A few minutes before 7 a.m. on a January morning in 2015, 61-year-old Randal Dygert stepped into a crosswalk that cuts along Harry Hines at Medical District Drive. He likely didn’t see the shuttle bus coming. Dygert died on impact. He was then dragged 50 yards northbound, along Harry Hines. The bus also struck a woman walking nearby. She was rushed to Parkland Memorial Hospital, where Dygert had worked for more than three decades. She survived her injuries. Police would later tell reporters that the registered nurse had been walking across the intersection during a shift change.

This area, the Southwestern Medical District, is hostile to pedestrians. The intersection where Dygert was killed is a field of concrete, seven lanes separated by a 3-foot median accented with yellowing grass. Cars barrel up and down Harry Hines at all hours of the day. The stoplight at Medical District Drive is just an annoyance. There is no tree cover here, either, leaving the sun to scorch everything below it—cars, people, concrete, traffic lights.

None of this makes sense. The district spans 1,000 acres and is home to three of the state’s most renowned healthcare institutions—Parkland, UT Southwestern Medical Center, and Children’s Health System of Texas. More than 29,000 people work here, and nearly 3 million more visit its clinics and emergency rooms every year. It would seem that, at the very least, we could provide safe, shaded places for those people to walk.

We have inherited this failure. The Medical District is just 3 miles up Stemmons Freeway from downtown Dallas, but this was once the northern edge of town. Before Parkland opened its first campus here, in 1952, it was a manufacturing district. Medical District Drive was once known as Motor Street, so named for the wide lanes that led large vehicles in and out. As Dallas stretched north, though, this became the center of the city. In 1955, UT Southwestern moved the school from what is now Oak Lawn over to its present location along Harry Hines. Children’s became a full hospital in 1960. The hospitals have only sprawled since.

“I’m really hoping that we can bring a new vision of how we create our cities, because that is our legacy that we leave. Now that we know, we’ve got to change.”

The infrastructure hasn’t kept up. There are 21 miles of public streets here, but only 12 of those miles feature adjacent sidewalks. In fact, sidewalks along Harry Hines, a 78-year-old highway that was once Dallas’ only route to Denton, force walkers within arm’s length of the cars that zoom past them. And that’s when there’s actually a place to walk; the sidewalks often disappear along the road, which moves up to 40,000 cars every day. Thousands of doctors and nurses and other providers have few options when it comes to restaurants, coffee shops, or places to live. Families of patients in the hospitals can’t exactly take a walk through a manicured garden to put themselves at ease. To walk here is to feel as if you’re being punished for not being in a vehicle.

It’s also the hottest part of the city. Thanks to its miles upon miles of concrete, this is Dallas’ largest urban heat island. Tree canopy covers just 7 percent of the Medical District, well below the 40 percent that arborists recommend to reduce ambient heat. That means the sun’s rays hit the cement and soak in, causing heat to radiate outward. With so little tree canopy, an urban heat island like this one can actually be 50 to 90 degrees hotter than the reported temperature.

This is an area dense with utilities and infrastructure—and it’s all baking. The long-term effects of this read like an apocalypse in slow motion: electricity and water systems can fail during periods of high demand, power lines expand, pipes crack, concrete splits. Because of Dallas’ poor citywide tree canopy—the vast majority of which is concentrated south of the Trinity River—ours is the second-hottest city in the country, trailing only Phoenix. And ground zero is the Medical District, one of the city’s greatest economic assets and sources of pride.

But there is a plan in the works to make this area safe for pedestrians while lessening the impact of the sun. It starts with an unassuming woman with a green thumb.

Janette Monear sits below a potted ficus in her office at the headquarters of the Texas Trees Foundation, the nonprofit she runs out of a converted Victorian home along Swiss Avenue, in Bryan Place. Monear, 71, has a comforting smile and a neat mop of salt-and-pepper hair that she swooshes over her forehead. She speaks softly and would honestly rather listen, but she has been asked to recall the dizzying number of people she’s had to convince that her organization really can start with $51 million and transform the Medical District.

A quick rundown of the players: there’s the city of Dallas, including staff planners, Councilman Adam Medrano, and the mayor; Dallas County; the philanthropy class, including The Eugene McDermott Foundation and people like Lyda Hill, who has helped pay for some of Texas Trees’ initiatives; the North Central Texas Council of Governments, which oversees the traffic studies and helps secure public funding sources; federal officials, people like Democratic U.S. Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson and outgoing Republican U.S. Rep. Pete Sessions (after the November elections, Monear has to get his replacement, the Democrat Colin Allred, up to speed); the individual hospitals; the board that manages the Medical District itself; and last but not least, the surrounding residential neighborhoods that will likely be impacted by the economic development that this project will bring.

All Monear has to do is untangle that rat’s nest of interests held by all those stakeholders. She agreed to lead the organization more than a decade ago because she believes the environment and public spaces are interconnected, that one can benefit the other. The organization’s research has built toward proving this argument. Dallas’ Medical District is her laboratory.

“I’m really hoping that we can bring a new vision of how we create our cities, because that is our legacy that we leave,” she says. “I don’t blame anybody for the lack of open space, because we only know what we know. But now that we know, we’ve got to change.”

Texas Trees’ plan is among the most ambitious the city has ever seen. It involves nearly all 1,000 acres of the district, including modifying public right of way and connecting it with private property.

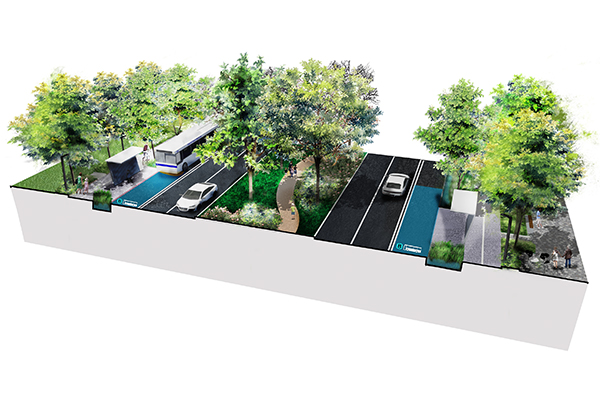

To grasp its scope, start at Harry Hines and Lucas—a side street a few blocks up from Wycliff—and drive two miles north, all the way to Mockingbird, just past UT Southwestern’s William P. Clements Jr. University Hospital. The project refers to this stretch of Harry Hines as the Green Spine, so named because it is the primary way in and out of the district. Texas Trees wants to turn the existing median into a pedestrian promenade, adding a tree-lined walking trail down the middle.

As for traffic, there are currently six lanes, three in either direction (not including turning lanes). Both directions have a lane that is dedicated for public transit, separated by a double white line. Drivers don’t exactly respect it. The project keeps cars out of this third lane. In the future, Monear envisions autonomous shuttles ferrying passengers to and from downtown, unencumbered by vehicular traffic. For cyclists, the forthcoming Trinity Strand Trail—which has $3.3 million in 2012-era bond dollars allocated to it—will run adjacent to Harry Hines for about two miles, along the DART rail tracks, connecting the Design District across the Trinity River to the Medical District.

Its end goal is to plant 6,500 trees throughout the district and add 21 miles of sidewalk to the existing 12—three quarters of which will be farther than 6 feet from the street itself. It envisions shared lanes, park space, and ground-level opportunities for retail and restaurants. It also has a goal of capturing and treating 1.2 million cubic feet of rain annually. This is referred to as the Green Quilt, a strategy to increase tree canopy and incorporate innovative storm water management, drainage, and reuse.

“As we work in all of the district,” Monear says, “we’re bringing continuity through trees and green infrastructure.”

If this mix of environmentalism and urban design works, it’s not difficult to envision private developers running over one another to get to this part of the city. The critical mass of people needed to jump-start the change is there. All it is missing is the infrastructure and the vision.

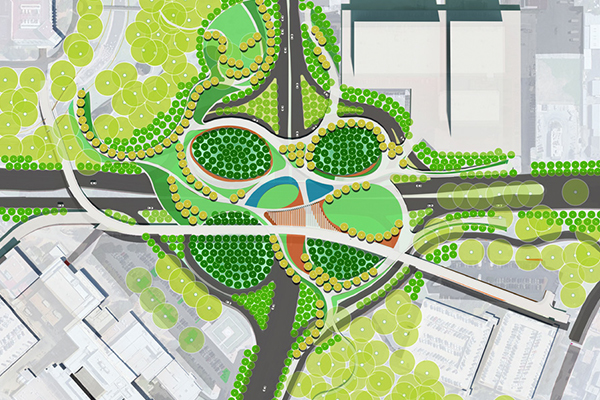

The nonprofit needs to prove that Harry Hines, which runs adjacent to Interstate 35, is primarily used as a cut-through for drivers looking to get downtown from points north. The group wants to rethink the most trafficked intersection in the district—Inwood at Harry Hines, which is a major thoroughfare for traffic exiting I-35 and heading east. The most ambitious part of the project is also its most beautiful selling point: the so-called Green Heart, which would move all north- and southbound traffic along Harry Hines at grade and transform the existing elevated roadway into a 7-acre public park.

It is hard to imagine. That intersection is the busiest in the district, a wall of cars zipping by in all directions at all hours of the day and night. Monear believes these drivers are passing through, using the road for what it was designed to do: move traffic. If you’re headed north or south on Harry Hines, you’re sailing above Inwood on an elevated roadway. There are no pesky stop signs or stoplights to get you to brake. A cloverleaf shoots cars off onto Inwood, joining the traffic that has just exited Interstate 35 or is speeding toward it.

Pedestrians have no place here. The Green Heart would force all traffic to grade at Inwood, slowing it as it passes through the Medical District. Monear believes this would motivate drivers to find other ways to get downtown, away from the hospitals. Freeing up the elevated roadway means having somewhere around 17 acres to play with. A portion of this will be the park, flanked by a bird sanctuary and O’Donnell Grove, that stretch of trees and grass on the southwest corner of Southwestern’s northern campus. The Green Heart will connect the university’s north and south campuses, which are currently bifurcated by Inwood. Pedestrians will finally be able to cross that street, and they’ll have gathering spaces, gardens, dog parks, and vantage points.

“That is the center of the district,” Monear says. “It’s also probably one of the worst areas in the district, in that you cannot cross Harry Hines without putting your life in jeopardy. You cannot cross Inwood very well. You certainly can’t ride a bike. What we looked at is, OK, how do we create this space that will be conducive to pedestrian and bicycle access and not so much worry about the street, that highway? How do we create that space so it’s more of a huge plaza?”

This wasn’t the sort of thing that Texas Trees was established to do. Real estate magnate Trammell Crow founded it in 1982 as a way to support Dallas parks. He drummed up support from the business community and got Dallas Morning News publisher Robert Decherd to collaborate. Crow got most of the trees from his own farm in East Texas. As it grew, the organization mostly did one-off projects around new developments or in various neighborhoods. It was a noble cause, but there wasn’t anything systematic about it. That changed under current chairman Bobby Lyle, the engineer and philanthropist who was once the executive dean of SMU’s Cox School of Business.

“We really didn’t have a plan for how we were going to have a major impact on the region,” he says. “We really needed to know what parts of the city have the greatest need for a tree canopy.”

Up until 2017, the city of Dallas had no forestry division, making it one of the largest American cities without one. Texas Trees has, in some ways, stepped into that void. Monear was hired in 2007 and began mapping every tree in the city of Dallas. The organization put together a road map to tree planting and planning. It analyzed all the open spaces in the city that it could cover in green. It logged a total of 14.7 million trees, and found that they have a replacement value of $9.02 billion, basing that number on size, species, and condition. The city’s overall canopy is at 29 percent, with 37 percent of it below Interstate 30. About 38 percent of Dallas is covered in “impervious surfaces”—buildings, roads, streets, parking lots.

“It’s no wonder we flood all the time,” Monear says.

So, yes, flooding, but this is also a public health risk. All of this is explored in Texas Trees’ landmark 2017 study of the city’s urban heat islands, which was done in tandem with the Urban Climate Lab of the Georgia Institute of Technology. It is one of the largest such studies done in the history of the United States. Its guiding principle is this quote from the author and co-researcher Brian Stone: “Cities do not cause heat waves—they amplify them.”

A 2008 study of nine counties in California found that every 10-degree spike in temperature correlated with a 2.3 percent increase in mortality. In the summer of 2011, Dallas had 70 days that hit over 100 degrees. Forty of those days were consecutive. Fifty-three people died of heat-related issues. It will almost certainly get this hot again.

“Increased tree canopy is found to offset mortality most significantly to the north and northeast of the downtown district,” the study reads.

And while the city’s tree canopy covers 29 percent of our land mass, that coverage isn’t close to uniform. The sparsest canopy coverage, at 7 percent, belongs to the Medical District. That’s how Texas Trees identified its project.

Monear grew up in Iowa. There is no Johnny Appleseed sort of origin story here; she actually worked inside. At a bank. She married young, while attending Iowa Wesleyan University. She and her husband transferred to the University of Northern Iowa, and her parents helped him get through college. “That was the point in time when they wanted a man to take care of their daughter,” she says.

So she got a job. She took classes when she could, but she made ends meet by working at the bank where she spent her summers before college. Monear started as a teller, but basically did everything else including managing trust funds. She eventually became the bank’s director of advertising, overseeing its transition into the second electronic banking center in the country. Her husband wound up being transferred to Minneapolis, and she went with.

“I didn’t know anybody,” she said. “I had two small children. One was in second grade and one was in third grade. I started doing volunteer work and I worked part time at a little nursery, just because I wanted to meet people.”

She made a decision to stick with school and not work. At that nursery, she’d help customers design their small gardens. She liked the planning that went into that—which plants to buy, where to put them in the dirt. She’d taken a few landscape design courses in Iowa and decided to give that a shot at the University of Minnesota. She quickly drew the attention of Dr. David French, a professor and internationally renowned plant pathologist who was studying why oak wilt was killing thousands of trees around the state. He asked her to come work for the university.

“I asked him why,” she says. “He said, ‘Because you can turn nothing into something and I need to know what you know. I’ll teach you everything I know.’ ”

It’s here that her background starts dovetailing with what she’s doing at Texas Trees. She and French learned that Texas had an oak wilt problem, too, and the pair appealed to J.J. Pickle, the congressman from Big Spring who was on the House appropriations committee. He got millions for their research from the U.S. Forest Service. She helped run a program for at-risk youth and adult ex-cons that involved planting trees around things like retaining walls and creating boardwalks. She spent many hours working with the Minnesota state legislature, lobbying for money for trees. At one point, she invited some legislators to breakfast, then took them up in a helicopter so they could see how sparse the tree canopy was.

“You can see these big, dead areas of trees, and they asked what that meant,” she says. “It meant that it affected the air quality. Then they knew it was a challenge.”

She has a way of marketing concepts that, on their own, could make the people she’s talking to more interested in the type of tile they’re standing on than what’s being said to them. She got Minnesota’s largest developers and builders to buy into private tree planting by starting an awards program that put them in competition with one another.

“I can see the big picture, but I can connect the dots,” she says. “Most people can’t connect the dots.”

“I’m really hoping that we can bring a new vision of how we create our cities, because that is our legacy that we leave. Now that we know, we’ve got to change.”

Trees are communal. This is how she came around to urbanism, too. In Minnesota, her home sat on a cul-de-sac outside the city, the type of neighborhood where people pull their cars into their garages and you don’t see them again. They had land—there was something like 3,000 acres behind them, all covered in trees and wildlife—but the people were missing. It was lonely. How many other parts of the city were like that? She began working with communities of various ethnicities, Southeast Asians, Native Americans, African-Americans. She used trees as a way to bring these people together. She started organizing tree planting projects. They had barbecues. They built pocket parks so that their kids could play together.

When she came to the Texas Trees Foundation in 2007, she knew what she wanted to accomplish. It was in line with Lyle’s vision: make an impact on a city of concrete. Get people together. Change the urban design that has prioritized cars over pedestrians.

“The Southwestern Medical District, it’s all the people,” Monear says. “We have to think about the different cultures, the different people that are coming, because every culture, all chapters, everybody comes to the district. Everybody in the region at some point in time will probably use one of those three hospitals.”

Texas Trees plans to make its grand statement at the cloverleaf formed by the intersection of Inwood and Harry Hines. The organization wants to eliminate the bridge and bring all traffic to grade. Traffic will be slowed. The space will become a giant public park filled with walking trails covered by trees.

“These are all walkable distances,” says the renowned landscape architect Peter Walker, who is a conceptual designer for part of the project. “So how can we make the linear experience not just for the cars, but get people on them? Get bikes on them. Make them memorable and useful and design them in a way that you can remember them.”

Some of this work is already happening, without the final plan in place. Joe Tillotson, one of the original owners of the Katy Trail Ice House, is opening a 10,000-square-foot bar and restaurant on Butler Street, just off Harry Hines. More than half of that is patio space.

The first phase of the project—the main portion is redesigning Harry Hines—should cost about $51 million. The organization has raised about $18 million of that—$7.5 million from a city bond program, $7 million from the NCTCOG, $2.5 million from Lyda Hill, and half a million from the McDermott Foundation. Monear believes that starting the project will help convince philanthropists to open their wallets, and our elected representatives are helping Texas Trees get the project included in state and federal grant programs. Texas Trees will oversee the design and then hand it over to the city to build it. They want to start construction by 2021.

“We’re going to have to execute phase one perfectly, but once that’s executed we can show that as a model of success,” says Majed Al-Ghafry, an assistant city manager. “People are not going to buy fish in the sea; people are going to buy fish from the fish market, after they see it with their own eyes. We don’t have a choice but to pull this off.”

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author