Over the course of yet another summer in which the local sports media spooned out ample daily portions of watered-down, lukewarm porridge in its relentless pursuit of nonevents, one story of interest managed, albeit briefly, to emerge. An assemblage of distinguished names from the Dallas Cowboys’ hallowed past—Troy Aikman, Tony Dorsett, Roger Staubach, Bob Lilly—has embarked on a public relations blitzkrieg, orchestrated by longtime lever-puller Lisa LeMaster, to place Clint Murchison Jr. into consideration for posthumous induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Not many of even the most ardent followers of the team actually know who Murchison was. He essentially created the franchise that began on-the-field operations in 1960. And not all that many pro football devotees knew who he was then, either. In direct contrast to the bombastic proclivities of our present-day franchise owners, Murchison relegated himself to life in the shadows.

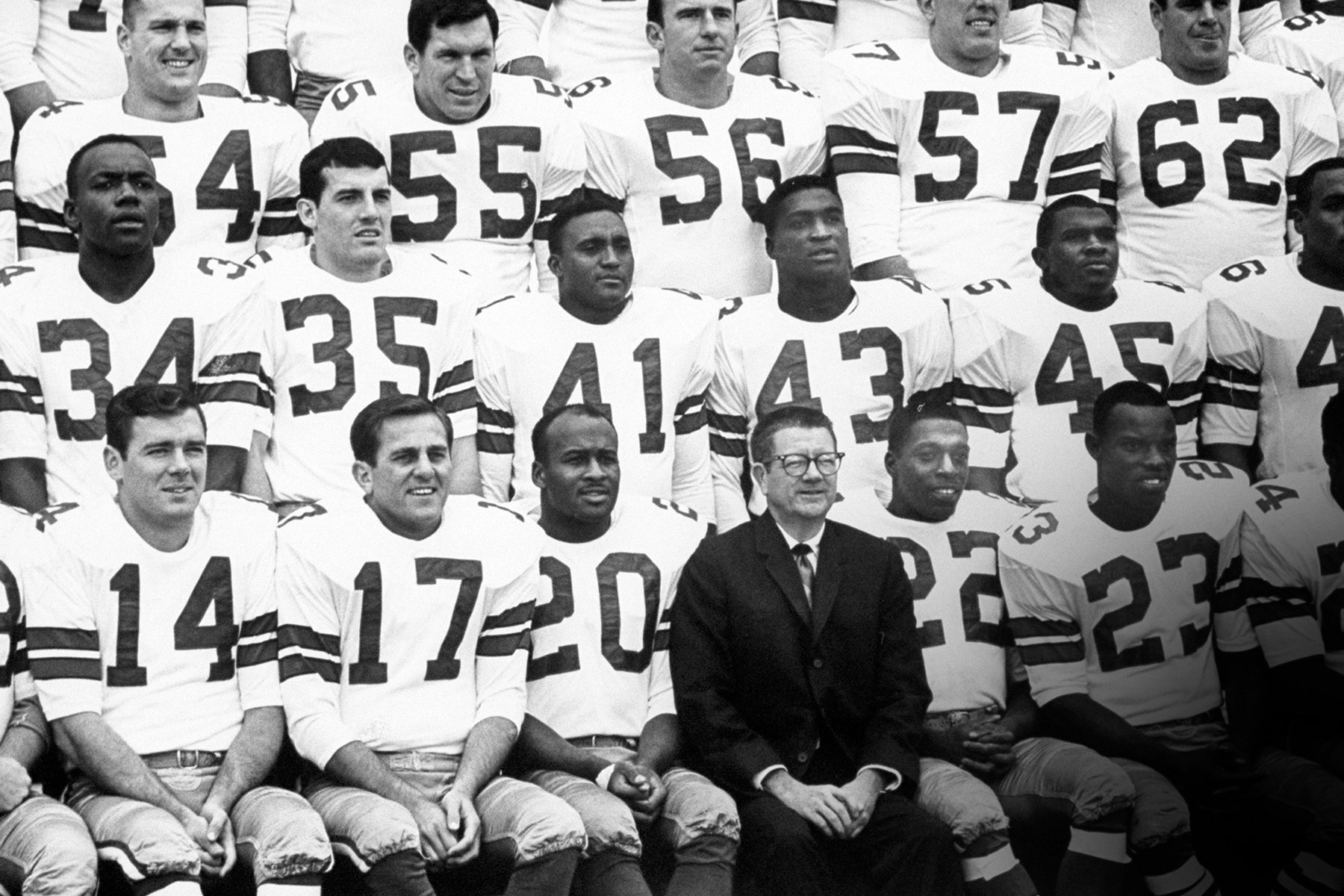

He was ranked among the original oil-y-garchs who truly ruled the Texas economic landscape of his time. Ever the dichotomy, Murchison did not look nor act the part of the stereotypical Lone Star petroleum magnates of that era. With his crew cut and horn-rimmed glasses, he cultivated the classic dweeb look that had been stylish during the 1950s. “He seemed withdrawn to those who did not know him well,” says a noted historian of the Dallas societal tapestry (who asked not to be named). “He was not a people person. He came across as almost autistic. He was an odd, odd, odd guy.”

If that were the case, Murchison’s introversion perhaps could be attributed to the fact that there were few among his peer group who could discuss the higher aspects of abstract mathematics mostly understood only to big brains with Germanic surnames. In his younger days, Murchison was a Phi Beta Kappa in electrical engineering at Duke University and capped that off with a master’s degree in mathematics from MIT. He could easily have been accused of possessing a four-digit IQ. Those abilities were transposed into the simplest of formulas to achieve success in business. When it comes to management, less is more. That principle was applied to a varied range of operations that included insurance, real estate, the Del Mar thoroughbred racetrack in California, and a taxicab company, among other entities that encompassed a financial powerhouse described by lawyer Philip Palmer Jr. as “obscure, fantastic, and phantasmagorical.”

In establishing the blueprint for the Cowboys organization, Murchison hired Tex Schramm to general manage and Tom Landry to coach. Then, with the passage of time, Murchison sat quietly backstage and watched as his team evolved into the behemoth that rivaled the New York Yankees as the absolute potentates of professional sports in America. He emerged from seclusion to visit the team’s media headquarters in Miami on the occasion of Super Bowl X and performed a rousing duet version of “Beautiful, Beautiful Texas” with Sen. John Tower before retreating back into his cavern of privacy to rarely be seen in public again. He died of a neurological disorder at age 63 in 1987, a couple of years after selling the team—for $80 million, then the most ever paid for a sports franchise—in the midst of the collapse of the oil and real estate markets.

Given Murchison’s unmistakable role in the establishment of the Cowboys and the part that the team played in the NFL’s ascendancy to the pinnacle of the modern entertainment industry, it is plain that the man merits consideration for the Hall of Fame. As that situation plays out, though, it may give rise to another aspect of Murchison’s unique life and career that, if not unknown to the prying eyes and ears of the local media, was certainly unreported. In short: he was a dirty businessman and degenerate gambler.

“In a report of an investigation being conducted by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms of the Department of the Treasury, special agents had learned ‘that [Clint] Murchison was “fronting” for [organized crime] out of Florida at Tony Roma’s Place for Ribs in Dallas.’ The ATF reported that ‘Murchison is indeed partners with Tony Roma, real name Anthony LoPresti, and past manager of Playboy Clubs in Chicago and Montreal, Canada.’ Roma had been registered at Acapulco Towers at the same time that the 1970 mobster conference was being held there. The report also linked Murchison with Ettore Zappi, a capo in the Carlo Gambino crime family in New York.

‘From the data presently available,’ the ATF concluded, ‘it appears that Murchison is firmly entrenched with individuals who are proven national Mafia figures.’ Murchison’s name was also dragged into a major financial scam in which $2 million in Teamsters insurance premiums were diverted to several organized-crime operations. Among those insurance companies implicated in the scheme was National American Life Insurance Company. The owner of the firm was a close business associate of Carlos Marcello.”

Those few paragraphs appear in a book, Interference: How Organized Crime Influences Professional Football, written by Dan E. Moldea and published in 1989 by William Morrow and Company. The book lays out that Murchison was investigated by nine federal agencies and two congressional committees. He had multiple business partnerships with associates of Carlos Marcello, the “most feared Mafia boss in the South.” On a weekly basis, he bet tens of thousands of dollars on sports, including the NFL, with Gilbert “The Brain” Beckley, one of the biggest bookmakers in the country. Moldea’s book further alleges that Murchison maintained a working relationship with former U.S. Senate power broker Bobby Baker (known as “Lyndon Jr.” for his close affiliation with the president), who was sent to prison in 1967 on seven counts of fraud, grand larceny, and tax evasion.

Moldea wrote: “Murchison was questioned by a U.S. Senate committee about his relationship with Baker, particularly after federal investigators discovered that Murchison paid for Washington parties thrown by Baker, who had arranged dates between Capitol Hill women and wealthy businessmen. … After Murchison failed to win approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to import products from his Haitian meat-packing business in Port-au-Prince, Baker intervened on Murchison’s behalf and received the necessary FDA approval.” (This is the same Bobby Baker who claimed John F. Kennedy said to him, “Any day I don’t get a strange piece of ass I have a migraine headache.”)

Despite the florid nature of these allegations, Murchison serves as nothing more than a bit player in Moldea’s 512-page book. Interference throughout presents the NFL as a historically corrupt organization since its outset, rife with point-shaving, rigged games, and a generous cast of famous personalities motivated by shady and dubious instincts. Moldea is 68, lives in Washington, D.C., and continues to write.

“The NFL book was written so long ago, I don’t remember anything it might have had to say about Clint Murchison,” Moldea told me in July. He does recall, though, that it received an unwelcome response from reviewers and mainstream sports journalists, who he insists enjoy a happy symbiotic arrangement with the league and its hierarchy. “It hardly made me popular with my sports colleagues. I was treated like a bastard son at a family reunion,” he says. The deepest stab resulted from what Moldea describes as “a lying review” printed in the New York Times.

“The person who wrote the review, Gerald Eskenazi, is a respected sports journalist,” Moldea says. “I knew him. In the review he ripped me for not having information in the book that was, in fact, in there, and for having information in the book that should not have been that wasn’t in there. I called him and requested a retraction. He said he couldn’t do that. I asked if the paper would publish a letter to the editor that I would write and was told that was out of the question, too. So I sued the New York Times. That lawsuit went on longer than World War II. I won, and then lost after a federal appeals court reversed a ruling that had originally been in my favor.” After the Times, he says, sales of his book “nose-dived.” Regarding its content, he stands by every word. “I was never sued, or threatened with a lawsuit,” Moldea says. Prior to publication, he forwarded his manuscript to the NFL requesting comment. The league, he says, never responded.

Regarding the Murchison Hall of Fame bid, he says he wishes that well, noting that the Cowboys’ founder comes across as an Eagle Scout when compared with material that he published about Wellington Mara, Charles Bidwill, Art Rooney, and other owners who are in the Hall of Fame.

Should the league eventually install Clint Murchison Jr. in its shrine, perhaps Jerry Jones might be inspired to place him in the Cowboys’ Ring of Honor. In any case, now that the Supreme Court has opened the door to legalized sports betting, Murchison has proven himself to be a man ahead of his time.

Not many of even the most ardent followers of the team actually know who Murchison was. He essentially created the franchise that began on-the-field operations in 1960. And not all that many pro football devotees knew who he was then, either. In direct contrast to the bombastic proclivities of our present-day franchise owners, Murchison relegated himself to life in the shadows.

He was ranked among the original oil-y-garchs who truly ruled the Texas economic landscape of his time. Ever the dichotomy, Murchison did not look nor act the part of the stereotypical Lone Star petroleum magnates of that era. With his crew cut and horn-rimmed glasses, he cultivated the classic dweeb look that had been stylish during the 1950s. “He seemed withdrawn to those who did not know him well,” says a noted historian of the Dallas societal tapestry (who asked not to be named). “He was not a people person. He came across as almost autistic. He was an odd, odd, odd guy.”

If that were the case, Murchison’s introversion perhaps could be attributed to the fact that there were few among his peer group who could discuss the higher aspects of abstract mathematics mostly understood only to big brains with Germanic surnames. In his younger days, Murchison was a Phi Beta Kappa in electrical engineering at Duke University and capped that off with a master’s degree in mathematics from MIT. He could easily have been accused of possessing a four-digit IQ. Those abilities were transposed into the simplest of formulas to achieve success in business. When it comes to management, less is more. That principle was applied to a varied range of operations that included insurance, real estate, the Del Mar thoroughbred racetrack in California, and a taxicab company, among other entities that encompassed a financial powerhouse described by lawyer Philip Palmer Jr. as “obscure, fantastic, and phantasmagorical.”

He had multiple business partnerships with associates of Carlos Marcello, the “most feared Mafia boss in the South.” On a weekly basis, he bet tens of thousands of dollars on sports, including the NFL.

In establishing the blueprint for the Cowboys organization, Murchison hired Tex Schramm to general manage and Tom Landry to coach. Then, with the passage of time, Murchison sat quietly backstage and watched as his team evolved into the behemoth that rivaled the New York Yankees as the absolute potentates of professional sports in America. He emerged from seclusion to visit the team’s media headquarters in Miami on the occasion of Super Bowl X and performed a rousing duet version of “Beautiful, Beautiful Texas” with Sen. John Tower before retreating back into his cavern of privacy to rarely be seen in public again. He died of a neurological disorder at age 63 in 1987, a couple of years after selling the team—for $80 million, then the most ever paid for a sports franchise—in the midst of the collapse of the oil and real estate markets.

Given Murchison’s unmistakable role in the establishment of the Cowboys and the part that the team played in the NFL’s ascendancy to the pinnacle of the modern entertainment industry, it is plain that the man merits consideration for the Hall of Fame. As that situation plays out, though, it may give rise to another aspect of Murchison’s unique life and career that, if not unknown to the prying eyes and ears of the local media, was certainly unreported. In short: he was a dirty businessman and degenerate gambler.

“In a report of an investigation being conducted by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms of the Department of the Treasury, special agents had learned ‘that [Clint] Murchison was “fronting” for [organized crime] out of Florida at Tony Roma’s Place for Ribs in Dallas.’ The ATF reported that ‘Murchison is indeed partners with Tony Roma, real name Anthony LoPresti, and past manager of Playboy Clubs in Chicago and Montreal, Canada.’ Roma had been registered at Acapulco Towers at the same time that the 1970 mobster conference was being held there. The report also linked Murchison with Ettore Zappi, a capo in the Carlo Gambino crime family in New York.

‘From the data presently available,’ the ATF concluded, ‘it appears that Murchison is firmly entrenched with individuals who are proven national Mafia figures.’ Murchison’s name was also dragged into a major financial scam in which $2 million in Teamsters insurance premiums were diverted to several organized-crime operations. Among those insurance companies implicated in the scheme was National American Life Insurance Company. The owner of the firm was a close business associate of Carlos Marcello.”

Those few paragraphs appear in a book, Interference: How Organized Crime Influences Professional Football, written by Dan E. Moldea and published in 1989 by William Morrow and Company. The book lays out that Murchison was investigated by nine federal agencies and two congressional committees. He had multiple business partnerships with associates of Carlos Marcello, the “most feared Mafia boss in the South.” On a weekly basis, he bet tens of thousands of dollars on sports, including the NFL, with Gilbert “The Brain” Beckley, one of the biggest bookmakers in the country. Moldea’s book further alleges that Murchison maintained a working relationship with former U.S. Senate power broker Bobby Baker (known as “Lyndon Jr.” for his close affiliation with the president), who was sent to prison in 1967 on seven counts of fraud, grand larceny, and tax evasion.

Moldea wrote: “Murchison was questioned by a U.S. Senate committee about his relationship with Baker, particularly after federal investigators discovered that Murchison paid for Washington parties thrown by Baker, who had arranged dates between Capitol Hill women and wealthy businessmen. … After Murchison failed to win approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to import products from his Haitian meat-packing business in Port-au-Prince, Baker intervened on Murchison’s behalf and received the necessary FDA approval.” (This is the same Bobby Baker who claimed John F. Kennedy said to him, “Any day I don’t get a strange piece of ass I have a migraine headache.”)

Despite the florid nature of these allegations, Murchison serves as nothing more than a bit player in Moldea’s 512-page book. Interference throughout presents the NFL as a historically corrupt organization since its outset, rife with point-shaving, rigged games, and a generous cast of famous personalities motivated by shady and dubious instincts. Moldea is 68, lives in Washington, D.C., and continues to write.

“The NFL book was written so long ago, I don’t remember anything it might have had to say about Clint Murchison,” Moldea told me in July. He does recall, though, that it received an unwelcome response from reviewers and mainstream sports journalists, who he insists enjoy a happy symbiotic arrangement with the league and its hierarchy. “It hardly made me popular with my sports colleagues. I was treated like a bastard son at a family reunion,” he says. The deepest stab resulted from what Moldea describes as “a lying review” printed in the New York Times.

“The person who wrote the review, Gerald Eskenazi, is a respected sports journalist,” Moldea says. “I knew him. In the review he ripped me for not having information in the book that was, in fact, in there, and for having information in the book that should not have been that wasn’t in there. I called him and requested a retraction. He said he couldn’t do that. I asked if the paper would publish a letter to the editor that I would write and was told that was out of the question, too. So I sued the New York Times. That lawsuit went on longer than World War II. I won, and then lost after a federal appeals court reversed a ruling that had originally been in my favor.” After the Times, he says, sales of his book “nose-dived.” Regarding its content, he stands by every word. “I was never sued, or threatened with a lawsuit,” Moldea says. Prior to publication, he forwarded his manuscript to the NFL requesting comment. The league, he says, never responded.

Regarding the Murchison Hall of Fame bid, he says he wishes that well, noting that the Cowboys’ founder comes across as an Eagle Scout when compared with material that he published about Wellington Mara, Charles Bidwill, Art Rooney, and other owners who are in the Hall of Fame.

Should the league eventually install Clint Murchison Jr. in its shrine, perhaps Jerry Jones might be inspired to place him in the Cowboys’ Ring of Honor. In any case, now that the Supreme Court has opened the door to legalized sports betting, Murchison has proven himself to be a man ahead of his time.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Dallas’ most important news stories of the week, delivered to your inbox each Sunday.