That had, more or less, been his original idea. Officially, he is on the first day of his usual extended holiday break from his afternoon-drive show, The Hardline, which he has hosted for the better part of 26 years. Only Rhyner and a few others know that he isn’t planning to return to work when the holidays are over, and even he isn’t certain. But he’s close enough. He decided to film a video on his phone, announcing his retirement from The Hardline and The Ticket, the sports-talk station that he helped found in 1994, and he figured if he was still set on leaving in a few weeks, he would post the video to his social media accounts.

And maybe that would have been fine if Rhyner were just any old radio guy. But he was a member of the Texas Radio Hall of Fame, for a start, which speaks to his importance if not quite his influence. His name belongs among the greats of Dallas radio, groundbreaking personalities like Ron Chapman and Kidd Kraddick, Glenn Mitchell and Gordon McLendon. He didn’t invent the all-sports station, but he did invent this version of it, one as invested in the off-air lives of its personnel as it is in the on-field exploits of the players they cover. Over the years, that version has spread across the country as other stations adopted the guy-talk format. Jeff Catlin, who started as Rhyner’s producer and is now The Ticket’s program director, says a station in Utah even named its afternoon show The Hardline.

None of them could replicate it exactly, of course, because they didn’t have Rhyner. He is in the marrow of the station. The other Ticket hosts use his lingo, carry nicknames he bestowed on them. Some have careers because of him. He wasn’t solely responsible for its success, but the station mostly sprang from his head a quarter-century ago, as if Zeus had been a Texas Rangers fan. And it is hard to overstate the impact it has had locally, where the language he introduced over The Ticket’s airwaves has fallen into common usage, even by people who aren’t listeners.

So when he told his ex-wife Renée (whom he’s still close to) and his daughter Jordan about his exit strategy in November, they weren’t about to let a moment like that be relegated to a shaky iPhone video.

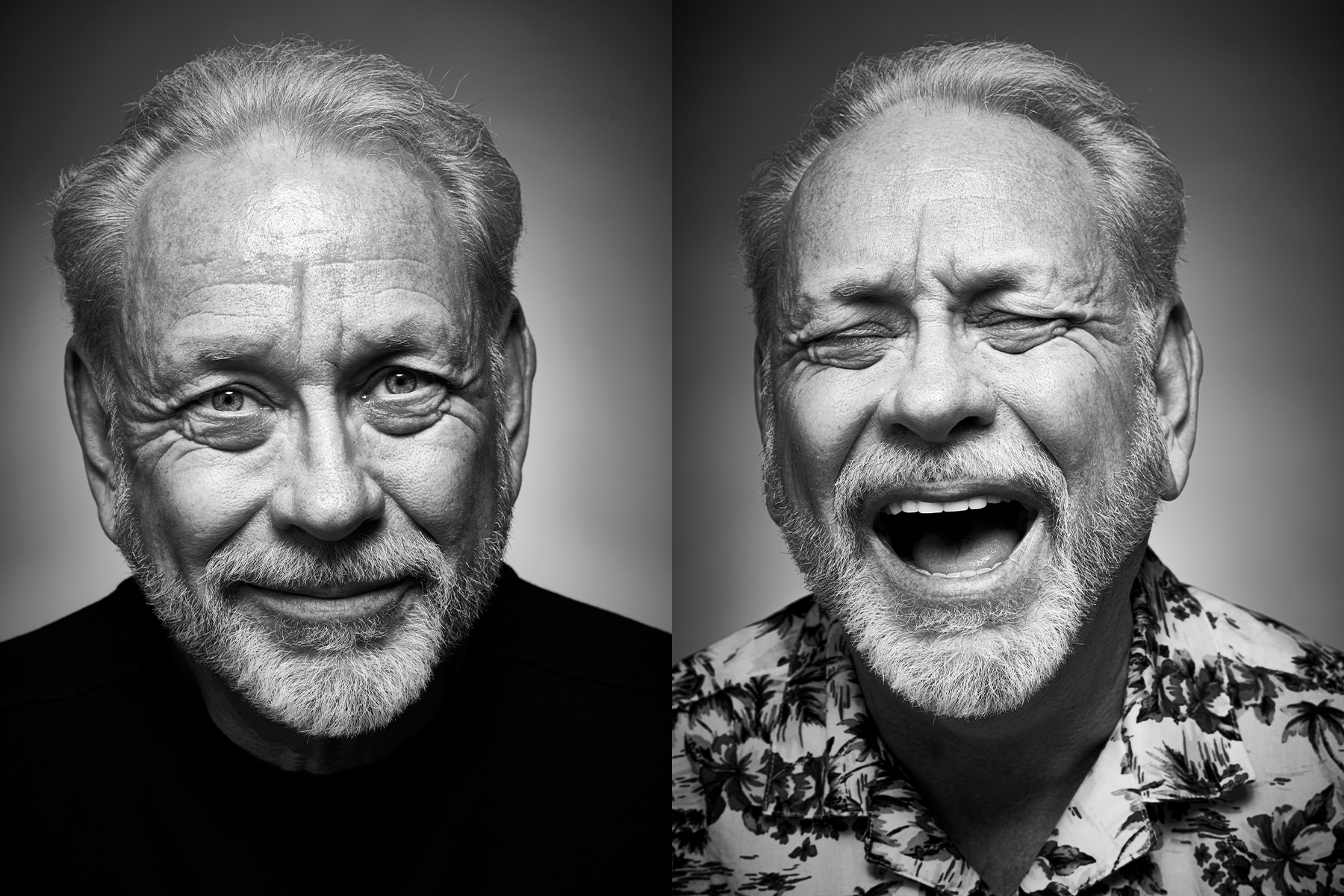

Jordan, who worked as a producer for FremantleMedia (the company behind American Idol and America’s Got Talent), took over. She hired Elizabeth Lavin—whom they had known since 2014, when she shot a portrait of Rhyner for a D Magazine story on the occasion of The Ticket’s 20th anniversary—to shoot the video. She was only available the day before his colonoscopy, so Rhyner is here, in a hallway of his building, delivering his seven-minute speech over and over, his stomach full of Jell-O. “I cannot stand Jell-O under any circumstance,” he says.

Hands clasped in his lap, he begins again, for the sixth time, or maybe seventh. He has lost track, but he knows it’s the last one. He doesn’t have another in him. He is hungry and cranky and wrung out from repeatedly saying goodbye to the world he’d known for more than 25 years, his greatest professional accomplishment, his life—admittedly sometimes more of his life than it should have been.

In that familiar, avuncular growl, the man long known to listeners as The Old Grey Wolf speaks to the camera. He says it is time for him to leave and it is his decision. “I will miss it terribly,” he says and then thanks the listeners before hitting his standard show-closing line: “So, until we meet again, stay hard, keep jamming, and we’ll see ya.” Then he gets up and walks down the darkened hall and through a door at the end, presumably into his next life.

It’s a nice grace note to an elegant video, a mature farewell from the godfather of the station that announced its presence on the scene with a giant jockstrap on a billboard.

And then, almost a month later, when it was finally time to make his decision public, Rhyner posted the video half an hour early, turning his Irish exit into a jailbreak. (He says he made it look accidental, but it was on purpose.) The Ticket’s air staff—most of whom had only learned he was leaving that day—had just watched the announcement together and were talking strategy, how they would handle the big reveal. Then longtime Hardline producer Danny Balis walked in, laughing, saying that the video was already online. They spent the rest of the day scrambling to catch up with the breaking news, which had eclipsed news of the Cowboys hiring a head coach, never completely getting in front of it. It was the perfect ending.

And we’re back. It’s just after lunchtime on January 28, the week before the Super Bowl. Normally Rhyner would be in Miami with the other Ticket hosts. Right now, he’d be recovering from whatever high jinks the group instigated the night before and preparing to host The Hardline from radio row. Instead, he’s at City Tavern on Elm Street, in downtown Dallas, and the game is barely mentioned. “This is the first real acid test,” he says.

It has been three weeks since Rhyner stunned listeners and colleagues with the retirement video. A few days ago, though, was perhaps the real first acid test. He went back on the air for the first time, rejoining The Hardline for a few segments to celebrate The Ticket’s 26th anniversary.

“It was fun, it was nice, and when it was over, it was over,” he says. “I went about my business.”

So, no, he doesn’t regret his decision to leave. That is not to say that he doesn’t have a few regrets. But those he had already.

“This place was full of vibe. God, it was just electric. I hated walking out of there every day because, hey, man, what am I going to do now?”

During most of his run at The Ticket, Rhyner was known on air—and sometimes off, depending on whom he was talking to—for his occasional impatience, his low tolerance for small talk or bullshit of any kind. “Well, it sounds like you’re about as interested in this interview as we are, Kenny, so we will let you go and we thank you for your time,” he said to Kenny Lofton during spring training in 2007 before abruptly hanging up on the Texas Rangers outfielder. When I think of Rhyner’s voice, and I don’t mean to reduce him, I hear him growl: “What else?”

He has mellowed now, a change that happened fairly recently, when he sat back a few years ago and realized: Hey, man, you’ve won the game. He admits he had an edge to him all that time, even after turning The Ticket into a radio juggernaut, a cultural force and critical and commercial success (three Marconi Radio Awards from the National Association of Broadcasters for Sports Station of the Year, No. 1 in the prime males 25-to-54 demo for more than a decade, as of last year). Even after it made him rich and a radio hall of famer. He seemed to live his life guided by those two words—What else?—always pushing forward, never lingering too long, maybe not even enjoying everything as much as he should have.

I bring up probably the most infamous display of that edge: his on-air interaction with a substitute host named Pete Stein, a snippet of audio the station has played repeatedly for more than a decade. After Rhyner grew tired of talking to him, he counted down as if he were about to launch a rocket—five, four, three, two, one—and ended by saying, “You’re done.”

“He didn’t deserve that,” Rhyner says. “He was just filling in, trying to do a thing. He was probably just thrilled to be on the air with us. I didn’t feel bad about it at the time. But I kind of do now. If I ever see that guy again, I’m going to make it right. If I can, if he’ll let me. He may not, and if he doesn’t, that’s OK, too. That’s just what I’m going to have to live with.”

The question is still there—What else?—but now it has a different slant, no longer about what he needs from his life but what he wants from it.

And we’re back. It’s 1979 and it’s time for Rhyner, as he says, to go find his life’s work. “Though at that time, a) I had no concept of what that meant, and b) I had no idea ever that this would be it.”

Without much of a plan, for the future or the present, he was “eaten up with the idea of getting into radio.” He was 29 and drumming in bands, and where was that taking him? Not nowhere, but not where he wanted to be. He had an ex-girlfriend who had gotten involved with Ken Rundel, the news director for KZEW-FM, The Zoo, and she told Rhyner that he was looking for someone to help around the infamous rock station. Rundel was on his way out, going to law school, and needed someone to do the tasks that he would normally do but couldn’t. “Which is a little bit nicer code of saying, ‘I need somebody to do my shit work for me,’ ” Rhyner says.

He was happy to oblige, doing whatever was asked just so he could hang around. “I was so charged up to be there,” he says. “This place was full of vibe. God, it was just electric. I hated walking out of there every day because, hey, man, what am I going to do now?”

Rhyner caught the eye of the program director, Tom Owens. “He realized he had a puppy dog on his hands who would do anything for anybody at any time, day or night, whatever anybody wanted,” Rhyner says. Owens put Rhyner in charge of his research and development department, which amounted to calling record stores and asking what they were listening to—“real shit work.” But he was happy to do it. It kept him involved.

And because he was involved, because he was always around, an opening he wasn’t even looking for presented itself, a producer slot on the popular Morning Zoo, writing news scripts for hosts John Rody and John LaBella. Eventually he joined them on the air. He wanted to be in radio, not necessarily on the radio, yet there he was. And once he was on the radio, after a while, he wondered what the next step was. Where did he go from there?

What else?

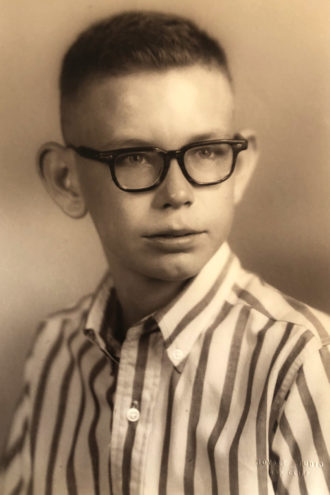

“I was always a radio nut,” Rhyner says. “Even as a kid, I was a radio nut. All my friends were watching My Mother the Car or whatever, and I was back there listening to Russ Knight ‘The Weird Beard’ on KLIF and it was magic. It seemed like he was talking to everybody.”

This would have been when he was growing up in Oak Cliff with his parents and his younger sister, Pattie. It was a time, in the 1950s and ’60s, when back doors stayed unlocked and Saturday nights they’d have parties with the neighbors, his mother, Dannie, and her sister Lois playing songs on the piano by ear while everyone sang along. “It was really Leave It to Beaver,” Pattie says.

The siblings are “incredibly close” now, she says, but back then “it was mostly by force.” “He forced me to play baseball games with him,” she says. “But it turned out OK, because I’ve been in business development most of my career, and I’ve gotten in a lot of doors because I could recite the starting lineup for the 1960 Chicago White Sox.”

“Probably our biggest touchstone is she’s musical, too,” Rhyner says of his bass-playing sister, “except she’s a lot better at it than I am.” That has always been his opinion of their dynamic, even now, as he’s nearing 70. Pattie was the achiever and he was not. “I was the fuck-up,” he says.

Pattie says that was mostly because she wasn’t allowed to be. “One of us had to be a good kid so that our parents didn’t go crazy.”

Rhyner used to joke about getting his hands on a bus and inviting Ticket listeners to take a tour of Mike Rhyner’s Oak Cliff, going by the houses he used to live in, all the neighborhoods—“a couple of which are nowhere you’d want to be these days,” he says. He wishes now that he had taken the idea seriously, really gone through with it. “That would have been fun.”

The family started out on the southeast side before moving west, near Kimball High School, where Rhyner graduated in 1968. His parents, he says, were “country people.” His mother grew up in Alvarado, south of Fort Worth, and his father, Howard, in Saltillo, an unincorporated speck about two hours east, on the way to Texarkana. His dad’s family eventually moved to Dallas, settling on McKinney Avenue, and the elder Rhyner went to North Dallas High School when the neighborhood just north of West Village was still considered North Dallas. “Occasionally, when I’m over there, I’ll be thinking, You’re on your dad’s turf here,” Rhyner says.

But mostly he remembers his parents being leery of North Dallas, of anything outside of Oak Cliff, really. “They were Oak Cliff through and through,” he says. His dad was in insurance, and his mom stayed at home, raising the kids, and later became a secretary for DISD. “Awesome cook, looked after shit, kept things so squared away around there. I loved that woman something serious,” he says. “I’m a mama’s boy for sure. I may be a lot of things, but if you’re going to make a list of the shit I am, put ‘mama’s boy’ on there. Because I definitely am that.”

It’s probably no surprise, then, that Rhyner never strayed too far. He lived in Arlington briefly, during his short stint with WBAP in the late ’80s, but otherwise he has been in Dallas. Pattie left for California a long time ago. She guesses her brother has spent a total of a year and a half outside of the city his entire life.

“I don’t think Dallas could have a bigger champion than Mike,” she says.

And we’re back. It’s January 1985 and the future Renée Rhyner has just gotten hired in the sales department at KZEW. Renée says that her ex-husband always tells her she could have had a future in the radio business if they hadn’t started dating.

Part of her job was selling remotes, live broadcasts from whatever location would pay for them. Renée would have to go there, too, to collect the money, “sometimes at, like, dive bars off Northwest Highway,” she says. “People wouldn’t even pay me until after the promotion, and I would have to go in the back office.” Rhyner stayed with her at a remote one night to make sure she was OK. “So that was a very gentlemanly thing to do,” she says.

“One time she told me that she likes the games,” Rhyner says, “but the thing she really missed most was just having the sound of baseball on in the house.”

rn“I think he’s just surprised that I could easily sit down and watch a baseball game by myself for three hours,” Jordan says.

But they didn’t know each other very well. At another remote, the night before Valentine’s Day, they got to talking, and the next morning, when Renée arrived at her desk, there was a note underneath the phone. “His wording—he’s a journalist by nature—I’ll just never forget that little note,” she says. “At the end, he’s like, ‘And how remiss would I be if I didn’t say, “Happy Valentine’s Day”?’ ‘Wow. Remiss.’ And then every morning there was another note. Sometimes pieces of oranges.”

Pieces of oranges?

“Little orange slices. And I remember being with him, going, ‘If you ever think that this is going to lead to us dating, that’s not going to happen.’ But he just won me over with his cleverness. I mean, his personality. But, no, my career did not last long there. Yeah. It was really hard, anyway. Sales in radio is hard, especially when you’re first starting, because they just basically give you the phone book.”

Renée ended up having a bigger impact on local radio after leaving KZEW. She was the one who came up with the name The Ticket. But Rhyner says the business eventually became a problem for her again, or his part in it did, anyway. Though it’s clear from talking to both that they love each other, despite the fact that they’ve been divorced for more than a decade. “A lot of it probably just had to do with me just getting too eaten up with my job, my work, what I did,” he says. “It turned into a little bit too much all about me. And I didn’t take responsibility for that.”

It’s July 1990 or maybe August—no one can remember exactly—and we’re at old Arlington Stadium, the former home of the Texas Rangers, bigger but not much better than it had been when it was a minor-league ballpark called Turnpike Stadium. Arlington Stadium had an auxiliary press box—on the roof, down the first base line—where they stuck the radio reporters, who called it “the back of the bus.” It is, as the legend goes, where The Ticket started.

Craig Miller had just gotten a job at KRLD-AM and found himself seated behind Rhyner. Miller remembered him from his days at The Zoo, but Rhyner was working for something called GTE On Call then, delivering sports reports over the phone for a call-in service that is hard, today, to imagine.

Soon enough, Miller and Rhyner gravitated toward each other, along with Greg Williams from WBAP, spending the entire time talking, sometimes about the game, sometimes not, sometimes keeping the conversation going over a beer afterward. Rhyner nicknamed Miller “Junior” back then, not necessarily because he was younger but just because he thought the group needed a Junior.

“That’s four hours, maybe, in a baseball game,” Miller says. “I guess we all found each other interesting or weird or whatever. And so, yeah, pretty quickly the three of us were thick as thieves.”

As the trio was growing closer, spending their summer evenings performing an ad hoc talk show for their fellow reporters, Rhyner was approached by Geoff Dunbar and then reached out to Spence Kendrick about starting a 24-hour all-sports station, Dallas’ first. He was tasked with putting together a roster, and he already had his first two names.

“I knew that the only way that this thing would ever work was for us to differentiate ourselves in some way. And that—guys being guys—seemed to be the way to do it,” Rhyner says. “And it just so happened, in probably the craziest cosmic confluence of all of this, that at that time, about the time I started thinking along those lines, I was around guys who I thought could do that. And Craig was one of them. Greggo was another. I thought those guys were very capable of something like that.”

Until Petty Theft—his Tom Petty tribute band—played its first show two days before Christmas 2003, Rhyner hadn’t played a gig with any group since the very early ’90s and hadn’t taken it too seriously since long before that. He thought music was behind him, a chapter of his life he had closed and walked away from. What brought him back?

“Stupidity,” he says.

Rhyner had been in bands that played covers before. If you were in a group around Dallas in the 1960s and ’70s, that’s what you did. He had even, infamously, decided against letting a young Stevie Ray Vaughan join one of those bands back in school, because Stevie didn’t know any Beatles songs.

But he’d never been in a tribute act before, performing the songs of only one artist, and he’d almost always been the drummer, not the frontman. It was all new terrain.

On a surface level, choosing Petty made sense. “I looked at him, and I looked at them, and I thought, This looks like something I’ve seen before,” he says. “The way they went about their business, the alignment of the band. Guitars, keyboards, bass, drums—that’s it. That’s kind of like the things that I did.”

But it goes deeper than that. There are plenty of parallels when you start looking for them, not the least of which is the fact that they were almost exactly the same age, born 65 days apart in 1950, the perfect time to fall under the spell of rock and roll. “And while he was over in Gainesville, Florida, getting his scene together, playing in teenage bands and doing gigs and doing frat parties and doing this, doing that over there,” Rhyner says, “that’s exactly the same thing I was doing here.”

Deeper: in 1979, Petty was fighting with his record label over his contract and betting on himself, going so far as to declare bankruptcy and hide the tapes from the label at the end of each recording session. It resulted in his breakthrough Damn the Torpedoes. That same year, Rhyner was betting on himself, too, throwing himself into a new career that finally got him to somewhere near where he’d been striving for since he first joined a band. And 1994 was again a turning point for both men. Rhyner redefined himself with the debut of The Ticket and The Hardline, and Petty reinvented himself with the Rick Rubin-produced Wildflowers. It was the beginning of two prolific second acts.

In a way, Rhyner had been covering Petty his entire life. So it would be hard to imagine that he didn’t feel a slight tug of mortality when Petty died in 2017, even if he weren’t in a band, singing the man’s songs. It would be hard to imagine that he didn’t think of Petty’s last years—when he was in so much pain that he had to be carted around backstage and lifted onstage to perform—and didn’t hear that question in the back of his mind again: what else?

Bryan Curtis was a junior in high school in Fort Worth when The Ticket debuted. He remembers, as the station’s premiere neared, 1310 AM ran on a loop a recording of the hosts saying their names; he and his friends would sit and listen to that, he says, so desperate were they for the debut. He set his alarm so he would be up and listening the moment the station went live. “It was that important,” says Curtis, now an editor-at-large at The Ringer, a sports-and-culture site.

He didn’t know Rhyner from his Zoo days. Curtis and his friends were attracted to The Ticket for the sports content, not the names associated with it. But Rhyner soon loomed large in their life.

“I feel my parents’ generation drove around listening to people like Wolfman Jack, and my generation, or at least the very nerdy kids I hung out with, drove around listening to Mike Rhyner and The Ticket guys,” Curtis says. “They played the same role. They were the people teaching you the correct take on events, and they were your friends. And they were cool as hell.”

Curtis still feels the impact of Rhyner and The Ticket guys long after leaving Dallas, most notably in the way he speaks. He’s not alone. For many people who grew up listening to The Ticket, and even those who just grew up with people who grew up listening to The Ticket, it has become a sort of regional dialect.

“It is not overstating it to say they created a completely new language,” he says. “When Mike announced his retirement, a buddy texted me and said, ‘How much of my daily speech do you think comes from Mike Rhyner?’ And I wrote back and said, ‘90 percent and the other 10 percent comes from [morning host] Gordon Keith.’ It’s totally true. When I was living in New York, we’d sit around in Brooklyn, those of us from DFW, and we’d just use Ticket-isms—not even self-consciously. You just use ’em all the time. Like, ‘stop down.’ ”

Or “wheels off” or “spare.” “Spare was a term that was thrown around in a band that I was in, in 1973,” Rhyner says. “In the lexicon of that band, it was spare this, spare that—it was kind of part of the hippie vernacular back then: spare change, man. And it evolved to spare guy, spare this, spare that. And at The Ticket, if somebody was really bugging you, it was like, ‘Man, he’s sparing me to death.’ But, yeah, it made the transition with me from there.”

Probably Rhyner’s most well-known contribution to the discourse is “P1,” a term that was and is still used throughout the radio business. It stands for “preset, or preference, 1” and refers to listeners of a particular station who reserve that button on their car radios for their favorite station. Rhyner didn’t come up with the term or the meaning. But he liberated it from the world of technical radio jargon. He used it at first as a lark, part of the meta approach The Ticket used, especially in the beginning, when consultants told him to stop doing it.

“They came in self-consciously not having big opinions, putting air quotes around sports opinions,” Curtis says. “It was a bit like Letterman to your regular late-night show, or Jon Stewart, right? Like, this is the best sports show, but it’s also a parody of a sports show.”

With P1s like Curtis and others migrating to other parts of the country, for college and then the rest of their lives, you can bet there is someone in, say, Chicago who considers himself a P1 of a certain pizza place in Wrigleyville and has no idea that he’s saying it now only because Rhyner popularized it in Dallas a couple of decades ago.

And we’re back. It’s January 24, 1994. The original Ticket lineup had Rhyner and Williams on from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m., followed by Miller and his college roommate George Dunham from 2 to 5, a show that would eventually come to be called The Musers. (Rhyner had actually met Dunham before any of the others, back in his Zoo days, when he judged a battle of the bands in which Dunham’s group Pegasus was involved.) Dunham and Miller went to lunch before their show, mostly so they could be in the car for the first minute of The Hardline.

“I’ve never heard anybody that sounds like Mike or Greg,” Miller says. “And we’re sitting there listening to them come through the speakers in the car and they each had these identifiable voices, and in the first three minutes they had funny lines and hot opinions, and George and I just looked at each other and we were like, This is going to work.”

And it did, for almost 13 years, before Williams’ drug addiction led to his permanent exit from the station in December 2008. Rhyner isn’t much interested in relitigating the end of their personal and professional relationship. “Somewhere along before it actually came down, I’d mentally signed off on him,” he says.

Williams was replaced by Corby Davidson, who had previously filled a role on the show similar to the one Rhyner had with The Morning Zoo, and The Hardline kept going. Rhyner kept going, because he always kept going.

What else?

In the early years of The Ticket, Rhyner would sometimes go to lunch with Miller and Keith, who briefly worked on The Hardline. They were little brothers to him as much as colleagues, but there was always a slight gap to bridge. Occasionally, talk would turn to retirement, what they would do when they didn’t need to work anymore. Keith and Miller practically lusted after the idea, but Rhyner wouldn’t hear of it.

“Every time that Junior and I would be daydreaming about retiring and amassing enough wealth to actually retire someday,” Keith says, “all these great plans and dreams that we laid out in front of us like shiny silverware, Rhynes would always cut us short and say, ‘No, you’d hate it if you retire.’ We’d be like, ‘Why? We just spent 15 minutes on the things that we’d love about retiring.’ He goes, ‘Yeah, but you wouldn’t be relevant. You wouldn’t be relevant. What are you going to do every day?’ ”

It’s an attitude common among the postwar generation, where your occupation, as Keith says, “it gives you purpose, it gives you form.” Rhyner was certainly defined by what he did. But where he did it was just as central to him.

“I knew that the only way that this thing would ever work was for us to differentiate ourselves in some way, and that—guys being guys—seemed to be the way to do it.”

He had found a place like The Ticket once before, at The Zoo, where the line between vocation and avocation was blurred, a home more than an office, and then that had been taken from him. He left the station in 1986 after it was sold, knowing the end was near (it stopped broadcasting a couple of years later), and he bounced between frequencies until The Ticket’s launch in 1994, stuck in the static. WBAP let him go the day after his daughter Jordan was born, in 1988. He hustled to make money as a freelance writer, including a weekend music notes column he wrote for the Dallas Morning News for a few years.

It is easy to see why it was hard for him to leave another home, why he wouldn’t even consider it for a long time, why he lasted through both a personal and professional divorce, through offers from other stations, through The Ticket changing ownership a few times, through meddling consultants, through the general erosion of time.

“I’ve been burned by the fire,” Petty sang on “Insider.” “And I’ve had to live with some hard promises/I’ve crawled through the briars/I’m an insider.” That was Rhyner. He had made it and he didn’t want to be on the outside again.

“I always pegged him as the anti-retirement guy,” Keith says. “That’s why it was surprising to me that he did it, because I think he enjoyed doing that show, having that job and that position. So, we’ll find out if Mike was right then or Mike is right now, when he comes back in two weeks and says, ‘God, I hate this.’ ”

And we’re back. It’s January 6 and Rhyner’s colleagues finally see what he did. He had already said goodbye, a month earlier, only almost no one had caught it.

Throughout his last broadcast as a host, back in early December, Rhyner had tipped his hand with the songs he played as the show returned from commercial. Each time he played one, he’d try to catch the eye of his co-host Davidson or producer Balis to see if they were picking up on it. But he never saw a glimmer of recognition. After the show, he tweeted the list of songs and posted it to Facebook, same as he always did, and still nothing. Jordan even responded to her father’s tweet, pointing out the clear theme, and no one noticed.

On the Monday afternoon after Rhyner posted his video, as Davidson and Balis discussed their colleague and friend’s departure, still in shock since they’d found out not long before the rest of the city had, someone brought his list of return cuts to their attention, and Davidson and Balis, at long last, saw what he’d done: “Let’s Go,” The Cars; “Goodbye to You,” Scandal; “So Long,” Firefall; “Everytime You Go Away,” Paul Young; “Time to Move On,” Tom Petty; “Fade Away,” Todd Rundgren; “I’ve Had Enough,” The Who; and “It’s Over,” Roy Orbison.

“I’m getting chills,” Balis said on the air, as he read the list.

And we’re back. It’s two years ago and Rhyner is getting to see what his future might look like. More baseball, more Jordan, more time being a dad than the host of The Hardline.

When Jordan was growing up, Rhyner always had Rangers games on at home, or some other game if they weren’t playing. She didn’t seem particularly interested in what was going on, and that was fine. He wasn’t going to force her.

Shortly after Jordan graduated college at the University of Southern California, though, she started paying attention, asking him questions. It helped that the Rangers were getting good, rounding into the team that would go to two World Series. He taught her how to keep score. Rhyner had gotten a gift he never expected: a baseball girl. “I think he never thought that was out there for him,” Renée says.

Not long after her arrival in Los Angeles, Jordan called her father and told him she wanted only one thing for Christmas. “I want the package,” she said. The package? What was that? “You know, the one where you can watch any baseball game.”

“I was just like, ‘Holy shit—really? You want that?’” Rhyner says. “One time she told me that she likes the games, but the thing she really missed most was just having the sound of baseball on in the house.”

“I think he’s just surprised that I could easily sit down and watch a baseball game by myself for three hours,” Jordan says.

So, anyway, two years ago: Jordan was turning 30 and Mike wanted to take his baseball-loving daughter to see some ballparks. He told her to pick three that she had always wanted to see, and Jordan came back with Yankee Stadium in New York, Fenway Park in Boston, and Wrigley Field in Chicago. At Wrigley, they wound up in the second row thanks to a marketing guy he met through Davidson. “It was incredible,” he says.

The ballpark tour cemented a father-daughter bond that began before she even knew it was happening.

“Maybe we get to do more of that now that he’s retired,” she says.

It’s February 26 and I am getting the tour of Mike Rhyner’s Oak Cliff, in his red SUV instead of a bus. Rhyner shows the three houses he lived in, the garage where Stevie Ray Vaughan’s audition happened, the backyard where his dog, Ring, lived a pretty miserable existence, tethered to the garage because Howard Rhyner was too cheap to have a fence built. We pass T.G. Terry Elementary and Rhyner sings me the school song. There is Kimball High, where he had his 50th class reunion two years ago; he found three of his old lockers and remembered two of their combinations. We try to find one of Vaughan’s old homes but get turned around a couple of times and give up. We drive by his favorite Mexican restaurant, Tachito’s.

As we wind around the southern sector of Dallas and he tells me stories, relays fun facts, I realize that one of the most important things The Ticket will miss with Rhyner’s departure is his deep knowledge of the city. Most of the other hosts live in the suburbs, and the ones who don’t didn’t grow up in Dallas. They can replace Rhyner on the roster—and they have, moving Bob Sturm from afternoon’s BaD Radio to team up with Davidson—but they can’t replace that.

We start to make our way back to downtown. We’re listening to KLUV HD3, a station he says he has been loving lately. “I’ve given up on music radio totally,” he says. “All I want is just something, every now and then, that I haven’t heard in a long time or that I don’t hear very much. And they deliver that in droves.”

“Dissident,” a song from Pearl Jam’s Vs. album, comes on. He says he’s not familiar with it, and I haven’t listened to it in forever and can’t remember the last time I heard it on the radio. I know Rhyner likes music documentaries, so I tell him about Pearl Jam Twenty, the 2011 film the director Cameron Crowe made for the band’s 20th anniversary.

One element of the film that has stuck with me, I tell him, is when Stone Gossard talks about Pearl Jam becoming singer Eddie Vedder’s band. Gossard isn’t mad about it, exactly, but there is a kind of sadness to him. He started the group, it was his, he wrote the songs, was the driving creative force. And then Vedder joined and took it over. Pearl Jam became a success, but it wasn’t his band anymore, wasn’t the band he’d started or thought it would be, and it’s obvious he has mixed feelings about it all.

Rhyner listens, is quiet for a moment, then says he can relate. “I had that same dynamic with The Ticket, to a very small degree,” he says. “In the early days, that thing was my baby. I set the tone. I brought the guys on board and every—that place was honored for a really long time.” When did it change? “Probably when Cumulus bought it.” This was in 2006. “Which, I knew it would.” A pause. “But I can’t say I was ever totally cool with it. I mean, I went along, because I realized what I had. And, by then, no matter what, I had made my mark. My fingerprints were all over it. So I wasn’t going to make any waves out of it or anything like that. But that dynamic was in play.”

He has been retired for almost two months now, but it is still hard to separate Rhyner from The Ticket, and it probably always will be. He was at Ticketstock—the station’s annual celebration of itself—over the weekend, joining the crew for a roundtable discussion and performing with the house band, The Ticket Time Wasters, including a very good and completely straight take on Post Malone’s “Better Now.” (It’s tempting to read a little into the choice, with lyrics like “You probably think that you are better now, better now/You only say that ’cause I’m not around, not around,” but he just likes the song.)

That will probably be the last time listeners hear Rhyner on The Ticket for a while—and probably anywhere else—as he figures out what, if anything, he wants to do next. As he put it in the video, if something comes along, great. If not, that’s OK, too. When we first met for this story, a few days after he made the announcement, he was excited about the possibilities of an empty calendar. Now, he seems content with the emptiness.

And maybe it’s better that way. Maybe it’s better if he has to just sit for a moment and think about how he wants to answer the question.

What else?