Gambling operations are illegal in the state of Texas—unless you’re talking about the Texas Lottery—which is why the city of Dallas is trying to shut down a poker room that it approved for business. The Texas Card House sits off Harry Hines Boulevard, past the strip clubs, sex shops, and shady theaters that line the city’s de facto red-light district, in a strip mall next to the Sam Moon Trading Co. On a gray Monday afternoon in January, I find it brightly lit and packed with players ranging from twentysomething gamer types to gray-haired retirees. It looks more like a La Quinta breakfast room than a den of sin.

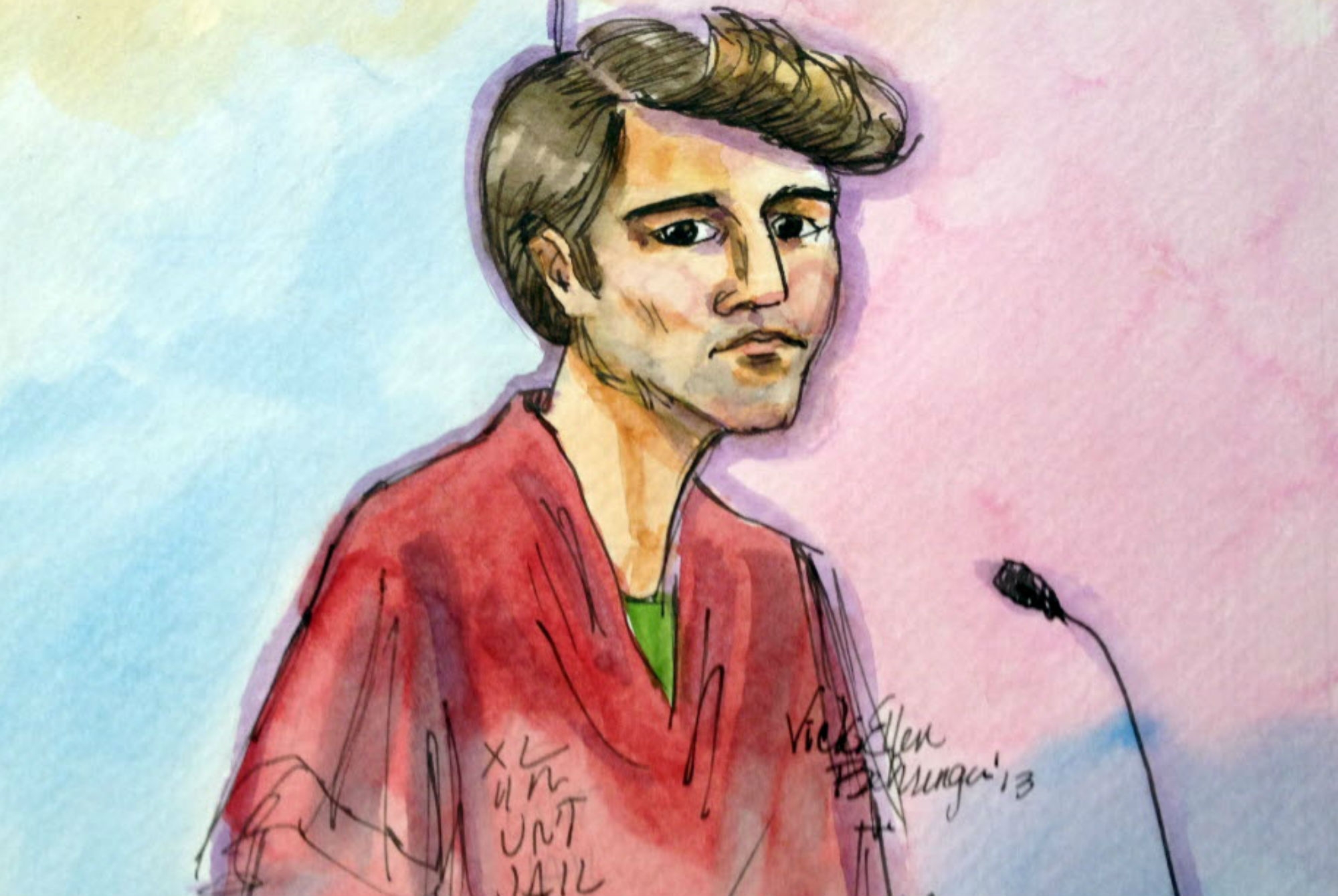

Ryan Crow, Texas Card House’s CEO, shows me around. He is clean cut, with neatly parted hair and a puckish grin, more business school bro than Scorsese gambling goon. He tells me business has been brisk since they opened in October 2020. Texas Card House has a full production studio tucked in a back room. Their regular YouTube streams, complete with commentators breaking down the action, reach 41,000 subscribers.

“We knew when we opened it was going to be busy,” Crow says. “But we didn’t know how big some of the games would be. When we do a tournament, people fly in internationally.”

But in December 2021, Crow received a letter from the city revoking his certificate of occupancy and instructing him to close his doors. He was shocked. Before they opened, Crow had met with elected officials, the Dallas Police Department’s vice squad, and the Dallas County District Attorney’s Office. He explained how poker rooms could operate legally in Texas and how they can kill underground games, eliminating the robberies, drugs, and prostitution that often accompany them. Dallas is actually late to a boom in poker rooms across the state. Texas Card House opened its first location south of Austin in 2015. There are now more than three dozen poker rooms operating in Texas.

Dallas seemed to be following suit. During a 2019 City Council meeting at which bemused members discussed Texas Card House’s permitting process, City Attorney Chris Caso explained how it all works. Texas’ penal code offers an exemption to the state’s gambling ban if operations meet three criteria. Games must take place in a private place, organizers cannot benefit economically from the action, and the players must assume equal risk. The spirit of the law prevents cops from raiding poker night in people’s homes. It also allows for charity events and country club card rooms.

Texas Card House founder Sam Von Kennel wondered if these three criteria—in legal jargon, the “defense to prosecution”—also suggested a business model. If a private poker club required memberships and didn’t take a “rake,” meaning a cut of each pot, it could meet the letter of the law. In 2015, Von Kennel went all in.

There’s a term for this kind of business: “regulatory entrepreneurship,” which was coined by two law professors, Elizabeth Pollman and Jordan Barry, in a 2017 Southern California Law Review article. Essentially, regulatory entrepreneurs make business bluffs, building companies that “plan to change the law—and, in some instances, to simply break the law in the meantime.” Examples include Uber and Airbnb, both of which grew so fast that by the time lawmakers tried to address the way they affected labor markets or housing supply, they were “too big to ban,” as Pollman and Barry put it.

Crow’s investment group bought Texas Card House from Von Kennel in 2015. The Dallas room became one of the company’s most popular, in part because it drew players away from the city’s thriving underground scene, which has a rich history. Texas Hold ’em is believed to have been popularized in Dallas in the 1920s. In the ’30s and ’40s, rival gangsters Benny Binion and Herbert Noble ran illegal casinos throughout the city before they moved on to Las Vegas. The city was also home to the AMVETS Club, a poker room that operated on Lower Greenville Avenue, across from where HG Sply Co. now stands, from 1969 to the 1980s. Poker Hall of Famers such as Doyle Brunson and “Amarillo Slim” Preston played there.

Not that keeping history alive has anything to do with the current state of affairs. After Texas Card House came Shuffle 214 in Northeast Dallas and Poker House Dallas near Brook Hollow Country Club. The city began to shift its stance on poker after a fourth card room, the Champions Club, attempted to open in the former III Forks restaurant off the Dallas North Tollway. Champions made two crucial errors. Their location was a stone’s throw from the Bent Tree North Homeowners Association, and it was in a part of Dallas that lies in more conservative Collin County, where the district attorney has taken a hard-line stance against poker rooms. North Dallas Councilwoman Cara Mendelsohn initially signaled support for the clubs, but, after constituents spoke out, she reversed course.

“I’ve been asked by my church to register a protest against them being allowed to open,” said Jeffrey Hurt, a member of the Church of the Holy Communion Cathedral, at an October Board of Adjustment meeting. “We do not believe a gambling location near our church is at all appropriate.”

The board rejected Champions Club’s application for a certificate of occupancy, so club owners sued. When I contacted the City Attorney’s Office, the Building Inspection Department, and Mendelsohn, they all cited that lawsuit as the reason they couldn’t talk.

But as I dig through the archives of the Board of Adjustment hearings, another architect of the city’s war against poker emerges. Senior Assistant Attorney Gary Powell was hired by the city in 2021 after a 36-year career in private practice and was tapped to investigate the poker room kerfuffle. Powell broadly interprets the state’s gambling prohibition, arguing that the “defense of prosecution” justifications made by the poker rooms don’t hold because gambling is specifically outlawed in the Texas Constitution. Gambling won’t be legal in Texas, Powell has argued, until the state amends its constitution.

“I’ve dug into this probably about as deep—I’m confident probably deeper than anybody in the room and probably about the top 10 or 15 in the state,” Powell immodestly offered during a November meeting. “I understand what is allowed here and what is not allowed.”

Powell might be right. If the courts agree with him, he could spark a legal chain reaction that could bring down Texas’ fledgling legal poker scene. Not only that, but his broad interpretation of Texas’ gambling laws may impact other organizations. If the “defense of prosecution” arguments apply only to penny pot poker games around the kitchen table, as Powell seems to suggest, what about all those charity casino nights? And will a stricter interpretation of Texas’ gambling ban force a clampdown in card rooms at country clubs?

The answers to those questions will likely come only after a legal battle. After this article went to press in February, the Board of Adjustment was scheduled to hear the Texas Card House appeal of the revocation of its certificate of occupancy. If that fails, Crow told me, he will likely also sue the city. (The Board of Adjustments decided to delay its ruling until March 22.) Thus far, Attorney General Ken Paxton has not weighed in on the issue, despite Arlington state Rep. Chris Turner formally requesting an opinion after a poker house operator began exploring a location in that suburb.

The battle over poker brings to mind some other recent legal fights the city has waged from atop a high horse. The same week I visited Texas Card House, the City Council was deliberating an ordinance that would force the city’s sexually oriented businesses to close at 2 a.m. It passed, and, within hours, the affected businesses sued. Back in 2016, billionaire Ray Hunt and former Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison pushed the city to ban the Exxxotica porn convention, only to leave taxpayers with a $650,000 legal settlement when courts ruled the ban was unconstitutional.

The city’s aversion to poker rooms seems to be as much about a deep insecurity as it is about gambling law. Dallas is both a Bible Belt city and a frontier town. Civic leaders’ efforts to project a polished image have long been undermined by the city’s reputation as a destination for gambling and sex. Had the Champions Club never tried to open just a few blocks from the churches and schools of Bent Tree, Gary Powell might never had fallen down his legal rabbit hole that may end up leaving taxpayers, once again, paying for the fallout of a moral crusade no other city in Texas has opted to wage.

But if Powell is right, and if the courts decide to close the loopholes that have created Texas’ poker rooms, then the city—and the state—should respond by pushing to amend state law or the Texas Constitution to allow operations such as Texas Card House, which have already shown the value of lifting Dallas’ poker scene out of the shadows.

At Texas Card House, I met a former underground dealer who asked not to be named. She told me that a few months before Texas Card House opened, there was a stabbing at an underground game involving a well-known local player. She was relieved that there was now a safe place to play.

“There was a rash of robberies,” the dealer told me. “Multiple games were hit. Some games called the police. Other games did not call the police because they were afraid.”

If the city succeeds in shuttering above-board poker rooms, she said, it will just force players back underground.

“If the city shuts them down, they are still going to play,” the card dealer told me. “They are not going to quit playing.”

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author