Ever since i noticed the “for sale” sign, around Halloween, I had been nervous. That unease turned to despair the second week of January. I’d picked up our youngest son from his preschool at Preston Hollow United Methodist Church and was taking a scenic route home. We went up Tibbs and turned left on Glendora. As we approached Preston, I saw the “for sale” sign had changed to “sale pending,” and my heart sank. My gasp and following “Oh no!” alarmed my son.

“Mama sad?” he said from the back seat.

“Yes, Patrick. Mama sad.”

You know the house. On the northeast corner of Preston Road and Glendora Avenue, framed by nearly century-old magnolias, pecan trees, and a rambling bois d’arc fence dotted by stunning tea roses, sits an original Preston Hollow estate. Since childhood I have loved 6007 Glendora and wondered what it would be like to live there.

Until I was 7, I lived with my family on Alta Vista Lane, just behind the Hockaday School. My mother’s best friend and business partner lived on Glendora, and we covered the distance between our house and hers frequently; Alta Vista to Strait, Strait to Northaven, Northaven to Preston, Preston to Glendora. Left on Glendora, a slow left in my mother’s navy four-door Oldsmobile, listening to 103.7 KVIL. Just tall enough to see out the back window, I’d look for the roses. If we went a different route, I’d ask where they were. The house seemed like a palace to my wide little eyes. I wondered who lived there and if they had a canopy bed in their room. Was there a little girl my age? Did she have a dumbwaiter like in the movies? Was she allowed to pick the roses? Did she slide down the banister? This was a huge thing for me. Always the resident of a one-story home, I longed to shimmy down a banister. I hoped someone in the white house was taking advantage of that tremendous asset.

It is a sad reality, but in this part of town, “sale pending” signs should really read “demo imminent.” With the exception of a handful of remaining Dilbecks, there’s not much left of the original hamlet of Preston Hollow. The 2019 tornado that barreled through this part of town showed us what happens when you lose points of reference. It was disorienting to drive down a newly treeless Royal Lane the morning after the storm, and for countless mornings after, unable to fully locate yourself, no matter that you were driving on streets you’d known for 40 years. In that sense, a wrecking ball works just like a tornado.

So it was with melancholic curiosity that I set out to learn more about 6007 Glendora before it was gone for good. I came to learn the home was owned by the Witts family and was delighted to connect with their daughter, Elane, who graciously took a call from me while she was walking through the home one final time.

“I’m not surprised to hear from you,” she said. “People have been coming out of the woodwork over this house.”

The house had been her family’s home since her grandparents bought it from the original owners in 1946—just one year after much of the township of Preston Hollow had been annexed by the city of Dallas. Elane’s grandmother Salome Travis wrote her husband, Lee, to let him know she’d found the perfect home for them. Lee was an East Texas oilman and often left his wife on her own for stretches of time, so it was up to her to establish their home in the growing city of Dallas.

“I’ve found the most lovely country estate,” she wrote. “We must buy it.”

It was indeed the country at that time. Preston Road, not far removed from its original function as a cattle trail and stagecoach line, was only two lanes, and there was nothing much to see aside from the smattering of lovely, roomy homes being built on large lots.

At the time of the purchase, their daughter Jean was one of the first women to attend the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business. After college, Jean would make a living as a piano teacher and dancer in Los Angeles. During a visit home to Dallas, Jean had a blind date with a man named David Witts, who would turn out to be the love of her life. They met in Dallas but married in Los Angeles. As newlyweds, they made their way home to Texas, and, because Jean’s father traveled for work so frequently, the new Mr. and Mrs. David Witts moved into 6007 Glendora to keep Jean’s mom company. They stayed, maybe longer than they imagined, and in 1956 welcomed their only child, a girl named Elane, who spent her entire childhood in the beautiful white house with the famous roses, living alongside her mother, father, grandmother, and grandfather.

Elane remembers the times the doorbell would ring, and a family would be standing there, asking for permission to have their family Christmas card picture made among the roses. In the mid-’60s, the house was featured in Southern Living—a love letter to the beautifully manicured yard. When her grandfather passed away, in 1969, her parents assumed responsibility for the roses and the fence and the magnolias and the pecan trees.

“I don’t know if anyone was as passionate about the roses as my grandfather, but it was important to us, and they were so beautiful,” Elane told me. “I’ve been going through boxes and boxes in the house and found hundreds of little sticks on which my grandfather had written the names of all the roses.” Their own little placards, tucked throughout the house.

The only time strangers were ever asked to leave was when people would try to pick their pecans and roses. “We had to shoo people away pretty often. Actually, I had to shoosh a man off the lawn about three weeks ago. Those are my pecans!” Elane said, laughing.

I wonder if her grandmother could have imaged how lovely her “country estate” would become when, after they’d settled in, her husband had the signature bois d’arc crossbuck fence made that bordered the property for over 70 years. I wonder, too, if she knew about his love of roses and how he would plant hundreds of them over their lifetime as residents there.

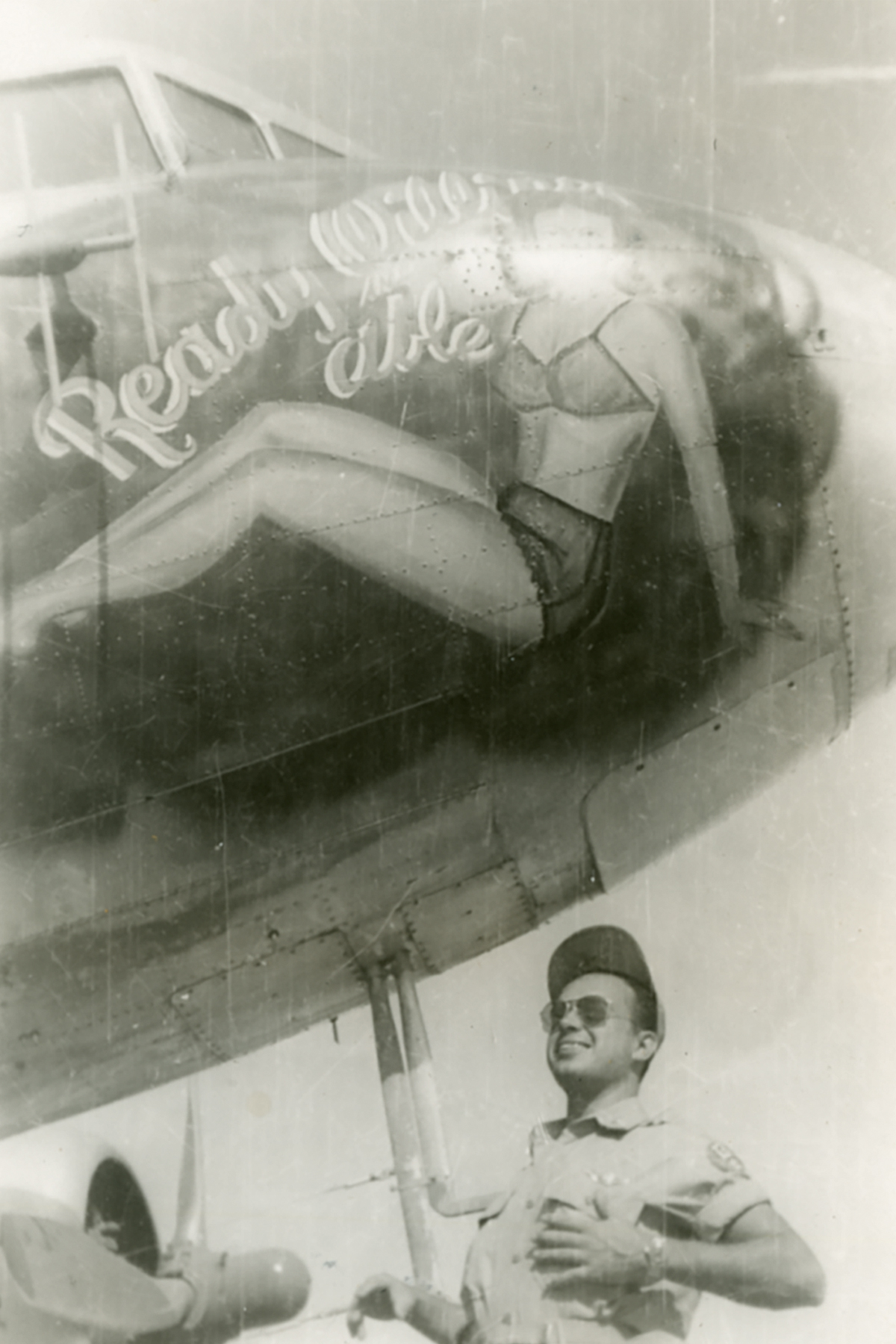

Elane’s parents deserve their own documentary. David, a University of Texas grad, served one year with the FBI, breaking up backroom gambling rings in Beaumont, Texas. “Think fedoras and trench coats and lots of black-and-white newspaper pictures,” Elane said. After the Bureau, David joined the Army Air Corps to fight in World War II. As a search and rescue pilot, he flew 50 missions in the Pacific theater.

After the war, he earned his law degree from SMU and became a corporate attorney, representing many high-profile clients in Dallas, most notably Carroll Shelby, the legendary race car driver portrayed by Matt Damon in Ford v Ferrari. Shelby was not only a client of David’s but a lifelong friend. Together they bought some 150,000 acres of land in Big Bend and inherited the ghost town of Terlingua in the process. What to do with a ghost town? Make a city council, of course. David was self-appointed mayor, and Shelby was social chairman. The Terlingua City Council’s first order of business was to create a chili contest. Dallas Morning News columnist and chili connoisseur Frank X. Tolbert had publicized a feud between Wick Fowler of Austin and Allen “Nobody Knows More About Chili Than I Do” Smith of New York. The Terlingua Chili Cookoff was created to decide the matter. Legend took hold after the first affair, in 1967, and while David Witts’ might not be the name most often associated with the festival, it should be.

Jean and a bunch of the other “chili wives” got in on the action, too. The original chili cookoff was a male-only deal. This didn’t sit well with Jean. So in the second or third year, a bunch of the wives chartered a plane and flew down to Terlingua the first weekend in November. They had the pilot fly low so that the ladies could throw leaflets with strongly worded protests about their exclusion. Never again would they be excluded. Elane laughed mightily while explaining that this was the reason she was able to attend the cookoff for several years in the ’70s, creating many wonderful memories with her family.

When David died, in 2006, Elane and her husband, John, and their two girls, Emily and Cassidy, worked diligently to ensure Jean could stay in her beloved home. In her last few years, mobility became a challenge, and a chair was installed on a banister to guarantee safe comings and goings. At last, someone was shimmying up and down the banister on the regular. A lifelong redhead, Jean visited her hairdresser, Tom Slate, for 50 years, twice a week, to have her hair set and color maintained. When the pandemic arrived, Elane accompanied her mother to her final appointment at the beauty shop and recorded Tom washing and setting her mother’s hair so she would be able to do it for her at home.

Jean died two months shy of her 100th birthday, in 2020. They had to host two estate sales to clear the house. Elane couldn’t bring herself to attend—it was too much. Emily and Cassidy, Jean’s beloved granddaughters, did go to both sales and reported shopper after shopper was there to either pay last respects to the family or to simply purchase a piece of a landmark they never thought they’d say goodbye to.

“It was really overwhelming and so special,” Elane said. “People would come in and just say, ‘I knew your mom,’ or, ‘I’ve always loved this home.’ ”

For over 40 years, a man named Tommy Carty maintained the exterior paint for the family. He began touching up the white house when he was 18 years old. Elane said he was one of the first calls when the house hit the market. He was saddened to learn the house was for sale but wanted to know if he could have the ladder he’d always used, all those years, the one that lived in the garage.

The house at 6007 Glendora was torn down on a gray, balmy Friday in March. A bulldozer had shown up a day earlier, and I’d been circling the block, on and off, for 24 hours. My 5-year-old and I drove by around 3 pm. It was a pile of rubble. I’d seen it earlier that morning and it had been standing, and now here it was: a pile of wood, pipes, insulation, wallpapered walls, a kitchen sink.

In the mid-’60s, the house was featured in Southern Living—a love letter to the beautifully manicured yard.

I stopped in the middle of the block and stared. A few cars turned onto Glendora behind me, but they didn’t honk or attempt to go around. I don’t know if they were there to watch, but they seemed to respect the fact that I was. We all sat there, watching as the bulldozer continued its work. I swear the driver gave me a mournful nod, looking almost ashamed about his task.

I texted Elane to see how she was doing. It had been a hard day. That morning, her husband had gone to the house and spoken with the demo team. The team lead had said it was a hard job for him, that it was difficult to demo such a well-built house. Her husband then had basically forbidden Elane to drive by the house again.

We can’t fault the new owners for scraping the house. Like so many of the properties in the neighborhood, including my own, it was built with cast-iron plumbing and parts and pieces and wiring that don’t come close to conforming to code. The cost to get things up to date would be backbreaking. And if the house were updated—the kitchen made more functional, the bathrooms more luxurious—it wouldn’t be the same house. The dents in the linoleum floors from years of running and dancing and rearranging furniture would be gone. It would literally be a shell of itself.

There’s a traffic light just one block north of the now vacant lot where 6007 Glendora stood for 86 years, and each day, thousands of people pass through that light, moving at 35-plus miles per hour, unconsciously navigating using neighborhood standbys as their cardinal directions. Green, yellow, red, all day, all night, over and over and over; the cadence of the light and the traffic that triggers its pace ebbs and flows with the rhythms of the day, even though the landscape has been forever changed.

Some people who pass by will notice the hole where the beautiful home once stood, and they will run a red light at Meadow because they can’t look away. Others won’t notice a thing. They will focus on the car in front of them or let their eyes glaze as they listen to the radio and their mind wanders through whatever minds wander through while coasting down a familiar street, and they will drive on, totally unfazed at how another home that silently mattered to countless passersby was razed and will be replaced with a trendy palace that is the polar opposite of the understated elegance that used to reside there.

I will always, always look for the roses. It’s muscle memory. If I approach that corner, I will look for them, and my heart will ache for the time in the back of my mother’s blue Olds, listening to KVIL and seeing those beautiful blooms in my line of sight.

It might be time to pick another route.