In the fall of 2018, my wife and I welcomed home a foster child with the hopes of adopting. He was 14 months old, yet ours was the third home he had lived in since becoming a ward of the state. We fell in love instantly, and we were overjoyed when his biological parents told Child Protective Services that they wanted us to adopt him. But we knew we still needed a lawyer.

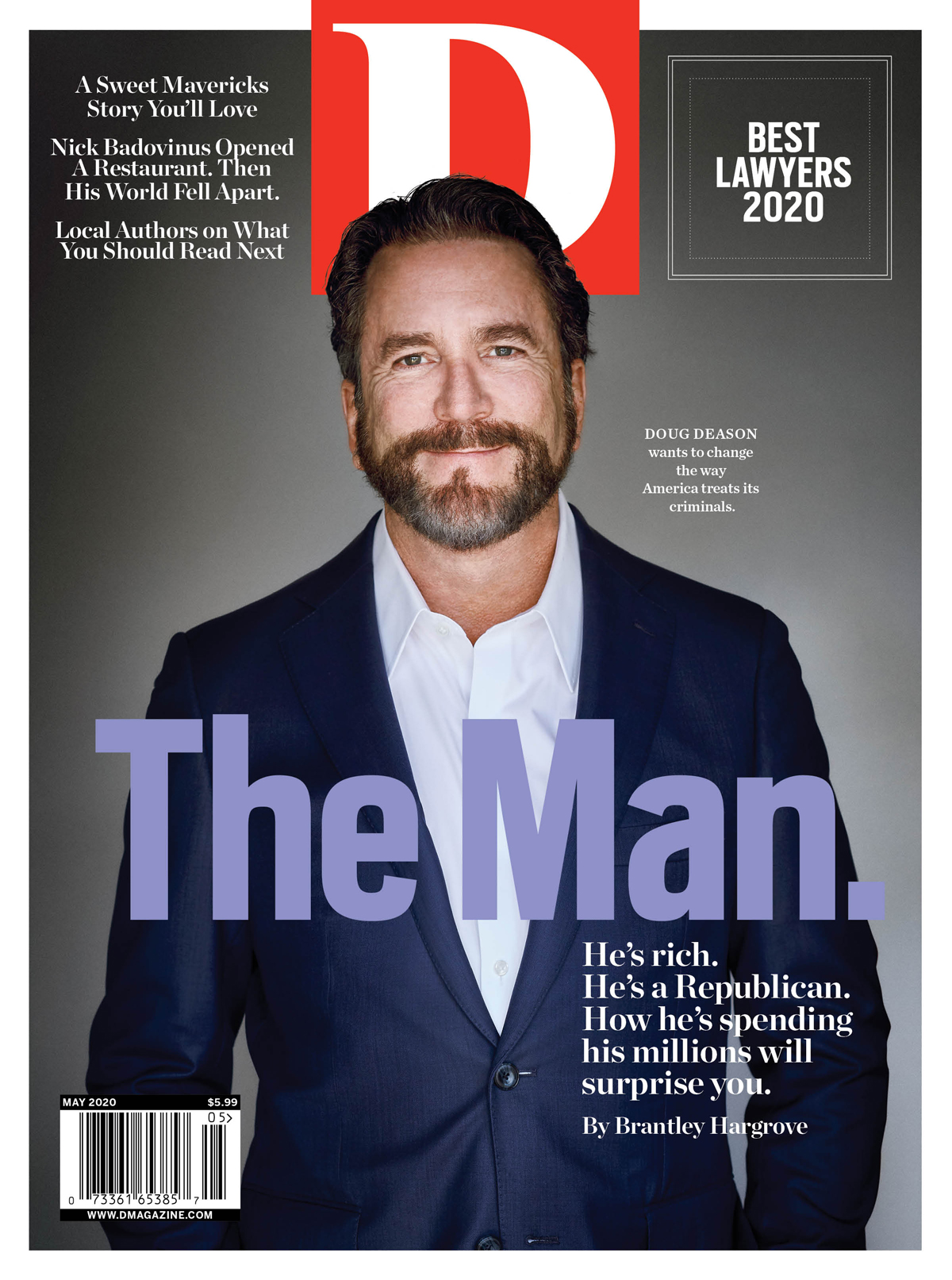

Our adoption agency and CPS directed us to the same man, Dallas attorney J. David Joyce. I remember receiving a letter from his office after we made the initial call and expecting to find the usual boilerplate introduction. Instead, I discovered that we weren’t going to be working with the average adoption attorney. Joyce has 14 brothers and sisters, 13 of whom were adopted. And he and his wife have adopted four of their five children.

If you were a defendant in a criminal trial, the likelihood that your lawyer would have first-person experience as a criminal defendant would be, thankfully, exceedingly low. But wouldn’t it be great if your hired counsel could turn to you, look you in the eye, and tell you he knows just how much is at stake, what it feels like at every step of the process, and exactly how to prevail?

When we hired Joyce to be our adoption lawyer, we came about as close to that scenario as possible.

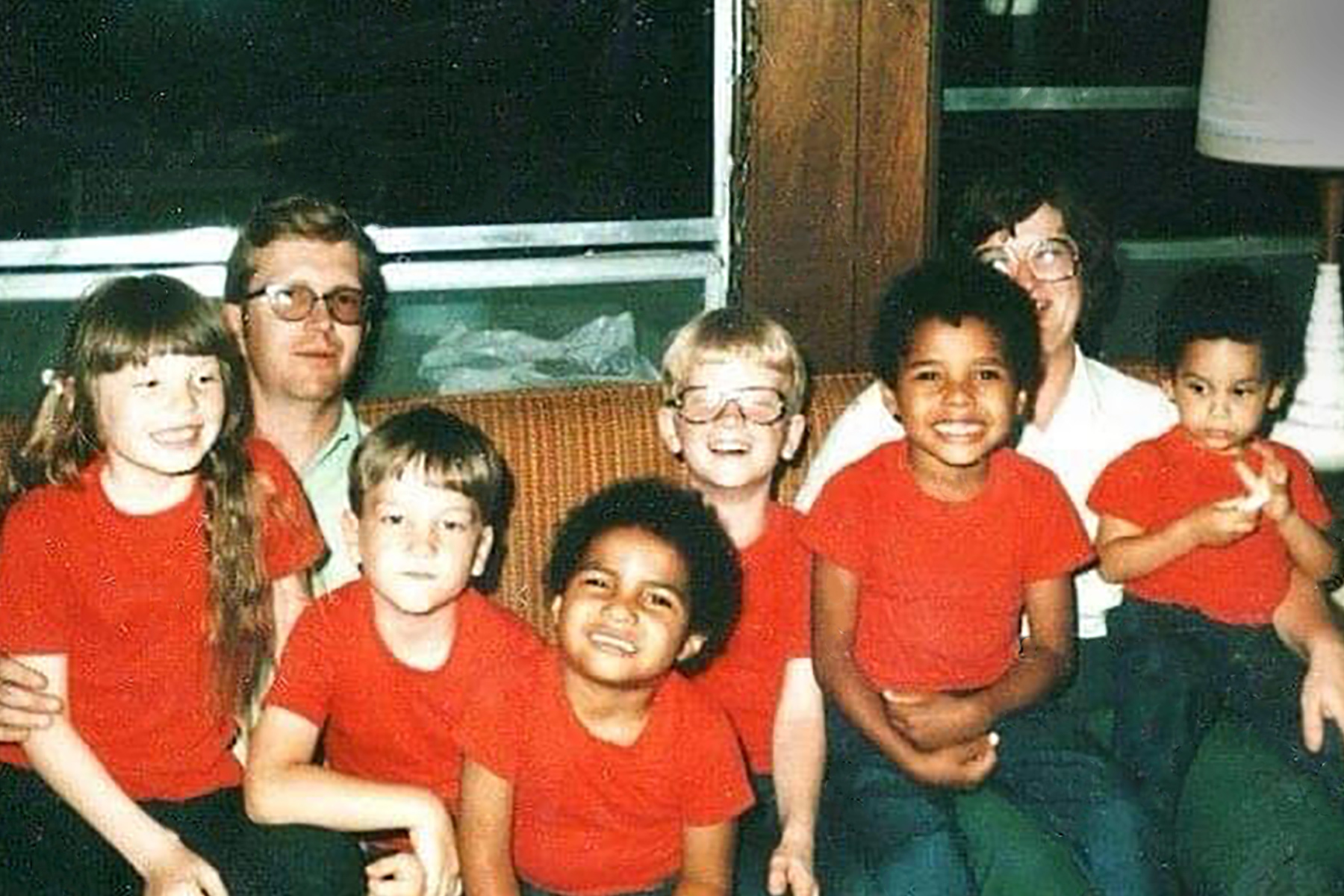

Joyce’s parents married as teenagers and started building their family quickly. Ever since she was a little girl, Joyce’s mother, Suzanne Novotnak, had wanted to adopt. Transracial adoption was illegal at the time in Texas and Oklahoma (it wasn’t federally protected by law until 1994), but the couple were able to adopt a mixed-race girl after Joyce and his brother were born.

The couple would go on to have 10 children, eight of whom are adopted. Novotnak says there was no grand philosophy driving the family’s choices. “The kids that we adopted were kids that needed a family,” she says. “And once they came to our house, they never left.”

But the commitment to serving children in need took a toll on their marriage, and the couple divorced when Joyce was a teenager. Novotnak, who started a special-

needs adoption agency in Oklahoma, went on to adopt five more children after the divorce, bringing the total to 15. The children were a mix of white, black, Hispanic, and Native American. Many were adopted as older children and had experienced great trauma.

Novotnak says that from the start, Joyce was a fan of the underdog, with a welcoming spirit that was open to his new brothers and sisters. “Every time we brought home another child, he was the first one to welcome them to be a part of the family,” she says.

In college, Joyce studied linguistics with the hope of becoming a Bible translator. But after moving to North Texas with his wife, Sherry, he changed his mind and decided to go to law school at SMU. Nothing really ignited his passion, and after graduation he found himself unhappily working in the insurance field. Despite his background, family or adoption law never crossed his mind.

Joyce’s wife, however, was a social worker for an adoption agency at the time. When one of the children on her caseload was rejected from a potential home while his three siblings were adopted, the couple felt compelled to make a move. Their son was 10 years old when he arrived at their house, already old enough to be considered difficult to adopt.

Still, it wasn’t until a friend told Joyce over lunch that he should be using his legal skills in the adoption arena that he had his epiphany. Rather than join a larger firm and work for a few years before starting anything on his own, he decided to hang his own shingle and get to work. He met with judges, worked the social services network, and told his personal story to anyone who would listen. It worked.

From the start, Joyce was a fan of the underdog, with a welcoming spirit that was open to his new brothers and sisters.

He now has a robust practice, handling the adoptions of 300 children per year, most of whom are placed in Dallas County through CPS custody. For perspective, a total of 327 adoptions were finalized in Dallas County in 2019. The majority of Joyce’s adoptions go smoothly, and he doesn’t spend too much time arguing cases in court. But the occasional contested case can make for a heart-wrenching and emotional roller coaster.

While heidi and jon Button’s adopted daughter was still in the neonatal intensive care unit, the child’s biological parents left the hospital and never came back. When it was time for her to be released from the NICU, the Buttons received a call from Dallas County CPS saying it had a child in need of a home. Joyce helped the couple with the uncontested adoption, and things went well. But later, when a boy in Denton County was placed with the Buttons and the case became problematic, they decided to employ a Denton lawyer to handle the trial.

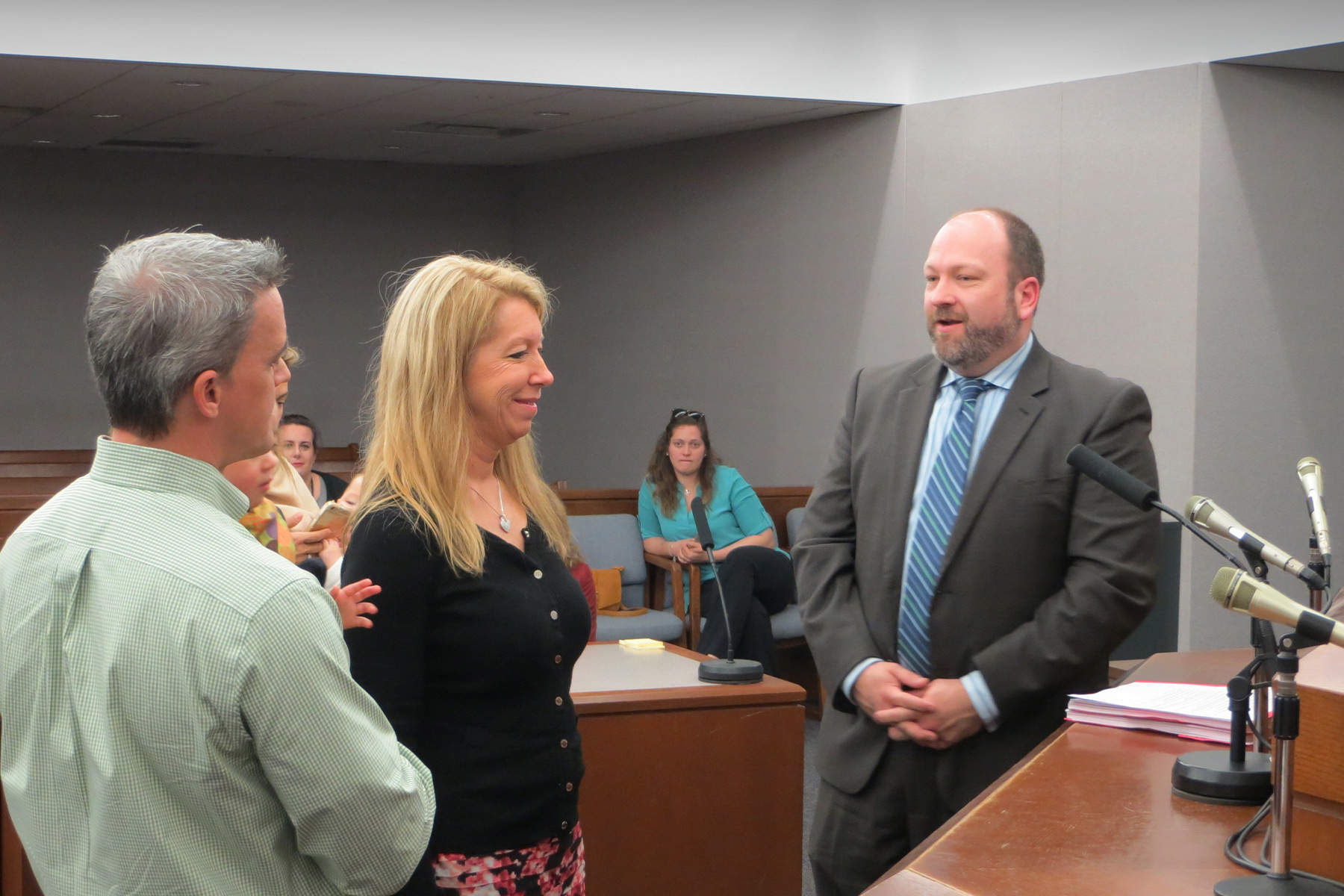

The case became complicated and a private investigator got involved. After the couple had spent tens of thousands of dollars in attorney’s fees, a mistrial was declared. Facing the daunting prospect of a second trial, the Buttons reached out to Joyce, and he put them at ease. “I called David, and he goes, ‘You go to court, you show up, and you win.’ He didn’t make this about anything other than the children, which is what it’s supposed to be about,” Heidi says.

Three years and two trials after their son first entered their home, the Buttons officially added him to their family. For Heidi, Joyce’s history was essential to his success. “He was able to take that personal experience and credibility and be effective in the courtroom.”

Joyce can connect with his clients and a judge in a way most lawyers can’t. “When I make an argument to a judge or a jury, it is going to be believed and heartfelt,” Joyce says. “I don’t fight just for the sake of fighting. Some lawyers are really good at that. That’s not me.”

Joyce’s story became even more compelling when he adopted three of his struggling sister’s children while he and his wife were already raising a daughter of their own. They didn’t adopt to make his practice more successful, but Joyce says it helps his credibility. “It’s not just a job for me,” he says. “I live it.”

Just as he has continued to expand his own family, Joyce knows that many of the parents he works with have a heart for the overwhelming number of kids in need, and they will be calling his office again. When he leaves the courthouse after finalizing an adoption, he tells everyone that he will see them next time. “Sometimes I don’t,” he says. “But oftentimes I do.”

I have a feeling that my family will be one of those he sees again.