Maclura Pomifera

by Joe Milazzo

The first time it happens, you’re doing 85 down that stretch of 30 where every other billboard is for an ambulance chaser or a casino.

Four in the morning or thereabouts; of course, you’re fried. At the distribution center, yours is manual labor, not altogether physical—dishonest, sort of. You reckon it suits you. Yet you can tell your nights there are already numbered. It’s when you’re making a point of not obsessing over the inevitable that the ancient pickup nearly plows into your lane.

You wrench toward the shoulder, rage rising in your throat, brakes griping. In the rust bucket’s bed, hardly muffled by the plastic blue flap of tarp, an impossible green screeches. Not parrot; not exactly Martian either. A toxic-ooze, laundry-detergent-aisle, live-wire green. But—and maybe it’s just your adrenaline draining—you know those associations don’t radiate quite right.

You’re late on your horn. The relic and its pilot have sped away, trailing black exhaust and busted taillights. You don’t remember flipping on your hazards, aggravating their arthritic “tock, tock, tock, tock.”

What you wouldn’t give if, just once, they ticked.

•

By the time of your second encounter, you’ve hooked up with the backpack vacuum cleaner crew at a 24-hour data center in Farmers Branch. This is your new commute: intersections timing out to the rhythm of blinking yellows. As always, you’re headed south. The little Fiat is heading east, its back seat and cargo area on fire with the color.

Your lips feel spicy. You pursue, fully aware that you’ve got no clue how pursuit is supposed to work. A red light finally cooperates. You inch up in tailgating position. You want to spit but you wipe instead, the air conditioning too precious to make lowering your window worth it. The driver is obscured by the car’s freaky payload, but you can almost recognize the spacing between the bass notes of whatever’s blasting on its stereo.

The green is a mass of masses—tumors, growths, an embarrassment of them, crawling with bulges and veins. Each specimen is about as big as a tennis ball, or a mutant grapefruit. That’s it. You wipe your mouth. An arm, sleeved in denim, emerges from the Fiat. You know this fruit. You’ve hefted your share before, handled how heavy its yield is for its size. You’ve scored bull’s-eyes—falling fence, neighborhood watch warning sign, cousin—with its thudding uselessness.

But this harvest must have some value, enough to be muled around in the dead of night. The driver’s hand is gloved. No, even as contraband, this plentifulness lays up no sugar, no stickiness, no smacking appetite in your imagination. Only globby omens of August.

The driver makes a fist, unmakes it. How is it you can see something like you’ve never seen before when you’ve been looking at it your whole life? You wipe your mouth again, smearing your chin with flowery aphasia.

You’ve been bumper-to-bumper too long. Now the driver is waving, giving the universal signal to go around. You do as commanded, punching it, zipping up to the next break in the traffic island. You execute an impressively illegal U-turn. The Fiat is long gone, having left you to face the stark prospect of retracing your steps.

•

You take another graveyard shift. Your new employer prints funeral programs and only funeral programs. Bad news: tonight you overloaded the pallet jack, upsetting dozens of boxes. Good news: nobody else witnessed the spill of high-gloss faces—the woman with the wolfish eyes and Coke-can-red wig, the newborn with the toothless laugh, the uniformed cop, the eventual broken neck in the starched pearl-snap blinged with horseshoe collar tips.

Again, a truck. An F-150, white as toothpaste. You’re about to pull away from the QuikTrip when it rumbles over to the free air station. Heaped in the back, that green, naked now, jostles all over itself. You kill your headlights and slip from the pump. A yellow diamond promises that your parking spot is a SAFE PLACE, the A in PLACE storied like a tiny house. You pitch your side-view mirror, nearly periscoping it, watch to see who or what emerges from the truck. But there’s no movement, unless you count the insomnia that’s pretending to do your thinking for you.

Does it surprise you that devouring is the antidote to being devoured? It’s not that you covet the green’s flesh; rather, its name, or whatever secret thorniness is glitching your memory raw. Your mouth is dry. That this fruit is inedible is no temptation. That it might be poison is. You picture your teeth breaking its density, rind to core. You will let its sap soak you with its worst. You will let its geography suffocate you. You will salvage the seeds, scatter them, tend to the branching and canopying overloaded inside them, keeping them earthbound—a tending you can repeat.

You unlock your phone. You have 63 LinkedIn notifications, 427 unread emails. You start texting yourself: SQUARE THE SPIRAL. You backspace over that, tap out JUST STOP IT, give that message the thumbs-up. You unclick your seatbelt. You are going to cross the concrete and ask the driver of that truck, straight up: “What’s it called?” Failing that, you’ll plead out, concede to the relief of admitting what’s been weighing on the tip of your tongue.

You wobble at first, settling into your intent as you wade through the last ebb of yesterday’s heat. Approaching, the finer details of your private hell start to bleed, losing their resolution. It has to be the same truck. It sports the same monster Bridgestones, the same windows tinted to ticketable excess. But the bed, the same one, is barren. Above the evidence of the green’s ghosting, on the same back windshield, a rectangle you’re positive wasn’t plastered there before flares its orange. It swears to the truck’s abandonment—and yours, too.

Joe Milazzo is the author of the novel Crepuscule W/ Nellie and two collections of poetry: The Habiliments and Of All Places in This Place of All Places. He is an associate editor for Southwest Review, a contributing editor at Entropy, and the proprietor of Imipolex Press. He lives and works in Dallas, where he was born and raised.

Beatrice

by Harry Hunsicker

Beatrice preferred the company of the dead to the living.

The living held no interest for her, their existence nothing but noise, this movie or that TV show. Whatever nonsense they’d seen on their cellphones.

The dead were on the other side. They could answer her questions.

Hector, the man from the county, sat on the divan in Beatrice’s living room, the one upholstered in crushed velvet that used to be red but was now faded pink.

Beatrice and her husband had bought the piece of furniture at Sanger-Harris in 1965. They had taken in a matinee, Dr. Zhivago, at the Majestic. Afterward, they had gone shopping. She remembered that day like it was last week.

Hector put his cup and saucer on the coffee table, centering them on a doily.

“Would you care for more tea?” Beatrice asked, even though it looked like he hadn’t taken a sip of what she’d poured for him.

“Thank you, no.” He picked up his clipboard. “Tell me about your family.”

Beatrice’s house sat across the street from the only cemetery in University Park, a quiet little town surrounded by Dallas.

She looked out the window at all the graves and sighed.

Hector said, “Doyle? That’s your husband?”

Every day about this time, she liked to wander through the tombstones. Just to listen.

“Was,” she said. “He’s gone now.”

Hector looked up from his clipboard.

“We built this home. Doyle and I did. 1962. We were newlyweds.”

The house had been the biggest on the block at the time. Three bedrooms, a two-car garage. A basement, too—one of the few in the city. Now it was the smallest home for miles around.

“Have you had someone look at the roof?” Hector pointed to the damp spot on the carpet.

Beatrice didn’t speak.

He jotted something down. “And no children, right?”

“Jenny. Except for her.”

Hector tapped his pen on the clipboard.

“Our only child,” Beatrice said. “She died when she was a toddler.”

The pain from Jenny’s passing was a constant in Beatrice’s life, a hole in the middle of her chest, the jagged edges worn smooth by the passage of time.

Such an angel, skin like alabaster, flaxen hair. Beatrice remembered their last night together, how beautiful Jenny had been in her tiny gown and robe, cheeks red with undertaker’s rouge.

Doyle hadn’t wanted the child to sleep in the bed with the two of them, but Beatrice had insisted. It was the night before they put Jenny in the earth. How could she not be with her parents? So the child lay between the two of them, cold and still, until it was time for the funeral.

“Do you have any problems living alone?” Hector asked.

Beatrice pushed Jenny from her thoughts and stood. She shuffled to the window and stared at the gravestones.

“Ma’am? Are you all right?”

“I’m not alone,” Beatrice said.

“The county has people who can help you.” Hector put his pen away. “That’s why I’m here.”

Outside, a gust of wind blew through the live oaks in the cemetery. Leaves skittered down the street.

“I already have people who can help me.” Beatrice turned from the window.

“Could I get a name for the file?”

“Maybe one of them will tell me about Jenny someday,” Beatrice said.

Silence.

She stared at the man. He was in his 40s, with thick black hair and watery brown eyes. He seemed like a nice person. She wished he could understand.

“I don’t see where you have any other family.” He shook his head. “That’s a problem.”Beatrice realized that Hector would never understand.

“The county needs to find a place for you to live,” he said. “It’s for your own good.”

“I don’t want to leave here.” She turned her gaze to the cemetery. “This is my home.”

Hector slid the clipboard into his briefcase. “We’re in between a rock and a hard place here, ma’am. Your house is not habitable. The smell—how long since you’ve taken out the garbage?”

She looked away from the cemetery. “I wish you could have met Jenny.”

Hector smiled. “Me, too, ma’am.”

“Would it be OK if I packed some things? Before you take me to my new place?”

Hector’s brow furrowed. After a moment, he nodded.

“Could you help me get my suitcase?” Beatrice asked. “It’s in the basement.”

•

Beatrice strolled through the cemetery, one hand brushing against the tombstones. She wished for the courage to join her daughter, but she was weak. Always had been, according to Doyle.

The sky darkened as clouds formed overhead. The wind grew strong and cool.

She stopped at Jenny’s grave. “Hector wouldn’t tell me anything.”

Silence.

“Sometimes, when they leave, I can hear things,” Beatrice said. “The newness of it, I guess. They talk to me as they reach the other side.”

Thunder cracked in the distance.

“I ask about you, Jenny. I always do. I just want to know that you’re all right.”

Across the street a sedan stopped in front of Beatrice’s house. The car parked behind the one that Hector had driven. The vehicles were the same make and color. A few seconds later a police car screeched to a halt nearby.

“Why won’t you talk to me, Jenny?” Beatrice knelt by her daughter’s grave, the revolver in her hand.

Doyle had given the gun to her when they moved into the house. For protection, he’d said. A revolver and a candy tin of bullets, 20 total.

Beatrice had 10 left, and she wondered if that would be enough. How many more people would she have to lure to the basement just so she could ask about Jenny?

Across the street, a police officer pointed to the cemetery.

Beatrice pushed herself off the ground and stood. She cocked the hammer of her gun and lumbered toward the home that she and Doyle had built.

Harry Hunsicker is the former executive vice president of the Mystery Writers of America and the author of eight crime thrillers, including Texas Sicario (January 2019) and The Devil’s Country, which is in development as a feature film. He is a fourth-generation native of Dallas, and his fiction has been shortlisted for both the Shamus and International Thriller awards.

Munger

by Will Clarke

The estate sale began at 10, just like the flyers posted at the Lakewood Starbucks had promised. Long folding tables overflowing with Betty Ruth McCormick’s earthly possessions had been set up in the garage of her Munger Avenue home, and people were parking their Toyotas and Hyundais along the curb of the street.

“It’s crazy. You’ll be surprised at what people will pay cash for,” the estate sale coordinator had told Betty Ruth’s son.

This was right before she opened the garage doors and the people rushed the tables. These people scoured Betty Ruth’s personal effects—her girdles, her brassieres, her cookbooks, her Uno cards and her Scrabble tiles, even her false teeth. Her false teeth!

And now these people—the kind of people who spent their Saturdays driving around paying cash for someone else’s false teeth, were walking into Betty Ruth’s house without even knocking on the door. Trying on her wigs. Criticizing her silver patterns. Plugging in her old sewing machine to make sure that it still worked.

“Well, it won’t work if you keep playing with it like that!”

All of this would have been fine. Really. Death had a way of putting things into perspective, and Betty Ruth would have been fine with getting rid of all these useless things. She had been, if anything, a pragmatist.

It was just that no one prepares you for all these people—God, these people—walking around your house with their muddy shoes, acting like you don’t see them. Like you don’t see them rearranging your Hummel figurines into those positions.

“My God. That’s disgusting. Don’t make them do that. Why would you make them do that? What is wrong with you?”

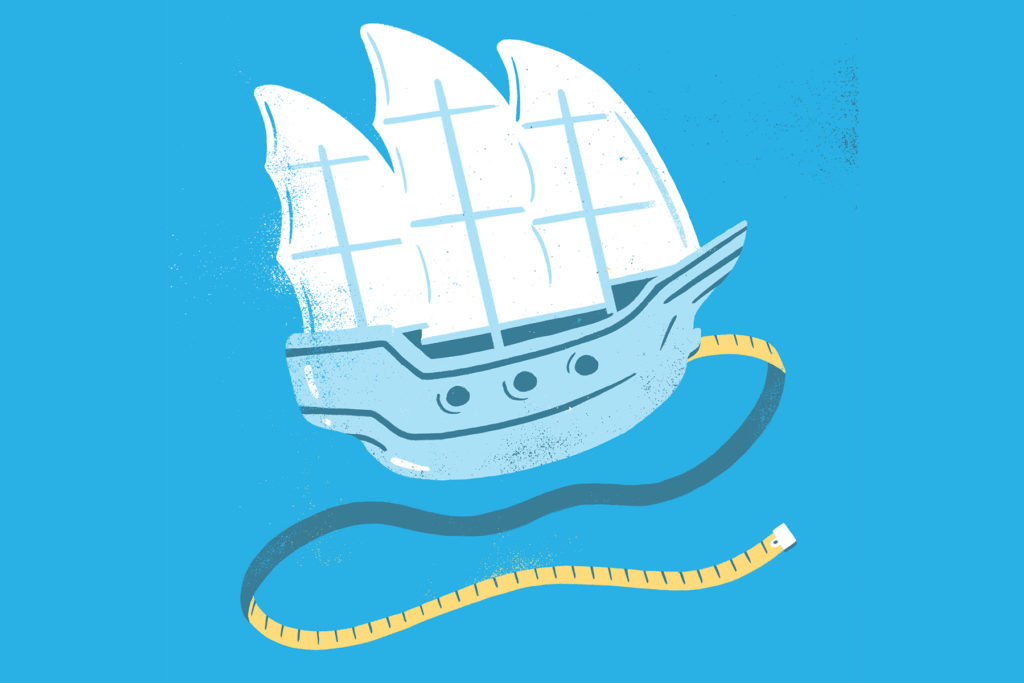

These estate sale people were not good people. No, they most certainly were not. Good people do not walk into a stranger’s house and let their 3-year-olds touch your dinner bell collection. And they definitely don’t bicker with your son over the price of his dead mother’s prized tape measure. Yes, a figural tape measure in the shape of a majestic white sailing ship that Betty Ruth had loved.

“It’s worth more than $5, you snot rag!”

That was, perhaps, the Alzheimer’s. It had made Betty cuss like a sailor. Or maybe it wasn’t the Alzheimer’s. Maybe these people haggling over her beloved tape measure had been the last straw.

Oh, that tape measure. It was her favorite.

For most of her life Betty Ruth McCormick had kept that tape measure like a secret, in the pocket of her sewing apron. She had had a habit of putting her left hand into her pocket and worrying the edges of the ship’s ivory sails, especially when she was trying to figure out how to sew a dress that she had no business trying to sew. The tape measure had been a quiet part of everything that Betty ever made. It had helped Betty Ruth turn McCall patterns into outfits, denim into dungarees, gingham into dresses.

When Betty Ruth was younger, she had considered the tape measure to be a good luck charm; she liked to imagine that the ship would bring her amazing travels. Later, after she’d had her babies, and her marriage to Abe had settled into a dull but steady rhythm, Betty Ruth would dream of sailing away from Dallas as she sewed her daughter’s dance costumes, as she repaired her son’s britches. She would dream of taking a pirate lover, of living on a desert island eating pineapples and coconuts, of diving for pearls with a knife clenched between her teeth.

Betty Ruth had created a whole story between the white sails of this ship, and for a while in her 30s, Betty had wanted to pen a romantic novel based off these voyages—once the kids left the house, of course, and Abe retired.

Oh, this ship-shaped tape measure really was a thing of beauty. It had helped Betty Ruth make so many necessary things. It had helped soothe her worried hands. It had been a simple constant in a life that had quite frankly been too hard. After all, Betty Ruth lost her sweet daughter, Rhonda, to ovarian cancer; then Abe to Parkinson’s; and then, later, the Alzheimer’s hit like a hurricane.

“But that’s life.”

As trite as that saying was, it had comforted Betty Ruth when she said it aloud. After all, no one tells a young bride on her wedding day that she will one day bury her daughter and her husband within a year of each other, and that the world will expect her to just carry on.

So for this very reason, Betty Ruth regretted keeping her ship-shaped tape measure tucked away in her pocket. She should have shared it. Her daughter should have played with it. Her son should have borrowed it. Something this wonderful deserved to have been seen by everyone, displayed in a curio cabinet, or even a museum. For that matter, so did Betty Ruth’s dreams. They had been just as exquisite.

Yes, Betty Ruth had once been brave enough and young enough and dumb enough to have had dreams, and today, she didn’t feel like letting them go—not just yet, not with all these people in her house, not with her son locked away in her pink-tiled bathroom, crying like he was.

Will Clarke holds an M.F.A. in creative writing from the University of British Columbia and lives in East Dallas with his wife and family. He is the author of several works of fiction, including The Neon Palm of Madame Melançon, Lord Vishnu’s Love Handles, and The Worthy: A Ghost’s Story.

The Drip Drip Drip

by Brooks Egerton

They looked like icicles, yessir, they did. hanging from the ceiling in the old police basement, parking garage, whatever you wanna call it. Where they let Ruby shoot Oswald, man! Long time afterward, you could walk down the ramp from Main Street, see a bloodstain if you knew where to look. Now they got it closed off. It was in your newspaper—the stalactites, I mean. I’ve still got a copy somewhere. Hell, I’m the one told y’all about it. Wrote it on a parking ticket I fished out of the trash, carried it over to your old building, dropped it with the front-desk lady. Corner of Houston and Young, ROCK OF TRUTH carved in stone, all capitals, right? TRUTH AND RIGHTEOUSNESS, actually. Folks usually forget the rest of that line. Told y’all it was like a cave, water dripping, always searching for lower ground.

How come I know so much? ’Cause I lived there, man. They didn’t put that in their report, huh? Lived in the men’s room down the hall from Homicide, back when they didn’t have no security and a man could roam. There was a hole in the bathroom wall, nothing covering it except a box of paper towels! I remember the January day I found it and crawled on in. Warm and dry, like my cell here, but free. A good year passed before one of my enemies tried to claim it. You know I had to cut him. Cops didn’t wanna hear that, of course. They made up their mind soon as they heard the hollering, saw his blood searching, doing that drip drip drip.

Brooks Egerton used to be an investigative reporter at the Dallas Morning News. Now he’s working on creative writing projects.

A Common Thing

by Latoya Watkins

Chasity cursed and hit the steering wheel when she realized she’d left the gift bag, balloon bouquet, and card on the kitchen island of her Deep Ellum condo. She was already in Plano. She couldn’t turn around. She had to get to the shower on time. Everyone would be there—Momma, her sister, the aunties, and all of her sister’s friends. She needed to get there to be what they needed her to be. The only one without a man or children. It made them feel useful to tell her why.

You spent too much time trying to be white and done missed being what you ’posed to be, Momma told her at the last event. The time before that, one of the aunties said, Don’t no man want no woman that can’t be on time.

She imagined her family watching the door, waiting for her to arrive with a new handbag or scarf or shoes. And then their smiles at the end of the shower—smiles meant to remind her that no matter how put-together she appeared to be, she’d still go home alone. Smiles meant to remind them of who they were.

She sighed and took the Park exit off the Tollway.

Her family would never understand her experience. That her degrees didn’t get her through tough workdays. It took much more than that to be the only black woman—the only black person—in those spaces. She was constantly fighting for herself—for them—for how people saw them. Yet all her family would see her as was the bourgeois one who blended in.

She was relieved when she saw the Super Target on the service road. She’d have to be practical. She wouldn’t get more cute little outfits. She’d get the ones she’d already purchased from Neiman’s—the ones she left behind—to her sister later.

She drove down a few aisles in the parking lot before she spotted a C-Class Mercedes, almost identical to hers, pulling out from a space near the entrance.

“This day might just save itself,” she said out loud.

She exited the car and looked down at herself. She smiled, pleased at how well the off-white, high-waist slacks fell at her Chanel mules. Her family would know they were Chanel, but they would not know that they were more than three seasons old and that someone else had owned them first.

She let her Birkin bag slide down to the crook of her arm and headed inside. She didn’t worry that people would spot her purse as a fake. Her Asian bag lady was good. For a mere $200, Li’s bags could fool the most trained eyes.

She grabbed one of the red carts from inside the store and headed to the back, toward the baby section. She kept going past the infant and toddler clothing, the strollers, high chairs, and car seats, and smiled when she saw the perfect rows of diapers.

This is it, she whispered. She was well aware that new mothers could never have enough diapers. She began to grab two packages of every size of the natural, eco-friendly brand, until she got to a size that was blocked by a thin blond woman hovering over a cart with a baby carrier attached to it. The woman was holding a bottle to the child’s mouth, and it didn’t appear that she would be moving anytime soon.

“I hate to interrupt,” Chasity said. “I need that size.”

The woman smiled but moved her cart only enough to leave a narrow space between it and the diapers.

“Thank you,” Chasity grunted, squeezing through the narrow space, grabbing the packages, and squeezing back through to her cart.

Moments later, she let out a frustrated sigh. Another cart sat blocking the next size she needed. There was a purse in this one. A large signature Louis Vuitton. But there was no driver attached to the cart.

Chasity looked back at the woman feeding the infant. The woman’s eyes widened, her mouth turned down, and she shrugged her shoulders and pointed to the other end of the aisle. “I think it’s theirs,” she said softly.

Chasity followed the woman’s finger to two white women near the end cap. One appeared to be middle-aged and the other a bit older. They looked like mother and daughter. And as if she could sense Chasity’s eyes on her, the older woman, the mother, looked back at Chasity.

Her white hair was cropped close to her head, and her khakis, polo shirt, and boat shoes told Chasity all she wanted to know about her. Her eyes darted from the purse in the cart to Chasity, and her tiny mouth dropped into an “o.”

“Jenny,” she said, rushing toward the cart. “How many times do I have to tell you about this?”

The daughter looked up from whatever she was examining on the end cap, just as her mother snatched the bag from the cart. Just as Chasity made sure there was enough distance between her and that cart to certify her innocence.

And they all waited. Just stood there, holding their breaths, it seemed, as the mother went through the purse.

Chasity watched the daughter exhale with relief when the mother finally said, “Everything’s here,” shoving the bag in her daughter’s direction.

Chasity cleared her throat and said, “Excuse me,” before pushing the empty cart out of her way and reaching for the diapers. The other women held the quiet. Each avoiding her with their eyes, like she had made them uncomfortable and embarrassed, like a wrong thing—a common thing—had been done to them and all around them but not by them.

Chasity held her head steady and pushed her cart away from the aisle. As she made her way to the front of the store, she looked down at her Chanel mules and reminded herself of who she was.

LaToya Watkins’ writing has appeared or is forthcoming in A Public Space, The Sun, McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, The Kenyon Review, The Pushcart Prize anthology, and elsewhere. She is a Kimbilio Fiction fellow and has received support from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the MacDowell Colony, Yaddo, Hedgebrook, and Art Omi. She received a Ph.D. in aesthetic studies from the University of Texas at Dallas. She is co-director of the Jack Jones Literary Retreat.

Into a Blue-White Sky

by Blake Kimzey

The day after granddad died, I woke to a weedeater chewing up the front yard. I’d lived for the last decade, since I was 2, with my grandparents in East Dallas on Arturo Drive, a strip of chalk road that dead-ends with the Fraternal Order of Eagles lodge. They were the only mother and father I’d ever known, and in that time one person had worked the weedeater, and he was dead and gone. I knew Granny wouldn’t dare mess up her hive, gassed with hairspray, doing yardwork. Not in a million years. My eyes had been sealed shut with sleep and snot from crying so hard, but an investigation was needed.

The curtains in my room were made from swatches of an old bedspread with MLB logos halved and sewn back together, the fabric so thin from a thousand washes that the sun pushed through, the bedroom aglow at first light and bathed with the liquid blueness of summer. I pulled the curtains apart and saw Granny tangled in an orange extension cord center-lawn using the weedeater as a scythe, moving back and forth over the crabgrass, spitting dirt and pebbles and whole blades of grass airborne. She was after the loam, trying to scalp every inch of grass.

Granny’s cigarette burned against the early rising sun over the short-leaf pines. Across the way: Mrs. Derricks’ face pressed to her living room window; she held a tumbler of gin under her chin. It was early to be weedeating and an odder sight still to behold Granny stirring the small collection of single wides that had been backed in and unhitched years ago. Not a quarter mile away rails shifted above tar-black crossties as a train edged the lawyered estates of Forest Hills, their lawns pushpinned with private-school spirit signs and Teslas parked at showroom angles.

On the lawn, Granny cried through the cigarette in her mouth, lips accordioned around the filter, her slight shoulders bouncing with grief, shoulder blades cutting through her thin tank. I could see that the rest of her life—our life—was unknowable without Granddad. The Schwan’s man had been by just yesterday and brought a cloud of white chalk behind his truck. He offloaded a freezer full of chicken cordon bleu, tubs of sherbet, and every manner of frozen dinner that were staples for us.

Granny had defrosted and baked the cordon bleus, and not an hour after dinner Granddad lurched forward from his recliner and was dead by the time his reading glasses hit the shag in the living room—all 64 years of him; a solid man with roped veins; strong, machine shop hands splayed out at his sides; his eyes rolled up and staring blankly at the line of mesh-backed Vietnam Vet hats he wore out to Saturday breakfast to meet other old-timers at Barbec’s.

Outside, I shouted at Granny, but she couldn’t hear me over the whine and rattle of the weedeater, and I wouldn’t dare spook her, tap on her shoulder, with the extension cord coiled around her ankles. I watched Granny from the porch and squinted through a ball of gnats making atomic circles around my head.

Granny let the tobacco burn to the filter, let it drop from her mouth, then raised the weedeater straight as a rod over her head and throttled it, letting the twine spin until her house slippers tiptoed off the lawn, and then she was fully hovering with the weedeater helicoptering above her. I thought of Mary Poppins, of her umbrella, of her diagonal rise into London fog. And up Granny went, as far as she could go tethered to the cord, rising above the short-leaf pines until the extension cord fell away and slithered in orange free fall until it was back on the lawn and coiled as if Granddad had wound it around his palm and elbow and set it on the ground with purpose and care, the way he lived life.

I visored my palm until Granny was out of sight, her own diagonal rise into the haze of an early summer morning in Dallas, when the light pulses and fuzzes the vision, until its intensity and everything about the day bids you to look away. But I couldn’t look away: Granny rising over the utility easement with latticed transmission towers and overhead power lines. I imagined her sailing over White Rock Lake, a shock of Arboretum color below her, and up into the blue-white sky. I stood there waiting for Granny to return, and as I did, morning turned into day, into night, into a lifetime, until this very today. And here I stand still, an old man rheumy with cataracts, skin thin with sunspots, bones porous and avian, slight and hidden in blades of grass up to my shoulders.

Blake Kimzey is founder and executive director of Writing Workshops Dallas. His fiction has been broadcast on NPR, performed onstage in Los Angeles, and has appeared in McSweeney’s, Tin House, and VICE.

The Watch

by Julia Heaberlin

“Why do you wear a man’s watch?” I asked my grandmother when I was 3, playing with blocks.

“So I will remember to put you to bed,” she replied.

“She doesn’t care when you go to bed,” my grandfather said.

“Why do you wear a man’s watch?” I asked my grandmother when I was 10, cutting out sugar cookie stars.

“Because the numbers are bigger,” she replied.

“Your grandmother can see the gnat on a bullet a mile away,” my grandfather said.

“Why do you wear a man’s watch?” I asked my grandmother when she gave me her pearls.

“It was my father’s,” she replied. “ It reminds me of his heart ticking.”

“Her father never wore a watch,” my grandfather said. “And he had no heart.”

“Why do you wear a man’s watch?” I asked my grandmother when she held my first child.

“To remind me that time heals all,” she replied.

“But she knows it doesn’t,” my grandfather said.

“Why do you wear a man’s watch?” I asked my grandmother while I wheeled her around a nursing home.

“It belonged to Paul Newman and someone might steal it,” she replied.

“Your grandmother stole it from Honest Joe’s Pawn Shop in Deep Ellum when she was only 10,” my grandfather said.

“Why do you wear a man’s watch?” I asked, as she lay dying.

“To hide a terrible scar,” my grandmother whispered.

“And the past,” my grandfather said.

Julia Heaberlin is the internationally bestselling author of Paper Ghosts and Black-Eyed Susans. She lives in Grapevine.

Shorty

by Joaquín Zihuatanejo

Shorty had a curse word for the world stuck in his throat that even the sweetest Boone’s Farm strawberry wine couldn’t wash down. A curse word he slurred effortlessly at everyone who walked down his block of Wayne Street. And it truly was his. While Annette Strauss was the mayor of the city of Dallas, Shorty was the mayor of the 1800 block of Wayne Street.

“You don’t know nothing about no damn dominoes, so step off, youngster.”

“That has got to be the ugliest damn dog on this whole planet.”

“Mr. Ice Cream man! There ain’t no reason to be playing that music that damn loud!”

While just about everybody I knew had only harsh words for Shorty, he made me smile. One unforgiving summer day, he said to Felipe, Aída, and me, “Just call me the bus driver, ’cause I’m taking all y’all to school!” as he slammed the queen of spades onto the small foldout table in his front yard. “Long live the queen,” I said right before I asked if I could use his bathroom. “Go on, damn it, but bring me back a Miller High Life from the fridge on your way back.”

The beer was cold in my palm. As I walked back through his living room, a framed photograph caught my eye, a handsome man in a Marine Corps uniform. Impossibly young. The shoulders of a soldier. The face of a teenager. The death notification letter and the flag folded into a perfect triangle next to the photo were also framed.

The screen door creaked as I opened it. “Damn, you is one slow young man.” I smiled at Shorty as I handed him the beer, which only made him curse me more under his breath. I knew now why he sought solace in the bottom of a bottle, why he had a curse word for everyone and everything, why he was at war with the world. There are casualties of war in far-off foreign deserts. And there are casualties here, too, in my city, with nothing but ice-cold beers and tightly folded flags to hold onto.

Joaquín Zihuatanejo received his M.F.A. in creative writing with a concentration in poetry from the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. His work has been featured in Prairie Schooner, Sonora Review, and Huizache, and his poetry has been featured on HBO, NBC, and NPR. He was the winner of the Anhinga-Robert Dana Prize for Poetry, and his new book, Arsonist, was published by Anhinga Press in September 2018.

Violated

by Sanderia Faye

Ruthie Mae stared across the street at the State Fair of Texas. She lived close enough to see and smell the smoke when Big Tex had burned to a crisp. Some days she imagined her husband was still around, coercing her to ride on the Ferris wheel, trying to recapture their youth. She shook off the nostalgia and picked up the lunch she had packed for her daughter, Shontaye. Every Monday through Thursday for over a year now, she fixed a chicken sandwich, mixed salad, potato chips, cookie, and orange juice and stuffed it in her soft-sided cooler. Dialysis made Shontaye so weak that she needed to eat and take a short nap before she returned to her job training people at the gym. “Whipping them into shape,” she’d said.

Her phone rang as she headed toward the front door. Telemarketers. But wait, maybe it was Shontaye. Ruthie Mae knew she was running an errand with one of the trainers before meeting her at dialysis.

“Mom,” Shontaye whispered. “Don’t panic. Just listen.” Ruthie Mae pushed the speaker button and eased down onto the brown leather recliner that had belonged to her husband before he passed away. “Call my parole officer and tell her I was riding in the car with another felon when the police pulled us over. It’s a parole violation.”

Ruthie Mae interrupted her. “Lordy, Jesus.”

“Mom, listen. They’re going to hold me. My P.O. can tell you what to do. I’m at the Lew Sterrett Justice Center, the Dallas County Jail.” Ruthie Mae picked up the pencil from the end table and wrote Dallas County Jail onto the calendar. “Mom. You there?”

She remembered years ago when Shontaye had called and said she was in jail. That day she handed the phone to her husband to let him handle it.

“I didn’t know he was a felon,” Shontaye said.

Beads of sweat appeared on Ruthie Mae’s forehead. As she searched for the P.O.’s number, perspiration dripped down her armpits and thighs. By the time her call went into voicemail, she realized it was the afternoon of the day before Good Friday and government offices may have already shut down for the holiday. She sat on the side of Shontaye’s bed knowing she would get deathly ill without her dialysis treatment. Then her eyes landed on the row of pills lined neatly on the nightstand. Ruthie Mae gathered the pills and put them into the soft-sided cooler. She decided to take the pills with her to the jail and see about getting Shontaye out before Easter.

When Ruthie Mae arrived at the jail, she signed her name on the 33rd line of the sheet of paper. Then she stood against the wall of the overcrowded room that smelled like fear and hopelessness and waited. She overheard a middle-aged woman like herself plead to no avail with the officer for information about her son. He ignored her pleas and called the next name as he looked past her into the musty room. A woman next to Ruthie Mae with red hair and nails continually stooped down and stood up as if she couldn’t figure out the most comfortable position. After the officer pushed the middle-aged woman aside, she struck up a conversation with Ruthie Mae.

“You see how he violated her? If he put his hands on me, I’d sue his ass off.” Her name was AJ.

“You a lawyer?” Ruthie Mae asked.

“No, honey. You couldn’t pay me to be that sleazy,” she said. “You need a lawyer?”

“I don’t quite know what I need. My daughter was picked up on a parole violation, and I can’t reach her P.O.” Ruthie Mae spilled her story to AJ as if she was her pastor.

“Ohhh,” AJ said.

“What you mean, oh?”

AJ leaned closer to her ear. “She have to wait at least 10 days before she see the judge.”

“How you know all this?” Ruthie said, getting irritated.

“Honey, please,” AJ said. “But maybe since she need her pills and dialysis, they’ll let you bail her out today.”

Ruthie Mae gained a smidgen of hope. “You really think so?”

“Nah,” AJ said. “I don’t.”

Ruthie Mae lowered her head and looked down at the floor. “Should I talk to one of these lawyers?” She showed her two business cards.

“Hell, no,” AJ said, and tore up the cards. “Don’t believe nobody in here except that officer. Write down your three question ’cause he only giving you a minute. You want to know when she going before the judge, how can she get her dialysis treatment and meds.” AJ tapped on the wall with her long red fingernails, which drove Ruthie Mae up the wall. “Look, they can’t take your medicine. Their doctors have to prescribe it for her. She is a ward of the prison not the jail, so she’ll have to follow prison rules.”

Ruthie Mae wanted to hit AJ, smack her up and down the hallway, but deep inside she believed her, knew she was telling the truth. “I’m worried about her health.”

“Ain’t no place for worry in here. Buck up and demand answers. You saw what happened to that other old church lady.”

Ruthie Mae’s wobbly legs could barely hold her up, so she sat on the floor. A dark cloud saturated her mind, and she couldn’t breathe as she read the three questions repeatedly. She called the parole officer again. The last time she had done every second of Shontaye’s time with her and swore she wouldn’t do it again, but here she was waiting as if she was a criminal. The officer called AJ’s name, and she switched up to his desk as if she owned the place. Ruthie Mae’s head hurt, and her armpits and panties were soaked. Later, AJ tapped her on the shoulder before she exited the room. Then Ruthie Mae unzipped the soft-sided cooler and opened the bag of potato chips.

She was alone.

Sanderia Faye is on the faculty at SMU and is a speaker, activist, and sommelier. Her novel, Mourner’s Bench, won the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award for debut fiction, the Philosophical Society of Texas Award of Merit for fiction, and the 2017 Arkansas Library Association Arkansiana Award. She hosts the LitNight reading series, held every second Tuesday of the month at Chocolate Secrets.

The Time My Grandfather Met Bob Hope

by Samantha Mabry

The story goes like this: my grandfather met bob hope sometime in the early 1960s, outside the big hotel on Central and Mockingbird. Back then, that hotel was called the Hilton Inn, but it looks pretty much the same now as it did in the past. Both my grandfather and Bob Hope were waiting for their cars to be pulled around, and Bob Hope was dressed for golf.

This is a major event in my family’s history, but what I just told you is the entire story as I know it. I don’t know why my grandfather was at the Hilton Inn, waiting for his car, and I don’t know why Bob Hope was in town that day, other than to play golf.

I like stories like this, though. I know the building, so I can picture it. I know my grandfather and Bob Hope, so I can picture them. The rest of the details don’t matter much—just two men, saying hello.

Samantha Mabry is a native of Dallas. She teaches English at El Centro College, and her most recent novel, All the Wind in the World, was nominated for a National Book Award for Young People’s Literature in 2017.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author