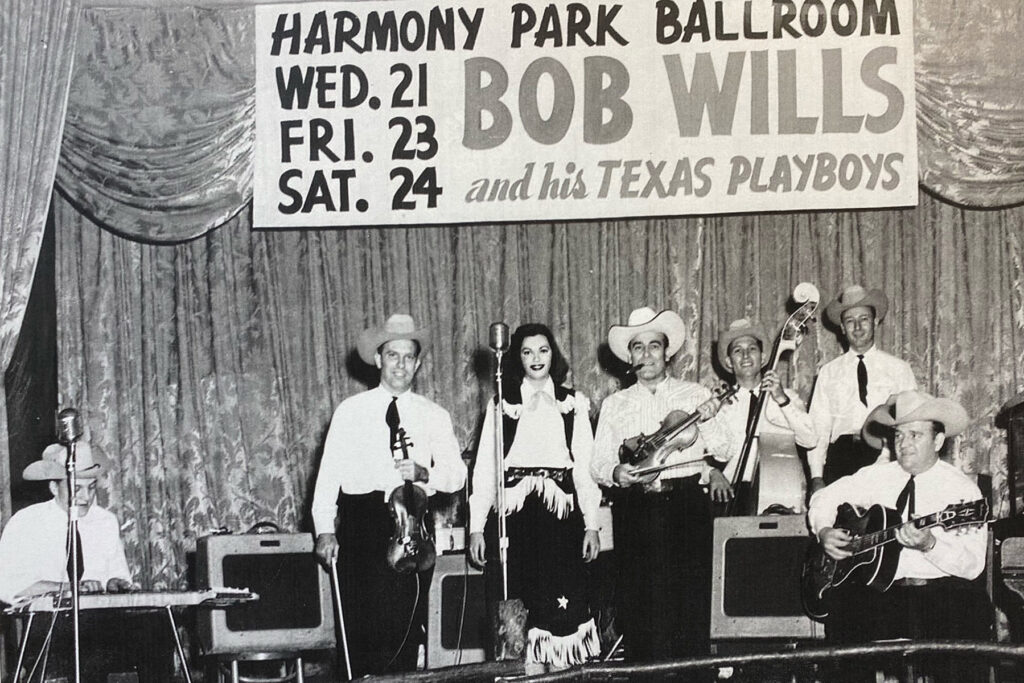

The night in 1952 when the seven Rowe brothers (of the Seven Rowe Brothers band) called up their big-eyed little sister to sing onstage with them in a Dallas club, she cut loose a bluesy “Got You on My Mind.” And in that instant, the young woman’s sheltered life tilted toward the band maestro legend Bob Wills, whose “ahh-ha!” holler and white Stetson signaled the show dog was in the house that night. Right then, the pioneer of Western swing asked the teenager from Duncan, Oklahoma, to join his Texas Playboys band as a vocalist on an 18-city tour.

Things were never the same after that. Not for Bob Wills and certainly not for Louise Rowe.

Western swing is a sub-genre of jazz or country, depending on your expert. Willie Nelson once explained it: “If you cut up what they call Western swing music, you’ll find that there’s some jazz and some blues, and maybe that’s it.” Ray Benson of Asleep at the Wheel splits the difference, calling it “jazz with a fiddle, Count Basie with a cowboy hat.”

Louise knew nothing of these distinctions when she was living in rural Oklahoma with her big family in the 1930s, watching her father instruct her brothers in the Bob Wills way. She was more ignored than excluded from the outdoor classes among the chickens and the dogs and Mama shelling peas. She absorbed the music through osmosis.

In her Hurst, Texas, residence today hangs a painting she made of the homestead with the boys lined up in the front yard, playing instruments, following their father’s bandleader baton. It is captivating folk art. A small girl in a red dress sits in a lower corner of the tableau, hidden in a tree’s shade—Louise’s child self. “While everyone was planning on me learning to cook and sew,” she says, “I was having my little heart stolen by Western swing.”

Some of those lessons stuck with the boys, and after Daddy Rowe passed away, Louise and her mother followed the Seven Rowe Brothers south, as they were lured by the bright lights of North Texas and a town’s tall building topped by a red neon winged horse. That night in 1952, the brothers were playing at Rosa’s Barn on Industrial, where a battle of the bands competition pitted them against Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys.

So upon that stage, after Wills asked Louise to join his band, she answered as she did with every question posed to her: “You’ll have to ask my brothers.”

“He sat down with my brothers,” Louise says today in the living room of her Hurst home. “He promised he’d take care of me like a daughter—and that he did. He was my road papa. I had just turned 19, going on 12. I was protected by my brothers, a country girl who didn’t grow up until I got away from home.”

Around the Big D Jamboree at the Dallas Sportatorium, Louise was the Rowe brothers’ sidekick. “I don’t think anyone knew I had a name until I left here and went to work with Bob Wills,” she says. “When I came back home, I was Louise Rowe of the Texas Playboys.”

That 18-city tour and subsequent bass playing for Wills’ band punched Louise’s ticket to music history. She went on to sing and play bass with two Grand Ole Opry tours, and she traveled with other country music stars. She was the only female instrumentalist Wills ever hired.

Decades later, around 2008, as she was pushing 80, Louise quit singing after a tremor affected her vocal cords. But she still could (and does) beat time on her bass. Recognized in eight Western swing halls of fame and as a Living Legend in Cleburne’s Cowtown Society of Western Music, she’s an icon. There’s no quit in her, although she grudgingly admits that she has gotten a little slow.

Al Dressen hired Louise to play bass and her second husband, Buddy Beasley, her former bandmate in the Southernaires, to play fiddle for several years beginning in the late 1980s. A perfect storm of circumstances had depleted Dressen’s band, and, with a big show looming, he turned to Louise. “I’ll call some of the Texas Playboys. I don’t think they’re doing anything,” she said. Dressen’s voice cracks with emotion recalling when Louise, Buddy, and the Playboys brought the Wills style to his Super Swing Revue. “It was a great part of all of our lives. It’s that special feeling to have members of the band who know how to do it and have the ability to do it.”

Dressen founded the Texas Western Swing Hall of Fame, and he invites Louise to play the annual celebration weekend. “As a bass player, she always stepped up,” he says. “She has great musical abilities. She’s an older person now and gets worn out, but she wants to play and figures some way to do it.”

Indeed, she does. Until the pandemic, drummer Mark Minton played in Louise’s own Texan Playboys for five years on Friday evenings at the Texan Kitchen in Euless. Minton, who’s more Woodstock generation, in contrast to the 89-year-old Louise, stands in awe. “Everyone Louise played with was famous,” he says. “She and her daughter Marci made shirts and had us wearing cowboy hats. I’d never worn a hat in my life.”

Minton is helping Louise with the printing of a cookbook of her road tales and recipes, titled Louise Rowe’s Beans and Cornbread, Musicians Cook and Tell Book of Road Stories, Recipes, and Jokes. He assesses her as “quiet, sweet, almost insecure at times—but she’s a band leader.”

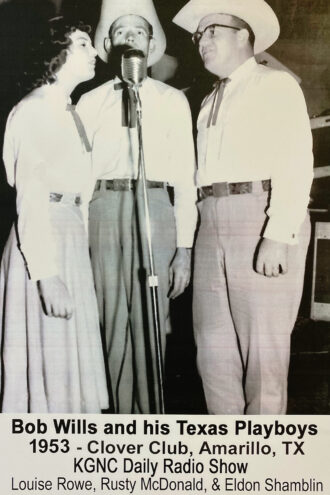

Louise does present a curious mix of self-deprecation and self-promotion. Her vocalizing with the Texas Playboys was really about being able to sing harmony, something she thinks she was born to do. She sang on the live radio shows in Amarillo but never did studio work. She says, “I didn’t have the pizzazz of a solo vocalist. I didn’t ‘feel’ like Ramona Reed,” a well-known singer who could yodel and toured with the Playboys before Louise came along.

She dismisses the vivid drawings of her brothers hanging in her home above her red electric bass as “not professional.” She also says she never thought she was “purdy,” but anyone with two eyeballs would convict her for perjury in the court of common sense. Albert Talley: “She was a water moccasin,” musician-ese for a knockout in looks or talent. They met when he was a 17-year-old pedal-steel guitar player at the Longhorn Ballroom (originally Bob Wills’ Ranch House). At a Longhorn after-party, drunk and despondent, she walked into heavy traffic, and he rescued her. She was divorcing guitar-slinging Western swing artist Tommy Allsup, later famed for the fateful airplane trip on which he gave his seat to Ritchie Valens—but that’s getting ahead of the story.

Bob Wills discovered that his new vocalist could also play an instrument on the next to last night of that 18-city tour, when rhythm guitarist Eldon Shamblin missed the only performance of his career, in Muskogee, Oklahoma. “I walked over and picked up the guitar and started beating rhythm,” Louise says. “Bob Wills looked at me and said, ‘Child, I didn’t know you could do that.’ ”

Wills was impressed again when Louise relieved bass man Jack Loyd so he could step to the mic for a vocal solo. “Child, you can do that, too?” he asked.

Louise hit the trifecta when she heard Wills mumble, “I got a request for ‘Faded Love’ and don’t have anyone to sing third-part harmony.” That was Shamblin’s job. “I walked over to Bob and said, ‘I can sing it,’ and he looked at me with those black eyes. ‘Are you sure, child?’ ” The exacting Wills had to know he would not be disappointed. “When my voice started singing that third-part harmony, high up, I’d never seen him so happy,” she says. “It knocked Bob for a loop.”

The last night of the tour, they returned to Dallas to play a dance at downtown’s Baker Hotel. Louise says, “He called me up to sing and announced the Playboys were going back to California for some TV shows and a tour of the West, and ‘Louise is going with us.’ That’s how I knew I had a job.”

“He sat down with my brothers. He promised he’d take care of me like a daughter—and that he did.”

From then on, Louise played like there was no tomorrow with her new road family of famous musicians. Jack Loyd had quit the band for marriage, and Wills asked her to play bass. Since vocalists don’t have musicians’ callouses, she soon wore blisters that popped. “When I first started playing, I wrapped my fingers with tape and they called me chicken,” she says. “I took the tape off and let the blood fly.” Still, she leaned into her runs on exuberant 4/4 beats. “Get it, girl!” Shamblin shouted. She had won admiration from the celebrated Playboys. This water moccasin could flat play.

Louise toured with Wills until August 15, 1953. “We did a TV show with Chill Wills in Amarillo,” she says. “We were there five nights a week at the Clover Club. We toured Colorado on the weekends. From there to the Cheyenne rodeo in Wyoming and up and down the California coast. Toured Arizona and New Mexico and did three tours back to Texas.

“In Hollywood, Bob took me to Nudie’s and fixed me a uniform like the boys, except where they had pants, I had a skirt,” she says. He also bought her a musician’s union card and an AFTRA union card for TV and radio work.

Wills sometimes had his hands full with his young protégé, whom he had promised to protect like a daughter. On the road, she only had two or three dates, and they had to meet Wills, who would tell them what he expected. Wills told Louise what he expected, too. One morning in Houston’s elegant Rice Hotel, she wore a dress, popular at the time, with the back and shoulders open. When Wills came down for breakfast, he walked over to her table and said, “Go upstairs and put some clothes on, and don’t ever wear that again.”

Like Louise and the Playboys, Chris O’Connell enjoyed only-woman status with the original Asleep at the Wheel. She was fascinated with the Bob Wills stories she heard when she and Louise played together in Al Dressen’s band. “Louise being the only woman on the bandstand with Bob Wills was an extraordinary thing in itself,” O’Connell says. “She held up the bottom end [rhythm] of a big band, and that’s some serious duty.

“Louise considered herself to be one of the guys. She wanted to be regarded as a musician, not as the girl singer or the girl player—just as an equal musician. She was a rock-steady player and a great presence on the bandstand, fun and so easy to work with.

“Louise was under that kind of unspoken contract with Bob that you’re going to show up, you’re going to be professional, look like you fit on the bandstand, you smile and make them dance. That was the big thing. If they weren’t dancing, something wasn’t right,” O’Connell says.

Seldom was it not right at the venues the Texas Playboys packed with hundreds of dancers. “The reason for the big crowds was the fun and excitement,” says Bobby Koefer, the pedal-steel player the year before Louise joined. “When you saw the Texas Playboys, you saw excitement. They created happiness, not sad stuff, and they played without an intermission.”

Louise’s tour with the Texas Playboys ended as Eldon Shamblin drove her to the Amarillo airport. She cried all day because she was leaving her road buddies. Wills had booked the Playboys a year before, when Louise wasn’t with them, and the contract wouldn’t pay for a girl vocalist. Wills did arrange for her to play bass and sing vocals with the house band at the gigantic Reo Palm Isle club in Longview. He told her that she and the Playboys would reconnect after his tour.

That was the plan.

She hadn’t been at the Reo Palm Isle long before friend Tommy Camfield (who co-wrote the Western swing classic “Miles and Miles of Texas”) summoned her to Lawton, Oklahoma, to hear the Southernaires at the Southern Club. “I sat in, played bass, and sang a song,” Louise says. But Tommy Allsup led the band, and she was smitten. Six months later, they were engaged.

Louise lived with her cousin Oletha in Lawton, and Allsup called her to come to Las Vegas, where they married April 30, 1955. They honeymooned at the newly opened Riviera Hotel.

The couple returned to Lawton to reunite the Southernaires, and they played for six months. It was a big life with Allsup. On their first wedding anniversary, he hired a chef and waiter to cook and serve and asked Caesar Massey, the “Gypsy Fiddler,” to serenade. “Tommy presented me with a five-string bass fiddle. It was the best party I’ve ever been to,” she says.

They relocated to Hobbs, New Mexico, and put the Southernaires back together again, this time with two Texas Playboys, brothers Louis and Mancel Tierney, and began to perform at Club Maurice. Soon they learned that producer Norman Petty needed a studio musician in Clovis. Allsup’s expert guitar skills secured that gig, and he worked the sessions for several Buddy Holly recordings, including “It’s So Easy!” and “Lonesome Tears.” Allsup was invited on three tours with Buddy Holly and the Crickets.

On the last tour—by then, Louise, Allsup, and the Southernaires were working out of Odessa—the Crickets’ chartered plane crashed near Clear Lake, Iowa. Louise was watching TV when the national news interrupted that singer Buddy Holly had died. “Tommy was supposed to be on that flight,” she says. “I jumped straight up, but right after, Tommy called and told me he was not on the airplane.”

Allsup told Louise that he’d relinquished his seat because Valens had talked him into it. Valens, Holly, J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson, and the pilot, Roger Peterson, all perished. “That’s who Tommy was. You could talk him into anything,” Louise says. “That’s why he had so many wives.” She adds that Allsup never said anything to her about a coin flip with Valens over who’d get a seat on the plane but notes that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen.

In any case, her marriage had begun to unravel, Louise says, when “a gal started coming to the Silver Saddle Club in Odessa where the Southernaires played.” As events unfolded, Louise went to the hospital with a kidney infection. Louise says, “The woman came to the hospital and paid my hospital bill, and she said Tommy sent her. ‘And by the way, he wants a divorce.’ ”

The divorce news crushed Louise and pitched her into a three-month tailspin, but she could still work. “Drunk didn’t bother my bass playing,” she says. She left Allsup and fled to Dallas, where she played bass and sang with the Aragon Allstars at the Aragon Ballroom. She hit bottom that night at the Longhorn after-party, when Albert Talley snatched her from the path of oncoming cars. Years later, at a Texas Western Swing Hall of Fame recognition, she told Talley, “I need to thank you again for saving my life.”

[img-credit align=”alignright” id=” 866868″ width=”330″]

[/img-credit]

[/img-credit]Around 1984, Louise wrote a snappy song, “The Texas Playboys That Wore a Dress,” after reuniting at the 50th Bob Wills Texas Playboys Reunion in Tulsa with other women who had sung and toured with Wills at different times. The four women had gathered in a motel room at another reunion celebration a short time later, when Louise taught them the song. “They loved it,” she says. “They wanted to sing it the next day. When we performed it, I heard somebody say we ought to make a record.”

Everything fell into place to cut the record in Sacramento with Buddy Beasley and some of the Texas Playboys. Texas Playgirls With Some of the Boys features Louise’s daughter Marci “Gena” Mercadante on fiddle and vocalists Dean and Evelyn McKinney, Darla Daret, and Ramona Reed.

Jason Roberts now heads the historic band called Bob Wills’ Texas Playboys Under the Direction of Jason Roberts. He learned of Louise and her fiddle-playing second husband, Buddy Beasley, via a book-and-cassette tutorial Louise patented in the early 1980s that color codes finger placement. “They called it the Buddy System, and I learned it,” Roberts says. “I got to know Louise in 1986–87 in Austin, with Al Dressen’s band. Louise is special because she’s a singer and a musician, and she thumped the fool out of that bass.”

Marketing the Buddy System stirred Louise and Buddy’s traveling blood, so they hit the road in an RV, going coast to coast and into the South, selling it to music stores. Along the way, she directed and played bass on four CDs, one with ex-husband Allsup, Sentimental Journey. Until the COVID-19 shutdown, she regularly played the Texan Kitchen, in Euless, with her band The Texan Playboys and still crackles with creative energy. Her latest project is the storified recipe book.

Louise and Buddy retired from the road in the early 1960s to raise daughters Rhonda and Marci and devote quality time to their religious activities, but they weren’t ready to completely quit. When one of her brothers developed Alzheimer’s, Louise would stand in for him on nearby shows, and Buddy played fiddle, too.

“Buddy and I had started to straighten out our lives,” she says. Traveling took time and effort, they believed, from their calling as Jehovah’s Witnesses. “We just couldn’t be on the road because we wouldn’t be able to meet with our congregation.” Buddy died in 2016.

Louise now imagines the eternal joy her music will bring. She says, “I assume that we will play the kind that we love because Isaiah 65 says we’re going to ‘long enjoy the work of our hands to the full.’

“Well, that’s Western swing to me.”

Write to [email protected]. This story originally ran in the October issue of D Magazine.