Not long ago, I received a phone call with the greeting: “Hey, buddy, it’s your old cellmate.”

Not long ago, I received a phone call with the greeting: “Hey, buddy, it’s your old cellmate.”I told him, “I’m afraid you’ve got to be more specific.”

It was my old friend J. Carl Fite. Back in the day, nearly 50 years ago, he was the handsome, mustachioed six-year veteran Dallas Police Department detective and former rookie of the year who got himself fired, in part, for helping me and other reporters reveal wide-ranging illegal activities on the part of the police department’s vice and narcotics squads.

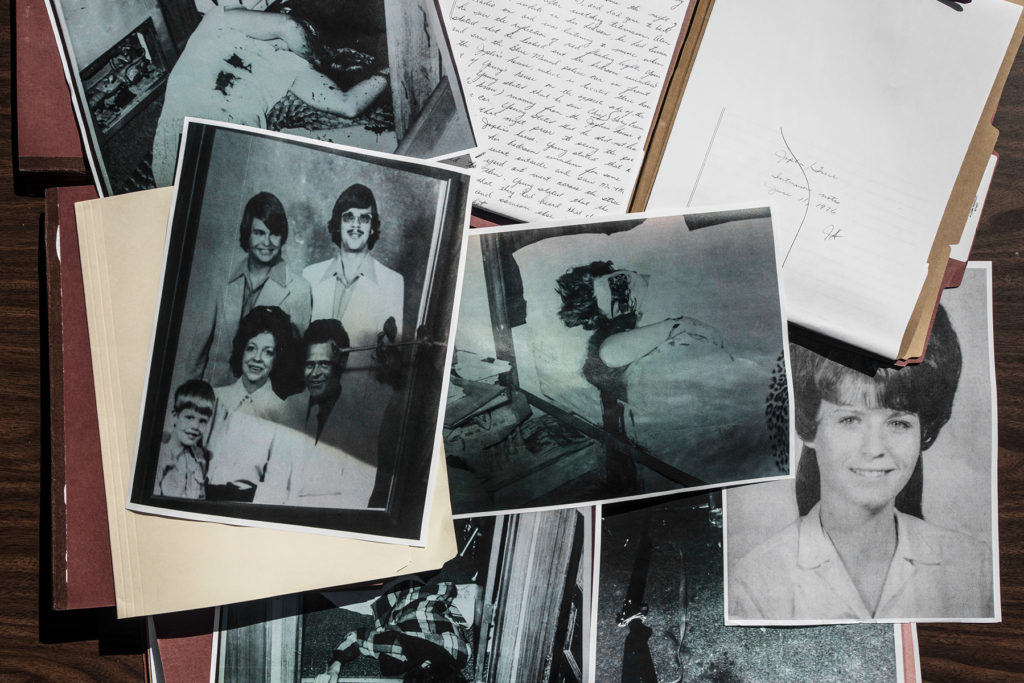

Carl and I were arrested and jailed together 42 years ago while investigating a mass murder in Blue Mound, a tiny blue-collar town just north of Fort Worth, where interstate highways 35W and 820 intersect. It was a ghastly crime, an execution-style, close-quarters shooting of four family members—all in their nightclothes. Sometime around 11 pm on the night of February 23, 1976, Wayne Joplin, 42, his wife, Faye, 41, sons Brian, 17, and Kevin, 6, were all shot in the head. A neighbor named Terry Trice, 17, was also found dead in the home.

Gregg Joplin, 20, was the oldest of the three boys and only family survivor. He wore large glasses that looked like safety goggles reaching up to his forehead, almost touching the bangs of his bowl haircut. He worked for a Fort Worth surveying firm, and several acquaintances independently called him a genius. He told police that he’d been at his aunt’s house the night of the murders. After driving around for 30 to 45 minutes, he said, he returned home. He talked to the media just once about what happened that night. Here’s how he was quoted by the Associated Press:

“I went home and turned my key in the door. When I opened the door, I saw my mother by the door. I just knew she was hurt bad. …

“I heard someone moving around. It seems like I said, ‘Who is it?’ or something like that.

“I’d been target shooting a few days before, and I hadn’t cleaned my .22 yet. It was right behind the front door. I had my field jacket hanging there, and it had some ammunition in it. I put a round in it, and I saw someone cross my line of vision, and he had a rifle, too. I stepped toward him a couple of steps and said, ‘Freeze!’ When he didn’t, I shot him.” It was dark in the house. “I aimed at a shape,” Gregg said. “I guess you could call it a lucky shot. …

“I walked to an end table and turned on a light. I went to a phone by the light, and I saw my dad there. There was blood all over the hall. I called the police, and then I ran outside.”

What happened next put a shroud over the entire investigation that lasts to this day. Blue Mound Police Chief Gary Erwin, who was 29 and had never faced such a crime, arrived to find the gruesome scene. Wayne and his middle son, Brian, had defensive wounds. The father, a supervisor at a canning factory, had part of his hand and face blown off. Kevin, the 6-year-old, was found lying in a pool of blood, wearing his Mickey Mouse pajamas.

An autopsy of the neighbor, Trice, showed that his death resulted from a single .22 caliber bullet entering from behind his ear. According to Chief Erwin, Trice was found on the floor, near a back doorway, with a British model .303 Enfield rifle by his side and an antique black powder cap-and-ball pistol tucked under his belt. But it’s unclear, really, what Erwin found because he mucked up the investigation by handling evidence himself and allowing others—even curious neighbors—to contaminate the crime scene by picking up guns and spent hulls and even digging bone fragments out of the sheetrock. Erwin said he picked up the Enfield rifle and the pistol from under Trice’s belt because he thought Trice might still be alive. Of the two guns, Tarrant County Sheriff Lon Evans said everybody “this side of Altus [Oklahoma] handled them.” When they were turned in as evidence, there were no viable fingerprints on the weapons, almost as if they had been wiped clean.

When Gregg was told about the rifle found beside Trice’s corpse, he told the AP, “The .303? God, was that what he used? That was my gun! He even used my own gun!”

Still, despite the incompetence of Erwin, there remained, perhaps, enough physical evidence to give investigators a starting point to confirm or refute Gregg’s account of what had transpired. But officers arriving at the scene failed to order that Trice’s hands be wrapped so that a basic trace metal detection test could be run to see if he might have fired a weapon that night. Other tests to determine if he had fired a weapon were also ignored. The Tarrant County Medical Examiner’s office told me at the time that they were responsible only for determining the cause of death and not for “ordering out-of-the-ordinary tests.” A spokesman for the same office in Dallas County told me at the time that such tests are conducted in murder investigations “as a matter of course and curiosity.”

Investigators did ask the medical examiner to check Trice’s shoes and clothes for blood. Except for a small bloodstain on the sole of Trice’s left shoe that was “insufficient for further characterization,” a bloodstain on the leg of his pants was believed to be type B. Why that is so important: Trice was type B. Wayne and his middle son were type O. Faye and her young boy were type A. You might think an assailant roaming room to room, executing victims at short range, and scuffling with two of his victims would end up with some blood on his person—at least on his shoes.

From the get-go, the authorities who botched the case tried to cover their asses. Both a Tarrant County sheriff’s investigator and the medical examiner were quoted in the media as being certain that Trice was there to burglarize the house. For what? Gregg himself said there were no valuables in the house. Trice had no car or bag to transport stolen goods. Would a couple of guns be enough booty to lead to the killing of four people? Could a 150-pound 17-year-old with little knowledge of firearms outmuscle a grown man and another teenager in all the mayhem and not have their blood on his clothes?

At this time, in 1976, D Magazine was less than two years old and not really sure where it was going. The same could be said for the writers, including me, and Wick Allison, the guy who started the magazine and owns it to this day. The shooting death of five people in a small community 40 miles west of Dallas didn’t seem a likely candidate for coverage. But quickly enough the discrepancies popped up, warranting real interest. So off I went.

At this time, in 1976, D Magazine was less than two years old and not really sure where it was going. The same could be said for the writers, including me, and Wick Allison, the guy who started the magazine and owns it to this day. The shooting death of five people in a small community 40 miles west of Dallas didn’t seem a likely candidate for coverage. But quickly enough the discrepancies popped up, warranting real interest. So off I went.The Blue Mound population then and now totals about 2,300 and is made up primarily of skilled and unskilled laborers. “There isn’t a less intelligent collection of human souls on God’s green earth,” one law-enforcement official told me repeatedly in my early explorations. I went nearly door to door looking for background information on both Gregg Joplin and Terry Trice. The results were maddening, as I encountered wild rumors, impossible accusations, and maudlin suspicions at every turn.

There were stories of young witnesses seeing something that looked like a body being dragged into the Joplin home on the night of the murders. Rumors abounded that both Gregg and his father, Wayne, were sleeping with Gregg’s aunt.

On the believable side, there was the consistent notion that Gregg was a quiet but stable loner. In terms of family unrest, Gregg told a grand jury that he was upset with his mother over her spending habits, saying he believed she had been extravagant with not only the family income but also a recent $3,975 bequeathal from her sister’s estate (about $18,000 today, accounting for inflation).

Trice, on the other hand, was going through a period of melancholy. Not only had his father committed suicide, but his older sister had died of a drug overdose just prior to the murders. He’d dropped out of school lacking only two credits to graduate, quit going to church, and mostly stayed home looking after his mother, who had taken to drinking heavily.

One witness, Marie Gomez, told others and me that she had seen Gregg and Trice together in a vehicle the night of the murders. But that’s not what she told police. More about her later.

Put simply, the town and its residents were a mess. Chief Erwin would resign just three months after the murders. One law-enforcement officer involved in the case told the AP, “I don’t blame him for quitting. Everyone we ran into out there was nuts.” But one fact soon became clear to me: Tarrant County sheriff’s deputies and the Blue Mound police chief were displeased with my reporting efforts.

I was stopped with my friend Carl, the former cop, who was helping me with interviews, and arrested for a handful of felonies. I remember that “interfering with a murder investigation” was one and “attempted murder with a motor vehicle” was another. But my favorite was “enticing a child.”

I was at the Trice home and was told that Gregg was staying at a nearby motel. I asked Trice’s teenage girlfriend if she could identify Gregg’s car. She said yes, and Carl and I drove to the motel parking lot. Gregg’s car wasn’t there, so we took her back to the Trice home. That was it.

Three sheriff’s deputies and Chief Erwin were curious why some guy from Dallas was in Blue Mound interviewing witnesses and friends of the deceased. I said that if they had done their jobs right to begin with, I would not have been there. That’s when Carl and I got arrested. We were hauled off to the Saginaw jail. One of the deputies slapped Carl’s testicles before putting him in a cell separate from mine. No phone calls were allowed to either a lawyer or the magazine. (After going through the ordeal, it came as no surprise to me when one of the main investigators was later sent to prison on bribery charges.)

By chance, though, we had a friend along that day who did not get arrested. He made it back to Dallas and informed Wick of our dilemma. He arranged for a magazine attorney to call Chief Erwin, who answered and then hung up. By that point we had spent about eight hours in jail. The authorities had rummaged through my briefcase and were playing my interview tapes. They also broke into Carl’s car and illegally searched it.

Meanwhile, back in Dallas, another attorney was frantically trying to find a way to win our release. Finally a judge agreed to sign a writ but only if the attorney would bring him a carton of cigarettes. After 11 hours, we were released.

Soon I was on my way to Fort Worth, accompanied by noted media attorney Stephen Philbin, with a view to file suits for false arrests and false imprisonment. We found that the district attorney refused to accept Chief Erwin’s complaints, and no formal charges were ever filed.

The Tarrant County sheriff at the time was Lon Evans. He called in the deputies who had made the arrests, including the one who soon went to prison on bribery charges. They all apologized. When they left, the sheriff and I chatted about football and other matters. He was a member of the Green Bay Packers Hall of Fame. My college head coach had gone on to coach the Packers for three years, and Evans wanted to know more about him.

Then the conversation turned to Terry Trice and guns. Trice’s mother had told me that her son was not familiar with guns and hated them ever since his father had used one to kill himself. The weapon used in the slaying of the Joplins was an old .303 Enfield rifle that can be difficult to load, especially for a neophyte, because loading involves staggering as many as five bullets at a time to avoid an issue called “rim lock,” which makes the gun inoperable.

An assistant DA in the county, Charles Roach, said, “For someone unfamiliar with guns to load it four times and kill three adults—to hit four people in the head—I just don’t believe it.” Sheriff Evans concurred, saying to the press that Trice was “too awkward and unfamiliar with guns to be the killer.”

There is no way that being incarcerated can ever be a good thing. As a result of my ordeal, however, I won access to information and evidence not normally available to reporters. As I left his office, Sheriff Evans blurted, “Stephenson, I believe you could set the courthouse on fire and not be arrested now.”

Like many others, I was convinced Gregg Joplin was not telling the truth about his actions on the night of the murders. Still there was nothing solid that could rebut Gregg’s statement of facts, and, after all, he stated publicly and again before a grand jury that he would make himself available for polygraph testing. Then he changed his mind.

By now, some six weeks after the murders, I had pretty easily uncovered facts that investigators had inexplicably failed to unearth. For instance, Trice was wearing someone else’s coat when he was found shot to death, and, though he wore a size 11 shoe, he was found wearing size 9 sneakers.

More scrutiny produced more incongruity. Gregg said that after having shot Trice, he called the police. A dispatcher later recalled Gregg’s words: “My whole family is dead … shot to death.” He then hung up and ran out of the house.

By his own account, Gregg did not go to the back bedrooms to check on his younger brothers, Brian and Kevin. That’s where they were found. Gregg did not check to see if the intruder he’d shot was still alive and possibly a threat. He testified that he just ran. So how did he know his whole family was dead?

Then there was that lucky shot. His .22 was right there by the door. The ammunition was handy. Gregg told a grand jury that he never even shouldered the gun. It was a snap shot in the dark, right behind the ear. Perfect.

Gregg had to be subpoenaed to appear before that grand jury. The assembled jurors had serious questions about his version of events. The proceedings are secret, but I can report this exchange:

Juror: “Why didn’t you run back to the bedroom to see if [your brothers] were all right?”

Gregg Joplin: “All I wanted to do was call the police and get out of that house.”

Juror: “You were so emotionally upset that you felt like vomiting but you could instantaneously recall the telephone number of the police department, is that your testimony?”

Gregg Joplin: “Yes, sir. It’s not something you forget. I don’t forget many phone numbers at all but I made sure I memorized that one a long time ago.

“See, my mother attempted to commit suicide several months back and at that point I had to call the police, too, and I had to be cool and tell them what happened. At the same time, my dad had had a partial heart attack and fallen down on the floor. I had to be cool because there was no one else to do it.”

Juror: “What made you think that your mother hadn’t committed suicide that night?”

Gregg Joplin: “There wasn’t time to consider.”

Juror: “Did it ever enter your mind that she may have taken an overdose of sleeping pills and passed out on the floor?”

Gregg Joplin: “No, sir. There wasn’t time. …”

Juror: “And after you talked to the police on the telephone you didn’t go back in the bedrooms to see if anyone else was back there?”

Gregg Joplin: “No, sir. I didn’t.”

Juror: “Why didn’t you do that?”

Gregg Joplin: “Because I wanted out.”

The grand jury got little help. The jurors were denied a visit to the murder scene when members had voted 11−1 to do so. They were denied access to medical examiner and autopsy reports that even I already possessed while working on the story for D Magazine. One of the more able assistant district attorneys admitted, “We weren’t there to get an indictment.”

So, it appeared, any real shot at determining what really happened that night had ended. As months ticked by, Chief Erwin left his job, Gregg moved away and married. Unknown to authorities until months after the murders, Gregg was the beneficiary of more than $32,000 in life insurance and other monies, plus proceeds from the sale of the house and family vehicles. (With inflation, the insurance policy was worth more than $130,000 in today’s dollars.)

And then, just a few months later, the gruesome Blue Mound massacre was pushed aside by another sensational Tarrant County murder, this one committed at a $6 million mansion on a prize bluff in Fort Worth. The suspect was Cullen Davis. At that time, Davis was the richest man ever accused of capital murder. Four people were shot. Two were dead. Davis’ wife, the alluring Priscilla Davis, was seriously wounded.

Like so many young Labradors, the media pack chased this tennis ball that promised murder, money, sex, drugs, and chicken-fried steak. I pursued it as hard as anyone, thinking I had my first book in sight and, for a long time, did not think much about the Joplin murders. Occasionally I would make inquiries about Gregg Joplin, thinking his name might pop up in connection with another violent episode somewhere. I thought about what District Attorney Charles Roach had told the Associated Press: “It will always be my opinion that somebody knows something about this case. They haven’t leveled with us or haven’t come forward.”

Sheriff Evans, who never quit looking for the murderer, said, “I believe the killer will slip up somewhere, sometime.”

Maybe. Just maybe he has.

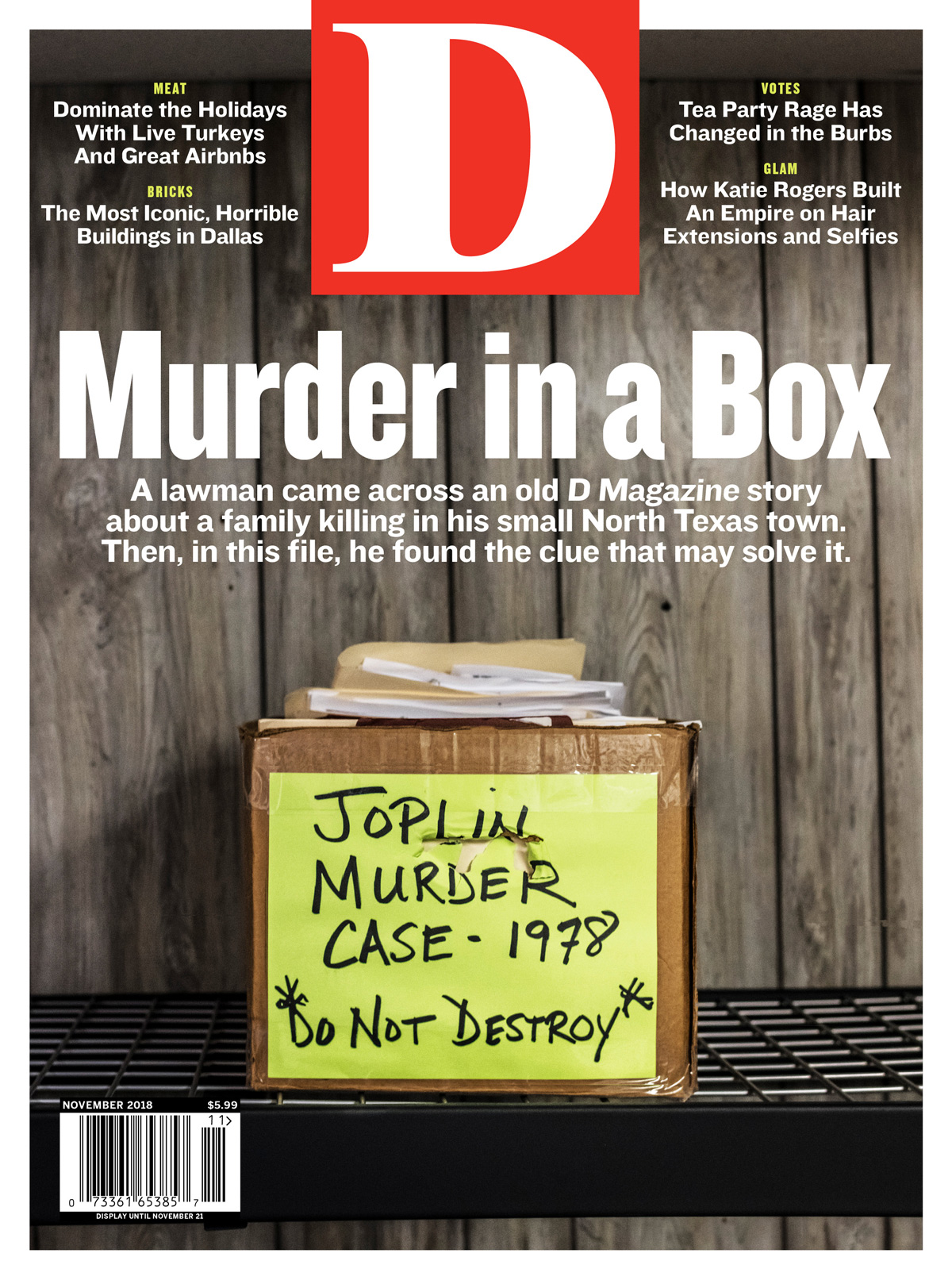

That recent phone call from my friend Carl jarred my old memories enough to google Gregg Joplin’s name to see if he had made any new headlines. That is when I saw the jaw-dropping headline in the Star-Telegram: “Person of Interest Emerges in Unsolved 1976 Blue Mound Murders.” The article was written in October 2015, but, like so much with this case, there was no follow-up. So I followed up.

That recent phone call from my friend Carl jarred my old memories enough to google Gregg Joplin’s name to see if he had made any new headlines. That is when I saw the jaw-dropping headline in the Star-Telegram: “Person of Interest Emerges in Unsolved 1976 Blue Mound Murders.” The article was written in October 2015, but, like so much with this case, there was no follow-up. So I followed up.The article mentioned how another Blue Mound police chief, Barry Hinkle, had years ago begun looking into the nearly 40-year-old murder file and come upon an old jailhouse letter that fingered a suspect who had, apparently, never been questioned.

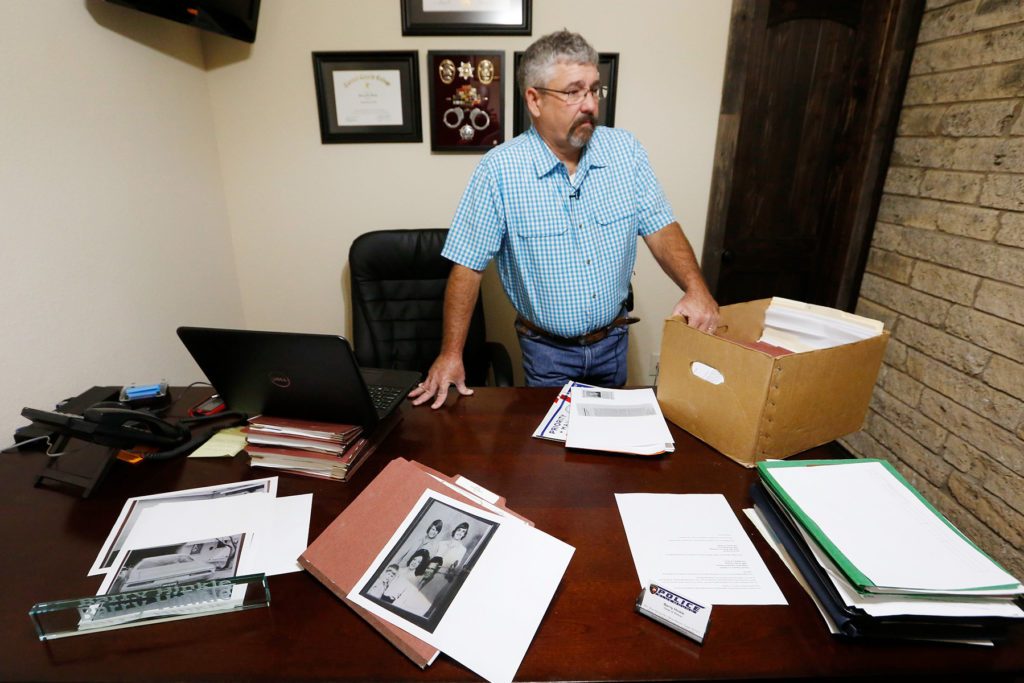

Finding Hinkle was not easy. He had had a spat with the City Council—dead animals were found in the city’s water supply, and he’d filed a complaint with state environmental regulators—and Hinkle was fired in 2016, leading him to file a whistleblower lawsuit in return. I found his lawyer, who relayed my number to the sharp and inquisitive former chief.

Hinkle came to Blue Mound after 22 years as an officer at the Southlake Police Department, where he retired as a lieutenant in the criminal investigations division. While still in Keller High School, Hinkle had been a volunteer for the Colleyville Fire Department before deciding to become a cop. He now has a master’s degree from SMU in human development. At 55, he wears a neatly trimmed goatee and mustache and fashionable spectacles, and his mostly dark hair is graying. He was first hired to do some auditing for Blue Mound. With his organizing and attention to detail, he excelled at the job. He reorganized the property evidence room and proposed other policy adjustments that created wholesale changes in both the department and the city government. Eventually he won the job of police chief.

There are people who will tell you that Hinkle is a bit of a conspiracy theorist. He may well be. But he has an appetite for detail and a physical energy that fuels exhausting research. The first document he sent me was a single-spaced, 48-page, just-the-facts-ma’am narrative outlining his yearslong investigation. It began: “On or about August 9, 2011, Deputy Chief Barry Hinkle was conducting general internet research on the behalf of the City of Blue Mound. During the research, Hinkle discovered a 1976 D Magazine article titled ‘The Bungling of the Blue Mound Murder Case,’ by Tom Stephenson.”

After reading my story, Hinkle went looking for documents, only to find that there was not even a report on file at the Blue Mound PD. He asked the Tarrant County Sheriff’s Office to help. So began more than seven years of official and unofficial investigating. “What really drove me,” he told me, “was to see the lack of justice for a 6-year-old boy shot between the eyes. That is not right. Just not right.”

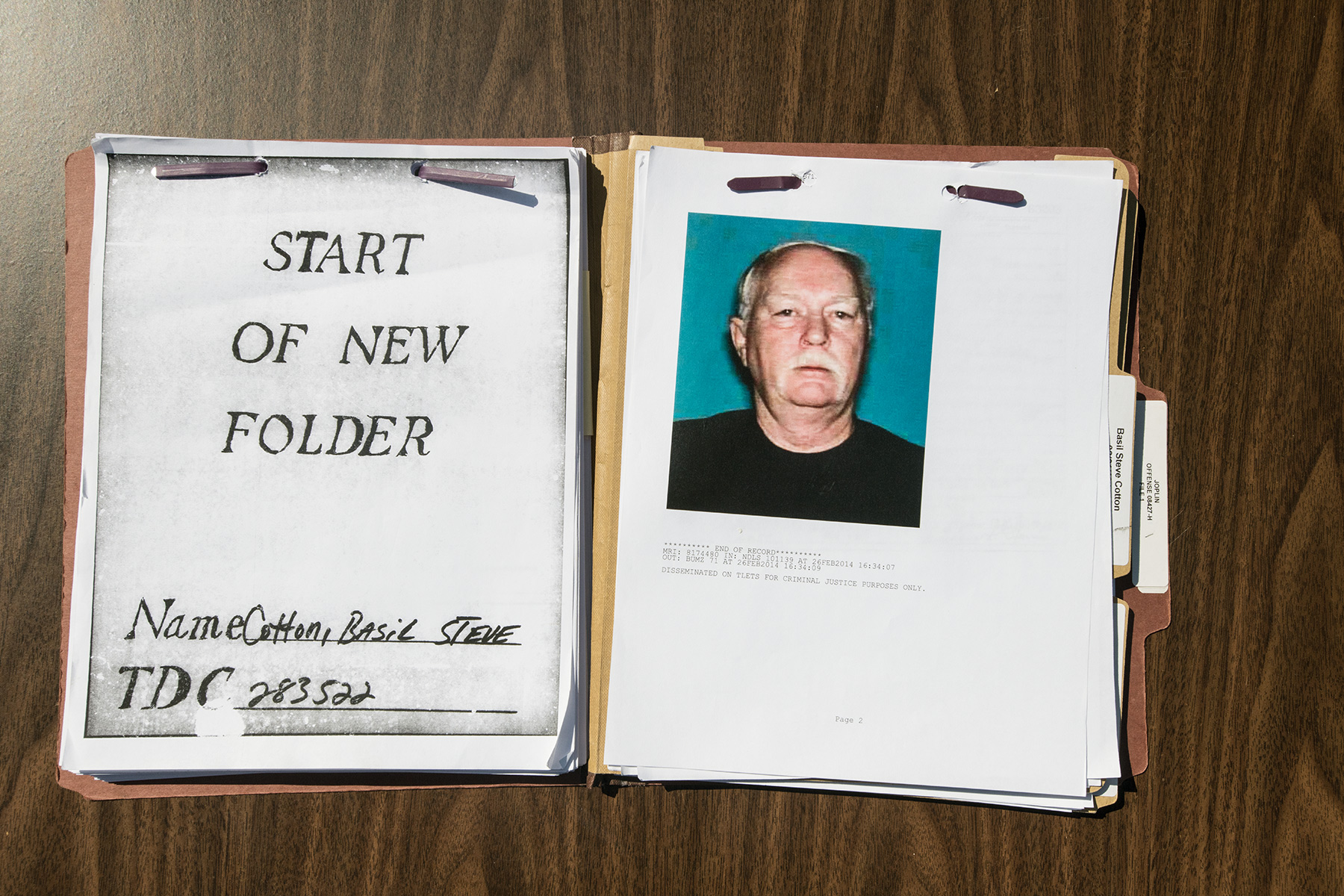

Eventually Hinkle got his hands on an old box filled with information on the case. And buried in those thousands of pages was a jailhouse letter written by a 27-year-old man named David Newberry to his wife. Writing two years after the Blue Mound murders, Newberry took his wife to task for having smoked weed with a man named Cotton, who was in jail with Newberry. Cotton not only told Newberry that he’d gotten high with Newberry’s wife, but he also apparently confessed that he’d killed his own ex-wife, a woman who Newberry’s wife knew. It’s all a bit convoluted, as jailhouse letters tend to be, but in that old box, Hinkle also found a sworn statement signed and written in Newberry’s hand. It read:

“My full name is David Arnold Newberry. I am a white male 27 years old. I was born 8-27-51. I finished the 6th grade in school and can read and write the English Language but not very good. I am presently in TDC at Huntsville, TX.

“On 12-4-78, I was in the Tarrant County Jail at Fort Worth, TX, in H tank on the 7th floor. Also a white male named Cotton who is about 35, short, heavy build and partially bald with gray hair was in the same tank.

“We had been in this tank together for about a week. On 12-4-78 we were in Cotton’s cell when Cotton begin bragging about killing people. He told me that he had killed his wife named Portia because he was jealous of her and a guy named Mike who has a funny name like Brasseare.

“Cotton said he had killed a man named Bill Hatfield but didn’t say why he had done it. Then I asked Cotton what does he get out of killing people, and he said, ‘That ain’t nothing. I could tell you something else.’ I asked him what he was talking about, and he said he could tell me about a family he had killed. I said, ‘Well, tell me then.’ And he said he had never told anyone but it had happened about 2 years ago. I said, ‘Man tell me. I ain’t going to say nothing.’ Cotton asked me if I had ever had the urge to tell someone about something you had done and I said ‘yes.’ Cotton then said the family’s name was Joplin and it happened in Blue Mound, TX. I told him to go ahead and tell me the rest of it.

“I did not know about any family being killed at Blue Mound at the time Cotton was telling this to me. Cotton said that he had met about 3 times with one of the family and this family member was a male, but Cotton didn’t call his name.

“Anyhow the Joplin man wanted Cotton to kill the rest of the family so the Joplin man could get the insurance money and that he would pay Cotton for the killing out of the insurance money. Cotton didn’t say how much money he was to get for the killing. Cotton said the Joplin man was going to set up one of his friends to be blamed for the murder of the Joplin family.

“Cotton said he went to the Joplin House and went in and shot the family. He said the Joplin man was waiting around the corner at a grocery store. … Cotton said the Joplin man came in the house and had another young man with him. After the Joplin man and the other man got in the house, the Joplin man shot the young man who had come in with him and at this time Cotton left.

“Cotton said that the Joplin man was going to call the police and tell them he had come home and found the other young man there and had shot him and that he (Joplin man) would call Cotton the next evening and he did call. He told Cotton he would have the money in about a month or so.

“Cotton said that the Joplin man had only given him part of the money and he got mad and told the Joplin man that he was going to the police. The Joplin man told him to go right ahead because Cotton would get in trouble.

“About the time Cotton told me this much, the jailers made us go to our own cells and I didn’t get to talk to him (Cotton) anymore.”

The statement was signed by a Tarrant County deputy sheriff. Of course, jailhouse testimonials are often considered puny evidence, but Hinkle and others say they could not see any direct benefit to Newberry for telling his story. There were no records in the old file deciphering who exactly this Cotton character was, and no one apparently bothered to investigate back in 1978 what Newberry had told authorities. It wasn’t until Hinkle came along in 2011, read my old D Magazine story, and started poking around that Cotton’s identity emerged. Hinkle worked for months before finally discovering a marriage certificate that connected a Portia Brussow to a man named Basil Steve Cotton. That is the woman whose murder Cotton had been charged with before he skipped bail, got captured, and was sent to the Tarrant County jail, where Newberry said he met him. Hinkle would learn that Cotton amassed more than 20 arrests for, among other crimes, injury to a child, simple battery, aggravated battery, a half-dozen or so DWIs, and manslaughter (twice). Gregg Joplin, by the way, died in Humble, Texas, from heart failure in 2005, closing the door on any enlightenment from him.

But Hinkle was convinced Newberry was telling the truth in his jailhouse statement. “He had details no one else would have unless he was actually there or explicitly told about it, like the part about the grocery store near the Joplin house,” Hinkle told me. “No way he lied if he is giving those great incidental details.”

Somehow, over the course of his investigation, Hinkle and detective Clifton Kirby managed to get both Newberry and Cotton to sit for interviews. Both played the “I know nothing” game as expected, but Hinkle says Newberry, who died shortly after the interview, “never once recanted his statements about the Joplin murders and Cotton.”

Hinkle remains convinced that the Joplin murders aside, Cotton has killed multiple people in his lifetime. But in his interview with Hinkle, Cotton downplayed any stories he may have told to another inmate. A transcript:

Basil Cotton: “When you’re in jail with a bunch of goddamn men.”

Barry Hinkle: “Yeah.”

Basil Cotton: “You say shit to make yourself look meaner so people don’t jump on you and try to rob you or screw you in the butt or something.”

Barry Hinkle: “Well.”

Basil Cotton: “But I hadn’t killed anybody. I’m not worried about that because I know I didn’t do it, and, if I didn’t do it, I don’t think anybody can prove anything because I’m as innocent as a lamb about that. I haven’t done anything so …”

With Gregg Joplin dead, David Newberry dead, and scores of others passing on, where does that leave us? Well, there is Marie Gomez, who told me 42 years ago and later passed a polygraph saying that she saw Terry Trice get in a car with Joplin the night of the murders. She said that from her window she saw a light-colored vehicle on the wrong side of the street and could see Trice get in the vehicle. When the interior light came on, she said, she recognized Gregg as the driver, and the vehicle departed without headlights.

With Gregg Joplin dead, David Newberry dead, and scores of others passing on, where does that leave us? Well, there is Marie Gomez, who told me 42 years ago and later passed a polygraph saying that she saw Terry Trice get in a car with Joplin the night of the murders. She said that from her window she saw a light-colored vehicle on the wrong side of the street and could see Trice get in the vehicle. When the interior light came on, she said, she recognized Gregg as the driver, and the vehicle departed without headlights.So that leaves us with Basil Cotton. I learned that he is still living and is 74 years old. I found his address and went to his trailer in Alvarado, a small town south of Fort Worth, where he has lived for many years. But like so much of this case, that chase led to nothing. When I got there, his trailer and all belongings had been recently moved. I could see the tire tracks where his trailer had been pulled from the lot.

Next I found a relative who had been listed on Cotton’s old prisoner visitation list. She had a new phone number for him but not an address. She also told me Cotton “was on oxygen 24/7.” Posing as a utility worker, I called the number to ask if there was any reason we should not cut off power to the house while we did repairs. A woman who answered the phone told me about the situation with the oxygen and gave me the address.

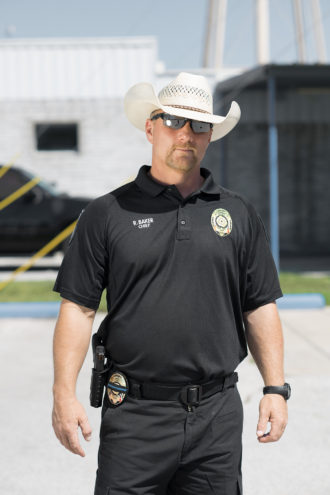

Fortunately, the new police chief in Blue Mound, Randy Baker, had also taken an interest in this cold case and was helping get copies of certain files I needed to pin down facts. Baker is a short, powerfully built man who earned a college scholarship as a rodeo bronc rider. He appears to be afraid of absolutely nothing, which I saw as a very good trait when he offered to go along with me to meet Basil Cotton.

On the drive from Blue Mound to the trailer in Alvarado, in late September, we talked about the dim prospects of Cotton admitting any involvement in the Joplin murders. “I’m not sure he will even let us in the house,” Baker said.

We pulled up in Baker’s squad car and parked just out of view. Baker checked his M&P Shield 9 mm, and we walked the short distance to Cotton’s trailer home. It was in disrepair and showed no signs of anyone living there, save for the running AC unit in an adjoining travel trailer.

We climbed the steps, and Chief Baker knocked on the door before ducking back so as not to be seen through the windows. A woman answered after the second knock, and we tried to enter together, but there were two dogs that would have none of it—especially the pit bull mix with a head the size of a huge pumpkin.

I don’t know what I expected to see or feel at this meeting. I knew Cotton had suffered a stroke and had back surgery in recent years. Though still somewhat stout for a man his age, he appeared meek, almost pitiful.

With the friendly dog now outside, Cotton sat on a couch and, while breathing oxygen through a tube connected to a machine, stroked the massive head of the pit bull that sat at his feet. He wore shorts and a black t-shirt with the sleeves cut off.

There were no introductions. I started out by telling him that I had been working on a cold case for a few years and that I wanted his help in solving it. My first question was: “Did you know or have you ever been asked about a person named Gregg Joplin?”

He responded in the negative, and then I mentioned a murder in Blue Mound. Just that mention set him off a bit.

“Yeah,” he responded. “That Blue Mound cop asked me about that. So, yeah. And I remember after that, a bunch of shit came out in the newspapers about a suspect. So I ain’t talking about that.”

I mentioned that almost an entire family was killed, and he responded, “Yeah, a family was killed down from where my ex-mother-in-law lived.”

“Did she live at 1604 Glenn?” I asked. The Joplin murders took place at 1717 Glenn.

“I think so,” Cotton said.

“What did you tell that Blue Mound cop when he asked about the murders?”

“I don’t know, but I am pretty sure I was in Atlanta, Georgia, then. I lived in Atlanta, Georgia, for six or seven years when all this happened.”

“When did you say you were in Atlanta?”

“From about 1971 until the mid-’70s.”

“Are you sure you were not in Blue Mound?”

“I dunno,” Cotton said. “I stayed drunk five years—or 10 years after Portia died.”

I asked Cotton how she died, knowing that he had killed her with one shot to the chest. That was probably a mistake on my part, as his demeanor changed and a rage seemed to boil up.

He told us to get out. Chief Baker is required to follow such instructions, and he started out the door. I tried to turn the conversation back to Blue Mound but it was too late. Cotton started yelling, and I noticed that he was no longer petting the dog. Instead he had the animal gripped tightly by the back of the collar.

His last words to me: “You get the fuck out of my house and don’t come back unless you have a goddamn warrant.”

We all knew when we started this process that it would not likely produce a made-for-TV confession in the end. But as Chief Baker backed his squad car off the property, he turned to me and said, “You know we just left the house of a stone-cold killer, don’t ya?”