When the last elementary school fundraiser for her twins rolled around, Amy Herrig made sure she had the winning bid at the silent auction for the most coveted prize: a dinner prepared at home by Mi Cocina founder Mico Rodriguez. Amy and her second husband, Dan, had just moved to Highland Park from Devonshire that November, buying a $2 million Spanish Colonial from an anesthesiologist and his wife, who were downsizing from the 6,000-square-foot house on a corner lot. Now it was May. The pool and landscaping had been finished, and she was ready to show it all off. The dinner was the perfect excuse.

The day of the party was balmy, and it was easy to picture her well-coiffed and manicured guests sipping margaritas and munching on chicken taquitos as they mingled around the lit courtyard. But Amy was still anxious. The guest list included her friends as well as some society types she wouldn’t normally have the nerve to ask over. She didn’t have a barre-toned body like theirs, she didn’t shop at Elements like they did, and she didn’t have a $300 balayage dye job like they did. More Melissa McCarthy than Rose Byrne, she could probably be dropped into the Alaskan tundra and find her way out. A Park Cities cocktail party was another matter entirely.

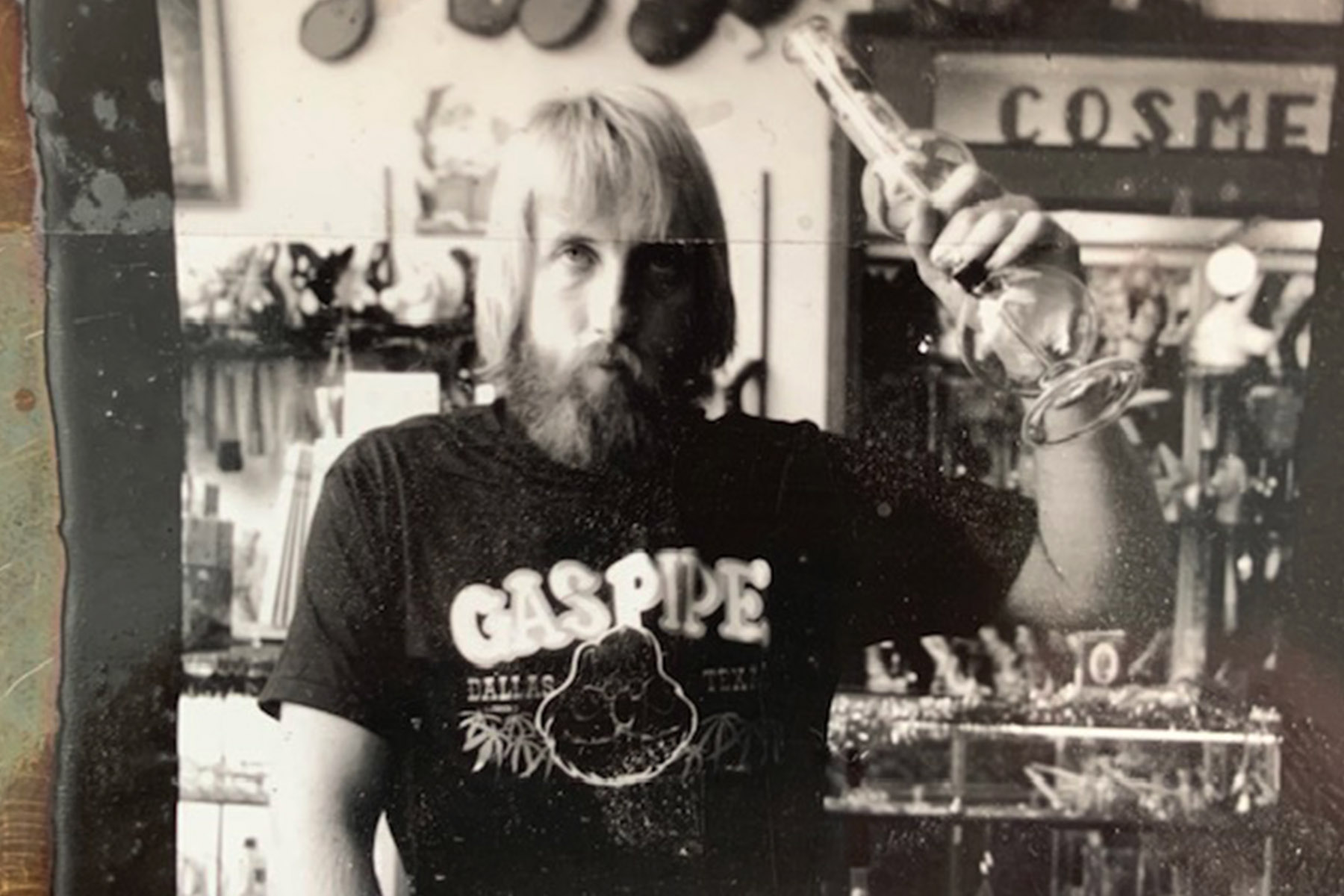

She never thought she’d live in a house like this. Not that she’d ever wanted for anything. She just grew up in a different world. Her parents were pot-smoking, peace-loving, nudity-positive vegetarians who had found a way to turn their hippie ethos into a capitalist dream. Her father, who had been raised in a military family, had volunteered for the Air Force during the Vietnam War. After several tours of duty, he returned to Texas in 1969, decorated but disillusioned. He found kindred spirits in Dallas, where he often hung out with protesters in Lee Park. He started peddling t-shirts and eventually saved enough to open a small store on Maple Avenue where he sold Easy Rider posters, rolling papers, and scented candles. He named it the Gas Pipe, partly for the exposed pipes in the ceiling and partly for his initials: Gerald “Jerry” Allan Shults.

Amy lived in Dallas as a child, playing in her father’s multiplying storefronts and the Hair Revue salon he opened on Oak Lawn. But in the early 1980s, when anti-paraphernalia laws went into effect and Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign kicked into hyperdrive, police routinely raided Jerry’s stores, guns drawn, looking for contraband. Because of the bad press, the Montessori school that Amy attended asked her parents to withdraw from its board. Jerry decided to move the family to Lake Whitney, out of the fray, where they already had a vacation home. So Amy grew up a quasi-country girl, a smart, loudmouthed cheerleader with a penchant for bad boys.

An only child, she was well loved and well provided for, but her mother and father had their own baggage, and they divorced her senior year. It’s hard to rebel when your parents own a head shop, but Amy took the opportunity to progress from pot to LSD to cocaine to heroin.

That’s why this party meant so much. While the other moms in her children’s Highland Park elementary school had gone to SMU or UT, joining sororities and dating guys whose family names graced campus buildings, Amy had struggled to free herself from an abusive boyfriend, get clean, go to executive secretarial school, and wait tables at Macaroni Grill. It didn’t matter that she eventually got her degree and was now a successful businesswoman, running a multimillion-dollar retail operation with her father. It didn’t matter that they had just doubled their fishing lodge business, adding locations in Canada, Chile, and the Bahamas. It didn’t matter that, in addition to the Highland Park home purchased near her ex-husband, she and Dan had also bought vacation homes in Oregon and Baja California Sur, on the beach. It didn’t matter that they had just built a private house at the lodge her father owned in Alaska and bought four new airplanes so they could start a charter air service there. She still felt like an outsider.

Looking back now, she remembers people telling her after the party that they had a fabulous time, but she can’t recall whether she enjoyed herself. The real reason the event has stayed seared in her memory is because of what happened less than two weeks later, on June 4, 2014. This was simply the peak of hubris before the fall.

Amy left the twins with her godmother on June 3 and flew to Alaska with her husband and her father to open the fishing lodge for the season. Early on, Jerry’s Gas Pipe customers included Texans and Okies who were doing seasonal work on the Alaska pipeline, and they often told him how amazing the fishing was there. Jerry had been tying flies since he was 13. He finally went to see it for himself in 1986, and he fell in love with the place. In the early 1990s, he bought Rapids Camp Lodge on the edge of Katmai National Park and Preserve. It had felt karmic, the fact that it was a former Air Force retreat for the nearby military base, but there really wasn’t much more than a shack sitting on 60 acres when he bought it.

Over the years, the Gas Pipe business had been good, what with the unexpected popularity of Gonesh incense and Michael Jackson earrings. So Jerry had been able to turn the property into a rustic retreat with a new lodge, nine guides, four pilots, two chefs, and a fleet of custom boats and amphibious planes.

It’s where Amy met Dan, back in 2008, after separating from her husband and filing for divorce. Dan had been hired as the new lodge manager, and Amy had started helping out her father with the lodge business. She gave Dan a kiss on the cheek that summer, after he’d helped her catch the largest salmon of her life, and she found herself daydreaming about his hands as she watched him clean it.

Six years and a marriage later, on the morning of June 4, Amy and Dan were drinking tea and checking email when Amy got a note from the office manager to give her a call. The office manager told her that one of the new floatplanes had been seized by federal authorities in Anchorage. Amy’s first thought was that maybe the previous owner had done something sketchy and there was a problem with the title.

Then she got a call from a pilot who said they had seized a second plane. That was followed by a call from the manager of the historic Ridglea Theater in Fort Worth, which her father had bought and saved from demolition. He said DEA agents had the building surrounded and were raiding the attached Gas Pipe store.

It has to be a mix-up, Amy thought as she called her attorney, starting to panic. He called the U.S. Attorney’s Office, which told him the DEA had made several controlled buys of illegal substances from multiple Gas Pipe locations, and they were in the process of seizing all of Amy’s and Jerry’s personal and corporate assets.

When Amy heard this, she was stunned. She had no idea what they were talking about. That’s when she got a call from her neighbor. “Is everything OK?” he asked, sounding concerned. He had just driven by her Highland Park house, and he said it was cordoned off by yellow tape and teeming with officers and armored vehicles.

“They’re at my house!” she screamed at her father.

She would find out later that at the time of the raid, her 9-year-old son was at lacrosse camp, but her daughter was at home with her godmother. As DEA agents tugged on a bookshelf to see if there was a secret cubbyhole behind it, they asked the little girl to show them the house’s hidden rooms. She dutifully took them to the guest room closet, where she pointed to the opening that led to the crawl space under the house. But the agents found nothing hidden there, or anywhere. The drugs had been in plain sight the whole time.

Head shops emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s, offering oddities and accoutrements related to hippie counterculture and the mind-expanding drug scene. Along with incense sticks and beaded doorway curtains, they often sold paraphernalia for, mostly, marijuana use: pipes, bongs, roach clips, vaporizers, rolling papers, scales, lighters. In the 1980s, federal and state laws attempted to limit the sale of drug paraphernalia, and what Jerry refers to as the Pipe Wars began.

Today, at 73, Jerry looks more like Andy Griffith in his Matlock years than Cheech or Chong. He’s tall, with short gray hair, bright blue eyes, and the same easy way with hunting dogs and small children. So when he describes the police raids from decades ago, it sounds a little like Sheriff Andy Taylor trying to reason with Deputy Barney Fife.

When the cops would come in and seize all of the pipes, Jerry would bemusedly counter, “What about meerschaum pipes?” Since the carved German pipes were legal in tobacco shops, the cops would acquiesce. The opposing sides would laboriously go through the same confused routine with wooden pipes, and metal pipes, and pipes made from lamp parts. Sometimes they’d be confiscated and destroyed; sometimes they’d be returned with an apology. Eventually, the parties reached an understanding. The pipes were only illegal if they were sold and used for an illegal purpose. Jerry started labeling them “for tobacco use only,” and the issue seemed to die.

By the early aughts, the social stigma of marijuana had all but disappeared, and Jerry was a self-made multimillionaire with six Gas Pipe stores in Texas and New Mexico; his own purchasing and distribution company, Amy Lynn Inc. (named for his daughter); and the Rapids Camp Lodge.

When they arrived at the jail, Amy and Jerry were separated. Amy was given yellow prison scrubs and oversize white underpants. Bras and socks had to be purchased from the commissary.

In 2005, about a year after her twins were born, Amy went to work for her dad. Jerry was hoping to breathe some new life into Amy Lynn Inc., and Amy had fresh ideas about updating the payroll and point-of-sale systems. She started acquiring new properties for Gas Pipe locations, and she helped scout out a lodge in Patagonia to add to their travel portfolio. Business was good.

Then, seemingly out of nowhere, a new product known as K2 emerged on the market. Also called spice or herbal incense, it was a synthetic cannabinoid. It had been developed by a Clemson professor named John W. Huffman in an attempt to create a medicinal drug with the pain-relieving and health benefits of THC but without the high. In fact, Huffman created the opposite: a legal synthetic form of THC with an even greater psychoactive potential than marijuana. He named the compound JWH-018, using his initials, and in 2008 he published a paper outlining its makeup. From there, open-source market forces took over.

By 2011, the federal government had caught on and made JWH-018 a controlled substance. But a game of whack-a-mole ensued. Minor changes would be made to the chemical compound, and a new synthetic cannabinoid would be released on the market. For the most part, people in the industry—head shops, gas stations, mini marts—considered these new compounds to be legal until they were specifically named and outlawed by the feds.

The drugs came in small, brightly colored Mylar packages that resembled condom wrappers, if condom wrappers were resealable for a subsequent use, with names like No More Mr. Nice Guy, Assassin Revolution, and Alien Loose Leaf. A popular one, called WTF, featured a cartoon image of Fidel Castro on a toilet. As in the days of the Pipe Wars, in an effort to avoid legal issues, the Gas Pipe products contained disclaimers like “lab certified legal,” “not for human consumption,” “keep out of reach of children,” and “intended for adult use only.” Some went so far as to say “100% synthetic cannabinoid free.”

The product contained in the packages was made from dried plant material from things like damiana, a native Texas shrub, or althaea, known as the marshmallow plant, which were treated with the chemical compound of choice. It looked like dried oregano, hence the nickname “spice,” but it couldn’t be advertised as intended for ingestion without running afoul of the FDA, so sellers referred to it as incense or potpourri. But nothing about the packaging or the product suggested that it would make a room smell better. Everyone knew you smoked it to get high.

Jerry wasn’t interested in herbal incense at first. He was an old-school, homegrown-pot kind of guy. Plus, in August 2010, the city of Dallas banned several specific herbal incense compounds after some teenagers in Denton smoked the stuff and ended up in the hospital. But in the ensuing months, Jerry started getting more and more calls from customers requesting it. And an aggressive statewide distributor, Lawrence Shahwan, convinced him that it was all the low-quality product on the market that was making people sick. His stuff, he said, was top-notch. And it wasn’t on the banned list.

Over the next four years, the Gas Pipe would sell more than a million packages of herbal incense and generate more than $40 million in revenue. And Amy found herself addicted to a new kind of green.

Nearly a year after the initial raid, on May 13, 2015, Amy took the kids to Chick-fil-A for breakfast. She gave them a big kiss goodbye before dropping them off at school and then picking up her dad. The plan was to surrender themselves at the U.S. Marshals Service in downtown Dallas. She had tried it once before, at the urging of her attorney, hoping to avoid having the agents show up at her home in front of her kids, but after talking with four people at the marshals office, she was told there were no warrants out for their arrest. All they could do was go home.

She got tired of waiting for the knock on the door, so here they were a week later, trying it again. It was a Wednesday, and the kids were scheduled to stay at their dad’s through the weekend. She figured she’d just have to wait in a holding cell in the federal building for a couple of hours while her paperwork was processed, and in the morning she’d be able to go before a judge and enter her not guilty plea. No matter what, she’d be home in plenty of time to make her daughter’s piano recital on Sunday.

This time, the federal agents had the warrants. But it was late in the afternoon before they got around to processing Amy and her father. They were told they could go home and come back in the morning, or stay and spend the night. Amy was worried the officers might still show up at her house if they went home, so she opted to stay. She’d been briefly jailed a couple of times in her youth for writing bad checks, and it hadn’t been a big deal. But after she and her father finished the paperwork, they were told they would be bused an hour away to the Kaufman County Jail for the night. That hadn’t been part of the plan.

I should have worn socks, Amy thought, staring at her sandaled feet as officers shackled her wrists and ankles. The metal cuffs dug into her skin as she shuffled onto a bus with prisoners in yellow uniforms who had come to Dallas that day for sentencing. When they arrived at the jail, Amy and Jerry were separated. After a strip search, Amy was given yellow prison scrubs and oversize white underpants. She was told bras and socks had to be purchased from the commissary.

The guards were kind, and Amy had her own cell. She was given a dingy mattress, a scratchy blanket, and a plastic bag with a comb, a bottle of shampoo, a bar of soap, a toothbrush and toothpaste, and a roll of toilet paper. The fluorescent lights remained on all night, but that wasn’t what kept Amy awake. She didn’t yet know what she was being charged with, but she knew that the smallest of the threatened offenses carried a five-year maximum sentence.

The next morning, Amy and her father were taken back to Dallas for the arraignment, and they finally learned what they were facing. The federal grand jury had indicted 32 defendants, including Amy, Jerry, Gas Pipe Inc., Amy Lynn Inc., Rapids Camp Lodge Inc., and most of the Gas Pipe’s regional and store managers. The charges included conspiring to manufacture and distribute controlled synthetic cannabinoids, importing controlled substance analogues from Denmark and China, money laundering, and conspiring to defraud the U.S. government by introducing a misbranded drug into interstate commerce. When it was all added up, Amy and Jerry were each effectively facing a life sentence.

Worse than her failure to wear socks was Amy’s failure to realize that her attorney was out of town for the weekend, so the detention hearing would have to be postponed until Monday. She and her father would have to spend four more nights in the Kaufman County Jail.

Amy found herself in a new cell with five roommates. The young women were all either awaiting sentencing or they had been sentenced but there was no room for them in the federal prison. Some had been there for months, one closer to a year.

Because it was intended only as a holding jail, there was no access to therapy or rehabilitation programs. There was no exercise yard, work programs, or computer access. Most of the inmates didn’t even realize that they could make phone calls if they had the money to set up an account, and visitation was limited to one 15-minute encounter per week. These women weren’t violent offenders, but they were more confined than those who had committed much worse crimes.

Unlike Amy, who had potentially endangered hundreds of thousands of lives and was essentially charged with being a drug kingpin, her cellmates were mostly users and low-level dealers, who might have been customers at the Gas Pipe when their drug of choice ran out and they could only afford a cheap bag of WTF. Or maybe they had been busted for buying an equivalent product on the street. Regardless, they didn’t have the resources to get clean and go to college and get a job, let alone continue to work for the family business to pay for a lawyer to challenge their detention. The best they could hope for was to reach a plea deal, save up to purchase a coffeepot in the commissary to cook their own noodles, and get doped up on the antidepressants their jailers were more than happy to provide.

As for Amy, she would end up missing her daughter’s recital. But she’d be back in her own bed, wearing her own underwear, in just a couple of days.

Amy was released to spend the next 17 months under house arrest, wearing maxi dresses to hide the unwieldy ankle monitor she nicknamed Bertha. She had to get permission from her pretrial officer to go to the grocery store or to church, but he was relatively lenient and would let her swim in the backyard pool even though it was far enough from the house that it would trigger the monitor. As long as GPS confirmed she was on her property, he was cool with it.

She was also allowed to go to work to keep the businesses running, although she was a little miffed that the judge excluded travel to Alaska. She thought it was a strange irony, the court’s willingness to presume her innocence and the legality of her endeavors while seizing every asset, making it nearly impossible to keep the company afloat and employ a legal team to defend herself. Even before any criminal charges were filed, the feds emptied all of her and her father’s bank accounts. They took all of the computers and cash registers, all of the QuickBooks files and records. Since Jerry owned most of the stores outright, the government put liens on all of the real estate. That meant they couldn’t get a loan or sell off property to raise funds. When they were charged with money laundering, their banks dropped all of their accounts.

All they could do was open the doors to customers and start by taking cash-only transactions, keeping records with pen and paper, just like Jerry did at the first Gas Pipe store. A friend of a friend with a bank agreed to take them on. But in the beginning, they put a lot of debt on credit cards. They had about $250,000 in outstanding bills at the time of the raid, plus payroll and a six-figure sales tax bill due. That’s part of what they couldn’t wrap their heads around: they’d been keeping a detailed inventory and paying taxes on the proceeds for years.

Plus, there was that time in 2014 when the head of the Organized Crime Division in Austin approached the managers of the Gas Pipe stores there and asked for their help to figure out who was selling a tainted product called The Walking Dead, which was making people sick. No seizures or arrests were made in the store then, even as samples of the Gas Pipe’s herbal “potpourri” smoldered in incense holders atop glass display cases of the stuff.

Another time, they had a robbery in a store, and the cops ended up catching the guy. He was ordered, among other things, to pay restitution for the herbal incense that he stole.

And that August, cops seized 2,997 packets of spice from the Gas Pipe store in Arlington. They opened three or four packets to test them, and then, when it turned out it wasn’t the same stuff that had been sending people to the hospital, they returned the rest with a check for $116.95 to cover the packets they destroyed during testing. It was all relatively civilized and professional, just like in the days of the Pipe Wars.

They purchased restaurant bus tubs and a kitchen mixer to mix the chemicals with the plant material, and they set it all up in a back room of a warehouse on Maple Avenue.

If they ever crossed a line, Amy and Jerry figured they’d hear about it. And then they’d correct it, just like they had every time they found out a new compound had been put on the federal controlled substance list. They’d already destroyed thousands of dollars in inventory. What kind of drug dealers would do that?

But in retrospect, it is pretty clear they were turning a blind eye to the state of the larger marketplace. Dallas Fire-Rescue was dealing with hundreds of calls for K2 overdoses. People under the influence were described in news reports not as giggling stoners jonesing for Little Caesars, but as mumbling zombies stripping naked and walking in front of DART trains; lurching through police car windows at officers in a paranoid, hallucinatory frenzy; or simply seizing and vomiting on the ground.

A Parkland ER doctor testified at trial, “It was really like a zombie apocalypse.” She stated that people under the influence would often exhibit “superhuman strength,” and it might take 10 to 12 officers to restrain a patient. Even after patients were placed in four-point restraints on a bed, they would sometimes stand up with the stretcher still attached, “moving around the emergency department like a turtle.”

The street stuff was cheap, going for as little as $2 per packet, so it was becoming a drug of choice for teenagers and the homeless. And because it was generally marketed as not for human consumption, even the stuff sold in stores was unregulated. By 2014, when the Gas Pipe was raided, more than 175 forms of synthetic cannabinoids were in circulation nationally. There was no way for consumers to know what chemical compound was in any given batch, or how much, or if it had been laced with formaldehyde, rat poison, butane, heavy metals, or even salmonella. In Dallas, 100 people overdosed on K2 or herbal incense in May 2014 alone.

What Amy and Jerry didn’t know was that from November 2013 through May 2014, undercover officers had made purchases of herbal incense at each of the Gas Pipe’s 13 locations. When the officers tested the products, they identified traces of two specific controlled substances, as well as a number of substances they claimed were analogues—chemical compounds that are substantially similar to a controlled substance and therefore banned under the Controlled Substance Analogue Enforcement Act of 1986.

While Amy and Jerry thought they were staying ahead of the law by avoiding specifically banned substances, they didn’t realize that in the wake of the growing public health crisis, the DEA had been enforcing the decades-old law. In fact, in December 2012, the DEA had unleashed its largest synthetic drug takedown on a global scale, ultimately making hundreds of arrests across 35 states, 49 cities, and five countries, seizing more than $51 million in cash and assets and more than 9,000 kilos of designer drugs, including “bath salts” (synthetic cathinones) and synthetic cannabinoids.

In a press release issued at the time, the DEA touted the Analogue Act to officers as a key tool in prosecuting all of the newly emerging drugs. And the agency issued an explicit warning.

“The criminals behind the importation, distribution, and selling of these drugs have scant regard for human life in their reckless pursuit of illicit profits,” said Traci Lembke, deputy assistant director of investigative programs for Homeland Security. “For criminal groups seeking to profit through the sale of illegal narcotics, the message is clear: we know how you operate; we know where you hide; and we will not stop until we bring you to justice.”

I meet Amy for the first time in October, on the patio of a coffee shop near her office on Maple Avenue, to talk about her memoir, No More Dodging Bullets. She started writing it during her 17 months under house arrest, but she hasn’t finished it yet. She’s waiting to write the epilogue until after she is sentenced, and the hearing is scheduled for the following week.

After reading a draft of her book, and then some of the news reports and trial transcripts that she chose not to include, I don’t want to like her. At best, she took advantage of a legal loophole to sell a dangerous product to the public, like tobacco and vapes, but without any FDA oversight. At worst, she knowingly manufactured and distributed a potent and addictive controlled substance that can cause heart attacks, seizures, and kidney damage.

But Amy is smart and articulate and self-deprecating, and it is hard not to be charmed. Despite the occasional legal argument, she doesn’t make excuses for what happened. And she’s strangely at peace for someone who has spent the better part of five years facing a life sentence. She now knows it won’t be that, but it could still be enough that she won’t see her kids off to college.

“We should have walked away a lot sooner,” she says. “I mean, it wasn’t a positive thing to bring into the community. And I’ll readily admit that. I think it’s really easy for human beings in general to get wrapped up in power and money even if they don’t mean to. And I, at 39 years old, alongside my father, was running this huge business that was very, very, very successful.”

The case was initially supposed to go to trial in May 2016, but it kept getting postponed. First, it was because the John Wiley Price trial was in front of the same judge, and that case kept dragging on. Then Amy was diagnosed with breast cancer in January 2017, and the judge delayed the trial to allow her to undergo treatment. The case didn’t go before a jury until October 2018, and it would take another year for the sentencing.

It was during the trial that Amy found out that their main supplier, Lawrence Shahwan, had been behind all of the “customer” calls to the Gas Pipe that convinced Jerry to carry herbal incense in the first place. But Amy acknowledges that it didn’t take her long to get addicted to the money it brought in. And when Shahwan went AWOL on their $4 million contract in 2013, and one of his employees simply dropped off what was left of the raw chemicals in lieu of the finished product, she didn’t think twice about starting to manufacture the product herself.

“We had in all honesty talked about manufacturing it ourselves because of quality control,” she says. “You get this ready-made product—you get 30,000 packages of it—you can’t test every single package. You take a representative sample, and that’s the best you can do. If we were making it ourselves, we would know exactly what was going in it. The government claimed, ‘Oh, they did it all to make much more money.’ Well, the profit margin on this stuff, even ready-made, was ridiculous. I mean, it wasn’t really to make more money. It was really just a thing that fell in our lap.”

They purchased restaurant bus tubs and a kitchen mixer to mix the chemicals with the plant material, and they set it all up in a back room of a warehouse on Maple Avenue. The front of the building is now the storefront for Deneki Outdoors, Amy and Jerry’s fly-fishing outfitters company. It’s filled with travel brochures, mounted water buffalo and warthog heads, and model airplanes, but it used to be where Amy’s aunt and uncle had a custom framing business. Amy says they closed the framing business in December 2013, right around the time she started manufacturing. She says that’s why the commercial metal shades were always rolled down across the front, not because they were trying to hide the manufacturing operation, as the government argued at trial.

But Amy admits it wasn’t pretty. “It was a homemade science experiment gone wrong,” she says. “I would not call this a lab at all. They did a very good job in the trial of making it look very disgusting and nasty. I don’t really recall it looking that disgusting and nasty when we were doing it, but honestly—and I’m not trying to be dismissive of my role—I didn’t spend a lot of time back there, anyway.”

At trial, Jerry’s attorney, George Milner, used a cake baking analogy to explain why trace amounts of controlled substances were found in the product. As chemical compounds were outlawed and taken out of production, the equipment wasn’t getting cleaned properly, so residue remained. That’s what the government was finding in their tests, Milner argued. He said it was like trying to mix vanilla icing in the same KitchenAid where you previously mixed chocolate cake. If the chocolate batter wasn’t completely cleaned out of the mixer first, then the vanilla icing would be contaminated with chocolate. He managed to convince the jury that the contamination wasn’t intentional. But it certainly didn’t make for a quality cake.

Amy and Jerry’s even bigger problem was the analogues—the vanilla icing that they were actually mixing. After their arrest, the Supreme Court had issued a decision in McFadden v. United States, which was intended to clarify the knowledge prong of the Analogue Act. The court determined that defendants could be found liable if they either knew that the substance at issue was controlled—it was listed on federal drug schedules or had previously been treated as such under the Analogue Act—or they knew that the substance was substantially similar to a controlled substance.

But what does “substantially similar” mean? An average customer could probably determine if the high they got from an illegal form of K2 on the street was pretty close to the high they got from a package of WTF from the Gas Pipe. But as far as the legal defense team was concerned, if Amy and Jerry didn’t know for a fact that the chemical makeup of WTF was virtually identical to that of the banned K2, then they shouldn’t be found guilty. And how could they know that for a fact if they weren’t chemists?

Milner knew things would end up getting technical at trial, with a half-dozen experts arguing about bonds and molecules, bandying about nonsensical strings of letters and numbers and boring the jury to death. So he needed to simplify things. His first opportunity came about thanks to the lead prosecutor, during jury selection.

Milner tells me that the lead prosecutor asked one of the potential jurors something along the lines of, “If you’ve got a red Ford F-150 pickup that’s a 2016 model and you’ve got a red Ford F-150 pickup that’s a 2017 model parked next to each other, would you say that those were substantially similar?” The juror responded, “Yeah, I guess I would.” Milner realized that one of the members of the jury pool was Jerry Reynolds, host of the nationally syndicated CarPro Show on WBAP. He decided to have some fun with the guy, so he asked Reynolds the same question. Reynolds responded that there could be a myriad reasons why the trucks would be totally different and sell for very different prices. One might be damaged, or have more mileage, or have newer and more advanced parts.

There was also a chemistry teacher in the potential jury pool. Milner turned to her and asked, “As I’m sitting here talking to you, am I expelling CO2?” “Yes,” she responded. “What is that?” he asked. “It’s carbon dioxide,” she replied. “What if I just cannot deal with the stress of being a lawyer anymore, and I go to my house tonight and close my garage with my car in there, and I turn on my car and close the doors? Is that CO, or carbon monoxide, as opposed to CO2? Is it true that I’ll probably be dead in about 30 minutes?” he asked. “Yeah, that’s a good estimate,” she said. “So we change one molecule that my body is producing, and it’s a gas that’ll kill me. But it’s only one molecule difference,” he concluded.

Neither of those potential jurors actually made it onto the jury, but Milner had made his point. When the experts at trial couldn’t come to an agreement as to whether or not the various chemical compounds sold by the Gas Pipe were substantially similar to banned ones, the jury decided that they couldn’t, either. After two days of deliberation that stretched over a weekend, they found Amy and Jerry not guilty on all counts save for one: felony misbranding with intent to defraud the FDA.

That meant the forfeiture claim based on the illegal drugs was now moot, but the government simply reopened the initial civil case. After Amy’s bout with breast cancer and a stroke Jerry had suffered months before the trial, they didn’t have much fight left in them. So they decided to settle the civil suit for just shy of $13 million. They sold the two Gas Pipe stores in Austin to help raise the funds. Meanwhile, one of the million-dollar airplanes that the government had seized and moved to a hangar in Houston had been damaged and lost in Hurricane Harvey. Amy and Jerry were upset that they didn’t get a credit for that.

But they had also gone from a possible life sentence to a maximum of five years. That’s what Amy was now waiting for. To find out how much of that time Judge Barbara Lynn would order her to serve.

Behind the deneki outdoors showroom and down a long hallway, there’s a large back room that looks like a cross between a halfway house and a fishing lodge. It tends to be populated at any given time by a half-dozen friendly hunting dogs and pit bulls, which belong to Amy, Jerry, and various employees. There’s a lounge area with an old couch and a TV, and a kitchen with a large communal table. There are three refrigerators and shelves stocked with Costco-size jars of peanut butter, commercial soup pots, and aluminum baking pans. When I visit, there are a couple of men standing at the table, making dozens of sandwiches in an efficient rhythm of bologna slices and cheese. Just behind this room is the warehouse, where the herbal incense manufacturing operation once took place. Now it serves as the headquarters for Amy’s new nonprofit, Hopeful Tuesdays.

In 2017, before the trial, Amy had been cleared to go to Philadelphia with her husband for a business trip. It was right after she had been diagnosed with breast cancer. Amy had never been one to give money to the homeless, but as she and her husband were walking to dinner one night, they passed a man sitting on the sidewalk. Amy decided to stop and talk with him for a minute, and she brought him back dinner from the restaurant. When she found out he had a job interview at Starbucks, she went out and bought him pants and shoes and put him up in the hotel for a couple of nights so he could shower and get cleaned up.

After she came back to Dallas, the company held its annual darts tournament at a bar down the street from the office. She looked out the window and saw a man sleeping in the stairwell of the building across the street.

“I looked around, and we were surrounded by food and gluttony—everything we need,” Amy says. She brought the man a cheeseburger and told him there was a shower in the office if he wanted to come over the next day and use it. “You would’ve thought I’d told him he’d won the lottery. They can get food a lot of places, but getting a shower is hard. That was a Monday. I said, ‘Why don’t you come back tomorrow and bring some of your friends?’ So he came and brought a couple people, and we just sort of decided that every Tuesday we would have whoever wanted to come have lunch. And they could take a shower.”

What started with a handful of people has turned into a near daily operation. Before the coronavirus pandemic, they would invite people into the office for food, fellowship, and showers. Now, Amy and her volunteers distribute sandwiches in the streets to 30 or 40 people every Tuesday through Friday.

“I’m not saying all this to brag about what we did,” Amy says. “But it was kind of my first step into looking at people who maybe have gone through some hard times differently. Yes, most of them have made bad choices and that’s kind of where they are. But I can relate to that now. I can relate to making a bad choice and then almost losing everything over it.”

The sentencing hearing ended up stretching for two days across two months. It included the testimony of emergency doctors, pharmacologists, and toxicologists. They explained that there are currently more than a thousand different synthetic cannabinoids available in licit and illicit marketplaces around the world, most of which are far more powerful and far more toxic than marijuana. They all contain minute differences, but they have become more and more similar in terms of the consistency of their adverse effects, which include seizures, cardiac arrest, and death.

Even though the jury had found Amy and Jerry not guilty on the charges related to the sale of illegal drugs, there was still more testimony about molecular compounds and atomic structures, the endless litany of letters and numerals that had left the jury unable to find a substantial similarity in the compounds. But the federal prosecutor, Chad Meacham, argued that Judge Lynn should find them to be the same. Under the law, she was permitted to take acquitted conduct into account for sentencing, and so Meacham believed she should. He asked that she apply the maximum possible sentence of 60 months to the crime for which they were convicted, mislabeling of a product intended for human consumption, based on the clear dangers that the product presented.

He noted that the defendants were well aware that Oscar Maldonado, a 17-year-old Plano West Senior High School student, died in October 2013 after smoking spice at a friend’s house in Garland. No one knows if the spice that killed him came from the Gas Pipe. But Amy and Jerry never bothered to check. Instead, in a series of office communications around that same time, Gas Pipe employees were busy lauding the fact that the new stuff they were mixing in tubs in the back room was stronger than anything they had previously carried in the store.

“The Court asked earlier what efforts were taken by them to make their products safe, and the answer is none,” Meacham said at the hearing. “None. They knew how dangerous it was, and all they strived for was more potent drugs, more sales, more money. There’s not one thing that I could find in this discovery, and they haven’t raised it either, that they tried to find out what drug killed that kid and make sure they didn’t sell it or [said], ‘Let’s back off the potency and not sell some things that are so strong.’ Not one.”

Judge Lynn knew the easiest and perhaps most just thing would be to follow Meacham’s urging and sentence Amy and Jerry to the full 60 months, which would put them on par with the Gas Pipe store managers who, unable to afford expensive legal counsel, had entered guilty pleas. But as with everything in the case, it came down to a difference at a molecular level. The guilty pleas meant that, as far as the law was concerned, the employees had sold illegal narcotics. But a jury had determined that Amy and Jerry had not. And for her part, Judge Lynn was unwilling to take acquitted conduct into account because it would effectively be a violation of the Constitution’s guarantee of due process.

“The Court is not the judge of morality,” Judge Lynn concluded. “That’s the job of the real judge. I’m the judge of legality. In my heart, I wanted to punish you for more than the statute allowed because I disapprove so strongly of what you did, and I can’t do that. I’m not going to do that, and I’m not considering at this juncture sentencing you to the statutory maximum either. I’m very mindful of the fact that your employees lined up one after the other and pled guilty to what the jury acquitted you of, and that some of them are serving more time than you are even exposed to because of that, and that’s your fault.

“They made decisions to plead because they did not want to take the chance of going to the jury, and you showed courage in going to the jury, and you were correct in that you were acquitted of the more serious of the charges, but what you did is very serious. This isn’t just a minor offense that you were convicted of. The jury could have acquitted you of all of it, and they didn’t because it was quite apparent that these things are labeled one way and they were intended for something else entirely. And they are products that in the Court’s view, based on the evidence before me, is dangerous and addictive. And similar, very similar products have resulted in, in the Court’s assessment, deaths and serious injuries in our community, and that was put out in commerce with false identifiers for the sole purpose of selling it. That’s what you did. And you said you own it, and it’s good because that’s what you did, and this is the day of reckoning for all of that.”

The reckoning was this: Amy and Jerry were each sentenced to 36 months of incarceration. The plan was to stagger the sentences to overlap for just one year, with Jerry going first due to his age and poor health, so they could continue to maintain their businesses.

Jerry began serving his time in November, then the coronavirus infiltrated the federal prison system. Along with a number of other nonviolent offenders, Jerry was released on May 20. Amy is still scheduled to start her sentence a year from now.

According to the judge, the reason they will end up serving less time than most of their co-defendants was due to their courage and willingness to cast their fate with a jury. But it really had more to do with money and hubris.

Amy and her dad chose to fund extensive legal defense teams, believing that a jury of their peers would see their actions the way they had, as a smart business decision that skirted the line of corporate malfeasance. They weren’t drug dealers; they were savvy business executives who had discovered a lucrative new product line. Dangerous, sure. But certainly they were in good company with the likes of Philip Morris, Purdue Pharma, and Juul.

Those companies, too, have always kept the drugs in plain sight. And they, too, have used mislabeling and misleading advertising to normalize the ingestion of harmful products. Any resulting deaths are simply an unintended cost of doing business. Yet none of those executives has gone to jail.

So maybe that was the real hubris—not the fact that Amy thought she could escape unscathed, but the fact that Amy ever believed she was like those other executives.

She was the outsider all along.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author