It was more than four hours into the June 5, 2020, special meeting of the Dallas City Council called to discuss the George Floyd demonstrations, and Mayor Eric Johnson had no more patience for bullshit. Johnson had sat quietly listening to one resident after another lecture him about Dallas’ endemic racism and struggles with over-policing. When it was finally his turn to speak, he wanted answers about what had happened on the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge the previous Sunday. Dallas police officers had fired so-called nonlethal rounds of ammunition and tear gas canisters at a peaceful crowd that included many children. Who was ultimately responsible? As the mayor began his cross-examination of Police Chief U. Reneé Hall, her boss, City Manager T.C. Broadnax, interrupted and objected to Johnson’s questions. That set Johnson off.

The meeting devolved into a shouting match. Johnson reprimanded Broadnax for interrupting him. Councilwoman Carolyn King Arnold piled on, equating Johnson’s questioning of the police chief to a public “lynching.” Councilman Adam Bazaldua demanded that Broadnax have the floor. The mayor ordered everyone’s mics muted.

“You don’t have the authority anywhere to censor my questions,” Johnson yelled at the city manager through his mask and into his computer. “You may run this city, but I run this meeting!”

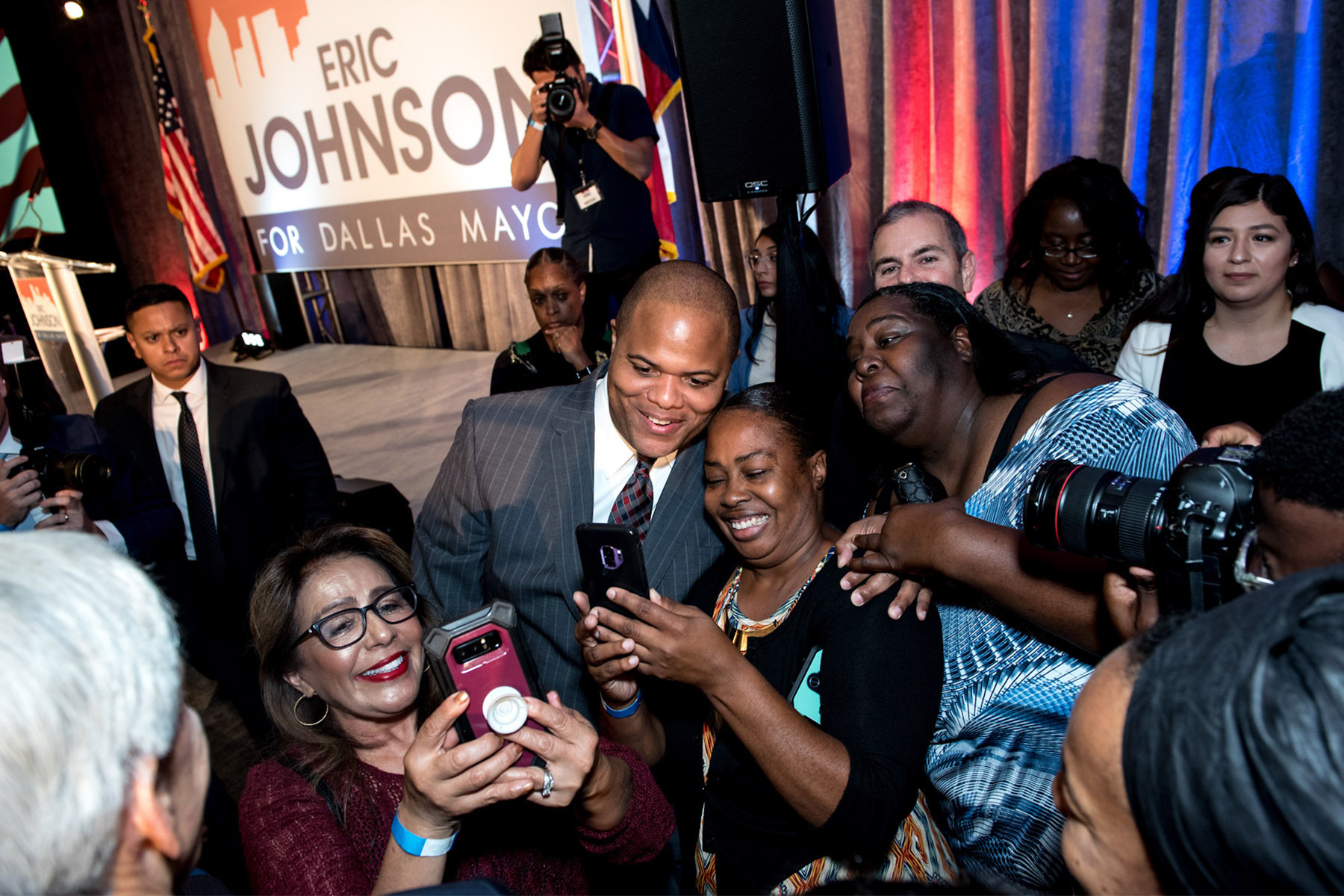

It was an ugly end to an emotional week, and it revealed a problem that had been smoldering at City Hall for months. When Johnson became mayor, in 2019, he was presented to voters as a reincarnation of Ron Kirk—a magnanimous, back-slapping unifier who would restore cooperation and decorum to a Dallas City Council that had become defined by discord. But now, two years into his first term, the city’s government has never been more divided. His supporters loved the Eric Johnson who, as a state legislator, had earned a reputation as a progressive dynamo. They now say they don’t recognize the Eric Johnson who is mayor—a petty, thin-skinned man who turns his back on friends, butts heads with the city manager, picks fights with Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins, flirts with Gov. Greg Abbott on social media, and poses for chummy pictures with Sen. Ted Cruz.

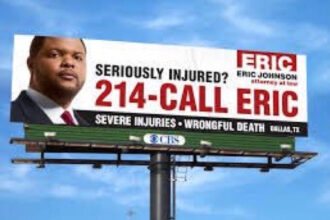

Trying to understand Johnson’s political and interpersonal calculations is difficult. He doesn’t give in-depth interviews; he denied D Magazine’s request to speak for this article. Instead, he has opted for a media strategy that focuses on television appearances, scripted press conferences, weekly email newsletters, and press releases. Even Johnson’s colleagues on the Council say they have trouble getting the mayor on the phone. In fact, save for a few two-dimensional profiles of Johnson that ran during the campaign, nothing written has ever thoroughly explored his rather remarkable life.

Voters were simply introduced to Johnson as the “West Dallas whiz kid,” as a Dallas Morning News story dubbed him, who escaped poverty to attend a string of Ivy League schools before returning to devote himself to public service. That story is not untrue; it also isn’t close to complete.

Now, as Johnson works behind the scenes to unseat three of his rivals on the Council in this month’s municipal election, the question of who Eric Johnson really is has never been so tightly bound to the fate of the city.

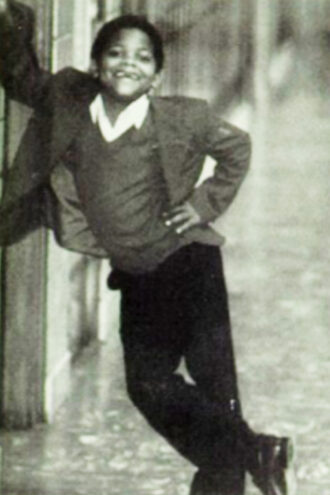

When young Eric walked into the first-grade classroom at C.F. Carr Elementary in West Dallas, his teacher, Lea Ann Aderhold, recognized that he was different. He had those cherub cheeks, twinkling brown eyes, and puckish smile that would one day charm political backers. “He was hungry to learn,” Aderhold told me on the phone from her home in Florida. Toward the end of the year, Aderhold began to worry that her star pupil needed more than what he would receive in West Dallas’ public schools. She made a call to the Greenhill School that led to a scholarship that changed the direction of Johnson’s life.

Johnson grew up in a West Dallas neighborhood hit hard by crime and poverty. A 1984 D Magazine article titled “The Forgotten City” describes a landscape defined by the towering smokestack of a lead smelter that poisoned generations of impoverished children and prisonlike housing projects that were the largest in the city. But the depictions then of West Dallas left out the rich community life that framed the world of Johnson’s childhood. His neighborhood was rooted in the Dallas West Church of Christ. Ocie Kazee-Champion, whose parents helped found the church, remembers Johnson as an outgoing toddler running around the sanctuary. On Sunday evenings after service, folks gathered at the Kazee home for cake and coffee. Johnson was a regular presence in the home. He was close friends with Kazee-Champion’s nephew Eric, whom they called E. The boys cut each other’s hair and played music. Johnson also hung with Kazee-Champion’s father, who would tell Johnson stories about picking cotton or working the railroad in his youth. Johnson would sit and listen for hours. Once, Kazee-Champion came home and found that all the children had gone out to play, but Johnson had stayed behind.

“Why aren’t you down there with E?” Kazee-Champion asked.

“I’m talking to Papa Z,” the boy replied. “He’s telling me all the stories.”

After Johnson received the scholarship to Greenhill, he climbed into a van each morning provided by the Boys & Girls Clubs of Greater Dallas to commute the 15 miles north. It is impossible for anyone but those euphemistically called “scholarship kids” to understand what it felt like to stare out the window and watch a stream of neighborhoods transition from squalor to opulence.

Johnson may have been one of those outsiders, but he arrived at Greenhill full of confidence. Courtney Shepherd, a scholarship kid from Oak Cliff, remembers sitting in the back of his second-grade class when Johnson was introduced for the first time. Shepherd says by the afternoon of his first day, Johnson was in the thick of it with his classmates on the soccer field.

Elaine Velvin, Johnson’s second-grade teacher, says his vibrant personality made him stand out. “I loved it,” Velvin says. “As a teacher, I always said I would rather have a child whose energy I had to direct, rather than instill.”

Johnson established himself as one of the smartest and most popular kids in his class. In the fifth grade, he founded a student newspaper and ran a classmate’s student council campaign. By high school, Johnson’s broad shoulders made him a standout fullback for the Hornets. What classmates best remember about him is his wit and penchant for getting tangled in lengthy debates about any topic. He once spent weeks arguing with his classmates about the correct pronunciation of “Raskolnikov,” the protagonist of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. He watched Jeopardy! on the game-tape television in the locker room. The White kids on the football team referred to Johnson and Shepherd as The Blackfield, and the two runners plowed over the prep school kids in their football conference.

Johnson established himself as one of the smartest and most popular kids in his Greenhill class. In the fifth grade, he founded a student newspaper.

Greenhill offered him other glimpses into the world beyond West Dallas. Johnson’s little sister also earned a scholarship to Greenhill, and she became close friends with the daughter of Tom Dunning, the former chair of the Dallas Citizens Council who ran for mayor in 2002. Johnson often rode with his mother to Dunning’s palatial Preston Hollow home to pick up his sister. He struck up a friendship with Dunning, and, when Johnson was a senior, he caught Dunning by surprise when he asked him if he could be his “Black godson.”

“No,” Dunning told him. “But you can be my godson.”

That year Johnson was accepted into Harvard, elected homecoming king, and was chosen to address the class during their 1994 graduation ceremony. In his speech, he cracked jokes about some of the disparities he had experienced at the school. On his senior page in the 1994 Greenhill yearbook, Johnson thanked his mother and teased Shepherd, his buddy in the backfield, for joining the Army and heading to West Point. To Robert Agnich, Greenhill’s quarterback, Johnson made a promise: “See ya in the White House!”

He also addressed an entire cohort of Greenhill kids. Here’s how his page ends: “All of U guys on the Boys’ Club van: Listen 2 me now, I’m serious. Don’t pay attention 2 those people who look down on U because you’re from the hood or because U ride the bus. U don’t have 2 live in a big, fancy house in North Dallas or drive a Porsche 2 make it through GHS although it may seem like it, sometimes. Remember who U are and where U come from, and people will have no choice but 2 respect U. Peace out G’s.”

By the time he ran for the state Legislature, Eric Johnson had put together an impressive résumé. At Harvard, he pledged Kappa Alpha Psi, a historic Black fraternity; won multiple public service scholarships; and directed a summer program for children living in the Cambridge projects. In 1998, Johnson returned to Dallas for a period and served as an aide for state Rep. Yvonne Davis and worked at an investment bank. He left again for New York, where he worked as a graduate intern at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. This time period is detailed on his Wikipedia page but does not appear on his résumé. In any case, he then attended law school at the University of Pennsylvania and earned a master’s of public affairs from Princeton’s School of Public and International Affairs.

Then Johnson came home and married his wife, Nikki. Velvin, his second-grade teacher, had introduced the two at a Greenhill alumni event. Their wedding reception was at Dunning’s house. The young couple rented an apartment at South Side on Lamar, and Johnson worked as an associate at Haynes and Boone before striking out as a personal injury attorney and eventually moving into municipal finance law. South Side was the perfect place to live for a young, well-educated Black lawyer with an eye on political office. In a 2010 D Magazine article, political consultant Shawn Williams described South Side as the epicenter of an emerging Black renaissance in the city, where residents might expect to bump into Dallas County Commissioner John Wiley Price, NAACP President Juanita Wallace, or playwright Liz Mikel. Jan Gore, a former Ann Richards staffer, ran a Caribbean restaurant at South Side, though Johnson knew her from the days when Gore’s mother cut his hair at her Oak Cliff barbershop.

“[Johnson] was part of this big family,” says Marion Marshall, an artist and former fashion designer who runs a wedding and event planning business out of South Side. “He was a happy, very engaged person here at South Side.”

In 2009, Khraish Khraish was helping his father run a real estate company that owned about 500 properties in West Dallas, which largely meant pushing out squatters, cleaning up drug dens, investing in renovations, and paying off old liens and fines. He noticed campaign signs popping up around the neighborhood and wondered if the Eric Johnson running for the Texas State Legislature’s 100th District was the same Eric Johnson he was friends with at Greenhill. He rang the campaign office, and the old friends arranged to meet. When he learned that Johnson had returned to West Dallas to serve the community where he’d grown up, Khraish wrote him a check for $10,000. Khraish also helped tap into their Greenhill network to raise funds. Tom Dunning and his daughter contributed, as did businessman Albert Black and radio personality Tom Joyner; their sons Tre and Oscar were friends with Johnson. Kazee-Champion worked on the campaign, and Gore catered campaign events.

On paper, Johnson was a terrific candidate, but in the Democratic primary, he was up against Terri Hodge, a 13-year incumbent who had the backing of the Dallas County Democratic Party. Even though Hodge was ensnared in an affordable housing corruption scandal, no sitting elected official would break ranks to endorse Johnson. But Johnson embraced his outsider status.

“He always wanted to pay respect to those who had come before him,” says Oscar Joyner, who also graduated from Greenhill. “However, he’s always wanted to make sure that he paves his own way. He’s never been one to seek anybody’s endorsement.”

After Hodge pleaded guilty for tax fraud related to the housing scandal, Johnson won easily. But in the Texas Legislature, he was still considered something of an outsider. According to one house member speaking on background, the Black Legislative Caucus initially regarded Johnson as a “pariah” because he had challenged Hodge in the primary.

“The reputation that I got about Eric at the time was he was a bit of a lone ranger,” says former Republican Rep. Jason Villalba, who was a freshman during Johnson’s second legislative session in 2013. “He did not engage in the kind of extracurricular after-hours type of relationship building that many of the members of the Dallas delegation had.”

It wasn’t only down in Austin that Johnson was hard to get time with. Working in his West Dallas district office, Kazee-Champion received calls from constituents who complained they had not seen Johnson around the neighborhood. So Kazee-Champion blocked out time on his calendar to knock on doors. But when Johnson saw his schedule, he lost his temper. “Don’t put anything on my calendar until I give you permission to do it,” Kazee-Champion remembers Johnson shouting at her.

Kazee-Champion had seen this side of Johnson before, and she had learned to deal with his outbursts with a mother’s patience. Johnson was still huffing and puffing as they drove through West Dallas, but by the end of the day he cooled off and was grateful. Catching up with neighbors, he told her, helped remind him what he was fighting for in Austin.

“Sometimes when you’re full,” Kazee-Champion says, “you forget what it is like to be hungry.”

Depending on the source, you hear different accounts of his time in Austin. Some say he has a brilliant mind for writing legislation. Others say Johnson attached his name to a lot of bills he had little to do with. But his decadelong tenure in the Lege is best encapsulated by his attempt in 2015 to pass a sweeping expansion of pre-K education.

The issue could not have been closer to his heart. Even though he didn’t attend pre-K or kindergarten, Johnson knew what early education meant to children. By the time Johnson was 3, his mother, Alice, had taught him how to read. She created Montessori-like puzzles for her bright son, filling brown paper bags with flour and letting him feel their weight. Then she scooped out some flour and asked her son to hold the bags again and guess how many cups she’d removed. Everyone always spoke about how gifted Johnson was, but he knew that wasn’t the whole story. Despite their poverty, his mother had figured out a way to get him started. Now Johnson was in a position to give every kid in Texas that same advantage.

Johnson co-authored a bill. He drummed up media coverage and rallied legislators to the cause. But as momentum built behind his bill, the Republican leadership under Gov. Abbott recognized an opportunity to score a win. They introduced their own pre-K bill, which provided much less funding than Johnson’s proposal. As the majority party’s bill picked up steam, school district lobbyists began to support it, recognizing that it was imperfect but likely to pass. Johnson’s bill was abandoned, and he was incensed. When the Republicans’ pre-K bill came to the floor, Johnson voted against it.

It is not easy to pass meaningful legislation in Austin as a member of the minority party, but then the Texas House always seemed like a stepping stone for Johnson. It was widely believed that he had his eye on Eddie Bernice Johnson’s Congressional seat once she retired. With Khraish, he mapped out a path to statewide office—maybe attorney general, lieutenant governor, and even perhaps governor—that led through a Dallas County judge seat. Johnson positioned himself by raising more than $400,000 by the end of 2018. That year, he also launched a Hail Mary pass to become the House speaker that most of his colleagues brushed off as an attempt to boost his name recognition or secure a plum committee assignment.

Johnson’s growing ambition rubbed some colleagues the wrong way. Villalba, a Republican, worked with Johnson to advance a bill to expand LGBTQ rights, but Johnson wasn’t happy when the media attention focused on Villalba. “I think he was pretty upset,” Villalba says. “He jokingly would rib me, ‘Look, I put all this time into writing a bill that is going to change Texas, and the Dallas Morning News puts you at the top of the byline.’ ”

Other legislators tell stories about Johnson doing more than ribbing. He was known for blasting fellow house members with enraged late-night text messages. His texts became so infamous that they had a nickname—“being Eric-ed.” Some donors complained that he would lean too heavily on them.

Johnson’s tantrums, however, did help him get noticed. Former D Magazine columnist Eric Celeste got to know Johnson through the Book Club, a series of cocktail gatherings Johnson hosted with then Dallas Councilman Philip Kingston to network Dallas political and media types. Celeste says he would receive late-night texts from Johnson complaining that he hadn’t been quoted in his latest piece or that Dallas Observer columnist Jim Schutze wasn’t calling. The result was generally favorable coverage.

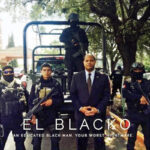

a shot at the Dallas County Democratic Party in a social media post in which he called himself “El Blacko.”

Johnson’s most public outburst was sparked by the Dallas County Democratic Party’s decision to hire Johnson’s former opponent, Terri Hodge. Johnson posted a photo on Facebook of himself in front of a posse of young men in military fatigues holding assault rifles with the caption “El Blacko: An educated Black man is your worst nightmare.” And he threatened the leaders of his local party. “What my political enemies fail to understand is that I was built for war,” Johnson wrote. “Don’t let the three Ivy League degrees fool you.”

No one thought that Johnson’s next political battle would be the fight for Dallas mayor. But in December 2018, Johnson called Khraish and told him he was considering entering the crowded race. Khraish didn’t understand why Johnson wanted to be Dallas mayor, but as they analyzed the race, it looked like he could win it. As far as Khraish could tell, that seemed to be Johnson’s motivation: to get in the fray with the lengthy list of civic leaders vying for the job and take them down. It would be just like high school.

“I made it a point to beat every single student at Greenhill,” Johnson told Khraish. “Whether academically, athletically, or socially, I would beat them all. This poor Black kid from West Dallas was going to beat every White kid who had every advantage. They were going to lose to me.”

The kids who rode the Boys & Girls Clubs van talk about the pressure they felt having been handed an opportunity to escape poverty. “Our parents had come of age during the civil rights movement,” Shepherd told me. “So there was this belief that, as a Black student, you can’t just be as good. You’ve got to be better.”

That seemed to be Johnson’s motivation in the mayoral race: to get in the fray with the lengthy list of civic leaders and take them down. It would be just like high school.

Johnson looked around at Greenhill and saw kids who had no idea that, for him, doing well at school wasn’t merely about getting into a good college. It was a fight for survival. He had seen the stakes of this struggle firsthand. Johnson’s little sister left Greenhill after the eighth grade to attend her local public high school, and her life took a sharp turn outlined in a trail of legal documents. Beginning in 2008, an addiction to crack cocaine led to multiple arrests for prostitution. The night Johnson won his first election, his parents visited his sister in jail before driving across town to attend the victory party.

Darryl, one of Johnson’s older brothers, wrote an essay in 2013 for the website Little Black Village. His words add more detail to what Johnson’s fight for survival looked like. “I was a middle child and witnessed everything growing up from love everlasting, mental illness, poverty, child abuse, and domestic violence,” Darryl wrote. “My parents did the best they could with what they had—but it was a fact that my ‘being born’ did not sit well with my father. He made that known on several occasions—even telling me that ‘If I could take back that seed—I would!’ Words that I will never forget.”

No one emerges from childhood poverty unscathed, but as much as Johnson wanted to escape, he didn’t want to turn his back on West Dallas. He had seen that, too, at Greenhill. Most of the scholarship kids arrived in rich, White North Dallas and did their best to assimilate. They stopped associating with their friends in their neighborhoods. They changed the way they spoke. They wore different clothes. They traded in their culture to be accepted.

“I didn’t do that,” Johnson told Khraish. “I never wanted to do that.”

The 2019 mayoral election was so packed with storylines—from the crowded field of civic leaders to the Ray Hunt-led coalition that consolidated business establishment support around Johnson—that it was easy to overlook what an utter pummeling Johnson delivered to his opponents. He entered late, attended few debates, continued to serve in the state Legislature, faced off against eight candidates who could have each won in a different year, and plowed over the competition just like he had run over the opposition as a Greenhill Hornet. Even before he won, he started beating up on anyone who wouldn’t line up behind him.

After asking Khraish to serve as co-chair of his campaign, Johnson rescinded the offer. The two haven’t spoken since. Johnson also dropped his longtime treasurer, the Rev. Dr. Frederick Haynes of Friendship West Baptist Church, who hasn’t spoken to Johnson since he won the election. Many of the candidates in the crowded field counted themselves as Johnson’s friends and supporters. Lynn McBee, who started donating to his campaigns in 2009 and completed the Leadership Dallas program with Johnson, said she was shocked when he entered the race. During the campaign, Albert Black told D Magazine’s EarBurner podcast that Johnson had once considered him a second father and that his entry into the race felt like a “civil war.”

After Johnson moved into City Hall, even some of his supporters felt locked out. Maybe he was just too busy. Not long after being sworn in as mayor, Johnson joined Locke Lord, a campaign contributor, as a partner in the firm’s bond practice, which surely took up a lot of his time. Whatever the reason, developer Jack Matthews’ experience is typical. Matthews developed South Side on Lamar and has supported Johnson’s political campaigns since 2013. By the time Johnson entered the mayoral race, Matthews had already committed to endorsing McBee, though Matthews did endorse Johnson in the runoff against Scott Griggs. Matthews wouldn’t comment on Johnson for this story, but he did confirm that, while he met with previous mayors numerous times during their first two years in office to discuss projects in which he is involved, like the downtown high-speed rail terminal development, he has not met with Johnson once since he took office.

Matthews was one of more than a dozen friends and associates who didn’t want to talk about Johnson for this story. Dallas ISD trustee Dustin Marshall rode that Boys & Girls Clubs van with Johnson and has donated to his campaigns. He also declined an interview request.

Mark Melton, a lawyer who testified in Austin in support of Johnson’s pre-K bill, was eager to work with the new mayor on ethics reform. After Johnson took office, Melton met with him and laid out a plan. He offered to take an ethics reform proposal and run it past council members, soliciting feedback and whipping votes. Johnson wasn’t interested. “He looked at me and said, ‘If you have a draft, you can bring it to me, and I’ll push it through the Council,’ ” Melton says. “ ‘I’m the mayor, not you, Mark. I’m the one who got elected.’ And I just thought that was weird.”

Johnson also didn’t appear interested in the arduous back-scratching of council members that generates the real source of power in Dallas’ weak-mayor, council-manager form of government. A few months into his term, he instructed council members to funnel all their attempts to communicate with him through his chief of staff, Mary Elbanna, and chief of policy and communications, Tristan Hallman. There is an understanding among council members and those doing business with the mayor’s office that Hallman runs the show. Even before COVID-19 forced all city business online, they say, Johnson was rarely seen around City Hall.

Johnson’s behavior even scared off some of the very people who had helped orchestrate his mayoral victory. Sources say the Dallas Citizens Council crowd is frightened by the mayor they helped create. Oilman Ray Hunt, Ambassador Jeanne Phillips, Oncor executive Allen Nye, construction magnate Peter Beck, and Woodbine Management CEO John Scovell all declined or did not return requests to speak to D Magazine for this article.

Those who believed that the Eric Johnson taking office would be the progressive populist who once called himself El Blacko and stared down the Dallas Democratic establishment have also been disappointed. Darryl Blair Sr., whose weekly newspaper, the Elite News, endorsed Johnson, says he has been frustrated by the mayor’s thin skin, the infighting at City Hall, and his response to policing in Black communities. “He’s a good guy on a personal level, but his politics are piss poor,” Blair says.

After those protests, Johnson emerged as one of the loudest voices in Dallas against reallocating part of the city’s police budget to create new ways to invest in communities impacted by over-policing. Protesters began driving by the mayor’s house on a nightly basis, honking their car horns. Rev. Haynes called Johnson’s response to the demonstrations a “missed opportunity.” Marshall, the artist who lives at South Side, says she wanted to see more from her former neighbor. “There were a lot more expectations around him—a Black man in America and the mayor of a major city,” she says. “He’s just kind of been a wallflower through this whole process.”

But not everyone has a negative view of Johnson’s first two years in office. The farther you back away from City Hall and the people involved in Dallas politics, the more the view of Johnson’s tenure brightens. Through his weekly newsletters, social media presence, and frequent appearances on local and national TV news programs, Johnson has projected an image of confidence. Bobby Abtahi, former president of the Parks and Recreation Board under Mayor Mike Rawlings, says that he realized Johnson had figured out a way to bypass the noise of City Hall politics when he and his family walked into his mother’s house one day and she ignored them because she was busy reading an email from the mayor.

James Armstrong III, senior pastor of the Community Fellowship Church in West Dallas and the president and CEO of Builders of Hope Community Development Corporation, also believes the infighting at City Hall has confused many people’s perceptions of the mayor. Armstrong knows Johnson better than most. When he was in the state Legislature, Johnson mentored Armstrong, who grew up in West Dallas. To this day, Armstrong defends the mayor, which is a bit surprising. After Johnson ran for mayor, Armstrong believed he was a natural fit to succeed him in the Lege. He ran for his seat but didn’t expect his mentor to endorse him. Armstrong says it has always been Johnson’s policy not to endorse political candidates, and he insists there are no hard feelings, even though Armstrong lost the race. He sees the experience as an example of Johnson’s strong political principles that make him ideal to lead the city.

“As misunderstood as Mayor Johnson is, people have to know that he really loves our city,” Armstrong says. “He has a heart to see true change. That may come in the form of being impatient with bureaucracy or political players who are seeking self-gain. But at the end of the day, Mayor Johnson is someone who has grown up on the streets of our city—the streets marked by potholes and crime—and someone who is really an example of what could be for all our kids who grow up in these neighborhoods.”

This election cycle, Johnson has abandoned his past political principle and is endorsing candidates—albeit unofficially. The background chatter about these races is what you’d expect: Johnson is playing ugly, employing Lege tactics in a city election. If you decode Johnson’s photos with Ted Cruz and his cozy working relationship with Greg Abbott, you will find clues that Johnson will come out as a Republican to run for statewide office. But the more I spoke to the people who really know Johnson, the more this image of the Machiavellian mayor crafting a path to power fell apart.

Dunning says Johnson has always been focused on acquiring the two things he never had as a child: a house and a dog. Kazee-Champion says it is true that Johnson is always working on a plan, that he is always two steps ahead of everyone else. She also admits that sometimes Johnson becomes so fixated on his plans that he bowls over the people around him.

The chatter is that if you decode Johnson’s photos with Ted Cruz and his working relationship with Greg Abbott, you will find clues that Johnson will come out as a republican.

Perhaps, rather than a stepping stone to some other political ambition, Johnson’s run for mayor, which confused so many people, was an effort to focus on his family. In 2018, he and his wife built a new house in Forest Hills. They are now expecting a third child. His eldest son was beginning to act up at school when Johnson was away in Austin for weeks and months at a time. Velvin, the second-grade teacher, whom Johnson named to the Landmark Commission, says that when they talk, they don’t talk politics. They talk about what it is like raising two little boys. The warm family images Johnson posts to Facebook, she says, are not part of some political show. “That’s not a photo op,” she says. “That’s life.”

When Johnson and Joyner get together, they also talk about being parents. Their children are beginning to live through the same struggles they experienced as Black kids at Greenhill.

“We’re also looking at two Black boys who are going to be one of only four or five Black people in an entire class,” Joyner says. “Our golf conversations tend to be about how we can get our sons and our children around other Black kids. How are we going to make sure that they get a knowledge of self?”

It is strange to think about these questions knocking around in Johnson’s head as he looks out the window and sees Black Lives Matter protesters in front of his house. That may have been what inspired him to reach out to Phil King, a Republican state legislator, to work on a bill that would extend state privacy protection for elected officials to local office holders. Or maybe it was something else that triggered Johnson to pick up the phone and call King. I don’t know.

The more I learn about Johnson’s story, the more frustrating his refusal to be interviewed becomes. There is so much I want to ask him. I want to ask him what it was like to be taken from his neighborhood in the second grade and thrust into an environment where he felt pressure to turn his back on the community where he grew up. I want to ask him what it feels like to bear on his shoulders the weight of expectations, of always having to succeed, and if that drives him to prove that he is always the smartest guy in the room. I want to ask him if being the West Dallas whiz kid necessarily isolates him in his strange and particular experience of the world—that rising out of poverty in Dallas means escaping childhood trauma only to lose something of yourself and your connection to community, home, family, and friends in the process.

But I understand why Johnson won’t talk. Why would he trust someone like me with an honest description of what it’s like to be Eric Johnson? This lack of trust is something Khraish spoke to me about. As Johnson confided in him that he had resolved to be the best—the smartest, the strongest, the most popular guy, beginning at Greenhill and culminating in his run for mayor—Khraish realized that there was something that Johnson didn’t understand. That whole time, everyone was rooting for him.

“He did it. He beat us all,” Khraish says. “But what he doesn’t know is, we were happy for him.”

This story ran in the May issue of D Magazine with the title “Invisible Man.” Write to [email protected].