Melissa Chessher is a professor at SMU, where she holds the Belo Foundation Endowed Distinguished Chair in Journalism. This story originally appeared in the November issue of D Magazine. Write to [email protected].