To grasp the significance of Circo’s opening in Dallas, you must understand the empire of Italian-born patriarch Sirio Maccioni.

It’s a bit confusing. In 1974, Maccioni opened Le Cirque, the famous and Michelin-starred Upper East Side restaurant that was the ne plus ultra of elegant, high-end French dining, haunted by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and other degrees of air-kissing titled or social royalty.

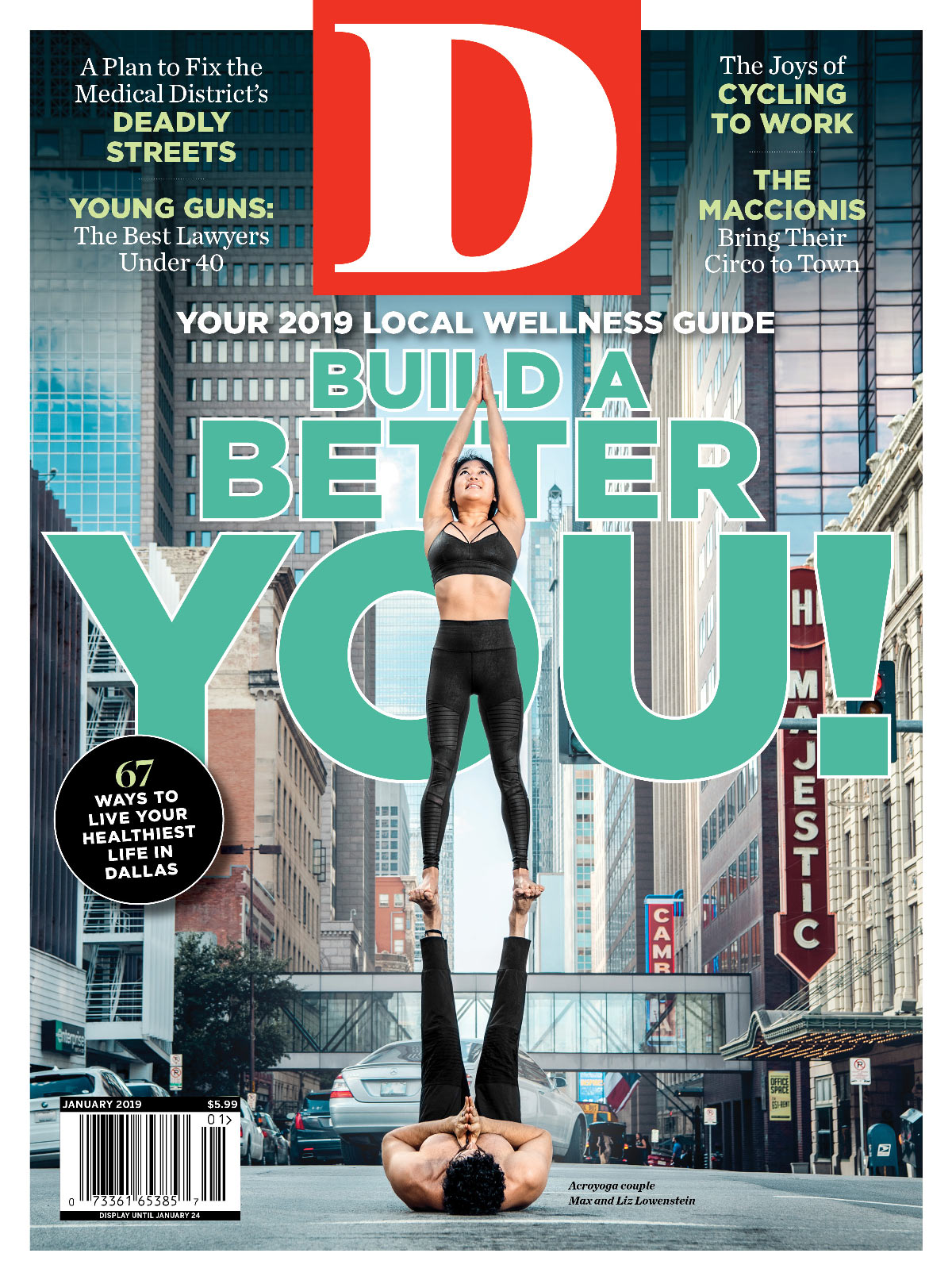

But in 2017, after 43 years, Le Cirque’s owners filed for bankruptcy. The same year, Circo—the Italian-style offshoot that opened later in midtown Manhattan, with a circus-tent grand canopy and the exuberance to match—also shuttered. By then, the enterprise had grown to include a Le Cirque in Las Vegas and a Circo in Abu Dhabi, and was in the hands of Maccioni’s three sons. Then came another twist in the tale: WhiteRock Hospitality, based in Dallas, stepped in, offering to partner with the Maccioni sons to oversee the Le Cirque and Circo names across North America for the next 25 years. Circo Dallas was to be the brave new prototype for a brand that has its sights on Beverly Hills.

But the glitzy opening, long-delayed and much-researched, felt like a series of false starts. The decor has elements of tackiness. The dangling plaster monkey that cannot help but make me think of Michael Jackson’s pet monkey, Bubbles. The glass-bottomed glass pool on the second-floor deck with clear plastic chairs—they call this Circo Beach. The attendant in the women’s restroom who hands you a flute, asking if you would like Champagne. (You don’t, really; you are in the bathroom.) “What kind?” you ask. “Prosecco,” she answers brightly, after tilting both the bottle and her head.

Unlike Abu Dhabi’s Circo, whose menu is Tuscan, Circo Dallas announced it would serve coastal Italian fare. What is coastal Italian? Few on the floor seemed to know. Not the servers, most nights. Not one of the shareholders, who offered a fuzzy definition that involved gesturing as though to a swath of Liguria or Amalfi and gushing that the Bolognese is not over-creamed. To chef Eddie Barron, it means an emphasis on seafood. (His father was a commercial fisherman; he knows the medium well.) Perhaps it can be whatever you want it to be. That seems to be the principle under which the kitchen operates.

On an immense white plate, a New Age blockhouse of romaine comes draped with exactly three cured anchovies. A poached egg that hides under a drift of Parmesan in a hollow, dry brioche sidecar crouton is a gimmick that makes you gasp. Look closer, and you might spy the browned edges of lettuce cut too soon, its flaws covered with more Parmesan.

Here began the comparisons to wedding banquet fare. I felt as though we had time-warped to the ’80s, when chefs impressed with avant-garde presentation. Now, things have to tickle other senses, too. This was followed by the inauspicious appearance of a sodden, greasy fritto misto, done no favors by a duo of lackluster sauces.

Foie gras, that exquisite delicacy, was peculiarly bland, though well-sourced. As a slice of torchon, surrounded by cognac- and honey-soaked compressed pears, it was upstaged by a toasted brick of brioche and seemed to pop only because of the salt.

In a filet mignon Rossini-style, that most classic of dishes, sumptuously topped with a slice of pan-seared foie, truffles, and a Madeira demi-glace (here a beef jus), an abundance of truffle petals were stiff and flavorless as card stock and chanterelles crisp as blackened toast. They accompanied a pale and forgettable lobe. Amid all these trappings was a classic case of over-promising and failing to deliver.

One evening, red snapper arrived with lovely fresh artichoke hearts that are carved in the morning, and green olives, the vegetables rolled in a luxurious sauce vierge; but the snapper itself was not sweet, instead unpleasantly fishy. And 36-hour braised beef cheek, a special one night, resting on house-made pappardelle, was cloyingly sticky, with an oversweet, tacky demi-glace that clung to the roof of the mouth. The dish needed cutting through from the peppery spice with a mouth-filling Chianti.

Which is not to say that everything was dismal. The gloriously thick, wintry Bolognese is very good. The cacio e pepe, meanwhile, made me wonder why I paid $24 for a bowl of buttered noodles. And overall, it seems a very broad menu executed by a team that doesn’t quite have everything under its belt.

The servers will recommend a Pinot Grigio or Chardonnay, but are a bit lost if you ask questions. If pressured, they’ll nudge you toward a Gavi, perhaps hinting it’s most like Chardonnay. It’s a shame, as Aaron Benson, a fine sommelier, was at Circo long enough to craft an excellent wine list. Under his direction, this could be a place for a Barbera d’Asti or Brunello, or a crisp, dry, little-known Italian white, perfectly chilled.

One thing they do very well is lobster. The Le Cirque lobster salad is a lovely ring, with avocado, asparagus tips, and nasturtium leaves. Or baked lobster itself, fresh as though just plucked from the sea, the meat succulent, sweet, and pristine, though the presentation with herbed bread crumbs lands soupy and gluey. (The kitchen has changed a number of items, and the stuffed lobster is one of them.)

Originals from Le Cirque fare well in their respect for quality and simplicity. Most notable is the iconic Le Cirque crème brûlée, decadent and silky, that crackles and then slips over your tongue. It was far better than a Grand Marnier souffle served with a quenelle of orange sorbet that joined in an impression like hot marmalade. Or an awful assemblage with a sable crust (more like a dull, undercooked wafer), a curious balsamic zabaglio-

ne, and slivers of unripe poached pear stuck in like razor blades—the unfortunate totality set jauntily to the extreme edge of the plate.

On a Saturday night, when patrons are dressed to the nines—a little girl in her going-out dress and a large party in sparkling, head-turning, floor-sweeping gowns—it seems to achieve what Circo Dallas aspires to be.

But there were so many times when I was baffled by the collision of gaffes and high price point.

“Let it go,” my dining partner mouthed, the night a server returned to murmur that they couldn’t make my macchiato, as they lacked the caramel syrup. I blinked, and then I did.