This month, a cadre of Dallas’ art world notables will gather for the revealing of the latest recipient of the Nasher Sculpture Center’s Nasher Prize for sculpture. The Nasher Prize, which was launched in 2015, is promoted by the museum as nothing less than “the most significant award in the world dedicated exclusively to contemporary sculpture.” The claim is as ambitious as it is audacious. Perhaps, if there were a new sculpture prize launched by a museum in, say, Athens, Rome, or Florence, whose own civic history bears an outsize relation to the history of sculpture, the world might immediately sit up and take notice. But in Texas, where the cultural soil, however fertile, is shallow, earning that kind of authority requires a certain amount of braggadocio.

In its short history, the Nasher Prize has displayed some tremendous resourcefulness. The museum has tapped a jury of esteemed art world professionals—including heavy hitters like former Tate director and Turner Prize jury chairman Nicholas Serota—to name a recipient. The Nasher Prize Gala, which serves as one of the Nasher’s two primary fundraising events, is the centerpiece of an ever-expanding calendar of lectures, panel discussions, and conversations organized around the prize. The prize has also allowed the museum to leverage new partnerships with big-name institutions and launch new international initiatives far beyond the confines of the Arts District galleries and garden, originally built to house real estate magnate Raymond Nasher and his wife Patsy’s unparalleled collection of modern sculpture.

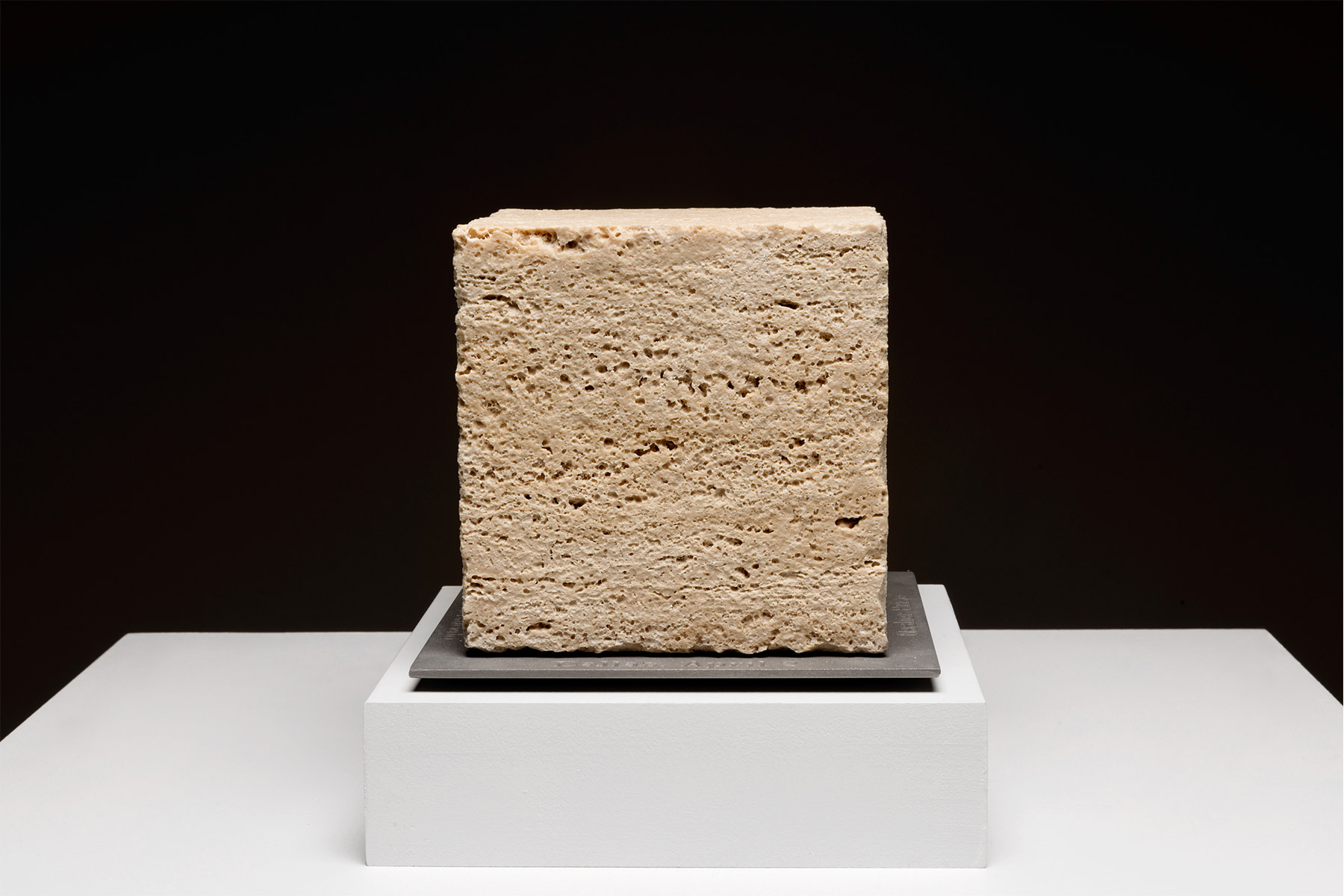

And while there is a growing list of art prizes launched by museums around the world, what makes the Nasher Prize different is its basic conceit. Rather than awarding an up-and-coming artist or honoring the career achievements of a living master, as so many other prizes do, the Nasher Prize has so far focused on artists in their mid- to late careers who jurors determine have “produced a significant body of work that has influenced the understanding of sculpture,” as Nasher director Jeremy Strick puts it. And because sculpture itself has become so broadly defined in contemporary art practice—incorporating everything from found objects to social organizing, immersive installations to virtual reality—the Nasher Prize is set up not only to offer validation to the artists it honors, but to weigh in on the very definition of contemporary sculpture. You might just call it the “not painting prize.”

The first three Nasher Prize laureates have borne out this curatorial logic with seemingly meticulous intent. Doris Salcedo, Pierre Huyghe, and Theaster Gates are notable choices not so much because they are the most important artists working today, but rather because each artist produces work that presents a radically different response to the question of what sculpture is or can be. On the surface, this appears to make the Nasher Prize a compelling commentary on the state of contemporary sculpture, but it is an approach that has also made the prize predictable. As much as its string of laureates asserts a claim on the evolving definition of sculpture, it also demonstrates a tentative or reactionary negotiation on the part of the prize’s jurors of political and cultural currents.

In its first year, the prize had to show that it was not simply another laudatory soapbox for the well-worn tradition of white male object-makers. And so the prize had to go to a woman artist, preferably a woman who was not American or European, whose selection could demonstrate that the institution was going to look outside its own walls and cultural background and engage with social and political issues that resonated with the headlines. But it couldn’t look too far afield. The artist also needed to have a considerable international reputation to demonstrate that the Nasher Prize was awarded to significant contemporary artists. Colombian Doris Salcedo checked all those boxes. Her work, which includes, most famously, hanging chairs of the Palace of Justice in Bogotá to commemorate the 17th anniversary of the siege of the palace by guerrillas, and carving a massive crack into the floor of the Tate Modern’s Turbine Vault, is political in a way that isn’t frightening to Western sensibilities, and object-based in a way that still nods to the legacy of modernism.

With those considerations out of the way, in its second year, the Nasher Prize was free to pick a white European male, but not yet ready to choose someone who simply made sculptural objects. A recipient of the Guggenheim’s Hugo Boss Prize, Pierre Huyghe produces broad works illustrative of the collapsing modes of traditional art-making and the emergence of a performative, interactive approach to art that blurs the distinction between reality and fantasy. Does it matter if Huyghe’s work is considered “sculpture”? Perhaps not. But by awarding him a sculpture prize, the Nasher could demonstrate in its sophomore year that the jury has an appropriately expansive understanding of the medium.

The atmosphere around year three of the prize—deliberations occurred in the wake of the Dallas police shootings—suggested that the jury would give the award to an American artist whose work grappled with the dominant political conversation of the moment. Obvious choices included artists like Rick Lowe and Theaster Gates, who both work in a field known as “socially engaged art” or “social sculpture,” an artistic practice that engages in political and community organizing and social change. You could argue that of the two, Lowe, a 2014 recipient of a MacArthur Genius Award who has received a commission from the Nasher in the past, is the more influential and important of the pair, but Gates received the prize, perhaps because Gates makes more traditional art objects.

This year the Nasher has set itself up to go in two directions. If it continues its continental tour of world artists, perhaps it will turn its attention to Asia, which would fall in line with the prize’s penchant for picking artists whose work responds to topical global political tension. Or, having already checked a handful of political boxes, the prize has set itself up to recalibrate its claim as being the most significant award in contemporary sculpture by being awarded to a more traditional, object-making sculptor. Someone like Rachel Whiteread, whose work is conceptually and politically rigorous and yet is sculpture with a capital S, and who has received multiple exhibitions at Serota’s Tate, may fit the bill.

Regardless of which way the prize goes, the predictability of the logic driving it reveals its shortcomings. Tyler Green is the writer and host of The Modern Art Notes Podcast. On the one hand, he says the Nasher Prize allows the institution to go outside its walls and highlight work that doesn’t “fit [the] traditional white cube bricks-and-mortar box, plus artists who intentionally, self-consciously, and eagerly engage a world beyond the art silo.” But the Nasher Prize also demonstrates an inwardly looking self-consciousness that represents a new kind of art silo.

Is there value in a prize whose primary form of interest may not be the artists it honors but the statement they make collectively about the prize itself, the institution that sponsors it, and the jurors it has tapped to make the selections? In its eagerness to check the right boxes, has the Nasher Prize already become, even in its short history, overly didactic? It is a problem the Nasher Prize shares with the idea of art prizes in general. Their posturing, proselytizing, and proclaiming generally make them less interesting and relevant vehicles of steering conversations around art than what art museums traditionally are designed to do, which is mount exhibitions.

It will be a while before we can really determine whether the Nasher Prize will live up to its billing as the most important prize in contemporary sculpture. Prizes of any significance build their authority and relevance over time. But for Strick, the success of the prize also rests in stirring up these very kinds of questions about whether or not the Nasher Prize has a voice that contributes to our understanding of contemporary art.

“I’d like to see debate about our laureates,” Strick says. “If a publication in Tokyo or Dallas said, ‘This is a great choice,’ or, ‘That choice was terrible.’ If this takes on its own life outside of what we do, that would be, I think, a real sign, an indication of success.”

In its short history, the Nasher Prize has displayed some tremendous resourcefulness. The museum has tapped a jury of esteemed art world professionals—including heavy hitters like former Tate director and Turner Prize jury chairman Nicholas Serota—to name a recipient. The Nasher Prize Gala, which serves as one of the Nasher’s two primary fundraising events, is the centerpiece of an ever-expanding calendar of lectures, panel discussions, and conversations organized around the prize. The prize has also allowed the museum to leverage new partnerships with big-name institutions and launch new international initiatives far beyond the confines of the Arts District galleries and garden, originally built to house real estate magnate Raymond Nasher and his wife Patsy’s unparalleled collection of modern sculpture.

And while there is a growing list of art prizes launched by museums around the world, what makes the Nasher Prize different is its basic conceit. Rather than awarding an up-and-coming artist or honoring the career achievements of a living master, as so many other prizes do, the Nasher Prize has so far focused on artists in their mid- to late careers who jurors determine have “produced a significant body of work that has influenced the understanding of sculpture,” as Nasher director Jeremy Strick puts it. And because sculpture itself has become so broadly defined in contemporary art practice—incorporating everything from found objects to social organizing, immersive installations to virtual reality—the Nasher Prize is set up not only to offer validation to the artists it honors, but to weigh in on the very definition of contemporary sculpture. You might just call it the “not painting prize.”

The Nasher Prize is set up not only to offer validation to the artists it honors, but to weigh in on the very definition of contemporary sculpture.

The first three Nasher Prize laureates have borne out this curatorial logic with seemingly meticulous intent. Doris Salcedo, Pierre Huyghe, and Theaster Gates are notable choices not so much because they are the most important artists working today, but rather because each artist produces work that presents a radically different response to the question of what sculpture is or can be. On the surface, this appears to make the Nasher Prize a compelling commentary on the state of contemporary sculpture, but it is an approach that has also made the prize predictable. As much as its string of laureates asserts a claim on the evolving definition of sculpture, it also demonstrates a tentative or reactionary negotiation on the part of the prize’s jurors of political and cultural currents.

In its first year, the prize had to show that it was not simply another laudatory soapbox for the well-worn tradition of white male object-makers. And so the prize had to go to a woman artist, preferably a woman who was not American or European, whose selection could demonstrate that the institution was going to look outside its own walls and cultural background and engage with social and political issues that resonated with the headlines. But it couldn’t look too far afield. The artist also needed to have a considerable international reputation to demonstrate that the Nasher Prize was awarded to significant contemporary artists. Colombian Doris Salcedo checked all those boxes. Her work, which includes, most famously, hanging chairs of the Palace of Justice in Bogotá to commemorate the 17th anniversary of the siege of the palace by guerrillas, and carving a massive crack into the floor of the Tate Modern’s Turbine Vault, is political in a way that isn’t frightening to Western sensibilities, and object-based in a way that still nods to the legacy of modernism.

With those considerations out of the way, in its second year, the Nasher Prize was free to pick a white European male, but not yet ready to choose someone who simply made sculptural objects. A recipient of the Guggenheim’s Hugo Boss Prize, Pierre Huyghe produces broad works illustrative of the collapsing modes of traditional art-making and the emergence of a performative, interactive approach to art that blurs the distinction between reality and fantasy. Does it matter if Huyghe’s work is considered “sculpture”? Perhaps not. But by awarding him a sculpture prize, the Nasher could demonstrate in its sophomore year that the jury has an appropriately expansive understanding of the medium.

The atmosphere around year three of the prize—deliberations occurred in the wake of the Dallas police shootings—suggested that the jury would give the award to an American artist whose work grappled with the dominant political conversation of the moment. Obvious choices included artists like Rick Lowe and Theaster Gates, who both work in a field known as “socially engaged art” or “social sculpture,” an artistic practice that engages in political and community organizing and social change. You could argue that of the two, Lowe, a 2014 recipient of a MacArthur Genius Award who has received a commission from the Nasher in the past, is the more influential and important of the pair, but Gates received the prize, perhaps because Gates makes more traditional art objects.

This year the Nasher has set itself up to go in two directions. If it continues its continental tour of world artists, perhaps it will turn its attention to Asia, which would fall in line with the prize’s penchant for picking artists whose work responds to topical global political tension. Or, having already checked a handful of political boxes, the prize has set itself up to recalibrate its claim as being the most significant award in contemporary sculpture by being awarded to a more traditional, object-making sculptor. Someone like Rachel Whiteread, whose work is conceptually and politically rigorous and yet is sculpture with a capital S, and who has received multiple exhibitions at Serota’s Tate, may fit the bill.

Regardless of which way the prize goes, the predictability of the logic driving it reveals its shortcomings. Tyler Green is the writer and host of The Modern Art Notes Podcast. On the one hand, he says the Nasher Prize allows the institution to go outside its walls and highlight work that doesn’t “fit [the] traditional white cube bricks-and-mortar box, plus artists who intentionally, self-consciously, and eagerly engage a world beyond the art silo.” But the Nasher Prize also demonstrates an inwardly looking self-consciousness that represents a new kind of art silo.

Is there value in a prize whose primary form of interest may not be the artists it honors but the statement they make collectively about the prize itself, the institution that sponsors it, and the jurors it has tapped to make the selections? In its eagerness to check the right boxes, has the Nasher Prize already become, even in its short history, overly didactic? It is a problem the Nasher Prize shares with the idea of art prizes in general. Their posturing, proselytizing, and proclaiming generally make them less interesting and relevant vehicles of steering conversations around art than what art museums traditionally are designed to do, which is mount exhibitions.

It will be a while before we can really determine whether the Nasher Prize will live up to its billing as the most important prize in contemporary sculpture. Prizes of any significance build their authority and relevance over time. But for Strick, the success of the prize also rests in stirring up these very kinds of questions about whether or not the Nasher Prize has a voice that contributes to our understanding of contemporary art.

“I’d like to see debate about our laureates,” Strick says. “If a publication in Tokyo or Dallas said, ‘This is a great choice,’ or, ‘That choice was terrible.’ If this takes on its own life outside of what we do, that would be, I think, a real sign, an indication of success.”

Get the FrontRow Newsletter

Get a front row seat to the best shows, arts, and things to do across North Texas. Never miss a beat.