From November 2022

Gravel crunched under my tires as I pulled into the empty lot of the old gas station: neutral gray and abandoned, the front door padlocked under the awning. When I got out of my car, I could almost hear the sound of a Coke bottle landing at my feet with a coded message from Bonnie and Clyde scrawled inside, launched from their speeding vehicle.

My search for Dallas’ buried history had led me here, the former Barrow gas station in West Dallas, once owned by Clyde’s father. In the 1930s, the exterior would have read Star Service Station, but, as I stood there in October 2012, I saw no signage, no gas pumps, no people. This is the kind of place that inspires my artwork: a structure in between its former and future identities, left abandoned to the elements without plaques or preciousness.

I believe we can connect to the past by sharing the airspace of a physical location. This belief had taken me to sites such as the dead zone leading up to the former Berlin Wall, the 9th Ward in New Orleans post-Katrina, and Detroit’s grand, abandoned Michigan Central train station. And now, my desire to better understand the past and how it shapes the present through physical spaces had brought me to the Barrow gas station.

I walked over to the side of the building to study the roofline and the walls. This was where Mr. and Mrs. Barrow, Clyde, and his younger siblings resided. In some strange way, the structure I stood before connected this long-dead family to me. What was it like to move through the mundane details of daily life while your son was on a killing spree? What could the ghosts tell me?

This was the first of many visits I made to 1221 Singleton Boulevard over the following year. Not sure what I was looking for, I started with the most basic facts, using my tape measure to get the building’s literal dimensions in order to understand the dimension of the lives of the people who had lived there. On later visits, I created pencil sketches of the roofline and painted gouache and ink studies in my sketchbook.

I also began to research facts that the building itself could never reveal to me. I compared historical photos from the 1930s to the present day and discovered that additions had been made to the original station, but parts of the roofline remained the same. The awning was covering the same patch of earth from the time of the Barrows, and this felt significant. This structure signified the connection from public to private life. I focused on this roofline and canopy as a metaphor for how change both defines and erases parts of our lives and histories.

I began to look forward to driving up to the gas station because it was such a consistent anachronism in the face of the wild pace of Dallas’ urban development. In its time, the West Dallas area it called home was down and out, nicknamed the Devil’s Back Porch, and this polluted area remained lead-poisoned and ignored until lawsuits in the ’90s pushed clean up efforts. Now, with real estate all over the city at a premium, West Dallas plots were being flipped and developed into galleries, test kitchens, and condominiums. I knew the Barrow station was on borrowed time, and this lent urgency to each visit.

One day, I noticed new graffiti tags marking the west side with white script. I took note but said nothing to my fellow traveler, my grandmother, a sprightly 90-something-year-old native Texan whom I ushered to the wrought-iron gate at the front door, where she smiled for a selfie with me. She had been the first to spark my interest in the legend of Bonnie and Clyde. In some ways, her story wasn’t much different. Like Clyde and his younger siblings, Grandma and her brother were born in Ellis County. And like the Barrows, Grandma was self-educated.

When Bonnie and Clyde’s crime spree began in 1932, Grandma was only 11, young enough to have no memories of their 13 victims. But she remembered the buzz of excitement these locals created as their fame spread across the nation. Her own father also made his living from the oil industry, as a driller, which is why she spent her childhood moving from town to town, living mostly in a tent. She told me that there was news of their crimes happening all around where they lived. As a child, I was already fascinated by the story, but when I’d ask Grandma questions, she would usually answer by singing: “Bonnie and Clyde were lovers, oh how they did love …” Then she’d trail off, humming. Her version of Bonnie and Clyde’s exploits owed a lot to Robin Hood and merged with mythologies of Pretty Boy Floyd, John Dillinger, and other stories of the little guy seeking vengeance on the big banks and sharing the proceeds with his fellow poor.

But as an adult, I knew there had to be more to the story. I drove to the downtown J. Erik Jonsson Central Library and combed through accounts by family and Barrow gang members. I learned that the gas station began as an addition to a home that Mr. Henry Barrow had built with his own hands while he and his family lived in temporary campgrounds by the Trinity River, where he gathered scrap metal in his horse-drawn wagon and sold it to nearby foundries to make a living and buy wood for the house he was slowly constructing.

Nine years later, in 1931, with the help of three of their older children, Mr. and Mrs. Barrow bought land on Eagle Ford Road (now Singleton Boulevard) and moved the house there. The gas station was added over the next year while Clyde was locked up at Eastham Prison Farm for burglary. Even though Clyde was a first-time offender, the jury had thrown a maximum sentence at him. Eastham Prison Farm was a working cotton farm where Clyde was repeatedly raped when he first arrived by a bully he soon killed (a death that was never fully investigated). The workload at Eastham was so intense that they called it the Bloody Ham because so many inmates self-mutilated so they would be reassigned to work inside the walls instead of outside. Clyde himself chopped off a big toe and part of another toe less than a week before his mom’s pleas to the governor resulted in Clyde’s pardon in February 1932.

The structure I stood before connected this long-dead family to me.

Some moments in life act as crossroads, and, according to his sisters, Clyde’s time in Eastham changed him forever. His dream when he was released was to open an auto repair shop next to his family’s gas station, so he bought the empty plot from his dad. He held a job at United Glass and Mirror, on Swiss Avenue, but anytime someone committed a crime in the neighborhood, the police stopped by “on suspicion” to harass him at work. According to his sister, Clyde was an excellent employee at all of his straight jobs. So when he was fired from United Glass and Mirror because, as his boss told him, “cops keep hanging around,” Clyde was exasperated. Within the walls of the gas station, he swore: “Mama, I’m never gonna work again, and I’ll never stand arrest, either. I’m not ever going back to that Eastham hell hole. I’ll die first! I swear it, they’re going to have to kill me.”

Reading these stories taught me things I’d never heard over tea with Grandma. But nothing made the story real to me like returning to the physical place of the gas station. After a number of visits, I was more and more eager to stand inside the walls. I emailed the owners, to let them know I was an artist with a deep interest in the place. It turned out that they also owned the pharmacy next door and had known the location for decades. They had even discovered Barrow family artifacts when they had bought the place and had displayed them in the pharmacy until they had been lost in a fire. But though they were very kind to me, they weren’t interested in opening the building to anyone. It had no electricity or running water, just like when the Barrows lived there. It was boarded up, and they didn’t want to undo that work.

So now, when I returned to the station, my challenge was to glean the interior through the exterior, by glimpses caught through cracks. In the west window, I found that vandals had broken a hole just big enough for my hand. I stood on the window ledge for purchase and reached carefully through the shards, snapping pictures in the dark interior of things that I couldn’t see from where I was standing. When I looked at my snapshots, they showed cracks of light spread across the space through gaps in the windows and doors. My images also captured curious objects from the last tenant: a desk, a 1-gallon plastic bucket, some empty fast-food containers. A basketball-size hole in the floorboards revealed the dirt that would’ve been the Barrows’ floor. The ghosts of the Barrows’ turmoil existed quietly in this spare emptiness, and these photos captured more feeling than I imagined possible.

I shot another set of photos through the front door, where a large sheet of plywood had been wedged behind the wrought-iron door, but I found a crescent-shaped gap in the wood, where the hole had been drilled too big for the door handle. From this tiny aperture, my photos resembled images taken from a pinhole camera with their edges fuzzy, rounded, acting as a halo of soft focus around the scene. The pictures showed a long wall that separated the front room from the back and another hole in the floor, revealing more of the dirt the Barrows had trod.

Since I couldn’t get any closer to the station, my thoughts turned to another location I knew had shaped Clyde’s life: Eastham Prison Farm. I reached out to the Texas Prison Museum in Huntsville and found out that Eastham was much like the gas station: boarded up and decommissioned. These two locations were the crossroads of Clyde’s life. If I could see these walls that so many of these prisoners stared at, perhaps I could get a fuller understanding of him and his family. The warden seemed eager to meet my novel request to explore the prison and spend some time painting inside.

The prison was a much more suffocating space than the gas station. As I examined the geometry of the peeling paint and mixed pigments to match the greens of underlayers of wall paint, I felt the sadness of violence and incarcerations, not just in Clyde’s time but in our own. I used a handheld scanner to rub over the texture of the walls, creating a not-so-seamless picture of an old wall with richly pigmented flakes of peeling paint. The repetition of striated digital errors replaces any would-be nostalgia with a reminder that you are witnessing interruptions of a fragment of reality.

From the prison, I drove back to Dallas and straight to the gas station. As I walked up, I let the surface speak to my eyes. The way the sun discolored the paint and moisture caused it to peel—these are effects that can only occur over time, the same way time weathered the lives and history inside. Hope, determination, despair: we all cycle through them at different times, but at some moments we make seemingly instant pivots, like the moment when blistering paint lifts off the wall and becomes something else.

I pulled a dangling paint chip off the wall near the west window and studied the underside—canary yellow, burgundy, black, and robin’s-egg blue. These buried colors from years past became my palette for the series of Barrow paintings I created in my studio over the next three years.

If you’ve ever seen any movie or documentary on Bonnie and Clyde, their dramatic, fiery ending is a controversial showstopper. In my research, I studied images of the bullet riddled car in which Bonnie and Clyde had been ambushed in 1934. The pattern of bullet holes is a map: of fear, injustice, resistance, revenge, rage, lost life, lost hope. I used this map of bullet holes in my paintings as a lens through which to view everything I’d seen and felt at the gas station.

Material history is not linear. Lives can be studied in many ways: not just as a chronology of events but in the duration of the surfaces we touch and how they touch us. In the studio, I enlarged a print of the bullet pattern and then made a stencil by cutting and removing the bullet holes with a small blade. It became a recurring theme in my paintings, both obscuring and revealing what we can know and see, along with depictions of the roofline and awning of the gas station, which had sheltered and then outlived the family who had built it, and shadows, shapes, and colors drawn from Eastham Prison.

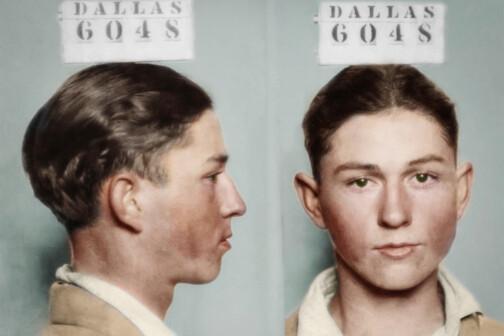

The legend of Bonnie and Clyde was born in images. Their outsize persona was due to a roll of film found in a 1933 police raid of their hideout and subsequently published in newspapers across the country. Photos of the fashionable couple vamping for the camera with guns and cigars created an adventurous love story more compelling than any mug shot or list of crimes. It wasn’t until images surfaced of Ms. Tullis in her wedding dress at the funeral of her young fiancé, H.D. Murphy, shot dead by Bonnie and Clyde 12 days before their wedding, that the public’s sympathy started to turn. Through images, the criminal lovers on the run morphed into violent and cruel heartbreakers.

As a creator of images myself, I wanted to paint the accumulated story of the historical gas station. Time and memory are the actors, but surface is the stage. Years after Bonnie and Clyde were killed, public anger still waged retribution against the gas station itself. The station withstood multiple firebomb attacks, and Mrs. Cumie Barrow survived gunshot wounds while outside her station in 1938. My paintings studied the gas station and the traces of the lives it held.

As I layered latex black, joint compound, shellac, vinyl yellow, and clear coats, creating darkly textured surfaces with chiaroscuro-clarity, the shapes of the station did begin to speak to me. They told me about the persistence of those left behind. The focus of my paintings became the light that slipped through cracks to illuminate the darkness. The station itself had almost been erased: no sign, no pump, no color but neutrals. But light still cascaded across its face and poured inside through every gap it could find, creating captivating shadows that were the swan song of the building’s final years.

From the time I first saw the Barrow station, it felt precarious to me, so easy for it to slip out of history. And so it has. Even though the city’s Landmark Commission was working to preserve it, confusion and delays created by the pandemic allowed the new property owner to demolish the Barrow station in April. When I return to the site now, I stand on a level dirt plot with all the traces of the former Barrow residence fully erased. I’ve spent years learning the place, as intimately as perhaps anyone else in this age. But when I try to remember exactly where the front door stood, I can’t.

Star Service Station exists now only in memory. But to create a true sense of the place, I had to be there. In the actual space, I learned things I couldn’t learn any other way. And I hope somehow that the things I learned are shared by viewers when they stand before my paintings: things that we can’t learn from pictures or books or screens. Things that we can learn about ourselves, our world, our history, only by being there in the place.

Michelle Mackey has been a resident at Vermont Studio Center, Brush Creek Foundation for the Arts in Wyoming, and 100 W Corsicana. She has had solo exhibitions in Berlin and New York, and she has participated in group exhibitions in Dallas, Marfa, Brooklyn, and New York. She now lives and works in Dallas. You can find more of her work at michellemackey.com.

This story originally ran in the November issue of D Magazine with the headline, “These Walls Could Talk.” Write to [email protected].