Before they changed the game of bridge, before they captured the United States’ first world championship in more than 15 years, before the million-dollar computer and celebrity hangers-on and discipline imparted by a former Air Force colonel named Moose, the Dallas Aces needed to fire their boss.

Before they changed the game of bridge, before they captured the United States’ first world championship in more than 15 years, before the million-dollar computer and celebrity hangers-on and discipline imparted by a former Air Force colonel named Moose, the Dallas Aces needed to fire their boss.

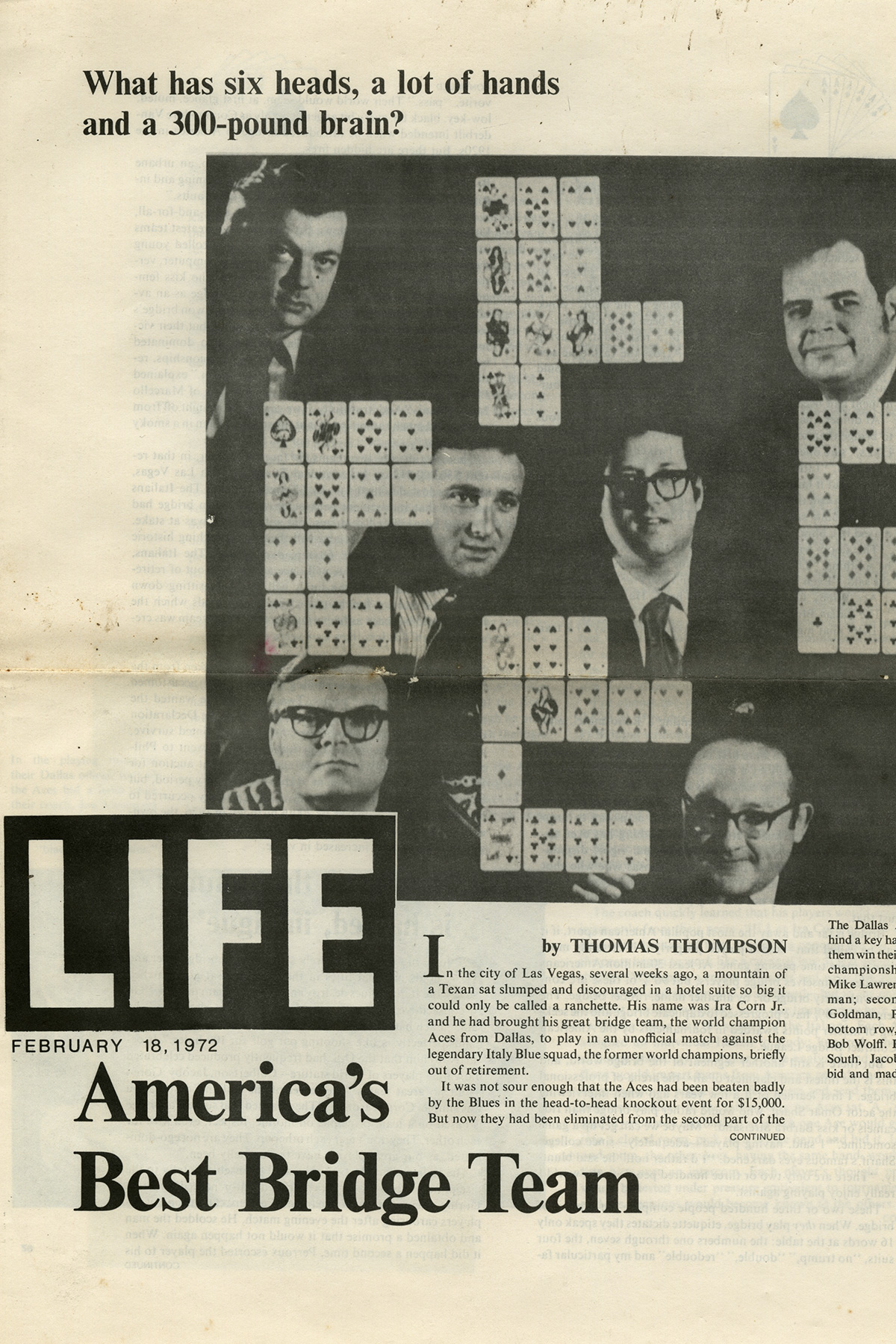

Ira Corn was a unique presence, a 300-pound multimillionaire with a proclivity for throwing his financial weight around. “He was large, so he had to live large,” says his daughter, Laura. There were conventional luxuries: fine art, rich food, cigars the size of Lincoln Logs, a penthouse apartment in Manhattan. But he reserved his most grandiose spending for his passions. He loved American history, so he purchased an original copy of the Declaration of Independence for $404,000, the highest price ever paid for a printed document at the time. He loved to read, so he subscribed to dozens of periodicals and finished a new book each night.

Most of all, in 1968, he loved bridge. So he decided to bankroll a professional team—even though one had never existed before. He had designs on toppling Italy’s famous Blue Team, the game’s great juggernaut, winners of 12 of the last 13 world championships. Not only that, he intended to defeat them himself.

“He thought if he got five good players, he could play with them and win anything,” says Mike Lawrence, one of the team’s original members. “That was the furthest from the truth imaginable.”

Which is what led Bobby Wolff, the team’s first recruit and Ira’s handpicked partner, to pull his benefactor aside on a Tuesday in late August. They were in Minneapolis for one of the most important events of the year, the Spingold national bridge championship. Five days in, their team was treading water, eking out victories over opponents they should have dismembered. It had been that way ever since the Aces were formed that February, a collection of world-class talent lugging along an amateur. Finally, after one close call too many, “the time had come for truth,” Wolff says now.

Wolff broke the news in a hotel hallway, as Ira puffed a typically giant cigar: The Aces will never become what you want them to be—what they can be—if you keep playing. Ira said nothing. Wolff half-expected Ira to dissolve the team, and perhaps that wouldn’t be the worst thing. Ira had the best of intentions but he was dragging his creation down. And then, as Wolff began to plot out his next endeavors, Ira spoke.

“Well, you better win,” he grumbled. They lost the next day.

One year later, they routed the field. By then the Dallas Aces were in the throes of one of the most audacious experiments the game had seen, an unprecedented and mostly unduplicated attempt to build a better bridge team. When they dissolved after 15 years, the Aces had collected four world titles and numerous domestic championships. Two of their stars formed one of the most decorated partnerships in history. Along the way, they prototyped strategies that are now ubiquitous in modern sports culture.

The story of the world’s first full-time professional bridge team is one of Dallas succeeding where the rest of America failed. It all owes itself to a large man who chased an appropriately huge dream.

♠

Much like the game itself, bridge’s origins are complicated. One enduring theory traces its roots to a popular 19th-century card game called whist. Another credits it to British soldiers serving in the Crimean War. The modern version, called contract bridge, was invented in 1925 by Harold Vanderbilt, scion of the famous American family. The skeleton resembles spades, with a two-versus-two format in which partnerships bid upon and then attempt to win a set number of hands each game. The musculature is far more intricate, a nexus of coded language, bluffing, and endless strategic calculations.

Despite that, Vanderbilt’s creation soon invaded popular culture. Bridge was both socially and mentally stimulating, a recipe for success among married couples and movie stars alike in the days when radio was limited and television was in its infancy. Charles Goren, one of the game’s first stars, graced the cover of Time magazine. By the 1940s, 44 percent of American households featured at least one bridge player.

Ira G. Corn Jr. was among them. He grew up in Little Rock, Arkansas, the son of a Baptist barber with little use for leisure and none at all for cards. Ira Jr., then, picked up the game later in life, and only in earnest after moving to Dallas in 1948. His first job in town was at SMU, where he taught marketing. But he found his calling in business, ultimately founding or co-founding 24 different companies. The flagship was Michigan General Corporation, a conglomerate of previously sinking businesses—a book publishing imprint in Los Angeles, a street sign company in Chicago, a refinery in Missouri. Over time, he earned a reputation as one of the city’s boldest corporate executives. He cultivated another for how quickly he’d burn through the resulting windfall.

“He would tell you he was the worst steward of money,” says his son, John. “It meant nothing, because he spent it as fast as he got it.”

That made him exactly the sort of man to stake a radical idea. Professional bridge is contested by teams ranging from four to six players, with two partnerships actively playing at all times. In the 1960s, those teams largely functioned as loose confederacies. What few professional sponsors did exist mostly handled expenses on a tournament-by-tournament basis to burnish themselves with the best possible supporting cast. “A George Steinbrenner-type guy playing center field,” says Mike Becker, who would later join the Aces in 1982.

No wonder teams like those couldn’t match up to the Italians. There was no synergy, no development—because there was no environment that provided a suitable amount of time, money, and patience to foster them.

But what if there were? That was the question that Wolff, a San Antonio-based bridge pro, and Dorothy Moore—Ira’s paramour, bridge partner, and corporate secretary at Michigan General—pondered in the mid-1960s. The two had struck up a friendship through the Texas bridge circuit; Moore and Ira also occasionally teamed with Wolff’s then-wife, Betsey, at tournaments. Wolff knew that Ira had the means and passion to invest in such a project. Moore knew that she could persuade him to pursue it.

For Ira, it was a unique opportunity. Between teaching and his work at Michigan General, he’d spent much of his adult life attending to other people’s ventures. Here was his chance to create one from scratch—something he stood to gain immense credit and, in his mind, financial reward for if it succeeded.

There was also another, more principled motivation. For years, parts of the bridge world suspected the Blue Team was cheating. They had simply won too often and too consistently with a roster that ran three deep with star players instead of a full six. There was no solid proof, however, which flummoxed their competitors.

“You knew it, but what are you going to do about it?” Lawrence says.

That didn’t sit well with Ira, who was so compulsive about fairness that, for all his free spending, he documented his corporate expenses down to the penny on the back of his plane ticket after each business trip. “He was not interested in cheating or anybody that couldn’t tell the truth,” says Laura Corn. Defeating the Italians was about more than pure ego. In Ira’s mind, returning the world championship to the United States would be righting a cosmic wrong.

The plan was set in motion in the fall of 1966. Starting with Wolff, Ira would assemble a team of elite talent, whose members would then move to Dallas. In exchange, he would not only pay their expenses but salaries, too—$800 a month for single players and $950 for the married ones. The team would train out of his two-story home on Forest Lane across the road from The Hockaday School, where Ira converted his garage into a practice den. And they would be called the U.S. Aces, later changed to the Dallas Aces to formalize a colloquialism the rest of the bridge world called them.

All that remained was to fill out the roster, a task Ira entrusted to Wolff. It was the break the 34-year-old pined for. Wolff was a well-regarded player in search of a path: he trudged through law school by day, operated a fledgling bridge club by night, and had little to show for either financially. The Aces represented purpose, as well as a decent living.

His first target was his friend Jim Jacoby, a Richardson native who was the son of American bridge legend Oswald Jacoby. At 34, he was already something of a bridge lifer—he won his first national title at age 22. He was also battle-tested against the Blue Team, having narrowly lost the 1963 world championship final as a member of that year’s American team.

With Jacoby in the fold, Wolff then went recruiting. He put out feelers to four players in the summer of 1967: Chuck Burger, a lawyer and bridge pro from Detroit; Toronto-born Sami Kehela; and Bob Hamman and Eddie Kantar, a successful pair out of Los Angeles. Each one declined.

So he dug deeper. He called Lawrence, a 27-year-old from Berkeley, California, who picked up the game in college after a chemistry experiment went awry, injured his hand, and forced him to postpone finals until the following summer. He spent the ensuing three weeks immersed in bridge, soon distinguishing himself through a preternatural game sense and a near-photographic memory. He was the team’s youngest player and also its quietest. Sports Illustrated once described him as a “curiously detached young man.” Lawrence believes a better description at the time would be “quite socially retarded.”

There was also New York’s Billy Eisenberg, a 30-year-old better known as “Broadway Billy.” He was everything the nickname suggested: flashy, outgoing, and sometimes mercurial, both at and away from the card table. Eisenberg palled around with Hugh Hefner and once ran his own card den on Long Island. He was prone to playing late-night marathons of backgammon, a game at which he was perhaps even better than bridge.

“I was the guy who basically ran [to] my own drummer,” Eisenberg says. “I basically did what I thought was OK within reason.”

Finally, partly at Eisenberg’s behest, there was 29-year-old Bobby Goldman. A Philadelphia native and college dropout, Goldman developed a taste for cards in childhood when, as a 7-year-old, he played poker and blackjack for bus fare. In adulthood, his jobs ranged from dealing rare coins to running a Jamaican import business. His colorful past, though, obscured a serious nature. No one was more meticulous.

“He was the one who would come to the meeting and after we talked for two hours … would call out, with this yellow business pad, ‘No, I have 82 more questions,’ ” Lawrence says.

♠

In February 1968, the Aces got to work in Dallas. The first six months were a slog. The team’s coach, Monroe Ingberman, specialized in bidding strategy, which quickly proved superfluous for five professionals with defined ideas on how to play. The skill he lacked was the one the Aces needed most—discipline. Weekdays were minimally structured, which led to minimal productivity. Middling results became the norm.

Then, two crucial things changed. First, a few weeks before the Minneapolis Spingold, the Aces made a coaching change. Joe “Moose” Musumeci was an archetypal hard-ass, a Brooklyn-born former Air Force colonel who spent 21 years in the service. Upon retirement, he began a second career as a bridge pro in San Antonio, where he met and co-opened a bridge club with Bobby Wolff. Now, his unique blend of skills was needed in Dallas. Moose demanded punctual attendance, meted out aerobics training, issued fines for poor conduct, and wasn’t above sternly worded memos. But, like any great coach, he understood his audience. He looked the other way when his players walked instead of jogged, and he concluded one especially memorable directive during an event in Cleveland by telling them to be in their rooms no later than 2 am, “with no more than one visitor.” Moose pushed often and pulled back just enough to earn the team’s respect without becoming despised.

“The single most important thing we did,” Wolff says. “Instead of a bidding coach, we had a disciplinarian. It was a night and day difference. … Without that, the Aces would not have been successful.”

By the end of the year, they were rounding into form—and Bob Hamman, one of the targets on Wolff’s original list, had taken notice. He marveled at the team’s growth, so much so that he reconsidered his initial rejection. “I said, ‘My God, this thing is working. These guys are getting better and they’re getting better fast,’ ” Hamman recalls. “I said, ‘To hell with it. I’ll take my chances if the offer is still open.’ ”

He arrived in Dallas in January 1969. The Aces were now complete. Inevitably, they were better, too. A sixth player ensured partnerships could remain static after months of mixing and matching to accommodate an odd number. Better chemistry and table play would soon follow. But Hamman was hardly roster filler: he had finished runner-up for a world championship two times. “We all knew he was probably the best player on the team when he came,” Lawrence says.

Gradually, they eased into a routine that would mold them into champions. Practice matches were held from Friday night through Sunday morning at Ira’s house, sometimes against the best of the local scene but more often versus elite national competition that Ira flew in. Those matches were then reviewed on Monday and Tuesday in a process Musumeci adjudicated like a courtroom, creating and color-coding a system of charges that were levied against the players’ every misstep. Each hand was reviewed, each action scrutinized. Then, on Wednesday and Thursday, the individual partnerships fine-tuned strategies, before the process reset itself all over again. “Some of us had more to learn or more skills than others, but every one of us maxed out their potential,” Lawrence says. They chipped away too long and too hard at their weaknesses for any other outcome.

“These six players got to play against each other for hours, every day. No one did that,” says Ron Rubin, who joined the team in 1982.

When sheer hours couldn’t solve a problem, creative thinking usually did. Each partnership wrote up extensive notes documenting their strategies, a seemingly obvious idea that no one apart from the Blue Team had tried. They practiced sitting in different rooms and bidding over an intercom to eliminate any reliance on nonverbal cues. Eisenberg and Goldman’s partnership was beset by personality clashes, so Ira sent them to therapy decades prior to sports psychology emerging as a cottage industry.

Then there was the computer. The SDS 940 was shaped like a toaster oven, retailed for $1.5 million, and later would become the first device to ever connect to the internet. For Ira, it was simply a toy purchased for Michigan General that he invited the Aces to tinker with, should anyone be interested. Goldman was. He painstakingly taught himself to code, then programmed the computer to spit out the probabilities of optimal starting hands. He’d print them out, one page every five minutes, and the team would simulate games based off the template. It was almost comically ahead of its time: the Aces built their own primitive analytics program while the competition didn’t even hold practice rounds.

Finally, the pieces were fitting together. Still, as spring turned to summer, the mood within the team was uneasy. Hamman remembers a palpable dread that Ira could fire everyone if the team didn’t win the 1969 Spingold, the one-year anniversary of his ouster from competition.

Instead, they steamrolled the opposition. One elimination match grew so lopsided that the other team forfeited. It was the signature victory the Aces craved, one that validated so many strained hours. For the first time, their goals felt achievable. The 1970 world championship could be their chance to take down the Blue Team.

“It was proof in all of our minds that, Hey, we can do this,” Lawrence says. “All of a sudden, it was clear that we could win.”

The showdown didn’t happen.

The Aces held up their end of the bargain, breezing through qualifying to advance to the Bermuda Bowl, the championship round robin tournament, which, despite its nomenclature, was held that year in Stockholm. The Blue Team, however, was nowhere to be found: they abruptly retired months earlier for unexplained reasons. The Italians did enter a team, one whose talents bordered on amateurish. If the Blue Team was imposing, this team was almost cuddly.

“They were very nice, lovable people—almost like playing against children,” Lawrence says.

The Aces trounced them. They did the same to China in the finals, more than quadrupling their score over a four-match contest. The United States, birthplace of modern bridge, had captured its first world championship since 1954. For the players, it almost felt anticlimactic. They entered as overwhelming favorites against a field that, by their own admission, was hopelessly weak. Winning didn’t give way to triumph so much as relief for doing exactly what was expected of them.

The team’s founder, however, was jubilant. Almost 50 years later, Laura Corn describes it as the proudest achievement of her father’s life.

“Imagine just bankrolling that team, the commitment he had to that team, to doing something that no one had ever done before,” she says. “It was his great passion … [and] like the song, he did it his way.”

♠

The Dallas Aces repeated in 1971, this time defeating a formidable French team. By then, the team had made its mark culturally. Its members were, for all intents and purposes, sports stars. Ira landed his own syndicated bridge column, titled “The Aces on Bridge.” He invited celebrities like Phyllis Diller, George Burns, and Meredith Baxter to his home for Sunday brunch, and they’d cap off the afternoon by playing bridge with him, Wolff, and Charlie Weed, who handled acquisitions for Michigan General. The team befriended Omar Sharif, who twice took them on tour for a series of exhibitions against his Traveling Bridge Circus, half of which was comprised of former Blue Team members.

But by 1972, Ira’s gambit to make the Aces profitable had failed. He revised the terms of the team’s arrangement, still paying tournament expenses but no longer furnishing salaries. Gone were the two-day match reviews and scrimmages and inventive training methods. Eisenberg left, too, the financial changes intermingling with a long-standing desire to try something new. (“They wanted a kind of conformity,” he says. “Well, I didn’t particularly care for that.”) It marked the end of the team’s first, and best, stage of play.

There was also another development—the Blue Team had come out of retirement. The now two-time defending champion Aces hungered for a shot at the opponent they were built to beat.

“We also had a point to prove: that we were not flashes in the pan, good enough to win only if the Blue Team wasn’t around,” Wolff wrote in his memoir, The Lone Wolff: Autobiography of a Bridge Maverick.

The Aces and the Blue Team would square off in the next three world championships. The Italians won handily every time. Then, in 1975, they played one last final at the Bermuda Bowl (this time actually held in Bermuda). It would be marred by a scandal that validated years of suspicion about the Italians’ play. Midway through the final, an American journalist named Bruce Keidan noticed one of the Italian pairs tapping feet under the table in an apparent bid to relay information about their respective hands. Despite the incident being confirmed by multiple witnesses, event administrators allowed the match to continue without penalty—nevertheless taking care to install wooden barriers under the table. The Blue Team won yet again. Each loss bruised the Aces’ record a little more, but the most bitter pain was symbolic.

“Everybody had the idea that a good team is going to be able to beat an OK team that’s cheating,” Lawrence says. “That turned out to be incorrect.”

Lawrence and Jacoby had left in 1973, while Goldman quit the following year. By 1975, Wolff and Hamman were the only two original players remaining. But optimism surged again in early 1982. Hamman recalls Ira feeling rejuvenated, more enthused about the Aces than he had been in years. Four new younger players joined Wolff and Hamman, eager to pursue another world championship.

Ira didn’t live to see it. On April 28, he asked Moore to drive him to the hospital prior to a corporate board meeting. He insisted on walking in under his own power, then collapsed before he could get checked in. He died of a heart attack the following morning at age 60.

The Aces played on, resolving to pay their own way for however long they stayed alive in that year’s championship cycle. That summer, they took the Spingold. Then, in the fall, they won the international team trials. Once more, the Aces found themselves in a Bermuda Bowl final. Once more, the Italians were waiting.

The Blue Team had long ago disbanded, but Italy was spearheaded by Giorgio Belladonna and Benito Garozzo, the spine of the Blue Team’s success. At 60 and 56, respectively, they were slowing down yet, as Hamman wrote in a post-match editorial for Sports Illustrated, were still “the Ruth and Gehrig of the game.” When they opened play against Wolff and Hamman, it marked the final time the four highest-ranked players in the World Bridge Federation’s career points totals would compete against each other for a world championship.

They battled for the better part of three days, neither side gaining more than a foothold over the other. Finally, the Italians pulled into a narrow lead with four hands remaining, only for the unthinkable to happen: Belladonna made a fatal calculation error with the game in hand—the bridge equivalent of Ruth muffing a fly ball to lose the World Series. Ira’s final team had achieved his final goal. The Italians were defeated.

The Aces disbanded following the win, though the team’s impact ripples through the lives of its members half a century later. Ira plus five of the six original Aces are enshrined in the American Contract Bridge League Hall of Fame (Lawrence chose to decline nomination). Wolff maintains the “Aces on Bridge” column after purchasing it from Ira’s estate. Lawrence blossomed into one of the game’s premier authors and coaches, vocations he first pursued at Ira’s behest. Aces alumni continued to win world championships as late as 2009, when Hamman, now regarded as perhaps the best player of all time, snagged his last Bermuda Bowl shortly after turning 71.

Despite that, the conceit of Ira’s experiment mostly died with him. Countries like Holland and China feature state-sponsored teams, while an Italian squad called Lavazza is backed by a coffee company. But there is no swashbuckling entrepreneur eager to shake up the system. Bridge is aging out, now played by a fraction as many Americans in the 1940s despite the population growing exponentially. The odds of another experiment like the Dallas Aces diminish each passing year, which is sadly fitting. Large men can’t live in shrinking worlds.

Write to [email protected].