On a cold Thursday in January, I volunteered to help with a one-night homeless count, a federally mandated effort that takes place in cities across America. In East Dallas, our small team didn’t fare well at first. We found a pack of yipping coyotes running through a meadow at White Rock Lake, but hours into our shift, we hadn’t found a single homeless person. I knew of a homeless camp off Garland Road, near the spillway. Though it lay just out of our assigned zone, I persuaded the group to venture into the darkness to see if anyone was there.

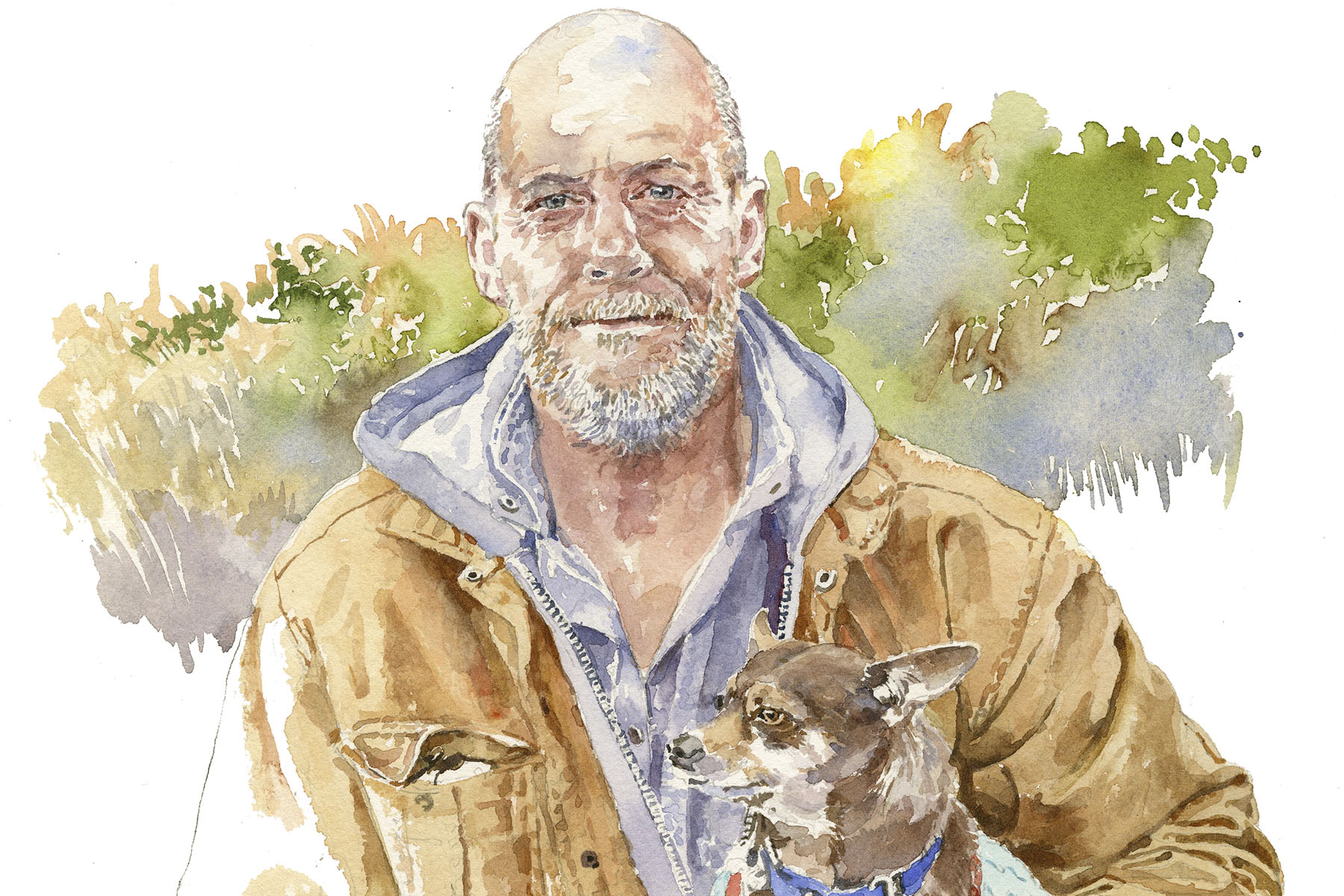

That’s where I met a man named Bart. Bart has a Chihuahua named Lacy Suzanne Rodriguez Jalapeño-on-a-Stick, and he had a joke for every question I asked him. He told me that in school he failed every class but girls. He has a twin brother he sees on holidays.

Originally from Blue Ridge, north of McKinney, Bart and much of his family lived in and around East Dallas, where he feels most comfortable today. For the last eight years, he said, he has lived around the creeks and culverts that spill out of the southern end of White Rock Lake. At times he camps deeper in the woods, along White Rock Creek, but he usually sets up closer to the QuikTrip on Garland Road.

Bart is trim, balding, and missing a few teeth. He is a great storyteller and balances descriptions of intense confrontations with sarcastic asides. His hands are calloused and adorned with several silver rings, a juxtaposition that makes sense given his years as a homebuilder and desire to maintain a sense of normalcy while homeless.

Bart makes choices that suit him. He said he doesn’t miss the sedentary life he once lived. “I went to work, and I sat in front of a TV after I got off for 20 years,” he said. “And when I left, I haven’t watched TV since.”

When we sat down at his camp, he made it clear that he was doing just fine. “I tell people that if you ever want to experience total freedom from any worry in the world or anything, become homeless,” he said. “And you know what? I wouldn’t trade this experience for anything.”

Bart’s “camper” is a testament to his resourcefulness. He sleeps with Lacy Suzanne Rodriguez Jalapeño-on-a-Stick in a sleeping bag on 8 inches of memory foam atop a long pallet on wheels; it’s framed with lumber and protected by tarps. Think of a small covered wagon. The wheeled pallet includes an awning under which sit numerous plastic crates filled with foraged and purchased food. He said he gets free fountain drinks and food from QuikTrip and half-price meat from a nearby Tom Thumb. He can load all his belongings, including a snare drum he is learning to play (“I missed my calling,” he said), on his covered wagon and pull it with a fat-wheeled minibike if he needs to move quickly.

Bart called himself a professional dumpster diver and said he has found everything from sex toys to Bluetooth headphones. The good stuff turns up in apartment dumpsters after evictions. Staff at the Goody Goody on Garland lets him charge his phone and other electronics, including a security camera he trains on his camp.

Bart said he is prepared for a dystopian future. “If anything was to ever happen, like a major catastrophe or something, I know what to do,” he said.

Bart said he is prepared for a dystopian future. “If anything was to ever happen, like a major catastrophe or something, I know what to do,” he said.

The purpose of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s annual Point-in-Time Count is to help cities and nonprofits allocate resources. Call it a homeless census. My team was armed with questions about how the person became homeless, whether he had been a victim of abuse or was in the foster care system, if he was a veteran or had HIV.

Skyrocketing housing costs and NIMBYism have made affordable housing scarce in Dallas. According to the Metro Dallas Homeless Alliance, to support its homeless population, Dallas needs to add more than 400 beds in permanent supportive housing, such as public housing facilities or long-term voucher programs for special needs populations, including seniors, veterans, and the disabled; more than 1,000 beds in long-term rapid rehousing, which generally includes rental subsidies and supportive services for more than six months; and more than 4,000 beds in short-term rapid rehousing, which includes rental subsidies and supportive services for six months or less.

To learn how to reduce the homeless population, Dallas might do well to look to its neighbor to the south. Houston has targeted veterans and added housing with increased federal dollars, more than doubling the funding Dallas received from HUD. Since 2011, Houston has reduced its homeless population by 54 percent; over the last three years, Dallas’ sheltered homeless population has increased by 16 percent. Dallas now has a larger homeless population than Houston, despite having about 1 million fewer residents.

But Dallas is starting to make some moves that could improve the situation. “We are making a plan to get the community as a whole working efficiently,” says Kenn Webb, a lawyer on a strategic planning task force established by MDHA who was also the first chair of Dallas’ Citizen Homelessness Commission. “We are making sure people are on the same page and making sure they aren’t working at cross purposes.”

Dallas voted in 2017 to issue $20 million in bonds to go toward homeless housing, but after a plan in Lake Highlands was met with community backlash, that money remains unspent—this despite a successful conversion of a senior living facility to homeless housing just outside Lake Highlands called the St. Jude Center. Research has negated the argument that homeless housing lowers home values or increases crime, and the St. Jude facility has been well received by its neighbors. “Now that the community is open, the surrounding community realized these folks are just like me,” Webb says. “They needed a place to live, and now they have it.”

Bart, though, resists housing and homeless shelters. He wouldn’t be allowed in one without putting Lacy Suzanne Rodriguez Jalapeño-on-a-Stick in a kennel, a nonstarter. Beyond that, he doesn’t want to give up his freedom. “I couldn’t do it,” he said. “I’ve been out here so long and I’m so used to being outside in it that I don’t want to get back inside. And I don’t want somebody to have their thumb on me anymore. I tell people, ‘You know what I have to do tomorrow? Not a damn thing if I don’t want to.’ ”

Bart said he lived with a woman and helped raise her children for 20 years before he became homeless. “She wasn’t very pretty, but I loved her,” he said. “And I was a lot better-looking than I am now. Trust me. I had all my teeth and some of my hair.” After the breakup, he struggled to find work and lived in his truck until he couldn’t afford his insurance, so he sold the truck and headed to the woods.

It hasn’t been easy. Several times his belongings have burned (he uses fire to stay warm) or washed away (a hazard of living beside a creek), and he keeps an eye out for the snakes that populate the urban forests. But he said he prides himself on not asking anything of anyone.

“The us-them attitude is something we need to get past,” Webb says. “The question isn’t what to do about the homeless or really even what to do for the homeless. The question ought to be: what can we do together to make Dallas a better place to live for all of us, including those who have the most urgent needs?”

As I ducked out from under his awning, Bart told me what I already knew after spending some time with him. “Don’t judge a book by its cover,” he said. “Just because we are homeless doesn’t mean we are all bad people.”