When the squad cars pulled up to the Townes of Highland Park before daybreak, most residents were still asleep. A damp fog hung over the private drive that runs through the gated community of $800,000 townhomes off Lomo Alto Drive. A small army of law enforcement personnel took position: Dallas Police officers, FBI agents, and DEA investigators in black jackets with yellow letters across the back. A U.S. Marshals team wearing tactical vests and helmets fell into a phalanx and made its way toward unit 4205.

Unit 4205 had been under surveillance for months. Its occupant was a 50-year-old man named Gary Collin Bussell, whom neighbors had begun to regard as a nuisance. He was aggressive at community meetings and threw loud parties in the common areas. They watched strange characters coming and going from his townhome at all hours, often carrying thick manila envelopes or brown paper bags. His guests monopolized the few visitor parking spots and had the access code for a back gate that led to the parking lot of an adjacent Whole Foods. A few months earlier, the DEA, FBI, and Dallas Police had executed a search warrant at Bussell’s townhome, hauling off two Glock handguns, a shotgun, and evidence that he used the residence to store tens of thousands of dollars in real and counterfeit cash and counterfeit prescription pills.

Investigators had come to believe that Bussell was the linchpin of a drug trafficking operation. Now, on October 30, 2019, U.S. Marshals moved in to make the arrest. They pounded on the front door, and Bussell calmly answered it. He had slicked-back blond hair and a thin goatee, wearing jeans and a hoodie that covered his tattooed arms. He already had his sneakers on, as if he had been waiting for the officers to arrive. Bussell’s girlfriend, Lisa Young, a 32-year-old blonde, also seemed ready for her arrest. Bussell politely invited the armed officers into his home. His teenage daughter looked on as the U.S. Marshals arrested her father and Young. Then, as investigators combed the townhome, Bussell’s daughter headed to class at Highland Park High School. One officer told me, “It was like she couldn’t have cared less.”

Bussell’s arrest was just one in a string of related busts that day. With him in custody, U.S. Marshals headed a couple of miles away to a house on Stanford Avenue, in University Park, where they nabbed Gina Corwin, a 51-year-old mother of 10. She, too, didn’t seem surprised that cops were at her door. Corwin was involved with the Highland Park community, known for volunteering for organizations that help kids with special needs. One of her sons was a captain of the state championship-winning football team and went on to play at the University of Oklahoma. Officers arrested another atypical drug trafficking suspect, Frank Eric Dockery, a former Plano SWAT sniper and father of two whose wife is a kindergarten teacher. Eventually, 11 people were arrested and charged. The criminal conspiracy began to look like a drug ring of suburban moms and dads.

The charges filed in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas allege that Bussell and his organization sold at least 6 kilograms of the synthetic opioid fentanyl and 5.7 kilograms of methamphetamine over an 18-month period. Officials also claim they have evidence that Bussell was selling marijuana by the pound, prescription opioids, and other substances. But the indictment focused on fentanyl because prosecutors claim that drug was responsible for at least two overdose deaths. D Magazine’s investigation also found that drugs linked to the Bussell organization played a role in the shooting death of a Highland Park teenager.

How did these seemingly straitlaced people get caught up in such a massive drug operation? Since the arrests last year, lawyers, family, and friends of the 11 defendants, who prosecutors allege were part of what they have dubbed the Bussell Drug Trafficking Organization, have all kept quiet. The final pretrial conference is set for May, and sources close to the proceedings say most of the defendants are cooperating with investigators and working on plea deals. It is not clear if the trial will move forward or if the government’s evidence will be made public. The DEA and other agencies involved in the investigation won’t speak directly about the case because they are continuing to investigate additional drug suppliers and distributors connected to the Bussell ring.

But transcripts of preliminary detention hearings, documents filed with the Eastern District of Texas, and conversations with dozens of associates and neighbors—almost all of whom asked to remain anonymous—reveal the extent of the network and the motives that drove these individuals toward crime. It all points to fentanyl, an opioid washing over North Texas.

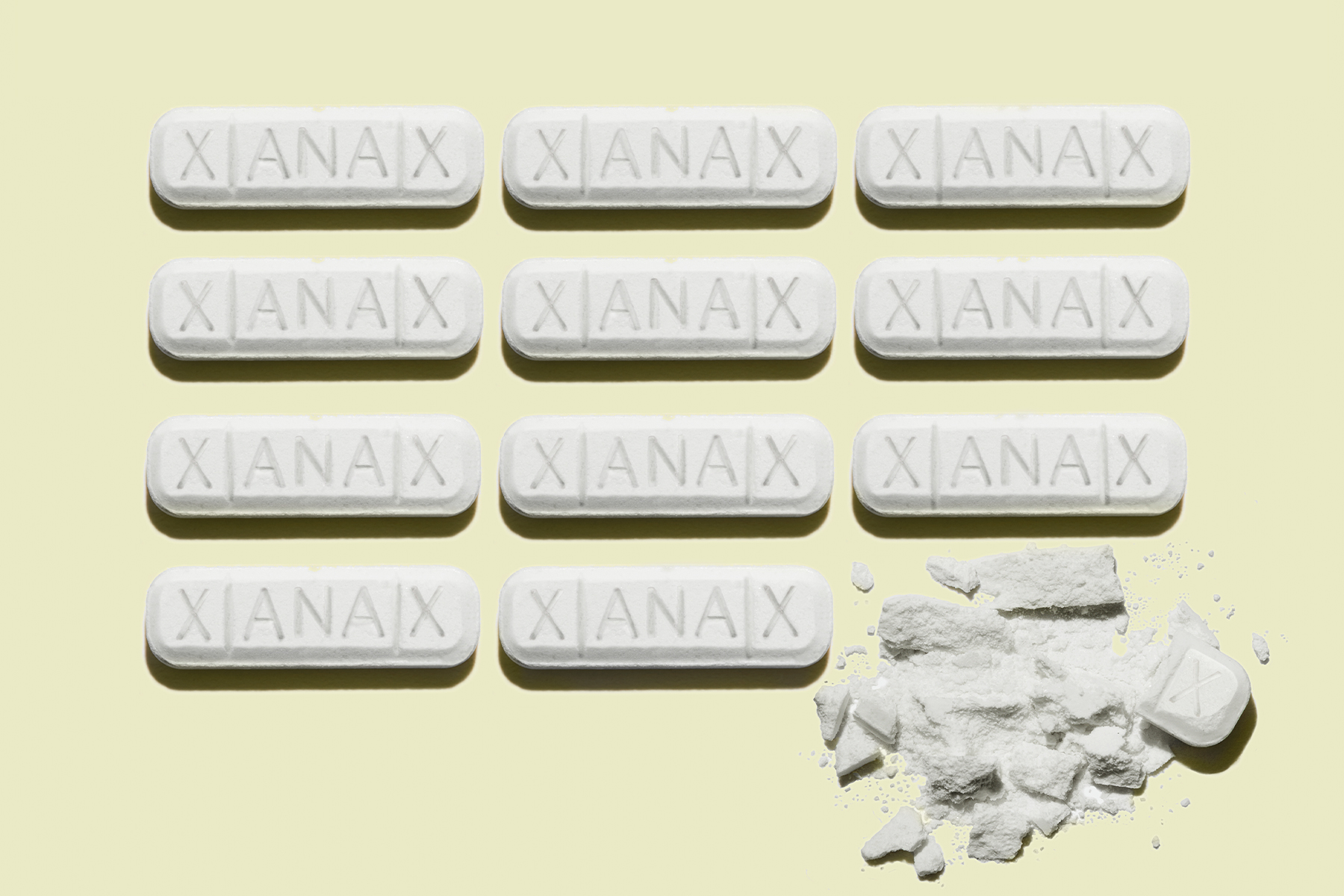

Fentanyl is 30 to 50 times more powerful than heroin and 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine. It is prescribed for extreme pain, often after surgery or for cancer patients, but it hits the streets in the form of counterfeit oxycodone, hydrocodone, and other prescription drugs. Fentanyl is much more potent than these pills, and even small miscalculations in the quantities of fentanyl used to make the fake prescription opioids can prove deadly. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s most recent data, fentanyl is responsible for a 47 percent increase in overdose deaths, from 19,413 in 2016 to 28,466 in 2017.

Fentanyl is the drug that killed Prince, Tom Petty, and Los Angeles Angels pitcher Tyler Skaggs, who was found dead in a Southlake hotel room ahead of a game with the Texas Rangers in August 2019. The reason for its spread is simple: fentanyl is cheap, powerful, and, in certain parts of the country, easy to get. “A kilo of pure fentanyl is going to go a very long way compared to its equivalent kilo of meth or cocaine,” says Eduardo Chávez, special agent in charge of the DEA’s Dallas Division.

But unlike meth or cocaine, fentanyl is sold in the form of knockoff prescriptions that carry few social taboos and have become increasingly mainstream. That has also led to another parallel evolution in the opioid epidemic: the normalization of drug dealers. Aaron Shamo might be the poster child. A 26-year-old Eagle Scout and college dropout from Utah, Shamo called himself a “white-collar drug dealer.” He bought pure powdered fentanyl from a lab in China, pressed the substance into pills in his basement, and found buyers for his product across the U.S. by advertising on the dark web. Shamo sold more than a half-million pills over one year, and when federal agents raided his apartment in 2016, they found $1.2 million in cash stuffed in a sock drawer and a safe. Shamo became a drug kingpin without ever leaving his house.

This may begin to explain how Gina Corwin, the mother of 10, got wrapped up in an organization that trafficked in tens of thousands of counterfeit pills containing fentanyl and methamphetamine. Corwin was born into privilege, the daughter of Jimmy Bishop, an entrepreneur who built one of the world’s largest independent distributors of remanufactured automotive components. He was a member of the Oak Cliff Country Club, and he spoiled the women in his life. Bishop built a house for his wife on Beverly Drive and gave Corwin a Porsche to drive to college at Texas Tech. When he died, in 2010, his estate was split between Corwin and her brother.

The Corwins live in a house in University Park, which, since at least 1999, was owned by a trust in Gina’s name. She married her husband, Mike, in November 1995, and their eldest child was born eight months later. Nine more children followed. Today, the house on Stanford Avenue looks a little out of place on a block that is transitioning to stately contemporary homes. It has a well-worn look that one might expect from a large and rambunctious family. The lawn has been replaced with AstroTurf. There is a large trampoline in the front yard, and a swing hangs from a tree branch. The front porch is given over to wooden lockers overflowing with sports equipment. A succession of Highland Park football stars has run the yard, including Finn Corwin, the son who now plays for the University of Oklahoma.

Fentanyl is the drug that killed Prince, Tom Petty, and Los Angeles Angels pitcher Tyler Skaggs, who was found dead in a Southlake hotel room ahead of a game with the Texas Rangers in August 2019.

Many of the Corwins’ neighbors said they don’t know the family well. They kept to themselves, one said. Sweet kids and a friendly father, another said, but a mother who was a little aloof. One complained that Gina never waved. From afar, neighbors observed the kind of managed chaos that one might expect of a family of 12. One neighbor who lives next door to the Corwins remembers multiple times when he saw Gina rush into her house with groceries, forgetting to close her car door and leaving bags of groceries on the street overnight.

There are rumors and gossip, of course, the whispers that fly around a cloistered, affluent community. But during the weeks after the arrest, friends and neighbors rallied to support the Corwins, setting up a schedule to cook and deliver meals to the family. There is some suggestion that Gina saw trouble coming. Tax records show that in August 2019, as the investigation into the Bussell network intensified, the ownership of the house on Stanford was transferred out of the trust’s name and to a limited liability company with an address in Dripping Springs, Texas. In 2019, Gina’s name was also removed from properties she inherited with her brother, according to Dallas County tax records.

After her arrest, Gina waived her right to a detention hearing, so, unlike the other defendants, evidence has not been made public about her role in the conspiracy. According to a law enforcement official close to the case, the charges are more substantial than just possession and definitely involve being part of the distribution network. The evidence against other defendants that has been made public, however, suggests a pattern. They were a motley crew, from divergent walks of life, but many were users who sold drugs to help fund their habit.

Frank Dockery was a SWAT sniper with the Plano Police Department whom other members of the force called “Doc.” He was well liked, gregarious, and generous—a cop’s cop. If officers needed backup or help with an investigation, Doc would drop what he was doing and chip in. Doc married a kindergarten teacher, had two daughters, and lived a few miles from his parents. But after he was injured on the job, a doctor prescribed him painkillers, and he couldn’t quit them. Plano PD removed Doc from the SWAT team. He entered rehab. When he got out, his job was waiting for him, but so was his habit.

Doc began looking for ways to find the pills he needed. By 2018, he had fallen in with Bussell and his crew. Text messages presented at his detention hearing suggest that Doc saw Bussell and his associates not as drug dealers, but as friends. Sometimes, Doc purchased pills with Ben Westin, a 28-year-old salesman for a high-end cosmetics packaging distributor and an avid skydiver.

“I’m about to leave town with kids and don’t want to run out this weekend,” Doc texted Westin on one occasion.

Westin told him he could scrounge up 15 pills. Sometimes, Doc hooked Westin up.

“Hey if you need one to hold you over, let me know,” Doc texted Westin.

“I do, I’m dying,” Westin replied. The two then agreed to meet near an East Plano police substation to make the exchange.

Text messages cited in court also suggest that Doc and his wife socialized with Bussell on occasion. Doc invited members of the crew to participate in a concealed carry licensing course he ran at the Trenton Church of Christ and a gun range in Greenville. He offered Bussell assistance in beating a urinalysis test. A picture forms in the government’s evidence of a man whose habit began to shape his social universe and who had lost sight of the legal implications of his actions in the process. The help Doc offered his “brother” Westin was, in the eyes of federal law, aiding and abetting with the intent to distribute narcotics. Doc’s weekend firearms classes, a typical way some SWAT officers pick up extra cash, contributed to him being charged with knowingly possessing a firearm in furtherance of a drug trafficking crime.

When he started to associate with Bussell, Doc was on the periphery of a much larger drug distribution network. Bussell ran an efficient and lucrative business. He had multiple distribution points, including his townhome and a duplex on Gilbert Avenue, on the edge of Highland Park. Austin Seymour, a 24-year-old Ohio native, worked out of the duplex as a delivery boy for Bussell. Bussell’s girlfriend, Young, also ran errands for the organization, and he asked her to create inventories of their stock of real and fake prescription pills, marijuana, THC cartridges, and other drugs. They sometimes did business out of the Barley House, a bar a few blocks from SMU. There, Bussell would meet with Seymour and William Grant Allbrook, a 32-year-old co-founder of a real estate investment company who, according to the government’s evidence, provided Bussell’s network with large quantities of counterfeit prescription pills.

Bussell and Seymour were regulars at the bar. Bussell drank Maker’s and Sprite, and bartenders knew him well enough to mix the drink when he pushed through the door. He took his daughter out to eat at the Barley House after school. Regulars recall Bussell having bags of THC-infused gummies on him. According to court documents, investigators observed Bussell meeting Todd Shewmake, one of the co-defendants, at the Barley House to sell him 100 bars of Xanax. Most patrons and staff turned a blind eye to the animated and eccentric Bussell, figuring it was best not to know too much about what he did for a living.

For a long time, business was good. Over an 18-month period leading up to their arrests, Bussell’s organization moved at least 54,000 fake oxycodone pills and 18,000 fake Adderall pills. They had no problem finding customers. Bussell was selling weed and pills in the heart of a community that was hungry for both. He was connected to Dallas’ art, fashion, and restaurant worlds, and he had children in the Highland Park school system. Bussell offered a convenient hookup. One Highland Park mom I talked to bought some pot brownies before a weekend girls getaway and met Bussell in a parking lot a few blocks from her house. Another met Bussell with a friend at an apartment and was surprised when he invited her in to hang out for a while. An owner of a local restaurant traded meals for pills. Customers say Bussell could be jittery and hyper but also friendly and low-key. “He asked me if I ever wanted to, you know, give him a call,” said one general manager of a Dallas restaurant. “I knew he dabbled in some stuff and thought it was just the normal Dallas scene. I thought he had a normal job.”

Bussell talked about his dealers as if they were his employees. Joey Pintucci, a teenager at Highland Park High School and friends with Bussell’s daughter, may have been one of them. Pintucci had a difficult childhood. His mother was an addict, and she died when he was 7 years old. His father was not in the picture, and his aunt, Andrea Haag, became his guardian. Pintucci was a smart kid, but his ADHD sometimes made school difficult for him. At first, Haag moved in with her parents so she could afford to send him to private school. Then she moved the family to Highland Park. “We were apartment dwellers at first,” Haag says. “We were on the outskirts, but we were accepted, initially.”

Friends describe Pintucci as rebellious but popular. Haag says he had a big heart but also got into trouble. “He did things to make himself sound cool,” she says. Pintucci became friends with Bussell’s daughter in middle school, and they would sometimes hang out at her father’s house. Haag heard gossip about Bussell. “I was definitely warned years ago to keep my child away from him,” she says. “Other parents were like, ‘Hey, this is what’s going on with that family, and you want to keep away from them.’ ”

In high school, Pintucci played football, but when his grades began to slip, he was kicked off the team and found himself with too much time on his hands. “It was really frustrating,” Haag says. “He really needed those male role models. When he met the Bussell family, he was a very young teenager. A very young, impressionable teenager.”

Haag doesn’t know if Bussell recruited Pintucci to deal drugs, but at some point her adopted son started to deal. In March 2018, Haag withdrew him from Highland Park and enrolled him in Evolution Academy in Richardson, which she hoped would be better suited to handle Pintucci’s learning differences.

Court documents indicate that Bussell associated with people who investigators suspect sold marijuana, edibles, THC canisters for vape pens, cocaine, and mushrooms. But the charges he and the other defendants face focus on fentanyl—the counterfeit pills. According to Special Agent Chávez, manufacturers are becoming increasingly sophisticated in replicating the real thing. “It [used to be] almost comical,” Chávez says. “The color of green was off, and the OC-30 on it was just a little crooked on some pills, and you take it and kind of press it and it would crumble. They hadn’t figured out the binding just yet. Now you look at them and you put them side by side, and, unfortunately, it almost takes a chemical analysis to be able to tell the difference.”

I spoke to one Highland Park woman who, with a friend, bought what they thought was Xanax from Bussell. When her friend popped a pill on a Saturday, she fell asleep and didn’t wake up for 24 hours. When she regained consciousness, she called Bussell and asked him what was in the pill he’d sold her. He apologized and said he’d forgotten to tell her that it contained fentanyl. Court documents indicate Bussell was confronted by multiple individuals who had suffered nonlethal overdoses from pills they’d bought from him. According to one person quoted by investigators, Bussell was dismissive about the risky pills. “You bought them, you own them,” he said.

Ryan Pearson was 29 and grew up in El Segundo, California. His father died when he was young, and his family later relocated to North Texas. Pearson loved video games, animals, and his family. His Facebook page is filled with pictures of dogs and cats, a turtle and a frog, graffiti murals, and him holding his newborn niece. In 2015, he posted about his second anniversary of sobriety. But by 2018, he had relapsed. Around 3:30 pm December 27, Pearson texted his friend Scott Perras, who sent him Westin’s phone number. It is not clear from the government’s evidence how the rest of the evening unfolded, but what we do know is that after he was contacted by Pearson, Westin texted Doc, the Plano cop. They agreed to meet with Bussell. Afterward, Pearson met Westin, who sold him a pill that Pearson believed was oxycodone. That night, Pearson was playing video games in his apartment in Fairview when he took that pill. Sometime after midnight, Pearson’s girlfriend found him. She couldn’t wake him. She called 911 and the Fairview Police arrived at 12:42. Pearson had died of a fentanyl overdose.

In the emotional fog of the moment, Pearson’s girlfriend began searching through his phone. She found a number she didn’t recognize, and when she called it, Westin answered. The two would exchange several calls and texts over the next few days. Westin struggled to figure out what to do. He called Doc. According to testimony by Dallas Police Detective David Roach, who was called in by Fairview Police to help with the investigation into Pearson’s death, Doc tried to assure Westin that his exposure was limited. Westin sent Pearson’s address, and Doc ran it through the Plano PD’s database. “Nothing came up,” he texted. They appeared to be in the clear.

But a month later, Bussell’s daughter was involved in a drug deal that would generate headlines. In January, Pintucci arranged on Snapchat to sell THC canisters to a few of his classmates from Evolution. They planned to meet at the Shops at Park Lane, on Central Expressway, across from NorthPark. Pintucci parked his white 2002 Lincoln sedan in the empty parking garage in front of Dick’s Sporting Goods. Bussell’s daughter and another friend were in the back seat of the car. A little after 10 pm, three men approached the car in single file and pulled out handguns. They forced Pintucci to hand over the drugs. As they ran from the car laughing, one man fired into the car, hitting Pintucci. He was taken to a hospital, where he later died.

The students at Highland Park High School were devastated by the news of Pintucci’s killing. Even though he no longer attended the school, a spot on the senior wall was transformed into a memorial, where they scribbled messages like “rest easy homie” and “the king.” The Dallas Police Department’s investigation into the murder focused on the three suspects, and 10 months later, Snapchat messages would lead to the arrest of 19-year-old Juan Cardenas, one of Pintucci’s classmates at Evolution, who has been charged with capital murder.

Investigators observed Bussell meeting Shewmake at the Barley House to sell him 100 bars of Xanax. Most patrons and staff turned a blind eye to the animated and eccentric Bussell.

The DPD investigation did not focus on the source of the drugs that Pintucci was selling that January night. An investigator working the case told me that the THC canisters looked store-bought, like the kind that are legal in Colorado and other states, and they didn’t pursue their origin. The fact that Bussell’s daughter was in the back seat of the car that night, however, was raised by a prosecutor during Bussell’s detention hearing. Detective Roach testified that Bussell’s daughter got the drugs from her father, possibly without his knowledge. “And during the course of that narcotics transaction, another individual engaging in that transaction with her was ultimately shot and killed during that transaction,” Roach told the court.

The investigation into Pearson’s overdose death began to peel back the layers of the Bussell network. Even though Doc assured Westin that he couldn’t find anything about Pearson in the Plano PD’s system, the death had triggered an investigation that quickly escalated into a multiagency effort. The Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force was established in 1982 to disrupt operations with criminal activity stretching into multiple jurisdictions. It includes investigators with the DEA, FBI, IRS, U.S. Postal Service, and members of a number of local police departments.

Through a search of Pearson’s phone, investigators knew Pearson had purchased the fake oxycodone pill from Westin. In March 2019, agents served a warrant on Westin’s apartment. They found two firearms; fake oxycodone and real alprazolam pills containing fentanyl; cocaine; marijuana; pure THC extraction; and a large quantity of mushrooms. After the search, the investigation appeared to go quiet. No charges were brought against Westin, and no additional searches were conducted. During this time, prosecutors say, Doc used his access at Plano PD to keep tabs on the ongoing investigation. Roach testified that Westin continued to sell and use counterfeit pills after Pearson’s death. “It appeared that when he got money to buy pills, he would do some and then sell some,” Roach said. “And then the cycle would repeat.”

Throughout that summer, investigators traced the origins of Westin’s pills back to Bussell and into a larger, more complex network. They uncovered an operation with multiple wholesale sources and a loose network of user-dealers scattered throughout North Texas. One of the main sources of counterfeit pills was a Houston pill press that also figured into a separate ongoing DEA investigation. A 36-year-old Garland resident named Peter Yin was suspected of supplying pills to the network, as well as distributing pills to networks in Virginia and Ohio. Bussell and Allbrook were dealing with huge quantities of cash, sending tens of thousands of dollars through the U.S. Postal Service, some of it counterfeit, and operating money laundering operations that processed upwards of $100,000 per transaction.

That same summer, the organization ran into some friction. About every two weeks, Bussell and Allbrook sent shipments of cash, $80,000 bundles wrapped in duct tape, to various suppliers. After one shipment, Allbrook alerted Bussell to the fact that they had sent some counterfeit bills. “It was just 200, thank goodness,” Allbrook told Bussell. “Just need to keep our eyes peeled. I don’t want to end up with a stack of those.”

The managers were also having trouble with Seymour, the duplex delivery boy. “Austin’s stressing me out this week,” Bussell told Allbrook. “He may be unemployed by the time you get home. Sorry my partner, this is our business not his.”

In August 2019, agents finally executed search warrants on Bussell’s Highland Park townhome and the duplex on Gilbert. After the raid, investigators testified that Bussell called a meeting at the Gilbert house, where he and members of his network discussed fleeing the country. Bussell offered to purchase a copy of a Social Security card and birth certificate and head to a non-extradition country. Investigators estimated that based on the quantity of pills and marijuana, the amount of cash they seized, and their knowledge of offshore accounts, they had more than enough resources to skip the country.

But no one left. By this point, Doc had worked his way closer into the organization’s inner circle. After the raid on Bussell’s properties, he couldn’t understand why so much time had passed between the March search of Westin’s apartment and the August raids. But he wanted to assure his friend that, no matter what happened, he would be there for him. “Just going to say I ain’t going to distance myself, bro,” Doc wrote to Bussell. “You’re my friend. Laying here running shit through my head trying to figure out what I can come up with to help. Just wish I knew what they knew. Just weird how they took so long to come. Anyhow, try and relax and enjoy your trip no matter what.”

On October 30, the hammer fell. The task force rounded up 10 individuals associated with the Bussell organization and charged them with multiple counts related to drug trafficking, weapons possession, and providing the drugs that led to Ryan Pearson’s death. Some of the charges carry minimum sentences of 20 years. About a month later, Peter Yin was also taken into custody. Bussell, Westin, Perras, and Yin were all charged with directly supplying the drugs that led to Pearson’s death. Doc faced charges for possessing and providing firearms in furtherance of a drug trafficking crime as well as interfering with the investigation of Westin’s alleged crimes. Gina Corwin was charged with two counts related to the knowing possession and distribution of substances that contained fentanyl and methamphetamine.

During the detention hearings, each of the defendants’ lawyers presented evidence and witnesses in an attempt to show that their clients were not the notorious drug dealers that prosecutors made them out to be. The testimonies highlighted one of the stranger elements of the case, that the drug distribution network was made up of a ragtag crew of people who lived double lives.

William Grant Allbrook’s sister died in a DWI crash when she was 24 years old. He ran an annual golf fundraiser for a charity he founded in her name to help underprivileged kids take dance lessons. After Peter Yin’s mother died, he took care of his elderly father and was described by friends and family as the glue that held his family together. Scott Perras’ stepdaughter told the judge in a letter that he picked her up from school every day and played video games with her. Frank Dockery’s wife, Jaime, said her husband was taking medication to help with his opioid addiction and that he loved his two little girls, missed them terribly, and wanted to be home with his family.

Only one of the defendants—Perras—managed to secure pretrial release. The experience of Gina Corwin’s co-defendants may suggest why she waived her right to a detention hearing. It is difficult to secure pretrial release when facing federal felony drug charges, and by waiving her hearing, Gina saved her family the humiliation of dragging the allegations against her into the public record. Defendants sometimes waive detention hearings if they plan to make a plea deal. A quiet plea deal may keep some details of her alleged crimes from her neighbors. Which leaves the strangest question in the case unanswered. How did a University Park mother of 10 fall into such a mess?

It is one of many questions that may never be answered if the case doesn’t go to trial. How was Bussell able to launder so much money, and how did his organization’s activities connect with other trafficking networks? According to court documents, Bussell conspired with an unnamed individual in Dallas to launder money through personal and family business accounts. Other witnesses testified to investigators that Bussell arranged with co-conspirators outside the United States to launder income from drug proceedings. Another accusation made by investigators suggests that a member of the Bussell organization received bulk shipments of counterfeit Adderall pills containing methamphetamine, and this individual sent those pills to someone for distribution on a college campus.

There are many such connections between the Bussell organization and operations in Seattle, Houston, and elsewhere. Digging into each begins to feel less like investigating a criminal network and more like tracking the spread of a virus. For years, Bussell and his colleagues sold tens of thousands of potentially lethal pills, and there is no telling how many are still out there. Days before the second detention hearing, investigators said they learned of a second overdose death that could be tied to the Bussell network.

At one of the detention hearings, Tina Pinotti, Ryan Pearson’s mother, sat in the courtroom. Although the family declined to talk about the case, Pinotti posted on Facebook her reaction to the arrests. “While this does not bring our beautiful boy back, Ryan and our family will receive some justice,” she wrote. “Many, many families are not as fortunate, and no one is ever held accountable for the death of their loved one. I find some peace in knowing that these people have been taken off of the streets.”

But the pills are still out there. In medicine cabinets from the Park Cities to Seattle, fentanyl is hiding in what people think is Xanax or oxycodone. For those people, justice might be hard to find.