This piece is a feature from our special edition, Dallas and The New Urbanism. The magazine examines the successes and pitfalls of the urbanist movement in a region well known for its dependence on the automobile.

This piece is a feature from our special edition, Dallas and The New Urbanism. The magazine examines the successes and pitfalls of the urbanist movement in a region well known for its dependence on the automobile.As the neighborhoods in and around downtown Dallas redeveloped in recent decades, they became hotbeds for millennials who, more than their parents did, rely on everything from walking and shared bikes to light-rail trains and ride-hailing apps to move around dense neighborhoods. But that still is not enough for the Dallas-Fort Worth area as a whole to fare well against other American metros in luring educated, young professionals to what continues to be an ever-sprawling region where car ownership is almost a necessity. This presents quite a conundrum for Kevin Feldt, who spends his workdays inside a nondescript Arlington office building trying to figure out how to build a future transportation grid for a new generation when political and financial inertia still heavily favor the kind of highway building that exacerbates the sprawl.

“Where are we headed?” Feldt asks. “And what does the future hold? That’s my dilemma.”

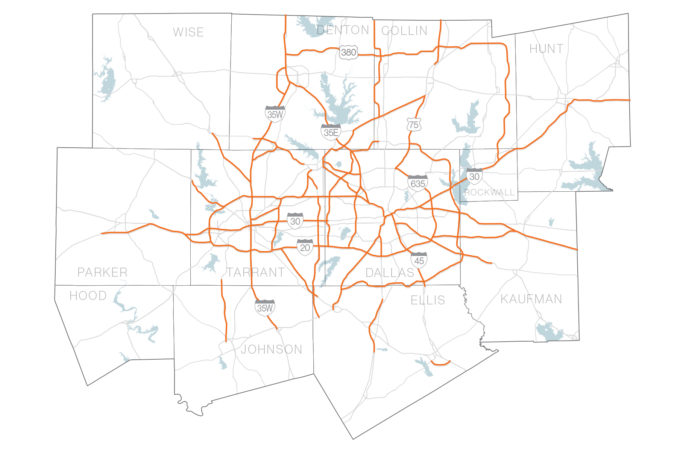

Feldt is a program manager for the North Central Texas Council of Governments, a government entity whose work includes planning how people will get from point A to point B decades from now. The agency’s plans influence a web of federal, state, and local entities as they spend billions of taxpayer dollars turning those plans into miles of new freeways, city streets, transit lines, and bike lanes. And even though millennials may be pushing away old ideas about what transportation infrastructure—and the development patterns it creates—should look like, NCTCOG’s proposed $135 billion plan for the future looks decidedly old school:

More than 58.1 percent of the $89.4 billion earmarked for capital projects is for road work, which includes everything from highways and tolled lanes to city streets.

About 15 percent of the $38.2 billion for major highway construction is budgeted for building freeways and corridor extensions that don’t yet exist, including $2.8 billion for a new regional loop north of Denton and McKinney.

Less than 3 percent of the $42.9 billion in traditional federal and state transportation revenues in the plan goes toward projects built for pedestrians and bicyclists; less than 1 percent goes toward public transit.

Almost two-thirds of the $33.3 billion earmarked for transit construction and service improvements is funded from revenue streams that do not exist yet.

One of the goals of the long-term plan, dubbed Mobility 2045, is to give people alternatives to driving everywhere solo. But that objective is undermined by the financing proposals that underpin it—and the political reality that highway projects are much easier to sell in the suburbs than pedestrian, bicycle, and transit projects.

“It’s a vicious cycle that’s going on here,” says Dallas City Councilman Scott Griggs. “It’s transportation planning right out of the 1950s.”

North Texas officials from various levels of government point to a number of reasons why transportation planning and financing still favor the highway over all other modes of mobility. The 2045 plan even envisions funding TxDOT’s vision for expanding Interstate 30 east of downtown. The agency’s draft engineering plan expands the freeway beyond its existing footprint, requiring the state to use eminent domain to seize commercial and residential properties to make room for frontage roads and managed lanes. But perhaps one of the most crucial contributors to what has become a self-fulfilling highway-building bureaucracy can be found at the very beginning of the entire planning process itself: forecasting future transportation demand.

“We look at 2045, but we use today’s travel behavior and reasons for traveling as staying constant,” Feldt says. “I don’t think that will be the case, but we have no way of understanding what travel demand will be like in 2045, so we do the best we can.”

The state has traditionally chipped in very little to public transit, even though most Texans live in urban areas.

There are two fronts upon which Dallas must vie for college-educated young professionals. As the largest city in the North Texas region, Dallas and the towns around it must collectively compete against other urban areas. Yet Dallas-Fort Worth isn’t even among the top 40 metro areas with the highest share of millennials with college degrees, according to a Brookings Institution analysis of Census data. And North Texas isn’t just behind obvious millennial magnets like Boston and San Francisco. It also lags behind metros like Austin; Kansas City, Kansas; and Columbus, Ohio. Meanwhile, Dallas as a city also finds itself competing against the suburbs it once created for the kind of college-educated young workers who lure corporate headquarters, support businesses, and sustain government coffers.

The region as a whole may not be doing relatively well, but signs of successful progress have shot up in some areas. An analysis of Census data by the University of Virginia Demographics Research Group found that during redevelopment in Dallas’ urban core between 1990 and 2012, the share of college-educated residents—and per-capita incomes—in those neighborhoods rose dramatically higher than the average downtown areas in America’s 50 biggest metropolitan regions. Still, as state and regional transportation agencies spent the same period expanding North Texas’ ever-growing network of highways and toll roads to make farther commutes take less time, undeveloped land gave way to sprawling suburban neighborhoods that collectively saw their own above-average spikes in college-educated residents and per-capita incomes.

Does that mean educated millennials prefer dense, urban neighborhoods or more spacious suburbs? Well, it’s hard to tell because members of the up-and-coming generation have had to etch out their lives atop metropolitan areas that were built around the automobile long before they were born. So planners who use current behavior to predict future needs may assume more people don’t live within walking distance to work or don’t take transit to entertainment districts because they don’t want to, when the reality is that previous planners didn’t invest in sidewalks and rail lines that would make such options viable.

“We have legitimately not created the infrastructure that makes it the most convenient and makes it the most effective,” says Kyle Shelton, the director of strategic partnerships for Rice University’s Kinder Institute for Urban Research.

NCTOG employees act as planning staffers who simultaneously advise and take direction from the Regional Transportation Council, a 44-member body of elected and appointed officials who prioritize which projects get federal and state funds. In June of 2018, the RTC was scheduled to vote on Mobility 2045, which acts as the Dallas-Fort Worth area’s long-term transportation budget. And while highway construction projects are poised to get more money than rail expansions, sidewalks, and bike lanes combined, NCTCOG officials say they still face a $327 billion shortfall in what they need for the region’s roads. How did they get to that number?

“We assume that we’re going to remove all of the congestion,” Feldt says.

But that entails something that transportation and urban planning experts say is counterproductive: building even wider highway corridors. That approach typically just prompts more drivers to use the roadways, which only begins increasing congestion again in what becomes a never-ending cycle known as induced demand. Feldt admits it’s not a feasible solution.

“I don’t think you want to because it would be very ugly and very land-intensive,” he says.

So why spend the time to estimate the number at all? Because those alleged shortfalls are what local and regional officials use to persuade state lawmakers to provide more money and allow more financing mechanisms to pay for more roads. But isn’t that just a perpetuation of the problem?

“It is,” Feldt says.

Meanwhile, DART is embarking on plans to build a second downtown Dallas light-rail line, expand its urban streetcar system, overhaul its bus routes to improve lackluster reliability, and construct the suburban commuter Cotton Belt Rail Line to DFW Airport. Its plans to finance all of this rely on DART’s own sales tax revenues and federal loans and grants that must be divvied up between all of the nation’s mass-transit providers. The state has traditionally chipped in very little to public transit, even though most Texans live in urban areas.

“There’s zero and that’s the way it’s set up,” says Sue Bauman, who chairs the DART board and sits on the RTC. “I wish there was a mechanism, but there really isn’t.”

State Rep. Ron Simmons of Carrollton, who sits on the Texas House Transportation Committee, is pessimistic that lawmakers will start steering more state funds toward transit any time soon. “You’re not going to get passed in the Legislature money from the state for mass transit when you have such needs for road construction itself,” he says.

With no major geographic barriers like mountain chains or an ocean on the North Texas landscape, there are few natural obstacles to restrict the region’s sprawl. So cities like Plano and Frisco, former farming outposts that ballooned into massive suburbs, have become major job centers in their own right as employers cluster near where their workers live. And while NCTCOG and RTC are charged with planning for growth, their purview is mostly limited to transportation.

When it comes to regulating how developments are built, which can influence the kinds and amount of transportation infrastructure they need, cities hold the reins. And their officials typically focus on how development can increase their lifeblood: property taxes and sales tax revenues.

“They’re not going to put a limit on where they can grow and how they can grow,” Feldt says.

Simmons, the Carrollton lawmaker who also is a nonvoting member of NCTCOG’s executive board, says the situation highlights how cities greenlight developments and then later turn to transportation agencies for infrastructure funds to support the growth that follows. “That’s not a good way to do business,” he says.

But the redistribution of people farther out is only expected to continue. Between now and 2045, NCTCOG estimates the region will grow from 7.2 million to 11.2 million people. And 31.9 percent of those additional 4 million people are expected to live in Collin and Denton counties. To look at it another way, Dallas County housed 46.2 percent of the region’s population in 1990. That is projected to fall to 30.6 percent in 27 years.

The proposed solutions to the sprawl effectively spur—and subsidize—even more sprawl.

In addition to that $2.8 billion outer loop through Collin County’s northern and eastern outskirts, Mobility 2045 plans for $1.2 billion in toll revenues to cover the costs of widening Dallas North Tollway for its entire stretch through Collin County. Another $994 million will go toward expanding the road from U.S. Highway 380 to the Grayson County line, just a county’s length away from Oklahoma.

All the expanded suburban toll roads and widened freeways leading out of Dallas threaten to exacerbate the middle-class flight away from the urban core, which has left Dallas to grapple with growing income inequality, a housing stock mismatched for what residents want, and underperforming schools.

“We want suburbs to be successful, but we also want a strong core,” says Griggs, the Dallas councilman. “So much of this suburban growth has been at a cost and at the expense of the city of Dallas.”

Mobility 2045 calls for more than $33 billion for rail expansions and improved bus and paratransit service. That includes planned rail lines that would connect to Frisco, McKinney, Midlothian,

Cleburne, and Waxahachie, all of which are suburbs or rural county seats that don’t currently pay into any transit agencies. But more than $22 billion of the $33.3 billion budgeted for transit capital projects comes from public-private partnerships or a $10 fee on vehicle registrations or other funding mechanisms that do not yet exist and would likely require legislative approval.

Bauman is skeptical that either could get support from state lawmakers, who have spent minuscule amounts of money on transit agencies once they wrote legislation creating them. “I think they feel like by doing that, they’ve done their share,” she says.

NCTCOG’s highway construction plans are also predicated on revenues that don’t yet exist, although at a much smaller percentage. More than $7.2 billion in money needed to make all the highway construction a reality comes from the assumption that lawmakers will hike both state and federal gas tax rates twice in the next 28 years.

It’s a laughable thought.

Legislators may assume their constituents still love roads above all else, but they also know that voters hate increased taxes even more. Feldt says NCTCOG isn’t lobbying for gas tax rate increases. That line item in the budget is simply a placeholder for an expected increase in road money. “It’s reasonably prudent to assume we’re going to get some additional funding. We just don’t know where or how much, so we take our best guess and come up with stuff.”

But if transportation funds are so limited—especially when it comes to transit and other non-car-centric projects—what makes planners so confident that highways will get even more? “History has told us over the last 30 or 40 years somehow, some way we always get additional funding,” Feldt says.

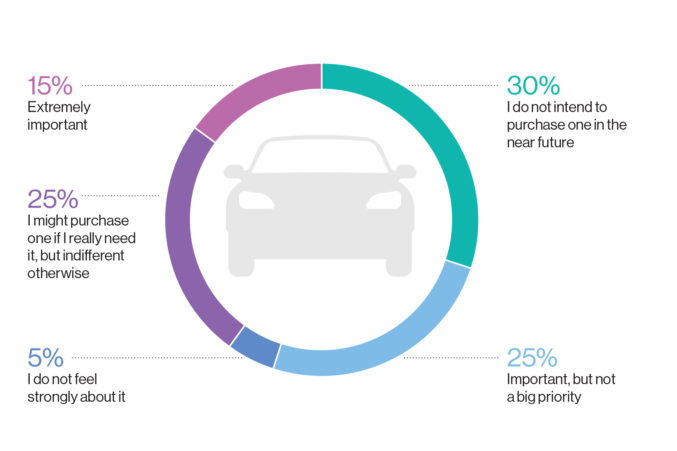

Source: Goldman Sachs, 2013

Feldt and other regional planners are quick to point out that much of the revenue that NCTCOG steers toward regional projects comes with federal and state restrictions on how it can be used. Fort Worth Councilwoman Ann Zadeh, who also sits on the RTC, says that’s part of the problem. She would like to see federal and state transportation agencies relax the restrictions on transportation money that send so many public funds to highways. “I would rather the money be available for what the local communities deem is the best way to handle our mobility needs,” she says.

Of course, that could increase competitiveness among RTC members for the funds. That body represents a wide swath of the state, and representatives from rural areas have far different priorities than suburban officials or urban leaders. Bauman, the DART chair, says she already sees that element at play as transit agencies try to work within confined funding streams as officials who want more roads have an easier time pouring more concrete to farther-flung locales.

“Sometimes it’s like our problems are our problems,” she says. “I’m not saying there’s not sympathy, but the vast majority of the members don’t have a rail issue to talk about.”

The disparate needs and priorities of RTC members are why Griggs would prefer that Dallas control its own fate without having to go through a regional planning body. “Dallas is such a major city, we should directly be receiving our federal funding to decide projects that will promote Dallas and put Dallas first,” he says.

For planners like Feldt, there’s pressure to accommodate the expected onslaught of people coming to suburban North Texas, even if there are cultural and technological shifts currently changing what people want out of their transportation networks. “Well, we’ve got to accommodate those people somehow,” he says.

But Griggs says the proposed solutions to the sprawl effectively spur—and subsidize—more sprawl. “That’s a big component of land use—the patterns they’re creating for how people move around,” he says.

And those patterns become the behavioral habits upon which future funding requests and long-term plans are based.

“It’s not sustainable,” Simmons says.

This story was produced in association with the Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization where Brandon Formby is the urban affairs reporter. Head to this link to buy a copy of the special issue and learn more about our July 11 urbanism symposium at the Dallas Museum of Art.