Beginning in the early 1830s, when James Bowie built a cotton mill in what would a few years later become the Republic of Texas, that industry grew into the state’s largest cash crop, annually supplying 25 percent of the country’s cotton needs. By the second decade of the 20th century, there was no doubt that cotton was truly king; Dallas was its palace and the Dallas Cotton Exchange considered its throne. The 17-story building, on the corner of North St. Paul and San Jacinto streets, housed buyers and brokers who daily transacted more business than similar exchanges did in Memphis and New York City.

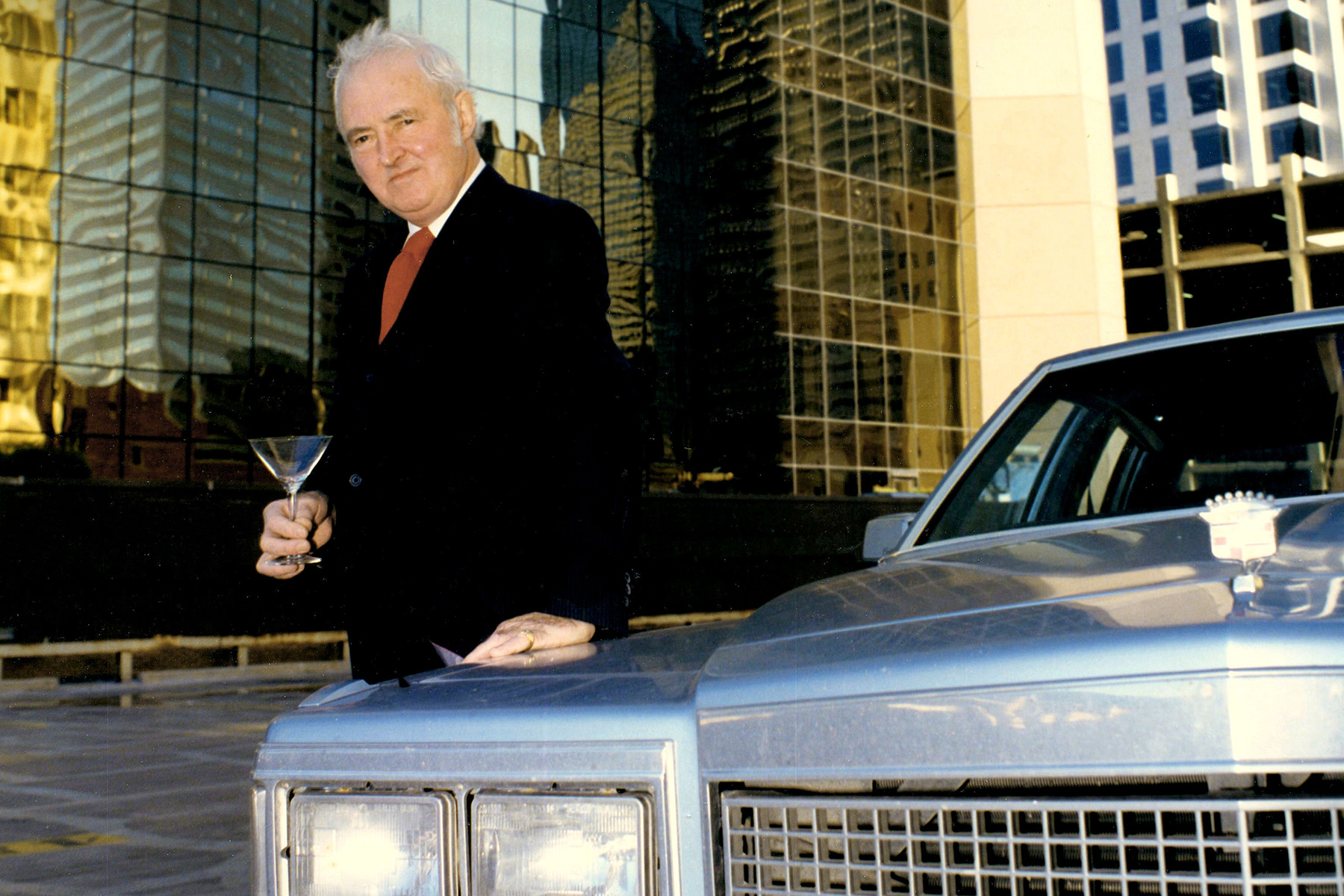

But in the 1950s and 1960s, the cotton industry and its related textile and apparel manufacturing businesses in Texas were in turmoil, threatened by the increased importation of cheaply made foreign fabrics, mill closings by independent owners, renewed activity by mills in New England and the Southeast, and the rise of synthetic textiles. And then, in the late 1970s, a 56-year-old Englishman with more than 30 years in the cotton business decided to move to the United States. Realizing Texas’ importance in the industry and with encouragement from friends in Dallas, he moved into an office at the Dallas Cotton Exchange. He was optimistic that new ways of doing business, tricks he’d learned in markets around the world, would improve their fortunes.

My introduction to this man came as I entered a store in Highland Park Village some years later. I was met at the door by an employee—nicely dressed and smiling, ruddy complexioned, older—who greeted me in a proper English accent. I got the impression that he was not your typical retail employee. So when he and I left the store at the same time, and he invited me to have a cup of coffee a few doors down because his wife had been held up and wouldn’t be joining him, I accepted.

His name was Dennis Gordon King, and I was right in my assessment of him. The job where I had met him was his way of staying busy in retirement. We didn’t talk long, but Dennis did mention that he’d spent his life in the cotton industry, and I told him my family had been in the textile business until the late ’60s. I was delighted when he invited me to visit his home the following weekend to continue the conversation and meet his wife, Patricia, also newly retired from a position with one of Dallas’ large venture capital firms.

It turned out that the small rental close to SMU where I lived was actually just a few blocks from the home Dennis and his wife shared. I spent a lazy Saturday afternoon on their couch with a cold libation or two while he smoked a cigar and sipped his Scotch, telling me wonderful stories of his growing up in the 1920s in Lancashire, England. His family had been involved in the cotton industry since 1897, when the King Mill Limited was formed in Royton, Lancashire.

He was proud of his military career, and he spoke of that first. With the war delaying his entry into the family business, he joined the British military at age 17 and was sent to the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst. Three months later, as an 18-year-old newly commissioned lieutenant, he became a squadron tank commander in the 7th Armoured Division, known forever as the legendary Desert Rats that battled Rommel in North Africa.

After the desert campaign, where he suffered several leg injuries when his tank took a direct hit, he took part in the Allied invasion of Italy, and on D Day, June 6, 1944, he led the third wave of tanks onto Gold Beach in Normandy. Dennis was highly decorated from his campaigns in Egypt, Sicily, Italy, Normandy, and New Guinea. With Sir Winston Churchill looking on, in 1944, he was awarded the Military Cross, England’s second-highest military honor, by King George VI.

In 1947, Dennis received an honorable discharge with the rank of major. He was offered a position with the Raw Cotton Commission in Liverpool, where he spent time on the docks swapping stories with his good friend Jim McCartney. McCartney had a young son at home named Paul who would eventually meet three other musically inclined youngsters from that area and go on to form a band that invaded the United States.

Dennis was one of six war veterans sent to the United States in 1948 on a Fulbright scholarship to learn the cotton industry; first at Texas A&M University and later at UCLA. The Memphis-based cotton brokerage firm Edward T. Roberts then assigned him to head up its office in Ghent, Belgium. He lived there with his first wife, Doreen, and their children for 30 years, with his work sending him all over the world, buying and selling cotton in Uganda, Bolivia, Spain, Syria, Japan, and elsewhere.

Aside from dealing with cotton growers, buyers, and sellers in foreign countries, he also cultivated contacts in the States. He primarily focused on cotton’s citadel—Dallas—and the large milling and apparel manufacturing operations here, among them Burlington Industries of North Carolina (which had bought two milling operations near Dallas), Conro Manufacturing on North Good Street, and Texas Textile Mills, the state’s largest.

Finally arriving in Dallas and taking an office at the Cotton Exchange, he found people here receptive to trying different business strategies. Dennis told me about a few of the problems some were having, and an important one seemed to be their trouble negotiating with new accounts at certain foreign ports. With cotton pricing based on weight, he encouraged them to utilize a lower figure that would be quickly acceptable to the buyer. What a few brokers didn’t realize was that when a ship passed through areas with high humidity, the cotton could take on enough moisture to bring about a several percent increase in the load, making up the difference that extended negotiations may not have produced in a sale in the first place.

Dennis also encouraged his fellow brokers to do as he did: go get their hands dirty. Visit with the growers, tour the mills, meet the people in the business who maybe they had only talked to on the phone. A person close to him told me he was so knowledgeable about the business that when visiting a cotton-growing operation anywhere in the world, he could handle and examine a boll for a few seconds and then make a deal with a set price right then and there.

King’s dedication to boosting the fortunes of Dallas’ cotton merchants did help the people doing business here. Eventually, though, more high-tech firms and Fortune 500 companies were moving in, and, with the decentralization of the cotton brokerage business, the importance of cotton in Dallas’ economy shrank. The Dallas Cotton Exchange began emptying out as computers let brokers work from smaller, newer offices, even from one’s kitchen table.

Dennis saw it coming, and, after more than 50 years in the cotton business, he figured he had done all he could do. He closed up his office, locked the door, and pocketed the keys for the last time. Built in 1926, the Cotton Exchange was still beautiful on the outside, but it was inefficient to heat and cool. On the inside, it felt its age. The building was brought down by implosion on June 25, 1994.

In his retirement, Dennis could now spend more time on the golf course. He was a scratch golfer and had more than 100 trophies and a membership in the beautiful Royal Latem Golf Club in Belgium. He continued with his passion after moving to Dallas, spending many weekends playing with co-workers and industry CEOs alike on local courses. With the same energy as a much younger person and not content to settle into his La-Z-Boy with TV remote in hand, he instead took that position as a store greeter, where I had first met him.

A few years later, after I’d moved out of state due to work and lost contact with Dennis, I heard the news of his passing. He died in May 2015, at age 90.

I miss his smile and laughter as he recounted his life and the many stories it could tell. The role he played to expand and grow Dallas’ hierarchy in the business of cotton while simultaneously trying to cut costs that could ultimately affect the consumer hopefully will be appreciated by historians studying the contributions that came out of that venerable old building by its inhabitants. Dennis Gordon King led a life that sounds like the plot of a movie. From tank battles in North African deserts to cotton deals in the heart of Dallas, he was a witness to history. We can only imagine.

But in the 1950s and 1960s, the cotton industry and its related textile and apparel manufacturing businesses in Texas were in turmoil, threatened by the increased importation of cheaply made foreign fabrics, mill closings by independent owners, renewed activity by mills in New England and the Southeast, and the rise of synthetic textiles. And then, in the late 1970s, a 56-year-old Englishman with more than 30 years in the cotton business decided to move to the United States. Realizing Texas’ importance in the industry and with encouragement from friends in Dallas, he moved into an office at the Dallas Cotton Exchange. He was optimistic that new ways of doing business, tricks he’d learned in markets around the world, would improve their fortunes.

My introduction to this man came as I entered a store in Highland Park Village some years later. I was met at the door by an employee—nicely dressed and smiling, ruddy complexioned, older—who greeted me in a proper English accent. I got the impression that he was not your typical retail employee. So when he and I left the store at the same time, and he invited me to have a cup of coffee a few doors down because his wife had been held up and wouldn’t be joining him, I accepted.

His name was Dennis Gordon King, and I was right in my assessment of him. The job where I had met him was his way of staying busy in retirement. We didn’t talk long, but Dennis did mention that he’d spent his life in the cotton industry, and I told him my family had been in the textile business until the late ’60s. I was delighted when he invited me to visit his home the following weekend to continue the conversation and meet his wife, Patricia, also newly retired from a position with one of Dallas’ large venture capital firms.

It turned out that the small rental close to SMU where I lived was actually just a few blocks from the home Dennis and his wife shared. I spent a lazy Saturday afternoon on their couch with a cold libation or two while he smoked a cigar and sipped his Scotch, telling me wonderful stories of his growing up in the 1920s in Lancashire, England. His family had been involved in the cotton industry since 1897, when the King Mill Limited was formed in Royton, Lancashire.

He was proud of his military career, and he spoke of that first. With the war delaying his entry into the family business, he joined the British military at age 17 and was sent to the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst. Three months later, as an 18-year-old newly commissioned lieutenant, he became a squadron tank commander in the 7th Armoured Division, known forever as the legendary Desert Rats that battled Rommel in North Africa.

After the desert campaign, where he suffered several leg injuries when his tank took a direct hit, he took part in the Allied invasion of Italy, and on D Day, June 6, 1944, he led the third wave of tanks onto Gold Beach in Normandy. Dennis was highly decorated from his campaigns in Egypt, Sicily, Italy, Normandy, and New Guinea. With Sir Winston Churchill looking on, in 1944, he was awarded the Military Cross, England’s second-highest military honor, by King George VI.

In 1947, Dennis received an honorable discharge with the rank of major. He was offered a position with the Raw Cotton Commission in Liverpool, where he spent time on the docks swapping stories with his good friend Jim McCartney. McCartney had a young son at home named Paul who would eventually meet three other musically inclined youngsters from that area and go on to form a band that invaded the United States.

Dennis was one of six war veterans sent to the United States in 1948 on a Fulbright scholarship to learn the cotton industry; first at Texas A&M University and later at UCLA. The Memphis-based cotton brokerage firm Edward T. Roberts then assigned him to head up its office in Ghent, Belgium. He lived there with his first wife, Doreen, and their children for 30 years, with his work sending him all over the world, buying and selling cotton in Uganda, Bolivia, Spain, Syria, Japan, and elsewhere.

Dennis also encouraged his fellow brokers to do as he did: go get their hands dirty. Visit with the growers, tour the mills, meet the people in the business.

Aside from dealing with cotton growers, buyers, and sellers in foreign countries, he also cultivated contacts in the States. He primarily focused on cotton’s citadel—Dallas—and the large milling and apparel manufacturing operations here, among them Burlington Industries of North Carolina (which had bought two milling operations near Dallas), Conro Manufacturing on North Good Street, and Texas Textile Mills, the state’s largest.

Finally arriving in Dallas and taking an office at the Cotton Exchange, he found people here receptive to trying different business strategies. Dennis told me about a few of the problems some were having, and an important one seemed to be their trouble negotiating with new accounts at certain foreign ports. With cotton pricing based on weight, he encouraged them to utilize a lower figure that would be quickly acceptable to the buyer. What a few brokers didn’t realize was that when a ship passed through areas with high humidity, the cotton could take on enough moisture to bring about a several percent increase in the load, making up the difference that extended negotiations may not have produced in a sale in the first place.

Dennis also encouraged his fellow brokers to do as he did: go get their hands dirty. Visit with the growers, tour the mills, meet the people in the business who maybe they had only talked to on the phone. A person close to him told me he was so knowledgeable about the business that when visiting a cotton-growing operation anywhere in the world, he could handle and examine a boll for a few seconds and then make a deal with a set price right then and there.

King’s dedication to boosting the fortunes of Dallas’ cotton merchants did help the people doing business here. Eventually, though, more high-tech firms and Fortune 500 companies were moving in, and, with the decentralization of the cotton brokerage business, the importance of cotton in Dallas’ economy shrank. The Dallas Cotton Exchange began emptying out as computers let brokers work from smaller, newer offices, even from one’s kitchen table.

Dennis saw it coming, and, after more than 50 years in the cotton business, he figured he had done all he could do. He closed up his office, locked the door, and pocketed the keys for the last time. Built in 1926, the Cotton Exchange was still beautiful on the outside, but it was inefficient to heat and cool. On the inside, it felt its age. The building was brought down by implosion on June 25, 1994.

In his retirement, Dennis could now spend more time on the golf course. He was a scratch golfer and had more than 100 trophies and a membership in the beautiful Royal Latem Golf Club in Belgium. He continued with his passion after moving to Dallas, spending many weekends playing with co-workers and industry CEOs alike on local courses. With the same energy as a much younger person and not content to settle into his La-Z-Boy with TV remote in hand, he instead took that position as a store greeter, where I had first met him.

A few years later, after I’d moved out of state due to work and lost contact with Dennis, I heard the news of his passing. He died in May 2015, at age 90.

I miss his smile and laughter as he recounted his life and the many stories it could tell. The role he played to expand and grow Dallas’ hierarchy in the business of cotton while simultaneously trying to cut costs that could ultimately affect the consumer hopefully will be appreciated by historians studying the contributions that came out of that venerable old building by its inhabitants. Dennis Gordon King led a life that sounds like the plot of a movie. From tank battles in North African deserts to cotton deals in the heart of Dallas, he was a witness to history. We can only imagine.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Dallas’ most important news stories of the week, delivered to your inbox each Sunday.