On a hedgerow-lined Preston Hollow street, Doug Deason waited for his guests to arrive. By 6:30 on a sweltering September evening in 2014, they began to stream through the wrought-iron gates and up to the valet as the men and women who would soon run the Texas government milled around tax consultant G. Brint Ryan’s three-story, 20,000-square-foot Strait Lane home. Even the doghouse was decadent. The family Cavapoo and Peekapoo had their own scale model of the mansion, complete with Ionic columns and air conditioning.

Everyone at the fundraiser—the givers and the politicos—knew Doug’s dad, Darwin. A big-dollar Republican benefactor, Darwin is one of Dallas’ most colorful bon vivants, spending as much as half of the year aboard his 205-foot yacht Apogee. Now single, Darwin has been married at least six times. He made his money selling a computer services business to Xerox.

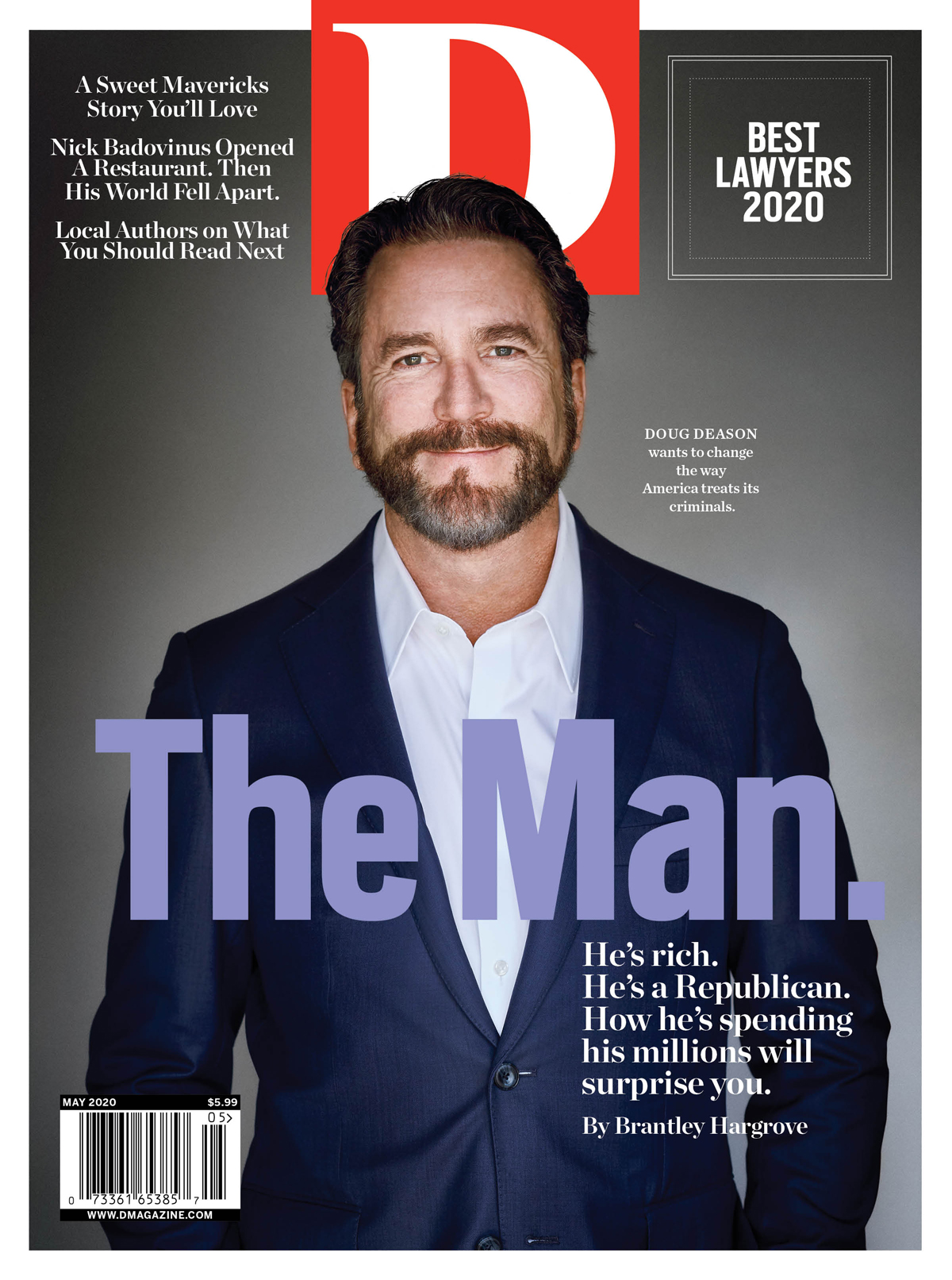

Doug, on the other hand, had for the most part worked in quiet corners of his father’s business services, construction, and data processing empire. Easygoing and affable, with a voice tinged more by the Ozarks than the Park Cities, he seemed like a more laid-back version of Darwin. But get him going on welfare (“Women are incentivized to have babies out of wedlock, for example, with different fathers.”) or even government laboratories (“The U.S. should not be in research. We should sell our labs to private industry.”), and some of that Deason intensity would blaze through. Only through capitalism, he argued, could the poor lift themselves out of poverty.

His own path hadn’t exactly been bootstraps. After college, there was no question where he’d eventually end up: at his father’s side, ringing the opening bell at the New York Stock Exchange, taking a company public. Hundreds of millions in revenue became billions. Doug, meanwhile, managed the family office.

Now, though, the boss’s son had begun to emerge from Darwin’s shadow, making his own way through the state and national Republican donor scene. “It’s not like I love politics,” he protested. And yet the walls of his office were crowded with photos of him posing with presidents and red-state governors.

Now, in Ryan’s great room, with its coffered ceiling, Doug stood at the center of a gathering he’d organized for the county GOP as a member of its finance committee. With help from Ryan, the finance chair, they’d managed to wrangle just about every incoming Republican statewide, along with a passel of local candidates and a few North Texas congressional incumbents. That meant nearly the entire future Texas executive branch had schlepped north at Doug’s invitation to make a withdrawal from Dallas’ electoral ATM.

The event itself, however much it felt like a passing of the torch, was largely beside the point; there would be more just like it. Doug had to admit that it was cool to text the governor, but the real question before him that evening was what he should do with this bounty of political gratitude. “I’ve got every single statewide elected official’s cellphone number and I know them personally,” he said. “That’ll probably last two weeks.” He was being modest; in truth, Deason-level access doesn’t have a short shelf life. And that’s what this would all come down to: access and what can be done with it.

This was the day Doug decided to use his good fortune to help the kind of felon he might have been in another life. The charges back then were overblown. But what if he hadn’t been a Deason? Doug is the rare ultra-rich conservative white guy willing to admit that life might have turned out differently had he been born, say, a black man from a South Dallas neighborhood with a high incarceration rate.

Long before the yachts and sprawling penthouses, there were chickens. Acres and acres of chickens. Northwest Arkansas is prime chicken country. Doug grew up around the business; both sets of grandparents raised chickens.

Darwin’s path from coops to IBM punch cards has been described often enough now that the familiar contours have assumed a kind of origin-story mythos. He borrowed $50 from his dad and split town; toiled in the mail room of Tulsa’s Warren Petroleum; took night classes in programming; moved up to the computer room; and resigned shortly after his five-year anniversary because the boss’s boss handed his anniversary pin to someone else and called Darwin “Bill.” Then it was off to Dallas and the ground floor of a startup called Affiliated Computer Systems. Darwin climbed the ladder from salesman to VP to president. ACS became the largest bank data processor in the country. If you’ve ever cashed a check or paid child support, ACS probably got a piece of it. The company went on to pioneer off-site ATM banking and became the largest such network in the world.

Less well told is Doug’s place in this tale of ambition and ascendancy. His parents divorced in 1968, when he was 6. Doug sobbed into the rear window as he, his brother, and his mom pulled away from their gingerbread house on Tulsa’s Indianapolis Avenue. They were headed east for Rogers, Arkansas; Darwin south to Dallas to chase his dreams. Doug was devastated, his entire existence upended.

But this new double life turned out to have its advantages. In one world, he was hunting, fishing, shoveling chicken shit, and stocking shelves in his grandfather’s butcher store. Sam Walton, the founder of Walmart, was always coming in, sometimes with his daughter, Alice. He spent his summers in the other world, shopping at NorthPark, sliding down the planters in front of Neiman Marcus, and going to Six Flags with his dad and, Doug says, “his secretary or wife or whoever he had at the time.”

Flash forward to high school. Doug liked to party. His buddy’s dad, a Walmart executive, got transferred, leaving behind a fully furnished house with a well-stocked liquor cabinet. This buddy gave Doug a key, with the admonition to keep any gatherings small; the neighbors would be keeping an eye on things. The arrangement worked out fine for a few weeks, until word got around. In Doug’s retelling of the fateful evening in question, he was sitting on the couch with his girlfriend, in the midst of an unplanned rager. Smelling trouble, Doug beat a quick exit. As they were backing down the driveway, a police cruiser blocked them in. Doug and the other boy with a key took the rap. He called his mom later that evening from the Benton County Jail. Felony burglary, he said. She freaked out. Doug shrugged; he didn’t really know the difference between a felony and a misdemeanor. Besides, he was out the same night.

“There was no chance in hell we were going to support Hillary.

Doug Deason

The following Monday, his mom called city attorney and future drug czar, congressman, and governor Asa Hutchinson. As the office manager for an architectural firm that did a lot of work for Walmart, Bonnie knew powerful people in Bentonville as part of her job. Hutchinson told her to relax. He’d get the charge reduced to criminal trespass, a misdemeanor. At worst, Doug would spend his last summer of high school on probation instead of drinking beer and getting high with his buddies at Beaver Lake.

The result could have been finagled by any lawyer cruising the courthouse for clients. But because of who Doug was—white, college-bound, from a connected family—his troubles got smoothed out at the top. The way a charge like that could have changed a young man’s future didn’t really sink in at first. Then Doug applied to college. SMU and University of Arkansas (where he ended up) both asked about felonies during the application process. Still, Doug remained a callow youth who didn’t fully grasp his good fortune. To wit: his sophomore year at Arkansas he left a party with “a pretty good buzz on” and got pulled over for speeding. A DUI arrest looked inescapable. Instead, the officer took pity on the nice college boy, wrote him a ticket, and insisted on following him home.

Doug forgot to pay the ticket.

The officer showed up at his door 30 days later and arrested him. He was out that evening, after his brother raised enough money to pay the fine. Doug continued chipping away at his computer science degree without further incident and applied for a part-time job at IBM. Once again, the application asked about felony convictions. It was yet another box Doug Deason wouldn’t have to check.

In the fall of 1984, Doug graduated and moved to Dallas to work at a commercial real estate firm. The felony question appeared again during the hiring process. Even the contract he signed for his first cellphone asked about his criminal record. At every step, it seemed to Doug that some form of participation in society was off-limits to those who’d already paid their debt in full. Not that there was much he could do. He was the new guy getting his start in a commercial real estate market that was about to get hammered by the savings and loan crisis.

Eventually, though, Doug found himself at the helm of the Affiliated Computer Services commercial construction enterprise, Precept Builders. During his tenure there, Doug hired a man named Dondi Wafford, despite the background check that turned up a felony. Wafford was black, raised in Oak Cliff by a single mother who worked two jobs. His father hadn’t moved to another city chasing his fortune—he was just gone. A high school dropout, Wafford was dyslexic at a time when segregated Dallas schools didn’t have special-needs programs. He fell in with a bad crowd, got into drugs, and started stealing. Unlike Doug, his attempted felony burglary charge actually stuck.

The best way to describe Wafford’s work for Doug was as his body man. Wafford ran errands and worked as a driver. The better they got to know each other, the more Doug was discomfited by the way the system trapped those who couldn’t afford the cascading consequences. In Wafford’s case, not long after his arrest for the first and last felony he’d ever commit, he was broke, with no education and a felony conviction disqualifying him from renting an apartment or landing a job that didn’t break his back. Unable to pay his probation fees, he skipped a few check-ins. A warrant went out and he spent nearly two years in prison.

“It really was an eye-opener to hear how it works,” Doug says.

When Darwin closed the deal with Xerox for the sale of Affiliated Computer Services, in 2010—netting a reported $800 million in cash and stock—Doug moved over to the family office to manage the windfall and brought Wafford with him. Apart from family, there was no one he trusted more. Wafford often picked up Doug’s kids from school. He had the keys to Doug’s house. And yet if this man, now in his late 50s, ever needed a bed at an elder-care facility, the felony he’d committed when he was in his early 20s could very well keep him out. He could be deemed a risk to other residents. “It’s just absolutely absurd,” Doug says.

The criminal justice system could be downright accommodating for people with money and connections. Doug never met a consequence he couldn’t dodge. But for those like Wafford, the system would never fully turn them loose.

In June 2012, while sitting in a ballroom at the Park Hyatt Aviara, a tony oceanside resort in Carlsbad, California, Doug believed he found a way to change the system. At the dais stood Charles Koch, the billionaire industrialist whose libertarian donor network had created what is essentially a third major political party made up of the 0.001 percent. Koch hosted regular seminars, consortia for the super rich, events where plutocrats would gather at swanky resorts to discuss elections, tax cuts, and how to roll back social services and environmental regulations. Attendance, by invitation only, had grown since the election of President Barack Obama and was conditioned upon annual donations of at least $100,000. Most of that would get disbursed among an alphabet soup of Koch-controlled political organizations and think tanks. In a sign that Doug had arrived among the ranks of conservative power brokers, he’d recently received his first invite.

He had much in common with Koch, as it turned out. Besides both being scions of successful businessmen and simpatico in their contempt for the social safety net and federal regulatory state, they shared something else: a conviction that the criminal justice system was unjust. For Koch, the belief dates back to one of the most significant prosecutions for environmental crimes ever brought under the Clean Air Act. The 97-count federal indictment charged Koch Industries in 2000 with venting 91 metric tons of benzene, a potent carcinogen, into its Corpus Christi refinery’s waste streams. Koch’s lawyers accused the government of prosecutorial overreach. But the company ultimately agreed to pay $20 million in fines and restitution, and pleaded guilty to covering up environmental violations by falsifying documents.

After that, Koch and his organizations started speaking out against “overcriminalization” and making donations to the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers’ “white-collar crime” projects. Reformers viewed this new advocacy with intense skepticism; Koch-affiliated think tanks like the Heritage Foundation seemed less interested in championing the downtrodden and imprisoned than in securing mens rea reform, Latin for “guilty mind.” Inserting mens rea into the criminal code for, say, environmental violations could make it nearly impossible to prosecute a business owner for improperly disposing of 91 metric tons of benzene.

Ensconced at a resort reserved that weekend for the exclusive use of the network, Koch described ways to restore compassion to a system he saw as excessively punitive. That’s how Doug recalls it anyway; only a few times have recording devices been snuck into these seminars. But it does sound an awful lot like the earliest road map for how the influence of the Koch network would soon be wielded to press lawmakers at the state and federal levels for some of the most sweeping changes to criminal justice policy since the ’90s. If Koch was on the level, what this represented was the wholesale realignment of the national conservative establishment. Less Code of Hammurabi, more New Testament.

Doug felt himself getting emotional, tearful even. With all this talk about second chances, he wondered whether Koch had been told about Doug’s experience in advance of the meeting. It felt like he was speaking directly to him. “He’s laying out in front of me the opportunity to do with them what I’ve always wanted to do,” Doug says. “I just didn’t know how to do it.”

What Koch proposed was novel in its scale. But some of the particulars had already been tested elsewhere, most notably in Texas. In the mid-aughts, the state faced a decision: spend huge sums expanding the prison system or change its policies to reduce admissions and get more prisoners out the door. The buildup of the Texas prison population had been a bipartisan effort spanning decades. Being the first state to pass a three-strikes law hadn’t helped matters. The courts were trying many juveniles as adults, and probation revocations were up while paroles were down.

Gov. Ann Richards, a Democrat, presided over the addition of about 100,000 prison beds in the early ’90s. George W. Bush picked up the baton with the construction of 38 new prisons. When Rick Perry was elected, the prison population had quadrupled since 1980. Instead of tackling the root causes that gave Texas the country’s highest incarceration rate, he used a 2003 budget crunch as an excuse to cut drug treatment, probations, and education programs for prisoners, the remedies that might have slowed the prison system’s revolving door. That was the same year Republicans took control of the Legislature for the first time since Reconstruction. They could no longer sit on the backbench, shooting tough-on-crime spit wads while the Democrats governed. They had a state to manage now. But Perry vetoed subsequent attempts by the Legislature to address the crisis.

Then, in 2007, the number crunchers projected a demand for 17,000 new beds at a cost of $2 billion. Bills Perry shot down in the previous sessions he now signed. The 2007 raft of legislation funded halfway houses, mental health resources, drug courts, and drug treatment beds. In place of revoking parolees for first-time, low-level violations, the state built “intermediate sanction facilities” where offenders would be sent to cool off for a few months rather than the next 20 years. The prison population’s runaway growth flattened out and even fell a little. Texas didn’t end up building new prisons. In fact, in a few years, it would close some.

Texas still had the country’s highest incarceration rate. Other states had recently tackled more aggressive reforms, reducing their prison populations. A Connecticut success story, however, didn’t have quite the same ring. Texas was a more salable poster child for how even the country’s most lock-’em-up state could enact sensible reforms. By rebranding as both redemptive and budget savvy what in a recent era would have been tarred as soft on crime, Texas had created a blueprint for other red states to do the same. The “Texas model” only became more popular during the recession, when states everywhere were taking hard looks at their shrinking budgets and spiraling corrections costs. And with the high-profile killings of unarmed black men like Michael Brown and Eric Garner, public sentiment toward prisons and policing had begun to shift; tough-on-crime demagoguery didn’t sell at the polls the way it used to. Conservative thought, meanwhile, was taking on an increasingly anti-government flavor.

At around the same time, Koch Industries became a financial supporter of the Texas Public Policy Foundation, now the brain trust for conservative reform in Texas. Newly flush with donations, TPPF representatives took the Lone Star approach on the road. The national campaign, called Right on Crime, enlisted a lineup of unimpeachable movement leaders like Newt Gingrich, Erick Erickson, and Grover Norquist to vouch for Texas-style reform.

The brilliance of Right on Crime’s ideological framework was in how it countered threats to the conservative identity. These policies weren’t a repudiation of the old beliefs. Republicans could still be tough on crime while enacting reforms “grounded in time-tested conservative truths” like limited government, personal responsibility, “conserving taxpayers’ money,” reducing recidivism, and halting the criminal code’s encroachment on “economic freedom.”

Not mentioned: the deeper systemic explanations for the prison system’s expansion and its disproportionate impact on communities of color. But this, longtime observers of state policy say, is how reform finds purchase in a red state. “This is about the messengers,” says Scott Henson, founder of Grits for Breakfast, the influential criminal justice policy blog read by Texas conservatives and liberals alike. “Who’s the right messenger? The black liberal arguing about racial disparities or the GOP think tank saying, ‘Here’s how to pragmatically manage the system and reduce incarceration rates’? These reforms do disproportionately help black folks. But if you frame it that way, we might not be able to pass them. So we don’t.”

As with climate change, scientists could throw data at conservatives all day and succeed only in making them more suspicious. The message had to hit the right notes and come from someone they trusted.

Doug Deason was the right kind of messenger.

Texas still had a lot of work to do. And beyond the annual $150,000 to $200,000 Doug and Darwin chipped in to the Koch network’s efforts, Doug himself hadn’t gotten personally involved with criminal justice legislation. But with the successful 2014 fundraiser under his belt, he saw an opening and decided to act.

That November, Doug and Mike Hasson, the Texas director of Americans for Prosperity, the Koch-funded issue advocacy group and an organizing force behind the Tea Party, steered south of Interstate 30 for a Section 8 apartment complex. This part of town was only 10 miles away yet couldn’t have felt farther from Preston Hollow. If anyone understood with case-by-case granularity how the system made life after prison as difficult as possible, it was Tina Naidoo, executive director of the Texas Offender Reentry Initiative.

As they settled into Naidoo’s office, Doug said he wanted to know what was holding Naidoo’s clients back and how he could help. She laid out the mission. Whether it’s helping the recently incarcerated with a drug problem, securing housing or employment, or reuniting them with their estranged families, her organization sought to reassemble lives fractured by prison. “We see clients with anything from a first-grade education to a master’s degree,” she said, “but they all have the same issue with employment because they have the criminal background.” It was the same with housing. Her clients were systematically ostracized from what they needed to succeed.

After the meeting, Doug and Hasson huddled in the parking lot. Doug was more certain than ever: he wanted to get a bill passed during the upcoming session, starting in less than two months, that would expunge the records of low-level, nonviolent offenders. Hasson didn’t want to throw cold water on a man now burning with the fervor of a righteous reformer, but he had his doubts. It was a bit late to get anything passed next year. Maybe even the year after. But Doug had money. “He was a large donor who’d never asked for anything,” Hasson says.

Hasson put Doug in touch with Justin Keener, a political consultant and lobbyist. Keener brought the cold water. “You’re not gonna get expungement,” he said. Forcing employers to ban the box on job applications was a liberal’s reform. Consider their target audience, the conservative lawmaker in a cherry-red district, wary of ducking soft-on-crime accusations lobbed by a primary challenger from the far right. The solution itself couldn’t simply be good and just. It had to feel conservative, too, something like an order of nondisclosure that an ex-offender could obtain at the discretion of a judge.

Within days, Keener arranged a meeting in Doug’s office with Brooke Rollins, the president and CEO of the Texas Public Policy Foundation; Marc Levin, Right on Crime’s top guy; and Hasson. Keener laid out an aggressive (and expensive) campaign plan that would entail hiring lawyers, lobbyists, PR people, and policy development experts. But Doug couldn’t just sit back and watch. They’d need his story and his pull. “This isn’t the type of thing you can just write a check for,” Keener cautioned. Doug would have to hit the halls of the Legislature. It could take two or three sessions. Things move slowly down in Austin.

The team began drafting the bill and recruiting sponsors. Whether they were Democrats who saw the prison system empty entire neighborhoods in their districts of young men or Republicans who wanted the law to show a little more Christlike compassion, Doug and his team deployed a tactic liberal and conservative activists alike had been using to get reforms passed in the Texas Legislature for more than a decade. The House and Senate bills—authored by a Democrat and a Republican, respectively—couched the same nondisclosure legislation in different philosophies. In the House, it was the “second chances” bill; “redemption” in the Senate.

“I have a savior in Christ,” said Charles Perry, the Lubbock Republican and Senate author. “He’s a second chances kind of guy.”

Doug was up at 3:45 am most Mondays or Tuesdays to catch the first flight out of Love Field to Austin, where a full schedule of lunches, dinners, testimony, and meetings awaited him. He regaled legislators with the story of that Walmart executive’s house so many times that he got sick of hearing it himself.

He says he nearly lost his Senate author after a local prosecutor got in his ear. Doug called in a favor with one of the senator’s heroes, Rick Perry, whom Darwin and Doug occasionally took to Cowboys games. Perry phoned the senator and gushed about the redemption bill, making his day and, in the process, pulling him back from the brink.

The prosecutors came for the bill, as they did most reform-minded legislation. Even Mothers Against Drunk Driving vowed to oppose them unless they excluded DUI convictions. Doug says they ended up supporting a later version once a manufacturer of car-ignition breathalyzers—and a contributor to MADD—managed to carve out an exception for people who used its devices.

At least $300,000 of Doug’s money later, the watered-down compromises and strike-throughs that ended up getting signed by Gov. Greg Abbott weren’t exactly the stuff of his wildest dreams. The law would apply only to those convicted of first-time, low-level misdemeanors. It wouldn’t help Wafford, and it wouldn’t have helped Doug if he’d caught that burglary charge. Concealing the felon’s scarlet letter was still a nonstarter in the Texas Legislature.

For those who did qualify, most employers wouldn’t be able to see their criminal records, but financial institutions would. Even someone fully qualified under the law could still have his or her nondisclosure petition rejected by a judge. “It was a good learning experience,” Doug says evenly. “You’ve got to bite it off in increments. You got to go in and ask for more than you know you can get, so that what you end up with hasn’t been whittled down to where it’s totally irrelevant.”

Getting a bill passed in a single session was an unusual feat. And the law would help people, if not everyone he had hoped. But Doug didn’t walk away from the process disillusioned. In fact, he became something of a fixer for criminal justice legislation, opening doors that would have remained closed to the usual reformers. An activist with a left-of-center Texas organization spoke highly of him to me, but only on background: “There was information that the governor’s office had a misunderstanding about [the debtor’s-prison bill that would allow judges to waive some fees for the indigent]. Deason called the governor’s office and was able to get someone on the phone. It was at risk of being vetoed.”

Even if it was just a matter of flying down to Austin and filing a card in support of a bill, Doug’s name made a difference, the activist said. “He shows up.”

Doug’s next investment was straight from the Koch playbook. In 2016, Doug, Darwin, and the Charles Koch Foundation pledged $7 million to found the Deason Criminal Justice Reform Center at SMU, where the next crop of prosecutors might emerge with more broad-minded attitudes about crime and punishment. Now the kid from Arkansas chicken country would have an organization bearing his name at the flagship university of the Park Cities set.

At the Deason Center, law students would learn the Right on Crime approach and participate in indigent defense programs. It is worth noting that the center’s inaugural director, Pamela Metzger, leans hard left. “So many SMU law grads become prosecutors, DAs, and defense attorneys all over the country,” Doug says. The old guard might cling to its ways, but the next generation could usher in a new philosophy at the courtroom level. In addition to molding SMU law students, Doug expects the Deason Center to “impact policy, not just come up with beautiful white papers that other academics read and then file away.”

That was step one in what a Koch Industries executive VP once described as the “structure of social change.” The Koch model was intended to transform university departments from the inside out by installing professors who subscribed to a libertarian strain of Friedrich August von Hayek-esque free-market economic thought. They’d influence young minds and generate the academic papers that serve as the grist for think tanks, which the Kochs also funded. The think tanks would then turn this grist into policy. Lastly, “citizen activist and implementation groups” like Koch-backed Americans for Prosperity would take up the policy by synchronizing grassroots and lobbying efforts in D.C. and state legislatures.

The same strategy was being brought to bear on reform, only with less apparent self-interest. Right on Crime (for which Doug was now a financial supporter) fanned out across the country, taking Texas model policy into D.C. and red-state legislatures. Meanwhile, an unprecedented bipartisan effort began to coalesce around what appeared to be a rare opportunity for progress.

Groups from across the political spectrum—like the MacArthur Foundation, the liberal Center for American Progress, the Charles Koch Foundation, FreedomWorks, and Right on Crime—launched the pro-reform Coalition for Public Safety, the public face of the new consensus. Bipartisan summits brought together the likes of Doug and progressive CNN political commentator Van Jones. At an event at the Dedman School of Law, the two quite literally reached across the political chasm to join hands on the only issue about which they did not vehemently disagree. It was easy to see why liberals would latch on as though it were a choice between gripping the tail of a python or tumbling into an abyss. Reform was the impossible dream in a gridlocked era. Congress couldn’t even agree to fund the government. And yet here was an alliance that rendered reform not just imaginable but also politically doable.

Starting in 2015, bipartisan federal legislation even started popping up on everything from reducing mandatory minimum sentences to increasing the use of home confinement and community supervision, echoing many of Right on Crime’s prescriptions. The bills didn’t get far with a presidential election looming. A mens rea provision in the House reform package was a poison pill for Democrats, who saw Koch fingerprints all over it and dubbed the bill the White Collar Criminal Immunity Act. Without mens rea, however, many conservatives pulled their support. Sen. Ted Cruz, not to be out-demagogued by Donald Trump, his rival for the presidential nomination, condemned ideas he’d recently supported. Outspoken opposition in the Senate, from Republican hardliners like Tom Cotton and David Perdue, effectively stalled progress.

Reform still had a long way to go. But the flag had been planted. For the first time in a long time, reformers had reason to hope.

At least it briefly looked that way, until Trump clinched the GOP nomination in late May 2016. The Apprentice host had surrounded himself on the campaign trail with a who’s who of retrograde lawmen. Jeff Sessions, Trump’s earliest Senate supporter and likely pick for attorney general, had spearheaded the effort to kill bipartisan reform bills and had supported legislation in Alabama to make a second weed-trafficking conviction a capital crime. None of this appeared to bode well for the reformers.

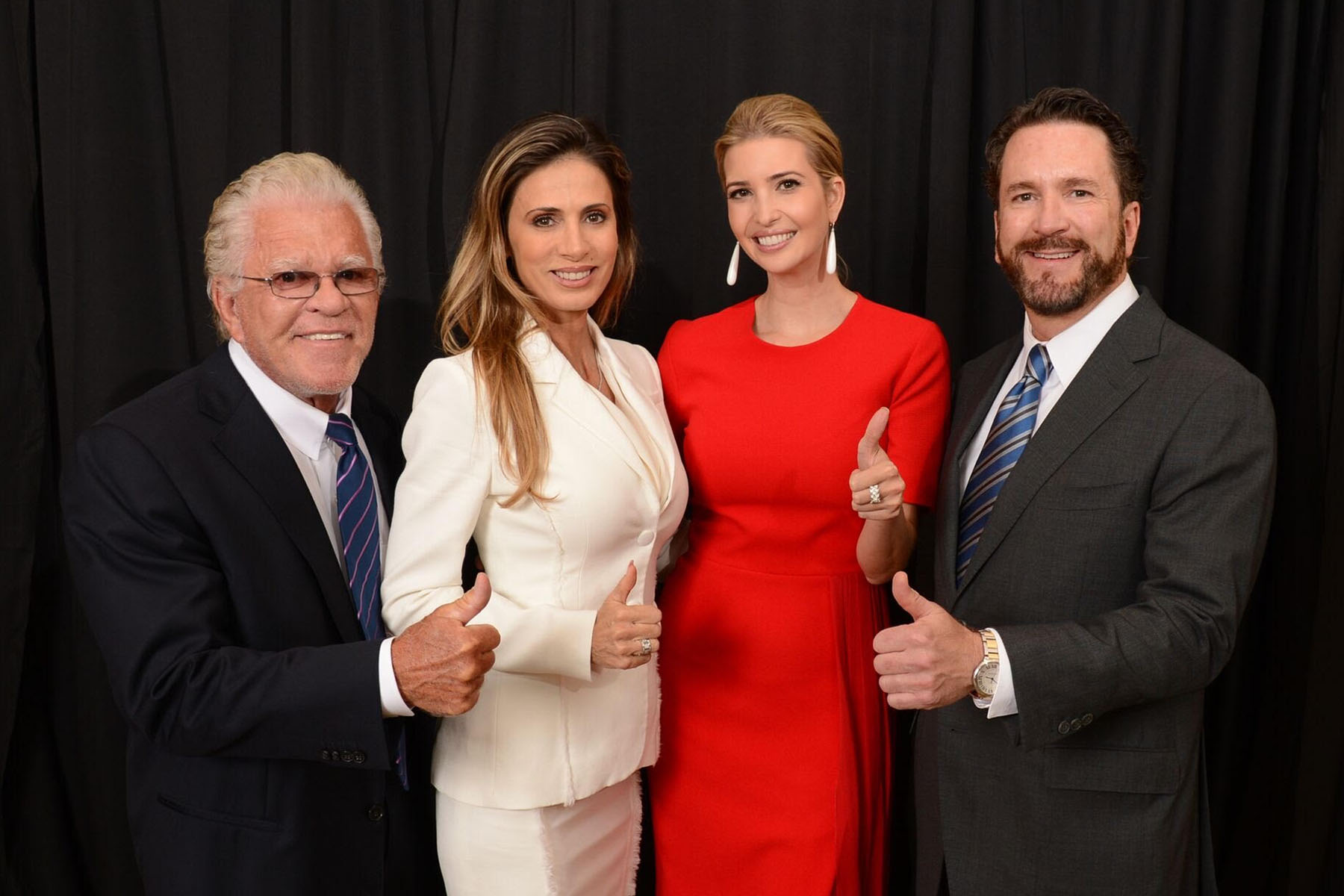

Which is why Doug’s and Darwin’s early support for Trump seemed so strange. In fairness, first they were for Rick Perry. Then they were all in for Ted Cruz. But when they dropped out, Trump was the default. “Because, you know, there was no chance in hell we were going to support Hillary Clinton,” Doug says.

The candidate was in Dallas in June when Doug and Darwin got some one-on-one time with him at the Hilton Dallas Park Cities. Reform never came up, but the scion of a real estate developer from Queens made a favorable impression on the scion of a tech entrepreneur from Arkansas. Doug wasn’t greeted with the clownishly brash Trump he’d recently seen at a rally at the American Airlines Center. In a more intimate setting, Trump was “just the most perfect gentleman,” Doug says. After 45 minutes alone with him, Doug and Darwin were prepared to contribute $1 million, maxing out the federal limit and directing the rest toward the super PAC of a candidate who’d previously blasted the donor class and vowed never to take any of its money. Doug and Darwin were now the first “presidential trustees” of the Trump Victory Fund. Doug urged Koch to get off the sidelines and pitch in.

He did get a chance to quiz Trump about his views on the justice system at later campaign events. What he claims Trump said seems at odds with a candidate whose rhetoric was spackled with law-and-order notes of Nixon and Goldwater. Doug says Trump told him he believed people who broke the law should be punished but that it shouldn’t hang over their heads for the rest of their lives. It was vague, but this unformed quality was probably the most promising part for Doug. Trump didn’t have a criminal justice policy yet. There was still time to help him come up with a good one.

But after the election, reform bills didn’t get much traction, either because they were viewed by Republicans as too soft on crime or by Democrats as too tepid. So far, Trump had offered no leadership on the subject.

Doug did have at least one ally in the White House: Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law and adviser. Kushner’s father, Charles, had spent 14 months in prison for tax evasion, witness tampering, and making illegal campaign contributions. Those familiar with his thinking say the younger Kushner saw a system that cultivated better criminals, not rehabilitated them. And there was something ludicrous to Kushner about his real estate developer father residing in a New Jersey halfway house on the taxpayer dime, says Right on Crime’s Levin.

Now heading up the newly formed Office of American Innovation, Kushner placed criminal justice reform high on his agenda. Doug asked to be his adviser on the subject. Kushner charged him with rounding up conservatives with reform experience for a “listening session” in September 2017. Doug invited Mark Holden, Koch Industries’ general counsel and point man on reform issues; Brooke Rollins, Texas Public Policy Foundation’s president and CEO; Kansas Gov. Sam Brownback, representing a red state that had enacted reforms (although its prison population had continued to climb); and Rep. Doug Collins of Georgia and Sen. John Cornyn, who had authored reform bills. Doug says Kushner decided to keep deliberations close and among conservatives until they had something to announce.

“You’ve got to go in and ask for more than you know you can get.

Doug Deason

This is how the Texas contingent took over criminal justice reform in the Trump White House. By February 2018, Rollins had officially resigned from TPPF to become the assistant to the president at the Office of American Innovation. And with Rollins at the center of things, Right on Crime wonks like Marc Levin and Derek Cohen were the effort’s de facto policy experts.

It was in these meetings that Doug and others concocted a four-state experiment to complement the federal legislation they planned to push (it has since expanded to seven states). Doug sat on the advisory council and, along with the Charles Koch Foundation, provided most of the funding for the initiative, called Safe Streets & Second Chances. The idea was to pair prisoners in Texas and elsewhere with counselors who’d offer guidance and support from lockup to life outside, like a larger-scale cousin of Tina Naidoo’s Texas Offender Reentry Initiative. All the while, researchers would monitor the travails of the newly released and catalog the vicissitudes tripping up their reintegration. Over the course of five years, the team, led by a Florida State professor named Carrie Pettus-Davis, would figure out what helped and what didn’t. If the approach reduced recidivism, Right on Crime would help push the program to other states with the argument that lending a hand to former prisoners was cheaper than locking them up again.

On the legislative front, Trump finally spoke out in support for the first time that May, highlighting reforms that would sound familiar to Texas legislators. In fact, the president’s remarks echoed the contents of a bill filed weeks before by Collins. The First Step Act passed in the House with bipartisan support. But the bill was slow-moving in the Senate. Cruz had his concerns. The usual tough-on-crime throwbacks like Tom Cotton of Arkansas and John Kennedy of Louisiana claimed the legislation was tantamount to flinging open the prison gates and releasing rapists and murderers. And Judiciary Committee Chair Chuck Grassley and Sen. Dick Durbin wouldn’t support anything that didn’t contain sentencing reforms. Progress in Grassley’s committee ground to a halt in June, once Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy announced his retirement. Things didn’t pick up again until October, after the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh, practically on the eve of the midterm elections. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell all but rejected the idea that there was time to advance the legislation in the lame-duck weeks after the election and before Christmas break. After that, nobody could say what would happen with the Democrats in control of the House and McConnell running the Senate. The resulting gridlock could spill over.

And so Doug and his fellow reformers orchestrated a behind-the-scenes pressure campaign in what can only be described as an all-out race to beat Christmas. Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin, Sen. Rand Paul, and Paul’s wife, Kelley, a former political consultant, started working on McConnell. Doug says Trump even phoned the majority leader, asking for a floor vote.

The Texas delegation was largely left to Doug. Cornyn was quietly supportive but hoping to get the National Sheriffs’ Association’s blessing before he spoke out. Cruz was still a no. Doug was in D.C. at the moment, so he gathered Cruz, Sen. Mike Lee, and a Right on Crime policy analyst in a subterranean room beneath the Senate to hash out what it would take to get Cruz to say “aye.” The senator said his concerns hadn’t changed since 2015. He worried about the retroactive provision to reduce sentencing disparities between crack and cocaine and fretted about giving liberal judges too much discretion to release violent felons.

Now came the familiar “whittling down” Doug knew all too well from his days in the Legislature: how to make Cruz happy without running off Democrats like senators Dick Durbin and Cory Booker. Doug and his allies had a spreadsheet populated with members of Congress and anyone they might listen to or owe a favor. The Coalition for Public Safety inundated the country with print and digital support for the legislation. But time was running out. With Cornyn still in the undecided column, representatives from Koch-funded organizations like the Cato Institute, the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, and the Heritage Foundation were leaning on Doug to take more extreme measures.

Doug says, “All these different advocates were saying, ‘You need to blast him. You need to come down hard. You need to put the pressure on him in Texas.’ And I said, ‘I’m not going to do that. We’re gonna win him, I promise you.’ ” Years before, blasting his nondisclosure bill’s Senate author hadn’t been what kept him onboard. It was a light touch (and a gentle nudge from Rick Perry). Doug’s patience paid off. “A few days later, I talk to Cornyn on the phone,” Doug says. “He says, ‘I give up, Doug. We’re not gonna get [the National Sheriffs’ Association].’ ”

Cornyn was in and Cruz was soon mollified. The legislation would contain Texas-style reentry provisions as well as some modest sentencing reforms. The final version was agreed to on December 12. But under the byzantine rules of Congress, that wouldn’t leave enough time to reintroduce and amend the bill by Christmas. To beat the deadline, the authors and leadership gutted the Save Our Seas Act, which had already cleared the Senate and been returned by the House. They replaced language authorizing funds for the cleanup of “severe marine-debris events” with the contents of the renamed First Step Act, jettisoning the tortured acronym. The Senate passed the bill a little after 8 pm on December 18, with an overwhelmingly bipartisan majority and just days to go. It passed the House a day and a half later.

That evening, Doug was in La Jolla, California, at the family compound with his fiancée, Jacki Pick, host of The Jacki Daily Show, on Glenn Beck’s Blaze Media network. When he got word, he filled two Champagne flutes with a 2006 Dom Pérignon.

On December 21 at around lunchtime, D.C. was under a flood watch, and the skies were leaden. In less than 12 hours, the government would shut down for more than a month, the longest in history, because of a border wall. Bipartisan relations in Washington were as frosty as they’d ever been, and winter was still on the way.

But in the Oval Office, for at least a little while, the federal government still appeared functional. Trump was signing into law the most sweeping criminal justice reforms to the federal system since Bill Clinton was in office. Doug doesn’t show up in most of the official photos of the crush jockeying for real estate around Trump during the Oval Office signing ceremony. He’s a few bodies to Kushner’s right and a couple of heads behind Vice President Mike Pence, his face mostly obscured by the president of the International Association of Chiefs of Police. But the guy who only a few years before had been hustling a nondisclosure bill for low-level misdemeanors was at the center of Trump’s signature legislative achievement, one he’d still be touting more than a year later in Super Bowl ad buys.

Doug conceded that the law was a first step; more would have to follow. But the legislation would help people, as that nondisclosure bill had. Nearly 1,700 inmates would see their sentences reduced due to the law’s retroactive application of the Fair Sentencing Act, scaling back the disparity between crack and cocaine sentences. More than 3,000 federal Bureau of Prison inmates would be released on good-conduct time. Ninety-one percent of them, by the way, were black. As with the race-blind messaging behind Texas reforms, one could argue that the First Step Act disproportionately helped blacks and that blacks had been, and likely would continue to be, disproportionately impacted by the justice system.

But the ink was hardly dry on Trump’s signature before his own Department of Justice began arguing in court against the release of prisoners under the law. And the offense types excluded from early release were sweeping, such as most immigration offenses, alleged gang affiliation, and a widely drawn definition of “violent” that could include many assault categories and possession of a firearm. The scope was limited. It’s also fair to say this was all a drop in the bucket. The law allocates $95 million annually to state and federal substance abuse, reentry, education, and vocation programs, patterned after what Texas had done. That comes to about $14 per inmate per year.

Perhaps that’s what you get when you ask, as Trump did, for “criminal justice reform, Texas style.” The Lone Star State never claimed to end mass incarceration. It lopped off some low-hanging fruit—mainly individuals facing, or locked up for, drug charges who could be diverted or released without any resulting headaches—and merely flattened the growth curve. Texas still has the seventh-highest rate of incarceration and the largest prison population in the country.

Texas and the First Step Act measured how far Republicans were willing to go. The reforms were always going to be modest, narrowly tailored, largely blind to the arc of a life before prison. They don’t see the poor, unintegrated communities with their unequal schools and limited access to healthcare and living-wage jobs—the kind of place where Dondi Wafford grew up. In fact, the repeal of Obamacare and opposition to living-wage laws remain a central tenet of the Koch conservative belief system. Doug once famously threatened to close the “Dallas piggy bank” unless Republicans followed through with the repeal of the Affordable Care Act.

Nearly all prisoners will be released back into the communities they came from. How they’ll fare is primarily a function of their circumstances before they went in. If not for a wealthy white man whose eased passage through the criminal justice system had been its own revelation, that’s where Dondi Wafford might very well still be struggling. But there isn’t a Doug for every Dondi.

Write to [email protected].