Nekeya Webster let her father into her life exactly three times: once in college, when she decided she needed to meet the man who could help her understand the other half of herself; again a few years later, when Webster convinced him to live with her for a few months; and finally in the days after Christmas 2018, when the medical examiner’s office called to let Aldo Busby’s next of kin know he had been discovered dead at a bus stop.

The first time they met, Webster was 21 years old. “He said everything that a person will need to hear,” she says. “And all of a sudden, in a moment, I realized that the man that I thought had to be a monster my whole life was the sweetest being I had ever met before.” She learned that Busby had been abused as a child and had struggled with alcohol dependence for most of his life. He was often homeless.

Webster was a mother and schoolteacher when she tracked down Busby a second time. He proved himself to be a wonderful grandfather, dutifully walking Webster’s daughter home from the bus stop each day. “They really had the bond that I never was able to get with him” in childhood, Webster says. But Busby always had a reason for never staying in one place too long; this time, it was Webster’s divorce. “My divorce was traumatizing to him,” she says with a smile.

When Busby died at age 60, likely from complications of untreated infections, Webster, now 39, was heartbroken. She decided he would have a funeral service that would grant him the respect in death he had struggled to find in life. Webster turned to Golden Gate Funeral Home in South Oak Cliff because she liked their obituaries. The staff helped her plan a crowning ceremony, a relatively recent addition to the African American funeral tradition in which pallbearers would glide Busby’s casket down the aisle and crown him a king. “What I wanted was for him to have dignity,” says Webster, who maintains the commanding presence required of a former K-12 teacher. “That’s why the crowning ceremony was such an important thing for me.”

For Golden Gate, such a service should have been second nature. The funeral home, which serves a mostly Black clientele across three facilities in Dallas, Fort Worth, and Tallulah, Louisiana, is best known for its over-the-top funerals, which were featured in Best Funeral Ever, a short-lived reality show that ran on TLC from 2013 to 2014. Golden Gate’s charismatic leader, John Beckwith Jr., a second-generation licensed funeral director and embalmer, has helped his staff strap a casket to a mechanical bull and arranged for a family to push their loved one’s casket down a bowling alley lane for one final strike. The idea is to celebrate a life, not mourn a loss. “If we continue to work together like I know we can,” Beckwith Jr. said in the first episode, “we’re going to make these families extremely happy at the worst moments of their lives.”

That wasn’t Webster’s experience. At a viewing the day before the crowning ceremony, Webster and other visitors were seated in a large room with other bodies and other mourners, separated by only thin partitions. Webster wouldn’t have minded, except that someone’s remains smelled “horrendous”—a scent she now believes was a sign of decomposition. Golden Gate employees sprayed Lysol around the room in an attempt to mask the odor. While Busby’s remains seemed reasonably well preserved, Webster noticed that no one had bothered to do the basic work of cleaning under his fingernails.

On the day of the funeral, Webster arrived in Golden Gate’s chapel to find it still dirty with used tissues from an earlier event. Webster had arranged with Golden Gate for the gospel standard “I Shall Wear a Crown” to play during Busby’s crowning ceremony, but that day the music never started. When they saw the look of horror on Webster’s face, her pastor and friends spontaneously performed as a makeshift choir. As Webster left the service, an employee handed her a DVD with another family’s slideshow on it.

In the weeks to come, Webster called Golden Gate, hoping that Beckwith Jr. would explain to her how things had gone wrong. She never heard back. Eventually, she set the matter aside and moved on with her life. But a few months later, she realized no one had ever called to ask her to collect her father’s cremated remains.

Webster drove to Golden Gate for an in-person audience. “Now, of all the things that go wrong, I mean, what can go more wrong than dead?” she says. “But I knew something was wrong when they left me in a room by myself for over an hour.” When a staff member finally came back, the woman announced that Webster had waited too long to claim her father’s remains, so Golden Gate had spread them at a site of their choosing, over the state line in Louisiana.

Webster suspected that Golden Gate was lying to her, but she kept the situation to herself for a time, confused, upset, and unprepared to share the news with her family. “I guess I just couldn’t say it, because I was still trying to process that myself,” Webster says. “It just made no sense. I mean, just imagine somebody telling you the stupidest thing in the world, as though this is fact, but you know it can’t be.”

And then the story broke: other families and past employees were coming forward with allegations against Golden Gate. Webster wasn’t alone. Together, their stories paint a portrait of a family-owned company that makes promises beyond its means and then fails customers in the most difficult times of their lives. The families describe a wide range of problems, including damaged corpses and lost or unidentifiable remains. Through it all, they claim to have faced indifference from Golden Gate staff.

In September 2021, as the two-year statute of limitations window was closing, Webster filed a lawsuit against Golden Gate and John Beckwith Jr. seeking more than $1 million in damages for gross negligence. She is one of 25 families and counting who have filed similar suits against the funeral home and its proprietor. They are pursuing answers to questions that haunt them and searching for justice that might be hard to find. Texas is notorious for fostering close ties between the funeral industry and the Texas Funeral Service Commission, the agency that is charged with regulating it—which might explain why the problems at Golden Gate are only just now coming to light.

“It’s like, how long have you been doing this, right? Are you used to people not following up?” Webster says of Golden Gate. “Because surely anybody with good sense, we know that you don’t just all of a sudden start doing crazy things by the masses. You’ve been doing this; it’s just now being caught.”

The funeral industry remains among America’s most segregated, the consequence of centuries of discrimination. The official history of New Hope Baptist Church describes one incident that is emblematic of how things worked in 19th-century Dallas. Family and friends had gathered for a funeral at Freedman’s Cemetery, the designated Black burial ground that now lies under Central Expressway. But the pastor was forced to conduct the ceremony without the body of the deceased, after mourners had waited three hours for a casket to be delivered. When the undertaker did finally arrive, he told the pastor that his White clients had taken priority, and so he had delivered another body first.

This injustice led Black men across the country to serve as itinerant undertakers and, later, to establish their own funeral homes to guarantee reliable, respectful services to their communities. In Dallas, the first such enterprise was the People’s Undertaking Company, opened in 1900 on North Pearl Street by a group of concerned Black reverends and businessmen. The men, who had no formal training in funeral service, divided up the responsibilities of the business, including embalming. Eventually, New Hope Baptist Church raised the funds for William E. Ewing, a Black Dallasite, to attend Meyer’s Embalming School, a White institution in Ohio.

In time, the People’s Undertaking Company closed, but other Black funeral homes opened in Dallas, both during the period of formal segregation and long after Jim Crow ended. These businesses, mostly family owned, aimed to serve a distinct set of expectations among Black clientele for funerals and burials, which were born of African traditions and centuries of enslavement. While the traditional White Christian funeral is often a display of restrained grief, the Black Christian homegoing is a celebration. Families often request an immaculate public presentation of the corpse; hymns of comfort and uplifting gospel songs; and tributes from loved ones and clergy members intended to fortify the spirit of the living.

Today, Dallas’ Black funeral homes number more than a dozen. But every year, they face more challenges. The next generation isn’t always interested in funeral directing. Persistent discrimination means Black business owners are still denied basic loans when they aren’t charged higher interest rates than their White counterparts. And without a clear succession plan, small funeral homes are often acquired or driven out of business by behemoths such as Service Corporation International, a Houston-based company that controls an estimated 16 percent of North America’s funeral market. In 1953, there were 3,000 Black-owned funeral parlors in the United States, according to Ebony magazine; now there are 1,200.

Now, of all the things that can go wrong, I mean, what can go more wrong than dead?

Golden Gate traces its roots to the civil rights movement. Its founder, John Beckwith Sr., then known as Bubba, began working in the funeral service when he was 14, according to family lore. But Bubba, who grew up in eastern Louisiana, on the border with Mississippi, was forced to flee racial terror in the winter of 1964. That December, White supremacists in the nearby town of Ferriday burned down a Black-owned shoe shop with its owner, Frank Morris, still inside. Bubba, who had visited Morris in the hospital before he eventually died from his burns, found himself in the crosshairs. A few nights later, he was working alone at Richardson and Sims Funeral Home when “the phone rang and the caller said, ‘You’re next,’ ” Beckwith Sr. told the Concordia Sentinel in 2010. “He said it three times.” When the owner of the funeral home heard the news, he took Bubba to a bus stop and bought him a ticket to Dallas.

In Texas, Bubba met his wife, Allene, and they had five children. He worked for other funeral homes for a time, before striking out on his own. In 1985, he opened Golden Gate’s Dallas shop, then located in a two-story house in a historically Black neighborhood in Oak Cliff. It has since expanded to its current spot on R.L. Thornton Freeway, and the family opened facilities in Tallulah, Louisiana, in 2001 and Fort Worth in 2010.

Today, Golden Gate’s family legacy remains core to its appeal. Beckwith Sr. is still featured in ad copy for the company, alongside Beckwith Jr. and one of his sisters, Carolyn Haynes, both of whom are licensed funeral directors and embalmers. For a time, Beckwith Jr.’s son, known as JB3 on the TLC series, worked at Golden Gate, too, though the relationship seems to have soured. In 2019, court records show, Beckwith sued JB3 for eviction. But at least five family members have reportedly attended the Dallas Institute of Funeral Service, indicating their intention to keep the tradition alive.

While Golden Gate is an intergenerational business, Beckwith Jr. remains the company’s public face. He was groomed for the role; as a child, he practiced funeral directing with his father in the living room. In 1987, his dad made him acting CEO. “My dad told me, ‘I can’t [point out your mistakes] from the grave,’ ” Beckwith Jr. told D CEO magazine in 2015. “If you are gonna run it, you need to run it now.”

These days, Beckwith Jr.’s thinly mustached smile looms large around parts of North Texas, from highway billboards to Ask the Undertaker, his local television access program and gospel radio show. He’s known for his alligator boots and Italian suits with custom-tailored trousers to holster his .45-caliber Glock. He’s also a licensed peace officer and, at least as of 2015, was a shooting instructor for the Dallas County constables. (D Magazine contacted Beckwith Jr.’s lawyer, Tonika Brown, who declined an interview on her client’s behalf. In part, she wrote: “Any issue, whether it occurred yesterday or 20 years ago, is addressed. Golden Gate follows all state laws and regulations and is in good standing with the Texas Funeral Service Commission.”)

In keeping with his outsize persona, Beckwith Jr. has also stayed true to his larger-than-life goals—namely, that he wants to “bury everybody.” Golden Gate has offered an ever-wider array of services, which now range from $2,500 to $60,000. In 2009, the funeral home said it handled more than 2,000 bodies a year. “That’s big, monstrous,” Bob Duncan, a funeral home supplier, told the Dallas Observer at the time. In 2020, Golden Gate claimed it processed more than 2,800.

To get the job done, the company reportedly employs more than 100 full- or part-time workers, including an in-house florist, dancers, and paid mourners. It has 65 cars in its all-white fleet, including Cadillacs, Chryslers, Lincolns, Mercedes vehicles, and a Bentley. In 2015, Beckwith Jr. claimed he was grossing more than $10 million a year. But just as his self-promotional campaign had reached its crescendo, the first complaints started piling up—first on Google, Yelp, and other online review sites, later in lawsuits now wending their way through the court system.

Melody Palmer, 43, has a box full of mysteries in her house. The cremated remains inside are supposed to be those of her mother, Virginia “Nora” Rankin, who died in December 2019. But after everything that happened between her family and Golden Gate, Palmer says she can’t be sure.

When Rankin died at the age of 63, her children reflexively turned to Golden Gate for the funeral arrangements. “We’ve been to Golden Gate services before,” Palmer says. “So on the outside, you know, it was good.” In talking through the plans with a Golden Gate employee, Palmer and her three siblings decided to hold the funeral and wake in early January, after the holidays, with a cremation at Golden Gate’s in-house crematorium to follow.

Nothing seemed to go according to plan. The siblings had to repeatedly correct information in their mother’s obituary, including her name and age. When they visited the body before the wake, their mother’s fingernails were painted a bright blue against their wishes. When Palmer asked why the staff had made that choice, they replied that her mother’s fingers had started to turn black—a sign, Palmer’s lawyers allege, of decomposition. A slideshow that Palmer’s husband had made of her mother’s life was replaced by photos of a Hispanic family. “It was so unacceptable. And they apologize and what have you, but at that time, at that time, you know, it’s the weight of the world,” Palmer says. “For me, I just couldn’t deal.”

The next day’s funeral, at the Faith Chapel Community Church in Lancaster, went beautifully, as did the repast following the service. The Palmers thought the worst was behind them.

In the weeks to come, however, the Palmers went back and forth with Golden Gate about the state of their mother’s remains. They were repeatedly told she was still in a refrigerator and that her cremation had been delayed by the medical examiner or the nursing home or others responsible for paperwork. But when Palmer’s sister went to Golden Gate to pick up their mother’s death certificate, an employee “came back with a box of ashes saying, ‘Here, got your mama right here,’ ” Palmer says. Her sister became “hysterical.”

They say Beckwith Jr. initially rebuffed their request for a face-to-face conversation, in part because he was busy attending the Super Bowl. When Palmer and her sisters finally got an audience with him, Palmer said it felt like an attempt to control them, not make amends. “It was almost like a pimp, like heavy intimidation,” she says. “He had his well-manicured cotton candy–pink fingernails that were real shiny. And he was like, ‘Ladies.’ ” In a music-themed room in the Continental Gin Building, where her lawyer takes meetings, Palmer leans forward and folds her fingers together, mimicking Beckwith Jr.’s signature pose. “He had on his, you know, his double-breasted tailored suit,” she continues. “And he had his other female [employees]—and I’m gonna speak as candidly as possible, because this is my story. He was up there like a pimp, and these two was his bottom bitches.”

Sensing they had reached an impasse, Beckwith Jr. told the family that if they wanted to continue the conversation, it would have to be through their lawyers. That was a lightbulb moment for Palmer and her family: lawyers, now that’s an idea. They went looking for legal representation and found Ryan Sellers, who filed their suit in February 2021.

Some family members and friends criticized the Palmers for their decision to sue and to publicize it; they were helping a White lawyer to undermine a venerable Black institution. But the Palmers persevered because they felt it was what their mother would have wanted. “I know she would be doing the same exact thing that we are doing now,” Palmer says. “Probably even going even harder—she probably [would have] had picket signs and stuff out.”

Over the course of the year, other families and former employees came forward to tell their stories about Golden Gate, slowly folding the Palmer family’s story into a larger pattern.

In February 2021, former Golden Gate employee Isaiah Darris, who had been learning the ropes at the funeral home for just six months, came forward as a whistle-blower about the alleged conditions of the funeral home. Darris sent a photo to almost 200 news outlets and local and state officials of a rental van with more than a dozen bodies inside in disarray, including one body that was naked and lying facedown on the floor of the vehicle. “It’s like a slaughterhouse,” Darris told Spectrum Local News. “Unless you go behind the scenes and see it, you would never think that just from being up front that it looks the way that it does in the back. And this is not just something that’s been going on since I have been there.” (Beckwith Jr. told Spectrum the photo was staged.)

At the time, the pandemic had pushed funeral homes across the country to the brink. A wave of corpses left many undertakers strapped for storage space, tools, and time. But many of the allegations against Golden Gate, including Webster’s and Palmer’s, predate the virus. The consequences will outlast it, too.

The rest of our lives, we’re supposed to go around just wondering who’s in this box?

“The rest of our lives, we’re supposed to go around just wondering who’s in this box?” Palmer asks. “Whoever it is, they don’t deserve to live in a bag. They deserve to be celebrated.” Palmer says she can’t talk to the cremains as if they’re her own mother and trust that Rankin hears the words.

Golden Gate has resorted to questionable business practices before, as a trail of documents shows. In the late 1980s, murder rates in Dallas hit an all-time high. The victims were often young Black men. Golden Gate sought out the murder victims’ families, who were often short on cash but eligible for the Texas Attorney General’s Crime Victims Compensation Fund, which at the time paid out $3,000 for funeral and burial costs—slightly more than Golden Gate’s average sticker price.

One such client was Retha Mae Sanders, who turned to Golden Gate to arrange for funeral services for her son. Beckwith Sr. allegedly asked Sanders to sign over a $5,000 burial policy she had taken out previously and also to apply for the $3,000 maximum compensation from the fund, which she could supposedly keep when the state paid out several months later.

Sanders declined and instead filed a complaint with the Texas Funeral Service Commission, which later announced an investigation into Golden Gate for “allegedly offering families kickbacks from the state Crime Victims Compensation Fund as an enticement for business,” according to the Dallas Times Herald, which ran the story in November 1991.

That wasn’t the only run-in Sanders had with Beckwith Sr. She said that her stepson was killed a few days later and that she got a call from Beckwith Sr., who was on his car phone waiting in her apartment complex parking lot. “He came up with papers and said, ‘I want you to release the body to me. What was his name?’ ” Sanders told the Times Herald. Sanders asked Beckwith Sr. how he could already know about her stepson’s death. He replied that “news travels.”

In Texas, solicitation on the part of funeral directors can be illegal; in 1991, the commission said it received one allegation of solicitation by Golden Gate each month. “They’re fighting over bodies in Dallas,” Texas Funeral Service Commission executive director Larry Farrow told the paper. “We get more complaints from the Dallas-Fort Worth area than anywhere else in the state.” (Beckwith Sr. denied all wrongdoing.)

Golden Gate dropped out of the headlines for another decade—save for a splashy $6,000 fine the commission levied in 2003 for hiring an unlicensed embalmer. But the complaints never stopped, says Jim Bates, who has for more than 30 years worked with the Funeral Consumers Alliance of North Texas, a local arm of the national nonprofit watchdog organization. In years past, Bates would spend hours poring over documents in the Texas Funeral Service Commission’s Austin office. “I didn’t take a log or write it down, but I just kept seeing Golden Gate, Golden Gate,” says Bates, who will serve as an expert witness for Webster, Palmer, and other plaintiffs. “That just stuck out in my mind.” When he heard the latest allegations against the company, Bates said they were “no surprise at all.”

It’s clear that Jackie Carlisle doesn’t want to tell the story again. It’s painful and tedious. It takes time away from her work as a nursing assistant and from raising her younger brother. She’s always being called to her lawyer’s office to talk through the case again for the lawsuit or a prying reporter like me. But the 33-year-old feels this is part of her path to justice, and so Carlisle goes back to the beginning once more.

In May 2020, as the pandemic swept into North Texas like so many spring thunderstorms, Carlisle’s mother, Jennifer Hall, was hospitalized. Doctors intubated her in hopes of saving her life, but Hall died of complications from COVID-19 a month later. She was 48.

The loss has been difficult for Carlisle to process, and not just because it happened at a distance. Carlisle’s mother had her young and raised her on her own. “That was more like my best friend and my mom,” Carlisle says. But there wasn’t time to grieve. The hospital rushed Carlisle to find a funeral home to claim her mother’s body, and when an aunt recommended Golden Gate, Carlisle didn’t hesitate to call.

In her meeting with Golden Gate staff, Carlisle arranged for standard embalming and cosmetology for Hall, as well as transportation of the casket to a wake and funeral at Cornerstone Baptist Church and later Lincoln Cemetery. The next weekend—incidentally, the 155th anniversary of Juneteenth, where the last enslaved people in Texas were finally freed at the end of the Civil War—Carlisle would be able to see her mother again, if only for a few days.

But the morning of the viewing, Golden Gate presented Carlisle with a body that wasn’t her mother’s. It took staff over an hour to find Hall’s actual remains. When they finally presented Hall’s body, she was still in her hospital gown, with no makeup or hairstyling. Her skin was splotchy and her stomach bloated—evidence, Carlisle’s lawyers say, that Hall’s body was decomposing and likely not stored or embalmed properly.

Shocked by the state of her mother’s body, Carlisle passed out. “Mind you, I haven’t seen her within a month, so when I did see her, I just wasn’t pleased at all,” Carlisle says, her big, blue eyes gone cold. “I wasn’t pleased with the smell, the way she looks—everything, everything was bad.”

When Carlisle regained consciousness, she decided to prepare the body herself. She and her family members pulled out the makeup they had in their purses and tried to touch up Hall’s face. They spritzed her body and casket with the perfume they had on hand, a futile attempt to cover up the stench. The chaos delayed the wake, and when they finally arrived at the church, people were so aghast that they took pictures of Hall’s body on their phones. “My feelings were just hurt,” Carlisle says. “I mean, nobody from Golden Gate was there to say anything comforting?”

Carlisle’s complaints continued to pile up. Her mother’s obituary was full of typos. Golden Gate had tried to hold the wake in their own chapel, despite explicit instructions to transfer the body to Cornerstone. Perhaps the most painful thing for Carlisle was watching her younger brother struggle with everything he’d seen. Within a few days, she was looking for a lawyer.

While the Texas Funeral Service Commission has at times intervened in funeral directors’ unscrupulous behavior, it’s just as often part of the problem, according to several sources familiar with the agency. “The Texas Funeral Service Commission is useless as far as I’ve seen,” says Dallas lawyer John Howie Jr., whose decadelong legal tussle with Service Corporation International convinced the Supreme Court of Texas that negligence in the funeral industry qualifies as a form of mental anguish—and made the current lawsuits against Golden Gate possible.

The commission does not exercise its regulatory powers as often or forcefully as critics would like, which include the ability to investigate funeral service establishments, raise fines, and even revoke licenses. In the last five years, the commission has received on average 200 complaints annually, according to executive director Glenn Bower. For an undisclosed number, these do result in fines, which can range from $250 to $5,000, according to a publicly available penalty matrix. But in the two years that Bower has served as executive director, he tells me they have yet to revoke a license.

The commission’s previous transparency has also been further undone by its most recent sunset review, a routine process in which the Legislature decides whether an agency should continue as is, be consolidated, or be abolished—and whether its occupational codes should be revised. In its latest review, which ended in 2019, the Texas Funeral Service Commission endured but changed Texas Occ. Code 651.2035 to make it difficult for the public to access documents related to investigations of funeral homes, even as the commission publishes some funeral home violations on its website.

The consequences were swift. Bates is no longer able to visit the archives at the Austin office. All of my requests for documents related to Golden Gate and the Beckwiths were denied. Even families like the Palmers who have filed complaints with the commission have not received detailed information on the outcome of the investigations they launched. Sellers, the Palmer family’s attorney, says for each case closed, he receives only a cover sheet stating whether a penalty was enforced—but no additional details, including the size of the penalty. Now, more than ever, “there is very little will in the funeral service commission,” Bates says.

There are many possible explanations for the Texas Funeral Service Commissions’ sunset review reformulation, but Bates and Howie suspect the financial influence of the industry is the root of the problem. The Houston-based Service Corporation International, the largest funeral service provider in the United States, is one of several such political donors. The company has donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to the campaigns of former Gov. Rick Perry, current Gov. Greg Abbott, former President George W. Bush, and numerous other Texas politicians. And the relationships run deep. Until the late 1980s, the Texas Funeral Service Commission and Service Corporation International shared both office space and a lawyer.

The result, critics argue, is a regulatory environment that is too friendly to funeral homes, which may lead some undertakers to feel they can operate with impunity. While there are many reputable funeral service providers throughout Texas, the industry has often operated on a “don’t ask, don’t tell strategy,” says Wilson Knight, a former death care worker now earning his Ph.D. in rhetoric at Texas Tech University. When coupled with the American public’s general unwillingness to confront death, concealment can become the default—until someone comes along to challenge the status quo.

When it comes to the current allegations against Golden Gate, what happens next is anyone’s guess. As the lawsuits inch along, so, too, will legal discovery, which could reveal new information about what goes on behind closed doors. But these cases will take years to resolve. In the meantime, the families suing will struggle to heal.

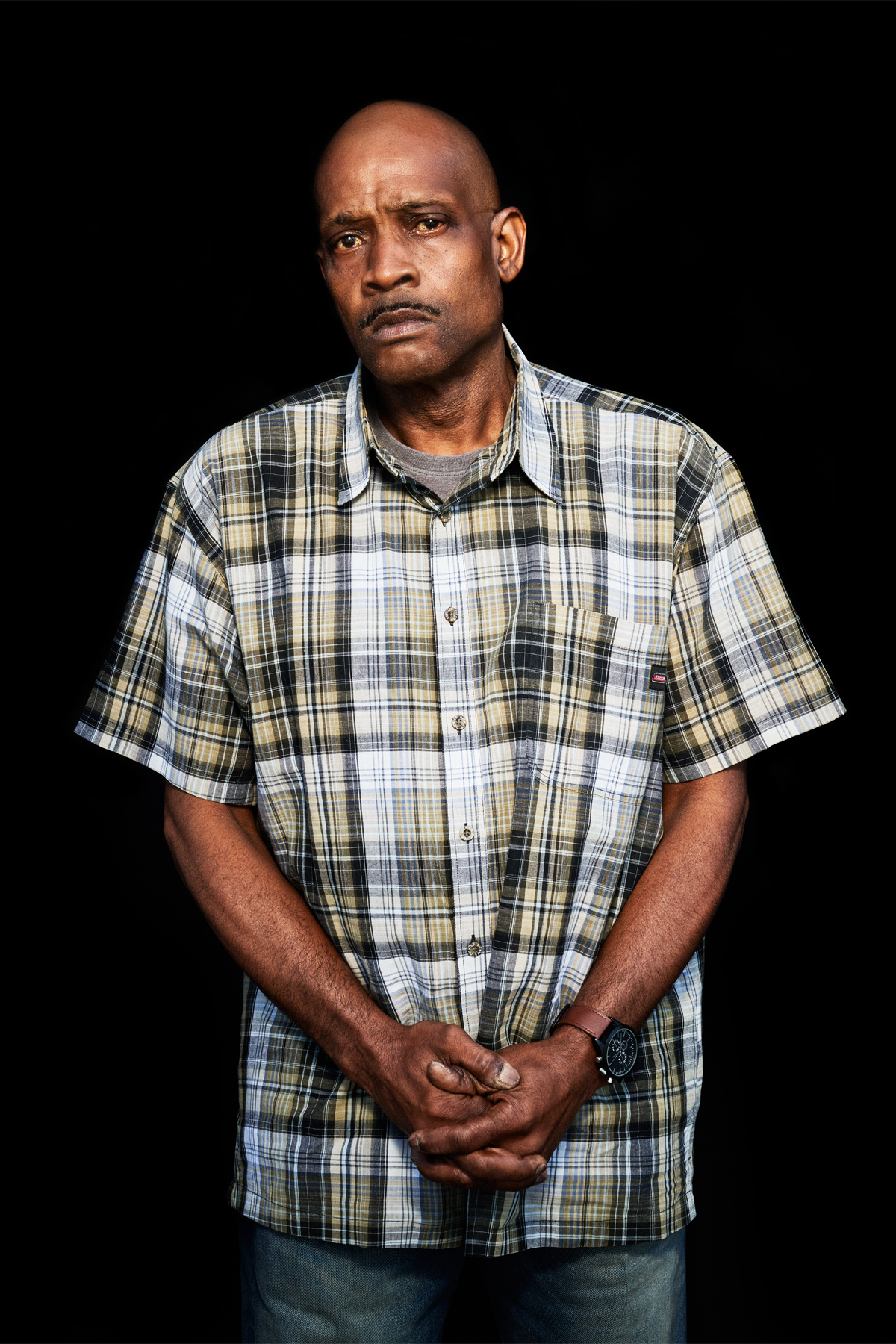

On a sunny afternoon, I meet Robert Jinks and Ryan Sellers, also serving as his lawyer, for an interview on a breezy patio. Jinks, a tall, slender man in his 50s, tells me he never thought he’d be the last member of his family standing. His brother died first, then his mother, and then, in January 2021, his father, Johnny Ray. That night, Jinks got a call. Something had happened to his father. When he arrived at his father’s house, paramedics were working away on the old man’s chest, trying and failing to revive him.

When doctors later declared Johnny Ray dead, Jinks asked Golden Gate to recover his body from the medical examiner’s office. Golden Gate picked up his body the next day but told Jinks more than once that they didn’t have the proper paperwork to proceed. When Jinks repeatedly called the medical examiner, he was told everything on their end had been wrapped up; the funeral home should be good to go. Days passed before Golden Gate finally said they were ready to move forward.

Confused, Jinks arranged to stop by the Dallas location and spend some time with his father’s body before the funeral. When he arrived, it took more than an hour for the funeral home to identify the body. When they presented Jinks to his father, one of Johnny Ray’s eyes had been smashed in. He also had signs of freezer burn, from his skin to the frost on his eyebrows; funeral home practice typically involves refrigerating, but not freezing human remains. When Jinks asked for an explanation, a staff member turned away from him, as if she couldn’t hear him. She “didn’t say a word,” he says.

Jinks still doesn’t know where his father’s body was kept or what happened to his face. Since the incident, Jinks has lost over 20 pounds. He had to move out of his room with his wife, because he can’t sleep at night. He’s on antidepressants and in counseling, but he can’t stop turning the questions over in his mind. If it weren’t for his wife of 34 years, “I would have killed myself by now,” he tells me. “I really would have committed suicide.”

Other families can likely relate. While Jinks was the only one who shared suicidal thoughts with me, Webster and Palmer both volunteered that they are in therapy for the first time. “I’m taking three prescriptions a day just to be mentally stable,” Palmer says, “just to sit here and have this conversation with you and not be bawling in tears.”

Going forward, everyone has different hopes. One family I spoke to explicitly said they don’t want Golden Gate to go out of business, given its important role in the Black community. Others want to see the entire operation closed for good.

Similarly, some want to get their compensation and move on, while others want more than anything an explanation of what really happened. But however they define it, a sense that justice is served is paramount to all—as is a guarantee this will never happen to anyone else.

That might be the hardest assurance to get. “We all speed sometimes, and we get a ticket,” says Bates, of the North Texas Funeral Consumer Alliance. “But Golden Gate is just speeding all the time, throwing tickets out the window.”