Around 10 pm on a Thursday in mid-April, Esther Kim Varet ordered roughly 40 tequila shots. She held her shot in one hand, a lime in the other, and stood in front of a dark velvet curtain in Sassetta, an Italian restaurant that had yet to officially open in the Joule hotel. She was making a toast to the newest location of her trendsetting gallery, Various Small Fires, but also to her hometown.

Dallas has changed a lot since Kim Varet, a Trinity Christian Academy alum, grew up here in the ’90s. To have a career in the arts, she had to leave, first for New York City, where she ran a gallery in the 2000s, and then to Los Angeles, where she started the successful VSF. But here she was, back in Dallas, where the city’s art scene is showing signs that it is coming of age.

Kim Varet has a keen understanding of the art market. In 2019, she opened VSF’s second location in Seoul alongside blue-chip galleries such as Lehmann Maupin, Pace, and Perrotin. And this year, she opened in the Joule-adjacent space that once housed the boutique Ten Over Six. This is just one of many indications that art dealers from major coastal markets are beginning to take this city—its artists, its patrons, its collectors—seriously.

The invited guests on this particular evening included a few dozen curators, socialites, collectors, benefactors, exhibiting artists, and press. Everybody I talked to that evening was buzzing about this new gallery and the next week’s Dallas Art Fair—but also, if not especially, a tidbit of industry gossip a local writer had published on his blog that day.

Was it true, people were asking, that Gavin Delahunty was going to be the new curator at the Dallas Contemporary? Who could possibly think that was a good idea?

Before we answer that question, let’s back up.

In Dallas, there are three major museums. There are other art museums in North Texas, even some in Dallas, but the big three, at least for the scope of this story, are the Nasher Sculpture Center, the Dallas Contemporary, and the Dallas Museum of Art. These are the institutions shaping the future of art in Dallas.

The Nasher Sculpture Center is a relatively smaller museum focused on a specific medium: three-dimensional artwork. This museum houses the collection of Patsy and Raymond Nasher and brings in exhibitions dedicated to presenting new ways to think about what counts as sculpture. It’s mostly irrelevant for this story.

The Dallas Contemporary occupies a huge warehouse space in the Design District. It was created in the late ’70s to be the city’s kunsthalle, a noncollecting museum with anywhere from two to five exhibitions at a time. The Contemporary is focused on introducing visitors to art of the moment.

Finally, there is the Dallas Museum of Art. It is an encyclopedic museum dedicated to amassing a collection of work that ranges from ancient to contemporary art, with an eye toward academic scholarship and preservation. It’s where you go if you want to learn some art history. It’s also the place to see major touring exhibitions. It’s our Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In early 2014, the Dallas Museum of Art hired an Irish curator with a promising track record to be the Hoffman Family Senior Curator of Contemporary Art. Gavin Delahunty entered the Dallas art scene with the same authority he entered most rooms. When he was leading tours of exhibitions or shaking hands with donors at galas, he had a commanding presence.

It’s not that he’s conventionally handsome. He has cropped, ginger hair and sometimes grows a beard that is just as red. His muddy blue eyes have an avian quality, and his brow seems eternally locked in a menacing glare. When he smiles for a photo, which he rarely does, it looks unnatural. And yet, when he spoke about art in his Irish brogue, people listened.

Coming from the Tate Liverpool, where he had been the head of exhibitions and displays since 2010, Delahunty was a big get for the North Texas museum. Before that, he was the curator of the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art for three years. He was bringing with him from the U.K. a reputation for curating a spectrum of contemporary work by canonical artists, such as Ellsworth Kelly and Felix Gonzalez-Torres, while keeping an eye on important artists working today, such as Charline von Heyl and Bonnie Camplin.

“Gavin shares the DMA’s vision for the important role that contemporary art plays in broadening our community’s understanding of the global art world,” said Max Anderson, the museum’s executive director at the time, in a press release.

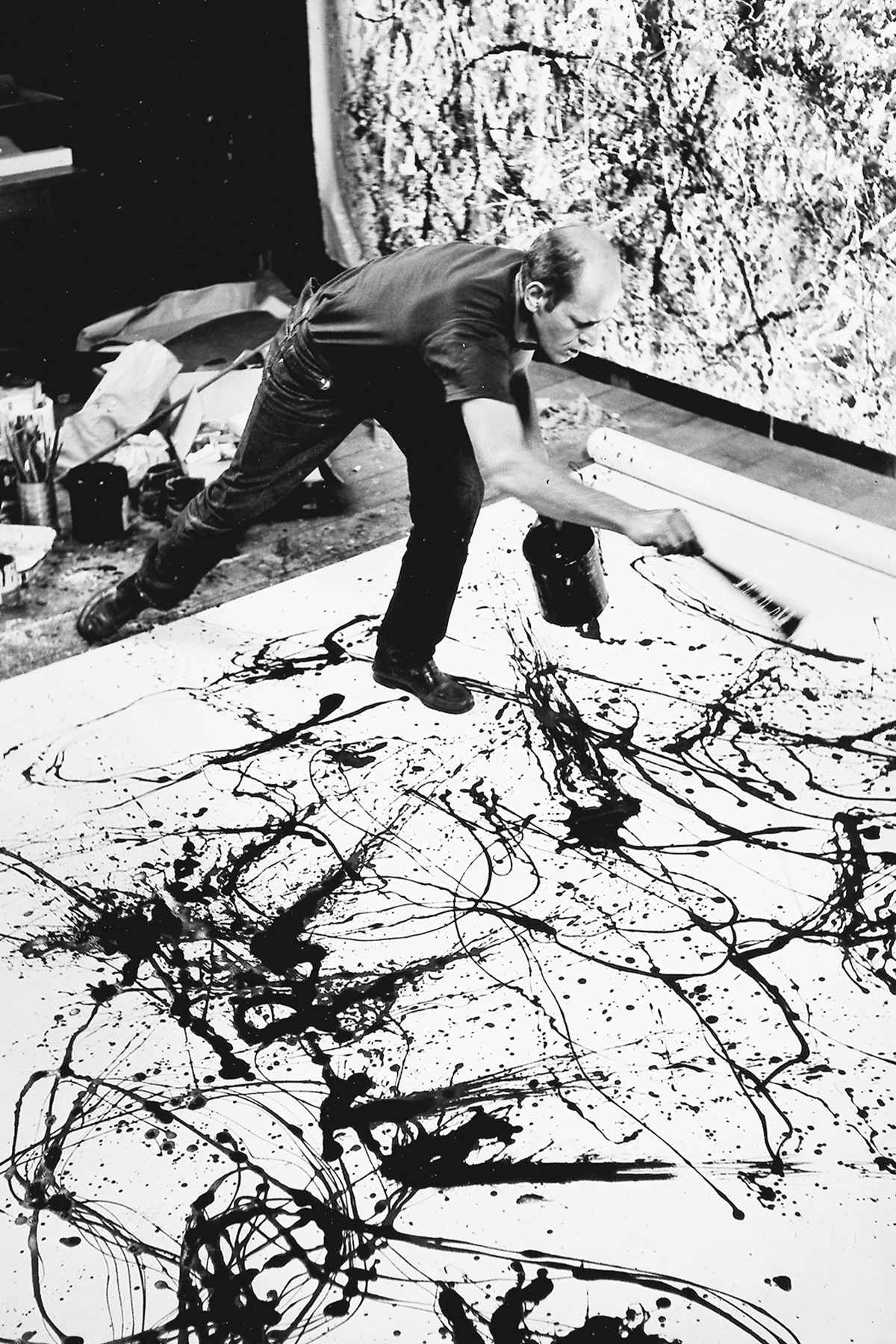

The first exhibition Delahunty brought to the DMA was a showstopper. “Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots” focused on the lesser-known black enamel paintings by the abstract expressionist famous for his gestural, sometimes violently colorful drip paintings. The exhibition received critical acclaim first at the Tate Liverpool, where it opened in the summer of 2015, and then at the DMA, when it opened in the fall.

Delahunty’s arrival in Dallas was so heralded one had to wonder: why would a curator on the rise leave the Tate for the DMA? The Tate, a collection of four museums, including the country’s national collection of art, is the premier art institution in the U.K.

Maybe it was for the money? According to public filings, Delahunty’s annual salary from the DMA alone was around $140,000. That’s only a few thousand dollars less than the head of one of the Tate’s museums (at least as reported by the Times of London in November 2017). It’s likely Delahunty was making substantially less in his role as head of exhibitions and displays.

Maybe it was a step up? Although moving from the Tate Liverpool to the Tate Modern or Tate Britain would have been a better career move, earning a senior curator position at a major American museum was undeniably a promotion.

Whatever the reason, former employees say many at the Tate Liverpool were glad to see him go. “Nobody could stand him by the end. He had the reputation for being ‘my way or the highway,’ ” says Sivan Amar, who worked for Delahunty as the registrar in the exhibitions and displays department from 2012 to 2015, handling logistics among other duties. “Frankly, he was a pompous asshole.”

Amar says he didn’t fit the museum culture, which was open and collaborative. Delahunty was known for dismissing his staff’s input or not even showing up for what were meant to be mandatory meetings with his team. She describes his treatment of interns as dehumanizing. He would refuse to learn their names, instead referring to them as serial numbers. Amar’s account of Delahunty was confirmed by other museum employees. (Delahunty did not return several requests for comment.)

In 2015, Amar was part of the team that couriered the artwork for the Jackson Pollock exhibition to Dallas. That was the last time she interacted with Delahunty. Although she never witnessed any sexual misconduct in the U.K., when she saw the news of his departure from the DMA, she wasn’t surprised.

“I had heard rumors of flirting and him making people feel uncomfortable, but the U.K. is a stricter and better culture for workers overall,” Amar says. “I think he got to America, and it was like the Wild West.”

By the time the Jackson Pollock exhibition opened in the fall of 2015, Delahunty was climbing his way to the top of the Dallas art scene. In addition to his job at the museum, he was hired to curate the Karpidas Collection, a new space that opened on Hi Line Drive in 2015 dedicated to one of the more interesting private collections in the city, a wide-ranging assemblage with more than 1,000 works. The woman who hired him for the job was Elisabeth Karpidas, a board member at the DMA. The first exhibition he curated there was titled “Empathy and Love”—words that might seem ironic a few short years later.

Meanwhile, his wife, Anna Lovatt, with whom he has two sons, was establishing herself as a beloved art history professor at SMU. She later earned tenure there, in 2021, and her students, who range from undergraduates to Ph.D. candidates, praise her professionalism and mentorship.

Life for Delahunty was great in the public eye. But in the whisper network, stories of his aggression, drunkenness, and sexual misconduct were starting to be shared more loudly. By 2017, in the wake of the #MeToo movement, these stories reached his employers. That year, on November 18, the DMA announced Delahunty’s resignation with a statement he wrote himself, which acknowledged that he was “aware of allegations regarding my inappropriate behavior.”

Five days before Delahunty resigned from the DMA, an editorial by New York-based painter Natalie Frank had run on the website for ARTnews, one of the most prominent national art industry publications. Titled “For Women Artists, the Art World Can Be a Minefield,” the first-person account chronicled a series of untoward sexual advances, comments, and actions that had been directed at Frank by powerful critics, gallerists, and, in one case, a “curator from a powerful institution.”

She described meeting the unnamed curator for a drink after “a studio visit during which he dangled offers of acquisition, collector support, and introductions.” She says while she drank sparkling water, he drank a bottle of wine. When his conversation grew lewd, she called it a night. But after she left, he continued to text her, inviting her to spend the night with him. When she refused, he responded, “Grrrrrrr!” She never heard from him again.

Although she didn’t identify the curator in the piece, she wrote that his reputation preceded him to such an extent she had heard his name prefaced with “Grabbin’.” At the time, many people in the Dallas art scene couldn’t help but note the rhyme the moniker made when paired up with Delahunty’s name: “Grabbin’ Gavin.”

I told a few people, and they told me to keep my mouth shut because he was so powerful.

Natalie Frank

When I emailed Frank in April with the news that Delahunty might once again be appointed to a high-profile curator position in Dallas, she immediately called me. She was appalled.

Frank says she met Delahunty when she walked a group of curators through her solo exhibition “The Brothers Grimm” at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, in the summer of 2015. In early 2017, he visited her studio in New York, where, she says, he made promises of potential acquisitions and introductions. Then they met for a drink at the Maritime Hotel bar. That was when things turned sexual.

When she arrived, he insisted she meet him at his room. She says she stood in the hallway until they walked down to the bar together. When the bar closed, they moved to the lobby, where he traced an outline of male genitalia in the marble of the fireplace. At that point, she says, she excused herself. When she got in a cab to go home, he texted, “You should’ve stayed.” She responded with a question mark. “You should’ve stayed here with me,” he typed. And then: “Grrrrrrr!”

“I told a few people, and they told me to keep my mouth shut because he was so powerful,” Frank says. “I started to ask around, and when I learned this was widespread behavior and that he had threatened assault on another woman, I decided to write the piece for ARTnews.”

What happened to Frank was hardly an isolated incident. Sources tell me that by early 2017, his reputation was such common knowledge that there was only one DMA employee still willing to work with him on exhibitions. He was notorious for being “handsy.” When he was installing exhibitions and wanted one of the women helping him to move from one vantage point to another, he would grip them at the waist and walk them from behind to the new location.

Much of his behavior seemed to be linked to alcohol consumption. A source said he would take “celebratory” tequila shots in the museum midafternoon. There are numerous accounts of late-night texts asking younger, lower-level female employees to come out drinking with him. Others describe holiday parties where he would imbibe and then ask young women to come home with him.

After receiving a series of complaints, the volume of which was characterized to me by one source as “a file a mile deep,” the DMA had its law firm, Locke Lord, open an investigation to determine the extent of Delahunty’s behavior. Based on emails I’ve seen, sent by Frank and other complainants to high-level DMA employees, the catalog of alleged acts committed by Delahunty ranged from inappropriate comments to inappropriate touching to, in one case, a threat of sexual assault. In one instance, Delahunty told a museum employee, whom he allegedly had already groped, that he wanted to grab her genitals and “hit [her] in the face.” (In an email I’ve seen from this woman to a high-ranking DMA staffer, she reiterates her complaint and says she discussed it with board president Walter Elcock.)

I’ve heard numerous firsthand and secondhand accounts of Delahunty making advances, verbal and physical, on subordinate employees in private meetings both inside and outside of the museum. In addition, according to a number of sources, these acts had also been perpetrated on the wives of board members at public events. Sources say he walked up to the wife of a board member and kissed her on the neck just feet from her husband. Sources also say he approached another board member’s wife who was pregnant and told her to make sure she sat with her legs uncrossed.

When initial complaints were made by employees about what had taken place, at least one of these women says she was told by a board member to either seek therapy or work remotely if she felt uncomfortable. In another email I have read, when an employee of the DMA filed a complaint alleging Delahunty had solicited her, his assistant purportedly told the complainant she “took one for the team,” and that she should be flattered he was attracted to her because it meant she wasn’t a “gutter slut.” The assistant did not return several requests for comment.

I’m told some board members did take these complaints seriously. Among them were Elisabeth Karpidas and Catherine Rose, who took part in a call with the museum director, Agustín Arteaga, just days before Delahunty resigned.

Arteaga arrived at the museum in the summer of 2016, 10 months after Maxwell Anderson had abruptly left the position. D Magazine’s Peter Simek reported in 2015 that under Anderson’s leadership, “There were stories of infighting, scapegoating, back-stabbing, backroom power plays, and a looming board revolt.” The museum refused to answer any questions about Anderson’s removal.

When Delahunty resigned in 2017, Anderson told ARTnews: “In the end, we are all responsible for our personal conduct, as he has apparently accepted, and now has to address appropriately.” Once again, the museum offered no official comment.

Arteaga issued this statement in response to an interview request: “The DMA is committed to maintaining a work environment that is free of harassment of any kind and will not tolerate harassment of its employees by anyone. It is our policy to take appropriate and timely action when concerns are brought to management.”

After the initial media blitz about his abrupt departure from the DMA, Delahunty’s name wouldn’t be seen in print for almost two years.

Then, in February 2020, he resurfaced as the curator of an exhibition at The Warehouse, a space in North Dallas dedicated to the art collection of Cindy and Howard Rachofsky. That exhibition, “Psychic Wounds: On Art & Trauma,” was originally scheduled through November 2020, but, due to the pandemic, it remained on display until fall 2021.

For many people in Dallas and beyond, this employment came as a surprise. Cindy sits on the board of trustees of the DMA, and I have documents that show Howard had been made aware of the specific details of the allegations by one of the accusers. And yet here was Delahunty curating a show about trauma.

The Rachofskys exist somewhere near the nucleus of Dallas art. In 2021, ARTnews ranked them as one of the 200 most important art collectors in the world. Their collection of more than 800 works of art includes pieces by Donald Judd, Julian Schnabel, and Robert Ryman.

“[Howard] didn’t want to have children grow up in Dallas and have to go out of town to see great contemporary art, like he had to do,” John Sughrue, the co-founder of the Dallas Art Fair, told Artsy.com in 2018. “He’s a champion, and he’s a community leader.”

To the Dallas art scene, the Rachofskys matter. The couple hosts the annual TWO x TWO art auction fundraiser, which is a who’s-who of the national arts scene and benefits both amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research, and the DMA. In 2005, the couple donated the entirety of their collection to the DMA. When Sughrue was thinking about starting an art fair here, he called Howard. (“He counseled caution,” Sughrue told Artsy.com.)

When the Rachofskys employ someone—for example, Delahunty—it serves as an anointment. In this case, it caught the eye of the Dallas Contemporary, an institution on the hunt for some fresh blood. It also happens to be an institution for which Sughrue serves as the president of the board of directors.

In the fall of 2021, Dallas Contemporary’s executive director, Peter Doroshenko, was nearing the end of his contract. There were plenty of reasons for the board to renew it. In 2010, Doroshenko came to Dallas from Europe, a short, soft-spoken man with a slick bald head and a sharp, almost alien gaze. He was familiar with Texas, having worked at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston in the early ’90s. But he had most recently worked in museums in England and his native Ukraine, for which he served as commissioner for the country’s pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2007, 2009, and 2017.

He was handed a monumental task at the Dallas Contemporary. Succeeding longtime figurehead Joan Davidow as the museum’s director, he inherited an institution struggling to find a foothold in the community, not to mention a brand-new, 37,000-square-foot space.

Doroshenko told D Magazine at the time that he saw the Contemporary as an “anti-museum.” He was determined to build upon Davidow’s legacy of taking risks. During his nearly 12-year tenure, he did just that, elevating the museum’s reputation as a place for serious art, drawing international attention for progressive, challenging exhibitions.

“He is an exceptional curator, and he brought to our city really interesting work by important artists,” says John Pomara, an artist and former board member of the Contemporary. “Peter really elevated the reputation of Dallas in the global art conversation.”

But there were also plenty of reasons for the board not to renew his contract. On his watch, the Contemporary made a series of blunders. In 2013, the museum sold donated works by local artists on eBay for close to 1 percent of their market value, which Doroshenko at the time chalked up to a “stupid mistake,” shifting blame to his employees.

There are allegations of unpaid vendors, exhibition works that went unreturned for months, and at least one mismanaged donation. Former employees say millions of dollars of artwork has been damaged while on display in the museum. These damages, they say, have made it next to impossible for the museum to secure art insurance for its shows.

The museum also struggled with its reputation in the art community. In summer of 2015, Doroshenko acknowledged to D Magazine, “People say we’re a boy’s club.” At the time, the Contemporary had a reputation for exclusively featuring the works of male artists, often with hypermasculine subject matter or personas, including exhibitions by Nate Lowman, David Salle, and Loris Gréaud in 2015 alone.

That same year, Doroshenko made a savvy hire in Justine Ludwig, who helped the Contemporary find good standing in the local community. Ludwig is a stylish, petite woman with a speckled pixie cut, who could wander comfortably from an underground punk rock show into a high-dollar gala. As senior curator, she programmed impressive shows, sustained a national presence as a writer and tastemaker, and worked closely with Dallas-based artists. She brought in work by important contemporary artists, mostly female, including Paola Pivi, Nadia Kaabi-Linke, and Pia Camil. When Ludwig left in 2018, the museum floundered.

In 2019, it made two hires. First was Carolina Alvarez-Mathies, a dazzling El Salvadorian woman who attended TCU and then worked in communications for museums and nonprofits in New York. She’s been described as the “Paris Hilton of El Salvador,” which is shorthand for her hybridity as a model, heiress, socialite, and professional. In her role as deputy director, she would oversee fundraising and marketing.

To replace Ludwig as curator, the museum hired Laurie Ann Farrell, who came from a post as a curator of contemporary art at the Detroit Institute of Art. By the end of 2020, both Farrell and the museum’s director of learning, Angela Hall, had quietly left.

In the fall of 2021, the board’s executive committee, led by Sughrue, met with Doroshenko to outline their goals for the museum, the primary one being fundraising. His contract was expiring.

During his time at the museum, Doroshenko had raised the budget fivefold, although public filings tell a story of financial instability. In 2019, the museum ended the year with a nearly half-million-dollar deficit; in 2020, the museum ended the fiscal year in the black by a little more than $16,000. This was thanks in no small part to Alvarez-Mathies’ idea to launch an online shop that, she told the Dallas Morning News, earned $1 million in revenue in 2020 alone. Now the board wanted to grow the 2022 budget by more than $1 million, and they didn’t believe Doroshenko could do it.

The executive committee announced to the board in October that Doroshenko would be vacating the post effective the end of May 2022. They took a vote, but, according to board members, it appeared to already be a done deal. Doroshenko assumed the role as director of the Ukrainian Museum in New York City this summer.

In March, the museum announced Alvarez-Mathies would take over as executive director—the first woman of color to run a major museum in North Texas. Because she has no significant curatorial experience, someone would have to be brought in to manage that side of things. Enter Delahunty. Well, almost.

As early as summer 2021, a Contemporary board member was surveying members of the Dallas art community with the question: “What do you think about Gavin Delahunty as a curator?”

Geoff Green, a partner at a private equity firm, appeared to be on a scouting mission, determined to gauge whether or not the decision to hire Delahunty would be accepted. The answers to his query, at least the ones relayed to me, were all some version of: “He’s a great curator, but … ” I’ve been told Green did not seem interested in hearing the end of the sentence.

By all appearances, access to Delahunty would mean access to the Rachofskys and Marguerite Hoffman, another important, monied art collector for whom he continued to work. Delahunty edited a book about the Hoffman art collection, Amor Mundi: The Collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman, which was published in February. Access to these collectors might, in theory, mean access to their money.

It would be a savvy business move, and Sughrue is nothing if not a shrewd businessman. A Massachusetts native and Harvard graduate, Sughrue came to Dallas via Wall Street in 1990, at a time when the city’s real estate market was particularly depressed. Since joining the investment firm Brook Partners, he has found himself at the intersection of art and commerce. In addition to co-founding and managing the Dallas Art Fair, he is the real estate developer behind Museum Tower, which, upon completion in 2013, became a source of controversy because of the intense glare it cast into the Nasher Sculpture Center’s garden and building. He is also the developer of a strip mall in the Design District called River Bend, which is now the landlord for multiple galleries, including 12.26, Erin Cluley Gallery, and Photographs Do Not Bend.

“How are all of these things not conflicts of interest for [the Contemporary]?” one source asked of Sughrue’s stakes.

By April, sources say, the parameters of a deal with Delahunty had been drafted. In summer of 2022, he would come on board as a curatorial consultant. He wouldn’t be in a public-facing role; instead he would serve as a sort of “shadow figure,” as one source described it, working behind the scenes to bring in international curators or line up big-name art shows. Alvarez-Mathies would handle the day-to-day operations, and Delahunty would help guide the museum’s artistic vision. According to sources, this deal was brokered without the knowledge or consent of the larger board.

When the local writer Darryl Ratcliff published a blog post titled “Is Delahunty the new curator at the Dallas Contemporary?” on his Substack on April 14, he was reporting on what he calls a well-sourced rumor.

“I am routinely in contact with people at all of our large institutions,” Ratcliff says. “I started to hear things at the start of the year that this was taking place, and by mid-March I was told it was a done deal.”

Ratcliff’s article set off a chain of events. Reporters from ARTnews called Alvarez-Mathies directly, looking to confirm the rumor. Within days, sources say, Delahunty had stepped away from the contract. The Contemporary responded to ARTnews the following Tuesday, saying that they were “not working with him in any capacity.”

I had also started making calls, and I can’t help but wonder what would have happened if Ratcliff, ARTnews, and I hadn’t moved quickly. Would Delahunty be working behind the scenes to program exhibitions, hire curators, and bring in artists at the Contemporary? Would Alvarez-Mathies be forced to explain away his presence? What kind of “inappropriate behavior” did the executive committee think caused Delahunty to leave the DMA? Did they think he left the museum for a few bad jokes? Did they think our collective memory had lapsed? Did they think we wouldn’t care?

By the time the VIP preview of the Dallas Art Fair rolled around a week later, the chatter about Delahunty had mostly digressed during the Champagne-soaked strolls through the gallery booths. The rumor mill was churning out new topics: was the art at the fair particularly decorative, which is to say boring, this year? And wasn’t it strange that Virgin Hotels co-owner Bill Hutchinson was there, given his legal troubles?

At the Fair’s closing party, which transformed Tony Tasset’s giant eyeball sculpture in downtown into the hub of an elaborate apocalyptic bunker, one local curator was approached by one of the Contemporary’s board members asking if he was interested in working with the museum. The curator says the conversation was booze-fueled and brief, but the search for a curator had clearly been reopened.

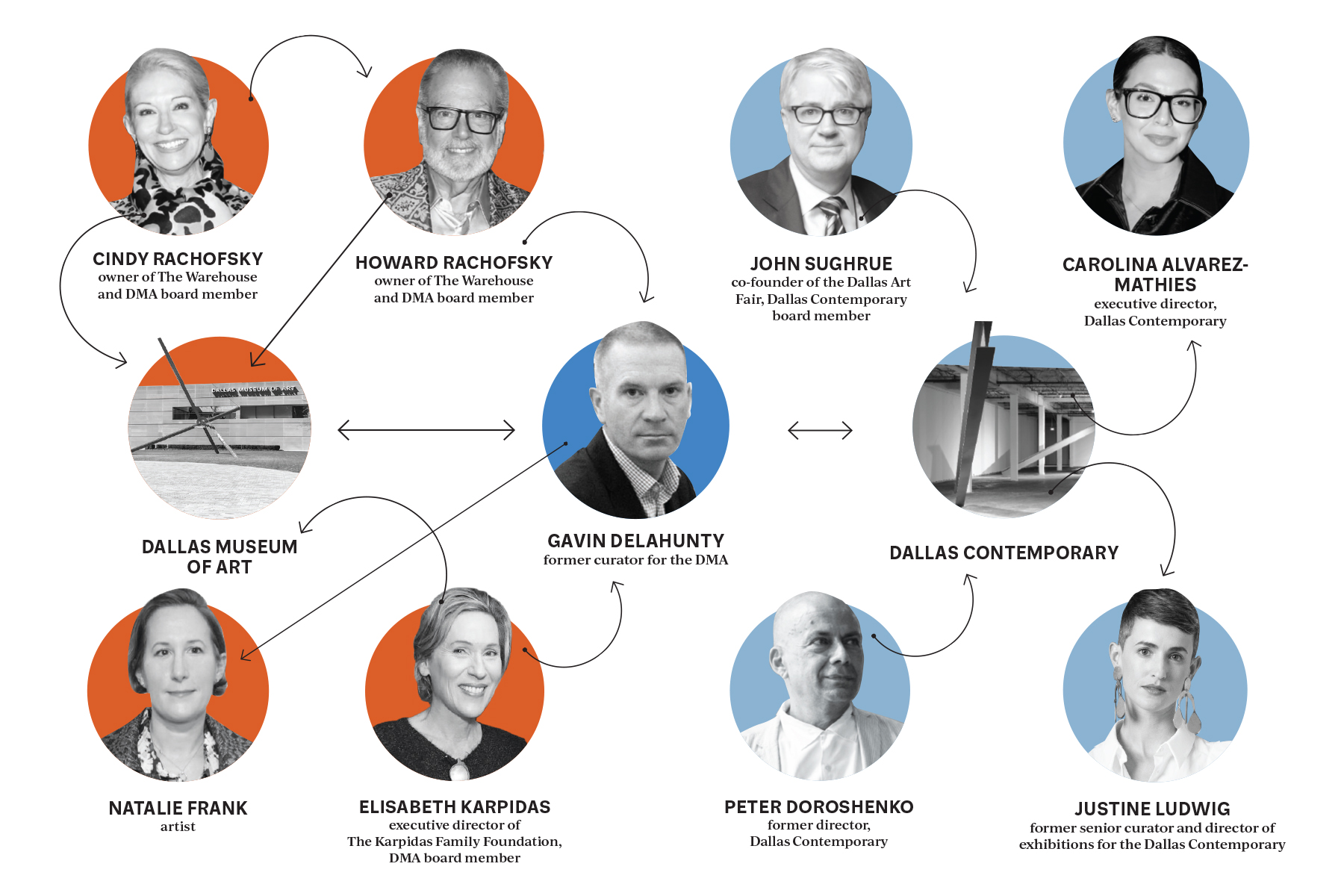

Art and Commerce

In Dallas, money and the major institutions go hand in hand. Here is a look at how they came together around Delahunty.

In response to a request for an interview with Sughrue or Alvarez-Mathies, the Contemporary’s public relations firm issued this statement: “Dallas Contemporary continues to have conversations with a multitude of artists and curators to partner and collaborate with the museum, with Carolina Alvarez-Mathies recently stepping into the role of executive director as of May 2022. To date, the museum has not hired a new curator or any consultants.”

The linguistic gymnastics in the statement are interesting, resetting the clock to May, which allows Delahunty to be a blip in the museum’s rearview mirror.

The impact of Delahunty’s behavior, whether it be categorized as sexual misconduct or a hostile work environment, remains hard to quantify. Many women were scared to share their stories because of the rich, powerful people who have continued to employ him—the very people who brought him into this community in the first place. Others were impossible to track down because when they left the DMA, they moved away from Dallas or stopped working in art entirely.

“People like Gavin are the reason I don’t work in the art world anymore,” says Amar, who moved from the Tate Liverpool to New York galleries and eventually Sotheby’s, which she left in 2019. “In my experience, he’s far from the only one.”

Perhaps Delahunty just fits a cliché: power corrupts. The painter Katy Moran, whose solo exhibition he curated at the MIMA in 2008, says both she and the staff at the gallery enjoyed working with Delahunty. It seems it wasn’t until he arrived at the Tate that he became difficult to work with and not until the DMA that the allegations attached to him became more serious.

The redemptive arc being offered by board members of the Contemporary on behalf of Delahunty is simple: he had a drinking problem. He sought help. He is better now. Because there had been no public account of his misdeeds, there was plausible deniability. He hadn’t gone to jail. What could he possibly have done that was so bad?

But Ratcliff says that’s the wrong question.

“Here’s a case where people did share their stories and there was some sort of change that happened, only for it to be walked back in the same city where it happened,” Ratcliff says. “And without in my mind a real true accounting, a true reconciliation process.”

Perhaps the larger question isn’t merely about Delahunty. Perhaps it’s this: what do we want our art scene to look like? What people and what institutions are responsible for safeguarding any given community in a city? What kind of transparency should citizens demand from their institutions?

“In situations like this, it’s not just one bad actor,” Frank says. “It’s the institutions who time and again cover up what happened.”

This story originally appeared in the August issue of D Magazine with the title, “Do Not Touch.” Write to [email protected].