Last year, Tim Coursey published his first short story, “Shelda: A Fable Involving a Well,” in Southwest Review, SMU’s long-running literary quarterly. It was an impressive feat for a couple of reasons. One, though he has delighted friends for years with his emails—the writer David Searcy calls them “sometimes incomprehensible little gems”—Coursey started writing in earnest just a few years ago. And, two, he was 72 years old at the time.

The latter was likely the more remarkable aspect to those who know him, though still hardly eyebrow-raising. After all, he’s Tim Coursey.

You see, there are two groups of people in Dallas. There are those who know Coursey and think he’s “a stone-cold genius,” as Ben Fountain, the bestselling author of Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, puts it. To them, he’s a sort of North Dallas da Vinci, an artist and craftsman capable of just about anything. And then there is a much larger group: those who have absolutely no idea who he is.

If you find yourself in the latter camp, even if you consider yourself well versed in the Dallas art scene, both past and present, don’t worry. That’s kind of the point. Coursey has always liked making things, usually sculpture in some form, enjoying the process and the end product. But he has never had much patience for everything that comes after he has made those things, the song and dance of being an artist.

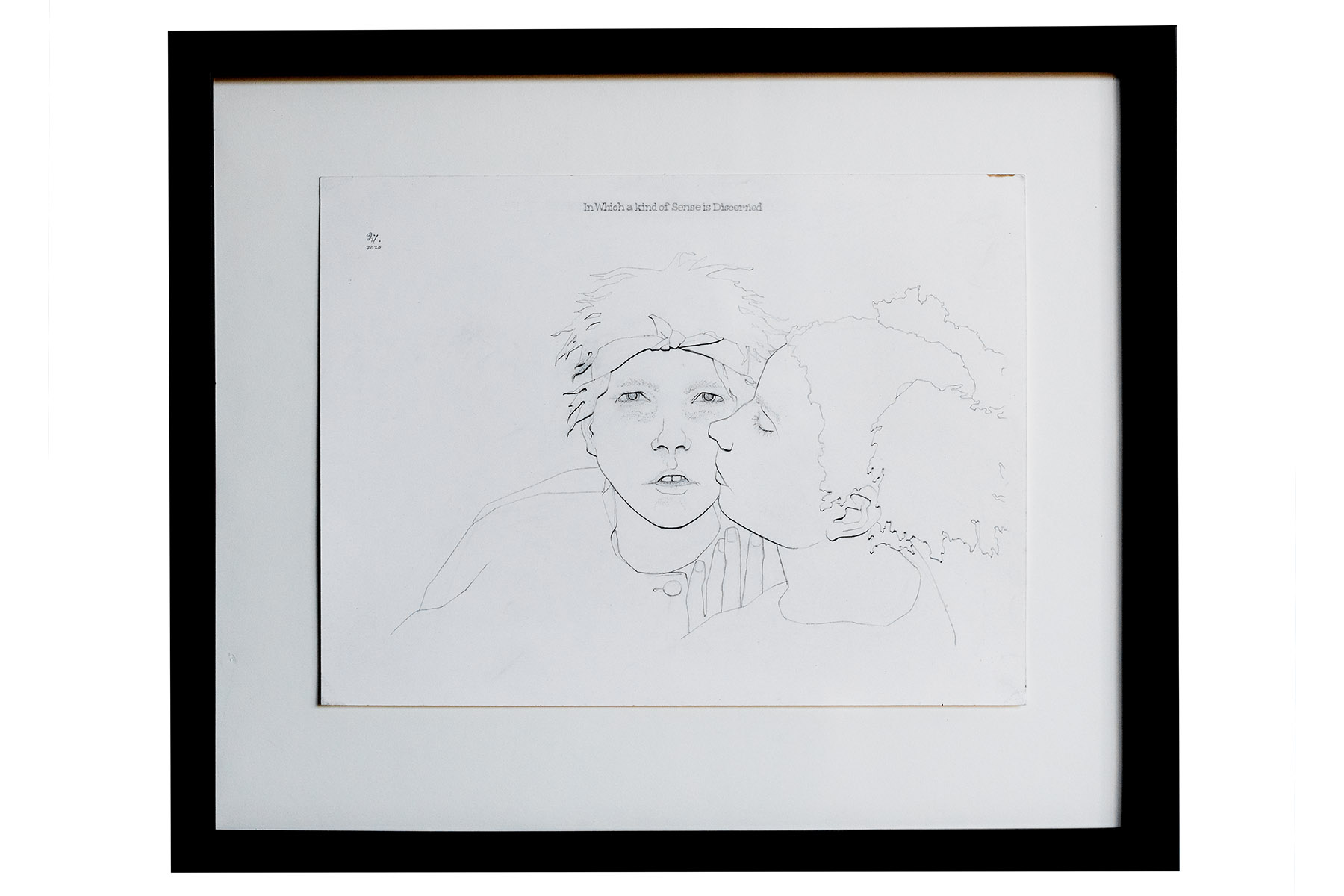

“Driving Lessons: Thirteen Stories,” his new exhibition at SMU’s Pollock Gallery (on view through March 13), speaks to both sides of that divide. It showcases the breadth of his talent and skill across disciplines, incorporating his writing (spiral-bound collections of his stories, including “Shelda,” are stacked around the room, and broadside excerpts printed on mulberry paper are pinned to the walls) as well as carpentry, metalwork, illustration, and design (he reworked and improved upon a double-action Geatish lock common to the sixth century for Hope Chest, the show’s sculptural centerpiece). Another writer friend, Kendra Greene, says the exhibition is “like walking into his mind.”

It’s also the first solo showing of Coursey’s work since 2014 and the first in Dallas since he can’t remember when. Even back in 2014, he had joked that “the artist reemerges from obscurity.”

“Tim is a person who is very low-key, very under the radar of most people, and I think he intends to be that way,” says Kevin Vogel, who counts himself among the group of Coursey’s admirers. Vogel runs Valley House Gallery & Sculpture Garden with his wife, Cheryl, and has been a friend and fan of Coursey’s for decades. “There is a cadre of people who know him and respect him greatly. But if you just went around to the gallery scene in Dallas and asked the dealers who Tim Coursey is, probably three-fourths of them wouldn’t know who he was.”

Vogel says more people are probably aware of Coursey in the design world, because of his long-standing reputation as a furniture builder and designer, the artisan of choice for people who can afford bespoke chairs and chests and cabinets and tables. But even in that realm, his presence is stealthy.

For example, if you have been to the Meadows Museum in the past 20 years, you have likely come across some of Coursey’s work, whether or not you realized it at the time. The high-backed, light-colored wood chairs with the complex curves? Those are his. They are part of a collection of furniture that Vogel commissioned Coursey to build for the museum’s print and drawing room, donated when the institution moved into its current home in 2001.

“That’s the furniture that you see used all the time in the Meadows when they have a display area that they set up,” Vogel says. “He crafted every chair. He crafted the tables. He crafted the book holders and all that kind of stuff.”

In a way, it is perhaps the ideal situation for Coursey. His work eventually found its way into a museum but not as part of an exhibition. It came in quietly, through a side door. That has always been his preferred entrance.

I find Coursey one January morning standing at the wide double doors that open the flank of his workshop to a driveway and a compact flatbed pickup outside. Watching him shuffle around the shop, I’m not surprised that Coursey has managed to stay largely off the art world’s grid all this time. He looks like he could disappear right before your eyes if he wanted to, or at least like someone who has tried. Now in his eighth decade, it’s almost as if he has evolved to slip through the world unnoticed. He’s thin and wiry and curls into himself, a question mark ending in an unruly thatch of silvery hair.

But maybe he has the right idea. It’s the day after the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. Not a bad time to escape. “For the plot being so dumb,” he says of what happened, “it’s a pretty good movie.”

He says this quietly, the same manner in which he says all but one word (“Death!”) while I’m in his presence. He doesn’t speak in a whisper. It’s more like he has turned the volume knob of his voice all the way to the left, the habit of a man who has long struggled to overcome his almost paralyzing shyness. A few weeks ago, Coursey spent half an hour walking me through the Pollock exhibition the day before it opened to the public. When I listened to a recording of our talk, I found that his side of the conversation sounded as though it were coming from another room, through a closed door, despite our being only a few feet apart in an empty gallery.

“All of his work, his art, tends to bring with it a narrative. There’s some sort of story here.”

It is probably for the best, then, that Coursey’s professional pursuits have generally involved him spending time in the studio behind the home he shares with his wife, Melanie, off Hillcrest Avenue. He built the workshop, painted white and blue like the house in front, when he was in his 40s. (He jokes that if he had known he’d still be using it 30 years later, he might have made everything shorter.) It’s a simple structure with a few elegant touches, like the trio of skylights along one side of the roof that halo his head with natural light even on an overcast morning. It’s a place to get things done, and Coursey has put it to good use over these past few decades.

He can make anything here. In the jewelry shop in the front, separated by a door, he does casting and jewel-scale welding, anneals large pieces of copper and smaller pieces of iron, forges small things like knives. “I’m a pretty good steelworker as well,” he says. In the larger room, he has built ecumenical hardware for various churches, furniture of all shapes and sizes. He didn’t know there was such a thing as a cellist’s chair until he was hired to build one.

“I started making furniture for friends,” he says, “and then acquaintances, and then complete strangers, and then people associated with galleries and people associated with decorators.”

If he fell into furniture making as a career, however, a way to send two kids with learning differences through private school, he treated his practice with the same level of thought that he approaches his art. Not that he sees it as art. It serves a function. But Coursey always gives his clients more than they ask for—or even comprehend, really.

“When he makes furniture for clients, there’s always a conceit somewhere in the furniture that you wouldn’t even know was there,” Vogel says. “There’s something that, if you did not understand the history of furniture making, you didn’t know he might be combining two periods of furniture, very subtly in the curve of a chest. Because he injected that in such a way that, for him, it’s intellectually stimulating, but for the observer, you’re just going, Oh, I love that furniture.”

Vogel gives me an example. A number of years ago, he and his wife commissioned Coursey to build a screen for a window that looked out onto a particularly ugly area of their property. Their only requirement was that it needed to be translucent, to let some light into the gallery.

“Well, he knew that I loved paper,” Vogel says. “He knew I was very interested in prints and drawings, and anyone interested in prints and drawings, just by their very nature, you like paper, too.”

Two weeks later, Coursey came by to install the wood screen. After he’d finished, he told Vogel to look really closely at it. Vogel saw that, to create the screen, Coursey had used maybe 100 square holes. He was impressed, but he still didn’t see it.

And then, finally, it hit him. What Coursey had created for him.

“I turned around and looked at the screen and went, Oh, my God, he made a piece of laid paper,” Vogel says, referring to the old handmade style of paper, still a favorite of artists. “It had the chain lines and the laid lines formed by the grid pattern that he had created, knowing my love of paper. I didn’t even realize it until later. And that’s the kind of level of stuff he plays with.”

Furniture is how Ben Fountain became aware of Coursey. It was long before they actually met, back in the 1980s, when Fountain was a young associate at Akin Gump, working in the law firm’s real estate division. At some point, he noticed a pattern: when someone in his section made partner, Coursey would soon show up.

“Because once you made partner, then you could decorate your own office,” Fountain says. “You had a budget for it. And so it was kind of a rite of passage. If somebody made partner, then about six months later, you’d see Tim Coursey up in the office, moving in this gorgeous, custom-made furniture.”

The tradition began with Steve Anderson, a partner at the firm who had gotten to know Coursey when they were at SMU together in the late ’60s. At first, Fountain didn’t realize that Coursey was the one responsible for making the desks and credenzas and coffee tables, only noting him as “this silent, brooding presence” who was there to deliver it. He was also struck by the fact that the quiet man moved it in by himself.

“He had it compartmentalized, you know, in these very ingenious ways,” Fountain says. “He never looked real happy up there at the law firm, I’ll say that. I think he felt that he was making a raid behind the lines, behind the lines of capitalism, maybe.”

Fountain quit practicing law to work on his writing full-time in 1988, and he didn’t see Coursey again until they crossed paths in 2000. (Coursey, for his part, didn’t remember Fountain from his Akin Gump days. “I’m glad he made something of himself,” he says.) This time around, they became friends. Fountain remembers when they went to Turkey for two weeks in 2010, along with a group of writers and artists from North Texas. It was sort of a cultural exchange program; their cohort was regularly introduced to other artists as they made their way around the country.

“He would always introduce himself as a furniture maker,” says Fountain, who by then knew exactly what the man was capable of. “He would say, ‘I’m Tim Coursey. I’m a furniture maker.’ And so, every once in a while, I’d pipe up and say, ‘Shut up, man. You’re probably the greatest artist Dallas has ever produced.’ But that’s Tim.”

After Coursey started writing, a few years ago, in the run-up to the 2016 presidential election, he eventually asked Fountain to take a look at his stories, steeped with the darkness lurking underneath 1960s counterculture and a healthy dose of modern-day paranoia. (It’s fitting that the riot at the Capitol happened the day before I visited Coursey at his shop; the so-called QAnon Shaman, in his face paint and headdress, might have been a background character in one of Coursey’s pieces.) Fountain often gets asked to read people’s stuff, and though he often accepts, he never expects what he receives to be any good. Even with Coursey, Fountain tempered his expectations. Then he started reading.

“He’s got his own unique style or voice,” he says. “But it goes beyond just style. I mean, it’s the perspective. It’s the habit of mind a writer brings to the world. And you can tell pretty quickly if somebody has an engaged and active mind or if it’s a passive, not very interesting mind. And his is hitting on all cylinders all the time. That’s what you see in his writing. He’s extremely aware of the world and engaged in it at all levels, from the visual through the emotional, psychological. I mean, he’s great on family dynamics. He’s great on counterculture. He’s great on good ol’ American paranoia. I mean, he’s got the whole package.

“So now, it turns out, he might be a genius writer, too,” Fountain says. There is an implied that son of a bitch.

Writing is a natural endpoint for Coursey, a destination he has been headed toward all this time, maybe without realizing it.

“All of his work, his art, tends to bring with it a narrative,” says David Searcy. The author has known Coursey since they were both art students at SMU, under the tutelage of Texas titans Jerry Bywaters and Roger Winter. “There’s some sort of story here. This is a cultural artifact as well as a single art piece, as if it emerged from some sort of culture that we’re only dimly aware of, and only through the clues he chooses to make, sometimes. It always carries a narrative with it.”

It makes sense. Coursey says that he has always had more literary friends than art friends, and much of that has to do with Searcy. In fact, Searcy is probably responsible for many of the art friends, too. Sofia Bastidas Vivar, the Pollock’s curator, met Coursey while she was housesitting for Searcy, taking care of his pets. They struck up a friendship that eventually resulted in Coursey’s exhibition.

You can see where she got her inspiration. Searcy is maybe Coursey’s last remaining gallerist; his home is filled with Coursey’s work. Every room, seemingly, holds a Coursey. There is the pair of vaguely Mission-looking sofas in the living room, with candleholders built into the armrests, and the Shaker-inspired desk in the study. There is an engraving in the bathroom and a piece in one hallway that looks like a murderous catcher’s mitt. The dining room has a group of small bronze statues atop a tiny marble plinth.

“That was a part of a series that he did,” Searcy says. “When he sculpts figures, it’s almost always women, and it’s almost always of a single idealized type. They’re athletic, slightly stocky, and they also always have this tightly curled hair. It’s some kind of ideal.”

Searcy remembers Coursey saying years ago that “every shape he sculpts is based upon the female pelvis somehow. I’m not sure if that still holds.”

Turning to writing now isn’t just a natural endpoint for Coursey creatively. It also suits him physically. He says he is all but done with furniture making.

“The last project that I did will probably be the last furniture project that I ever do, because it damn near killed me,” he says. “I’m no longer able to lift what I build.”

But that doesn’t mean he is going to stop making things. He can’t. He’s been in workshops like this all of his life, and he’ll be in this one for the rest of it. The shop is decorated with the remnants of past projects and gray-green machines that conjure a bygone age. “I have all this equipment that’s inherited from dead people of whom I was fond,” he tells me.

This is where his stories come from.

Coursey gestures toward one of the machines. “That’s about, oh, a pre-World War II, 1930s Montgomery Ward wood lathe,” he says, “which I’m going to use to do these turnings here. This is in progress,” nodding to the wood nearby. “That’s what this junk is.”

“His mind is hitting on all cylinders all the time. That’s what you see in his writing.”

Over there is an ancient, alien-looking drill press, which he says came from Will Hudson, “a quasi-cousin in the Southern tradition,” who got it from his father, Commodore. Hudson, he explains, “found himself with a crippling social conscience, and wound up with the Child Protective Services. And he was assigned the case of a bruja, a witchy woman, whose kids were causing a lot of havoc. They were not that old. And he was going to try to take them away. She didn’t like that. And she supposedly hexed him.”

Some months later, he continues, Hudson went in for a chest X-ray, his first ever. He was 25, or maybe 28. Somewhere in there. Coursey forgets. “And they found a very strange thing in there,” he says. “There’s something called a teratoma. It’s a little monster. It’s a wad of generative tissue that grows. There might be hair and teeth and weird shit in there.”

Doctors removed the tumor, but it was too late. It had metastasized. “But I lay the blame for his demise directly on that bruja,” Coursey says. “Apparently she was quite effective at her job.”

He says this quietly, not because it makes him sad but because he says everything quietly.

Another story: Coursey was working at a picture frame shop in the late 1960s when the owner, an ambitious sort, decided he wanted to be a jeweler. He paid a jeweler to let him apprentice and left his young employee to run the shop. He came back to the shop with a massive debt and a bunch of jewelry-making equipment that Coursey learned to use.

“And then I started making jewelry for all kinds of people,” he says. He empties a tattered manila envelope onto his workbench and sifts through the contents. It’s a stack of old jewelry designs along with a few of the finished pieces. A ring, a couple of pendants, a bracelet, a locket, a pair of earrings. He’s looking for something he deems worthy of showing me, keeping a running commentary as he searches.

Yeah, that’s nothing.

Wedding rings, wedding rings forever.

This is for a woman that married a Haitian for some reason. He was a homeless lunatic, but she was impressed. But she got him into the country. Here.

He shows me one, then changes his mind, pulling it back.

It’s dreck. Trying to find you a good one, and then I’ll give it up. A lot of Celtic influence.

At some point, without my noticing, a small lizard climbed onto the workbench and is now standing on a balled-up hooded sweatshirt between me and Coursey, his forelegs balanced on the hood, his neck craning up toward Coursey like he’s listening. Coursey’s voice is so gentle that the tiny reptile is not spooked.

This is a perfect diamond. It’s the size of a forefinger nail. And these are iron and gold, the stages of the moon. As if knocked into it, brutally hacked into it with a hammer.

At the bottom of the stack, he finds something he wasn’t looking for: why he does all of this.

“I can come up with art-sounding rationales for any and all of it,” he says. “But I think it’s mostly I’m making things in order to show what I can do, and to gain the admiration of my friends, and to generate something that I myself would like to run across.”

This story originally ran in the March issue of D Magazine with the title, “Don’t Call Him a Genius.”

Get the FrontRow Newsletter

Author