Imagine your grandmother sitting in her favorite chair as she stares at footage of a burning New York City. An authoritative voice-over from a former government official brings a dire warning: “It could be just a matter of time before a major attack may happen on U.S. soil again.”

Philip Diehl is telling your grandmother she needs to be prepared. When that attack comes, everything could change, and she’d better have some gold. Diehl, who was born in Dallas, was the 35th director of the U.S. Mint, a job he left in 2000. Now he is the president of something called U.S. Money Reserve. The former is one of the oldest agencies in the federal government. The latter, in tiny type at the bottom of its website, disclaims: “Not affiliated with the U.S. government and the U.S. Mint.”

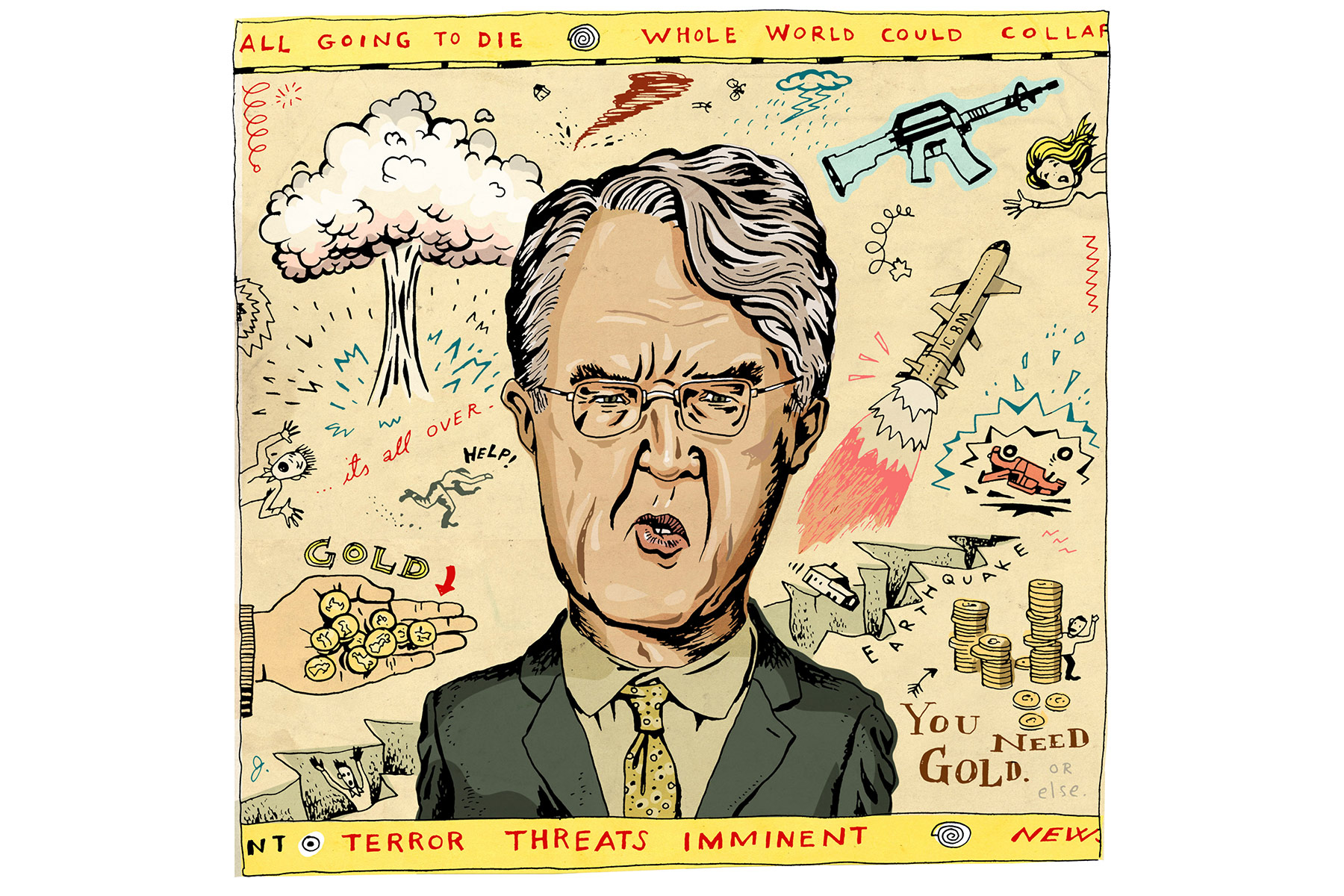

The threat of a terrorist attack is part of a two-minute infomercial uploaded to YouTube in October 2017 that also features images of a man wearing a Middle Eastern headdress, his face hidden, holding an assault rifle above his head; a mushroom cloud from a nuclear explosion; and graphs depicting a stock market crash as the result of “cyberthieves, bank failures, and national debt.” It is all set in the context of a staged press conference, with Diehl standing at a podium, facing a gallery of fake reporters. Behind Diehl is a vault, guarded by fake cops. Off to the side, there are real American flags. One final detail: Diehl’s podium bears a seal, the bottom half of which is obscured by a caption displaying the phone number for U.S. Money Reserve and the message “America in crisis mode.” The top half of the seal, the only part visible, says “U.S. Mint Director.”

Perhaps it was this specific video that convinced an elderly member of a prominent Dallas family to pay six figures to U.S. Money Reserve for some gold coins. Bruce Steckler, a Dallas-based lawyer who represented that family, has met or represented people from here and elsewhere who have bought as much as half a million dollars in gold from the Austin-based company. According to Steckler, what they ended up with was not worth what they paid.

It all started for Steckler a few years ago when his wife’s college roommate called him out of the blue. Her elderly mother-in-law had spent more than $100,000 on commemorative gold coins. He did some digging around and found other instances of people giving large sums of money to U.S. Money Reserve, and he got in touch with a numismatist (an expert in coins). “Their value is about a third of what they paid for them,” Steckler says.

Steckler learned that the company had been ordered by the Texas attorney general’s office to pay up to half a million dollars in restitution to customers in 2011 for selling commemorative coins and claiming they would increase in value. Now the company sells gold and bullion, and it claims it no longer sells commemorative coins. The issue, for Steckler, is whether their customers fully understand what they’re getting themselves into. “They’re selling it as an investment or some sort of protected asset,” he says.

This is a point that Francine Breckenridge, U.S. Money Reserve’s chief compliance and legal officer, disagrees with. “It’s not an investment,” she told me flatly. “It’s not like a stock or something like that.” But the language used in most of the company’s sales pitches implies that the gold serves the same function. Breckenridge even told me that they recommend a 10-year hold to customers with every sale. You know, a bit like how you would treat an investment? The same video warning of terrorist threats also claims, “You can make money with gold. Gold is on the move, and you need to act now in case gold prices go from around $1,300 an ounce to $5,000 an ounce, as many experts are predicting.”

On the surface, U.S. Money Reserve sells gold, and they do essentially sell it for market rates. A particular coin might have a $5 currency denomination, but that number is irrelevant because the value of the gold itself makes it worth much more than that. For example, the current value of 1 ounce of gold as I write this is $1,195. At the same time, U.S. Money Reserve is selling a 1-ounce gold American Eagle Coin, produced by the U.S. Mint, for $1,267, which is not an unreasonable markup. Their prices adjust with the market price of gold.

It is after this initial sale, according to Steckler, when the questionable salesmanship occurs. U.S. Money Reserve will allegedly then call a customer back, trying to sell rare coins for more than their gold value. In 2015, Steckler represented Erica Stux in a class-action lawsuit against U.S. Money Reserve in California. The matter was settled under undisclosed terms. But the suit alleged that Stux was “solicited over the phone by the defendant 14 times in seven months, eventually purchasing over $250,000 worth of coins” under the assumption they were an investment. Upon appraisal, “the coins were found to be worth less than one-third of what Ms. Stux was asked to pay.”

“They’ll become friendly,” Steckler says, explaining the follow-up calls. “They’ll talk for hours. It’s like a car salesman. They’re good at it. These people are professionals at what they’re doing.”

An expert working for a consumer advocacy organization told me this is a common tactic in the industry. He claims that he once bought what he knew was a reasonable amount of gold for near market value. Then the calls came, pushing for more. When he rebuffed them, they responded with questions like “Don’t you want to protect your family?”

Since the class-action lawsuit against U.S. Money Reserve in California, clients have found Steckler. Or rather, their sons, daughters, nephews, nieces, and grandchildren have found him. Ultimately, elderly people who are clear of mind are free to spend their money however they wish. The U.S. Money Reserve’s Breckenridge read me a script that is recited with every sale informing customers that losses are possible and confirming that they are not associated with the U.S. government. The script also recommends that no one put more than 30 percent of his or her liquid net worth into precious metals. And assuming that it’s sold at near-market value, it’s certainly possible to make a profit from gold.

Videos like the one U.S. Money Reserve released last year work through fear tactics. They are hinting at a world where you’ll have to slip someone a gold coin to get to the other side of the Canadian border. And it is bolstered by the endorsement of Philip Diehl. “This is someone using his former position with the government who appears to be frightening people into purchasing these coins,” Steckler says.

Steckler considers U.S. Money Reserve to be predatory. When I brought up the possibility that the company targets elderly people, Breckenridge responded, “That’s just blatantly false.” They don’t cold call anyone who hasn’t already contacted them, she says, and they don’t ask the age of their customers.

Steckler, however, knows the age of his clients, and he says he just wants to get them their money back. He says that he was able to file a class-action lawsuit with his California client because the state has strict laws pertaining to the abuse or defrauding of the elderly. “Unfortunately, in the state of Texas, it’s really difficult to bring up class-action claims against companies,” Steckler says. For that reason, he takes on each client on a case-by-case basis, hoping to reach a resolution with the Austin-based company before resorting to litigation.

So perhaps your grandmother will see that video and reach for her phone out of fear the market is going to crash or North Korea is about to launch its nukes. Maybe she will call and make a small initial purchase, only to later put a large chunk of her retirement fund into gold coins. Or maybe it’s less dramatic than that. It’s possible she just isn’t too excited about stock in Google or Netflix, companies that didn’t even exist 25 years ago.

Why do that when gold, which has been around forever, is on the move?

Philip Diehl is telling your grandmother she needs to be prepared. When that attack comes, everything could change, and she’d better have some gold. Diehl, who was born in Dallas, was the 35th director of the U.S. Mint, a job he left in 2000. Now he is the president of something called U.S. Money Reserve. The former is one of the oldest agencies in the federal government. The latter, in tiny type at the bottom of its website, disclaims: “Not affiliated with the U.S. government and the U.S. Mint.”

The threat of a terrorist attack is part of a two-minute infomercial uploaded to YouTube in October 2017 that also features images of a man wearing a Middle Eastern headdress, his face hidden, holding an assault rifle above his head; a mushroom cloud from a nuclear explosion; and graphs depicting a stock market crash as the result of “cyberthieves, bank failures, and national debt.” It is all set in the context of a staged press conference, with Diehl standing at a podium, facing a gallery of fake reporters. Behind Diehl is a vault, guarded by fake cops. Off to the side, there are real American flags. One final detail: Diehl’s podium bears a seal, the bottom half of which is obscured by a caption displaying the phone number for U.S. Money Reserve and the message “America in crisis mode.” The top half of the seal, the only part visible, says “U.S. Mint Director.”

Perhaps it was this specific video that convinced an elderly member of a prominent Dallas family to pay six figures to U.S. Money Reserve for some gold coins. Bruce Steckler, a Dallas-based lawyer who represented that family, has met or represented people from here and elsewhere who have bought as much as half a million dollars in gold from the Austin-based company. According to Steckler, what they ended up with was not worth what they paid.

“This is someone using his former position with the government who appears to be frightening people into purchasing these coins,” says Bruce Steckler, a Dallas-based lawyer.

It all started for Steckler a few years ago when his wife’s college roommate called him out of the blue. Her elderly mother-in-law had spent more than $100,000 on commemorative gold coins. He did some digging around and found other instances of people giving large sums of money to U.S. Money Reserve, and he got in touch with a numismatist (an expert in coins). “Their value is about a third of what they paid for them,” Steckler says.

Steckler learned that the company had been ordered by the Texas attorney general’s office to pay up to half a million dollars in restitution to customers in 2011 for selling commemorative coins and claiming they would increase in value. Now the company sells gold and bullion, and it claims it no longer sells commemorative coins. The issue, for Steckler, is whether their customers fully understand what they’re getting themselves into. “They’re selling it as an investment or some sort of protected asset,” he says.

This is a point that Francine Breckenridge, U.S. Money Reserve’s chief compliance and legal officer, disagrees with. “It’s not an investment,” she told me flatly. “It’s not like a stock or something like that.” But the language used in most of the company’s sales pitches implies that the gold serves the same function. Breckenridge even told me that they recommend a 10-year hold to customers with every sale. You know, a bit like how you would treat an investment? The same video warning of terrorist threats also claims, “You can make money with gold. Gold is on the move, and you need to act now in case gold prices go from around $1,300 an ounce to $5,000 an ounce, as many experts are predicting.”

On the surface, U.S. Money Reserve sells gold, and they do essentially sell it for market rates. A particular coin might have a $5 currency denomination, but that number is irrelevant because the value of the gold itself makes it worth much more than that. For example, the current value of 1 ounce of gold as I write this is $1,195. At the same time, U.S. Money Reserve is selling a 1-ounce gold American Eagle Coin, produced by the U.S. Mint, for $1,267, which is not an unreasonable markup. Their prices adjust with the market price of gold.

It is after this initial sale, according to Steckler, when the questionable salesmanship occurs. U.S. Money Reserve will allegedly then call a customer back, trying to sell rare coins for more than their gold value. In 2015, Steckler represented Erica Stux in a class-action lawsuit against U.S. Money Reserve in California. The matter was settled under undisclosed terms. But the suit alleged that Stux was “solicited over the phone by the defendant 14 times in seven months, eventually purchasing over $250,000 worth of coins” under the assumption they were an investment. Upon appraisal, “the coins were found to be worth less than one-third of what Ms. Stux was asked to pay.”

“They’ll become friendly,” Steckler says, explaining the follow-up calls. “They’ll talk for hours. It’s like a car salesman. They’re good at it. These people are professionals at what they’re doing.”

An expert working for a consumer advocacy organization told me this is a common tactic in the industry. He claims that he once bought what he knew was a reasonable amount of gold for near market value. Then the calls came, pushing for more. When he rebuffed them, they responded with questions like “Don’t you want to protect your family?”

Since the class-action lawsuit against U.S. Money Reserve in California, clients have found Steckler. Or rather, their sons, daughters, nephews, nieces, and grandchildren have found him. Ultimately, elderly people who are clear of mind are free to spend their money however they wish. The U.S. Money Reserve’s Breckenridge read me a script that is recited with every sale informing customers that losses are possible and confirming that they are not associated with the U.S. government. The script also recommends that no one put more than 30 percent of his or her liquid net worth into precious metals. And assuming that it’s sold at near-market value, it’s certainly possible to make a profit from gold.

Videos like the one U.S. Money Reserve released last year work through fear tactics. They are hinting at a world where you’ll have to slip someone a gold coin to get to the other side of the Canadian border. And it is bolstered by the endorsement of Philip Diehl. “This is someone using his former position with the government who appears to be frightening people into purchasing these coins,” Steckler says.

Steckler considers U.S. Money Reserve to be predatory. When I brought up the possibility that the company targets elderly people, Breckenridge responded, “That’s just blatantly false.” They don’t cold call anyone who hasn’t already contacted them, she says, and they don’t ask the age of their customers.

Steckler, however, knows the age of his clients, and he says he just wants to get them their money back. He says that he was able to file a class-action lawsuit with his California client because the state has strict laws pertaining to the abuse or defrauding of the elderly. “Unfortunately, in the state of Texas, it’s really difficult to bring up class-action claims against companies,” Steckler says. For that reason, he takes on each client on a case-by-case basis, hoping to reach a resolution with the Austin-based company before resorting to litigation.

So perhaps your grandmother will see that video and reach for her phone out of fear the market is going to crash or North Korea is about to launch its nukes. Maybe she will call and make a small initial purchase, only to later put a large chunk of her retirement fund into gold coins. Or maybe it’s less dramatic than that. It’s possible she just isn’t too excited about stock in Google or Netflix, companies that didn’t even exist 25 years ago.

Why do that when gold, which has been around forever, is on the move?

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Dallas’ most important news stories of the week, delivered to your inbox each Sunday.