This piece is a feature from our special edition, Dallas and the New Urbanism. The magazine examines the successes and pitfalls of the urbanist movement in a region well known for its dependence on the automobile.

This piece is a feature from our special edition, Dallas and the New Urbanism. The magazine examines the successes and pitfalls of the urbanist movement in a region well known for its dependence on the automobile.One of my favorite books is a photographic chronicle of Dallas as it headed from the 19th into the 20th century.

Dallas was a rapidly growing city at the time, but what resonates now are the depictions of everything we’ve lost.

Beautiful buildings, an extensive streetcar network, a walkable city. The city’s ambition aligned with the built result. This could have been among the most beautiful cities in the country had we not erased it.

The reason that city disappeared is not the invention of the automobile. London, Paris, Rome, New York, and other great cities around the world have cars. But those cities were designed primarily for their residents. Cars were considered as another accommodation for people, just as horses and buggies had been and just as their subways and trolleys still are.

But Dallas did not just accommodate the automobile, it began to redesign itself for the automobile. With that shift, most prominently with the introduction of elevated interstate highways through our downtown, we transformed our central core from a city built for residents into a city built for commuters. With the interstates of the late 1960s, forced desegregation in the mid-1970s, and the localized and devastating oil and real estate collapse of the 1980s, the core of Dallas was emptied. The huge blacktop parking lots, ugly six-story garages, and wide one-way roads that dominate our downtown to this day were built to keep people commuting here. Instead, it drove people away. When we built for the commuter, we turned everyone into a commuter.

But then something unexpected happened. It seems people like living in cities.

So sporadically, fitfully, and organically, they began to build a new one. Someone called it Uptown, and the name stuck. It happened so quickly in a city so inured to commuter culture that the city’s government still doesn’t seem to grasp what happened, as witnessed by the narrow, obstacle-filled, and overflowing sidewalks of McKinney Avenue. In only a few years, Uptown—with its messy jumble of apartments, bars, new office buildings, and stores—is worth as much in tax value at $5.5 billion as downtown. If you build a place for residents, not for commuters, you will get them. And residents spend more money.

We are at a generational inflection point. We have the opportunity to rebuild our beautiful city.

But first, we need to reflect on what a city is.

If you build a city around a single technology and that technology becomes obsolete, your city fails.

Cities exist to facilitate social and economic exchange. They are the physical embodiment of economies and are fueled by human emotion: want and need. We want and need to exchange skills, goods, services, laughs, love, and, for perpetuation of the species, genes. So city form must be built to facilitate efficient exchange. Good city form increases productivity. It is why physicist Geoffrey West concluded that the bigger and denser cities get, all other things being equal, the more efficient they get. GDP grows exponentially with increased population density.

Cities are the market of all markets. Those that compete and succeed at a global level will empower the greatest percentage of their population to meet their needs.

“Elite projection” is a term defined by transit planner Jarrett Walker as the “belief, among relatively fortunate and influential people, that what those people find convenient or attractive is good for the society as a whole.” The original plans for and expansion of Dallas (and most cities) were largely driven by the elite. The train begins to rattle off the rails, though, when that vision disconnects from what everybody else in the city wants or needs. The leadership class fled the city core in the 1970s. They built a city for commuters because they were commuters.

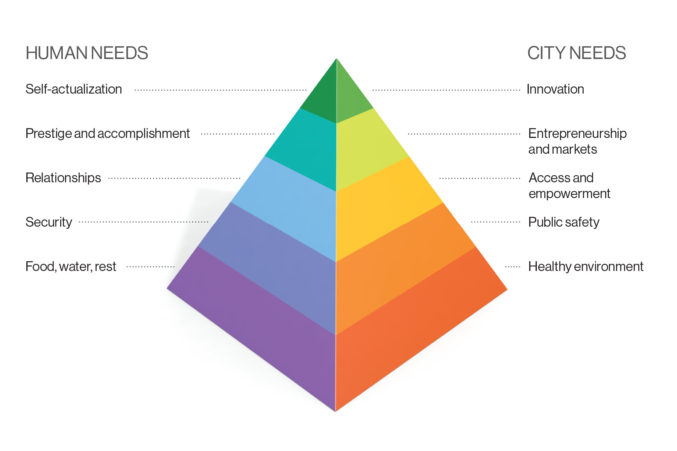

Abraham Maslow is most famous for his pyramidal hierarchy of needs, wherein he posits humans cannot satisfy higher-order needs until lower-order needs are met. At the base of the pyramid are basic needs: food, water, warmth, and rest. They are followed by security needs: safety and shelter. Only next is the psychological stuff: belonging and connectedness with others. The next highest is esteem, the feeling of accomplishment and purpose. At the top of the pyramid is self-actualization, the feeling of maximizing your potential.

The hierarchy of needs is a helpful lens for evaluating how cities operate. It is universal rather than individualized. Instead of internal needs, however, these needs are contextual, the surroundings in which I live. What is offered? What is missing?

If we created a similar pyramid of needs for cities, what would it look like? The base of the pyramid: a healthy environment defined by clean water, clean air, sanitation, and healthcare, followed by public safety. The next level at city scale, paralleling psychological needs at the individual level: access and empowerment provided by education and physical infrastructure. The next level related to esteem and accomplishment is entrepreneurship and access to capital and markets. At the top of the pyramid is innovation.

There are many possible definitions for what it means to be a “livable city.” I define livable by the percentage of the population that is able to meet its needs. If the city is safe, attractive, pleasurable, empowering, and equitable, people will want to live in it.

We have built a city based on a single transportation technology. I don’t care about driverless cars. That is not a new transportation technology. It’s just an improvement of an existing technology, and it’s still a problem. If you build a city around a single technology and that technology becomes obsolete, your city fails. If you build around a single technology and that technology can be afforded only by some, your city fails. If you build around one technology and you destroy all that was attractive and interesting in your city to make room for it, your city fails. If the infrastructure you built for that technology is burdensome to maintain, your city fails.

Elected officials rob Peter to pay Paul in a vicious cycle that bankrupts all other institutions. We now know that car-dependent infrastructure has, at best, a 30- to 40-year shelf life. All our major public highways were built in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Since it was not built nor financed to be maintained, it is a ticking time bomb.

You get what you measure, and today we measure vehicular delay. The result is that commuters take their property tax base and live outside the city. Eventually, they take their jobs and amenities with them. We have embraced physical mobility and left economic mobility to take care of itself. The collapse in median household income in Dallas County—from $62,000 two decades ago to $51,000 today—shows that it will not take care of itself. A minimum-wage single mother who is late to a job 10 or more miles away too many times gets fired. The broken used car she cannot afford to fix but is forced to own because public transit is too slow or irregular or far away does not figure into the equation. We can’t blame her employer for firing her. It’s not the company’s fault. But it is time to consider whether the fault is that she has to drive at all.

Copenhagen, Denmark; Vancouver, British Columbia; and Melbourne, Australia, are examples of cities that realized they were going broke building for cars. Meanwhile, their cities had become undesirable. The answer they arrived at, the only answer, was to rebuild around the only timeless form of transportation: walking. The great cities are still great because they never gave it up. Walking is what our species does.

A funny thing happens when you build a city for the pedestrian: all other forms of transportation function better. Walkability can be achieved only with narrower streets and wider sidewalks, which calm traffic; and with more people walking, fewer people are driving, which reduces congestion. More density creates a customer base for transit options, private and public. The city starts to work for everyone: the 8-year-old and the 80-year-old. Those with driver’s licenses and those without. Those who can afford a car and those who can’t. You offer choice. Choice empowers.

A funny thing happens when you build a city for the pedestrian: all other forms of transportation function better.

Rather than physical mobility, we should focus on accessibility. Meaning, instead of helping people drive 30 miles to jobs, we should bring jobs closer to housing and housing closer to jobs by building complete neighborhoods. The city of Portland, Oregon, codified the creation of complete neighborhoods as a stated target in public policy, insisting that all residents should have access to all of their daily needs, including frequent transit service, within a 20-minute walk. When we built for the commuter, we turned everyone into a commuter.

The proof is in our own pudding. The biggest complaint today about Uptown is that it is too expensive. Why is Uptown too expensive? Because so many people want to live there. You’ll find that true of every city in the world. The places that are inexpensive are the places that are empty. Only a few years ago Dallas was empty. It is still inexpensive compared with much of the world because we have not yet created enough places where people want to live.

Consider the possibility before us. New York is the cultural and commercial capital of the East, Chicago of the Midwest, and Los Angeles of the West. Which city is the one clear beacon of the South and Southwest: Miami? Atlanta? New Orleans? Houston? Surely, Austin wants to be.

Due to all of its geographic advantages, I think the commercial and cultural capital of the Southern United States will be Dallas. We sit at the nexus of the Deep South, the Midwest, and the Southwest, a magnet for each. I think Dallas will win because, despite all decisions against its own best interests over the past half-century, Dallas has continually failed upward.

The explosive growth of our region is mostly outward. All of metropolitan London could fit inside the boundaries of Dallas County. We have plenty of room for inward and upward growth. We have not even begun to take advantage of the density we can attain. Uptown is not dense at all by comparison to the richest places in the United States—Manhattan; Brooklyn; Boston; Washington, D.C.; San Francisco; to name the most obvious. Density creates ever more and more efficient exchange of goods and services. If a city is in the business of wealth creation, our greatest asset is the land beneath our feet.

We have competitors all around us. The suburbs saw the growth projections, the demographic trends, and the predicted generational shift years ago. They have responded, and they will benefit from their response. Competition is good. It breeds a variety of choices, which attracts even more people. Collin County, whose towns compete against each other and Dallas, is projected to double its population in the next 20 years. Legacy West could have more jobs than downtown Dallas.

That projection assumes the central core of Dallas will be static while Collin County grows. Whether Dallas will remain static depends on the choices we make. If we remove the obstacles, clear out the debris of the 1970s, and remold our infrastructure to enable people to live, work, and play within walking distance, Dallas can far outshine even the most progressive of its competitors. Their wealth creation is for the few. Our wealth creation is for the many. A walkable city removes the barrier to economic mobility. If our single mother can easily get to work so she can perform and keep her job, the entire city benefits from her contribution to the economy. A city truly is a commonwealth.

Dallas has four distinct advantages: history, culture, diversity, and land. History cannot be invented; it has to be lived. Culture derives from that lived experience, while diversity widens it. And we have lots of land. Southern Dallas is bigger than Plano. East Dallas is as big as Richardson.

We have in the past envied Houston for not being bound as Dallas is by a ring of suburbs. But it is the suburbs that are bound. The very word “suburban” implies less density. For them to densify too much would be to lose their very reason for being. In contrast, for Dallas to densify is to fulfill its promise.

Like the beautiful city of old, the city we lost and now have a chance to regain, we must begin to realign our built environment to match our promise. To my mind, there are four critical steps we can take now.

Dallas needs to take charge of its own transportation destiny

Historically, the two greatest threats to the economic well-being of downtown Dallas have been the Texas Department of Transportation and DART. City Hall was quiescent and at times complicit while elevated highways and a surface train line were run through its central core, decimating billions in potential real estate value and destroying whole neighborhoods.

No more.

The Dallas City Council made it very clear with its unanimous support for burying a necessary second downtown rail line that Dallas will no longer bow down meekly to track engineers. It should take an equally firm stand with the highway engineers.

By now, it should be apparent even to TxDOT that its usual methods are not only ruinous economically but also counterproductive. The $2.8 billion it spent in 2008 widening the Katy Freeway in Houston added 15 minutes to the morning commute and 23 minutes to the evening commute. It is a well-known phenomenon: adding lanes creates more congestion, not less. The concept is called “induced demand.” If one is looking for an example of waste in government, there is no better example. TxDOT treats every problem with an engineering solution. If a man owns only a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. Cities are more complex than that—and so is traffic, for that matter.

In Dallas, to its credit, TxDOT sought a better way. In 2016, for the first time, the department reached out to business, civic, and neighborhood groups to design improvements to the downtown loop based on value creation, livability, and reknitting the neighborhood fabric. The study, called CityMAP (for “master assessment process”), was met with wide acclaim because it showed the agency could be a force for good in encouraging investment and repopulation in downtown and southern Dallas.

But any study is only a beginning. Engineers will still be engineers. They were trained to see one part of a problem and to solve it. Only people who see the problem as a whole and who understand all of its moving parts can address how the city will move forward. Dallas needs its civic and political leadership to step up to the plate.

Use tolls not to create more tollways, but to finance options for transit

The opposition to more toll roads is understandable. Tolls in North Texas have been employed mostly to build more toll roads. For no reason whatsoever, Dallas residents are still paying $58 million annually in tolls on our portion of the Dallas North Tollway. That portion was constructed and its debt repaid decades ago.

But the opposition is too all-encompassing. Managed lanes, like the ones on LBJ and I-30, are useful de-congestion tools. Managing traffic is a behavioral science, not an engineering problem. If Gov. Greg Abbott is serious about prioritizing a reduction in traffic congestion, managed lanes are a good way to do it.

Instead of tolls going to build more toll roads, we could employ them for traffic reduction by using them to finance multimodal improvements: improved transit, bike lanes, and walkable neighborhood revitalization. In the case of the Dallas North Tollway, we do not need gubernatorial approval to begin. Dallas County is one of four counties, along with Collin, Denton, and Tarrant counties, that oversee NTTA. The organization is projected to have excess revenues over the next 10 years due to the high volume of the President George Bush Turnpike and Sam Rayburn Tollway, built with Dallas money. The authority could return that excess money to the counties for investment in their municipalities to meet an increasing demand for walkable infrastructure: widening sidewalks and laying more where we do not have them, recalibrating streets to calm traffic and encourage pedestrian use, burying power lines, and funding more neighborhood trolleys, streetcars, and other alternative transit.

A better option might be to sell NTTA. After years of investment, it is now a cash cow. The return on investment would be substantial. By using the money to reinvest in walkability, our cities would reap the long-term substantial gains in property tax values that have already been enjoyed by such cities as Washington, D.C., and Atlanta in the last decade, and which Dallas has already seen with Uptown and Bishop Arts.

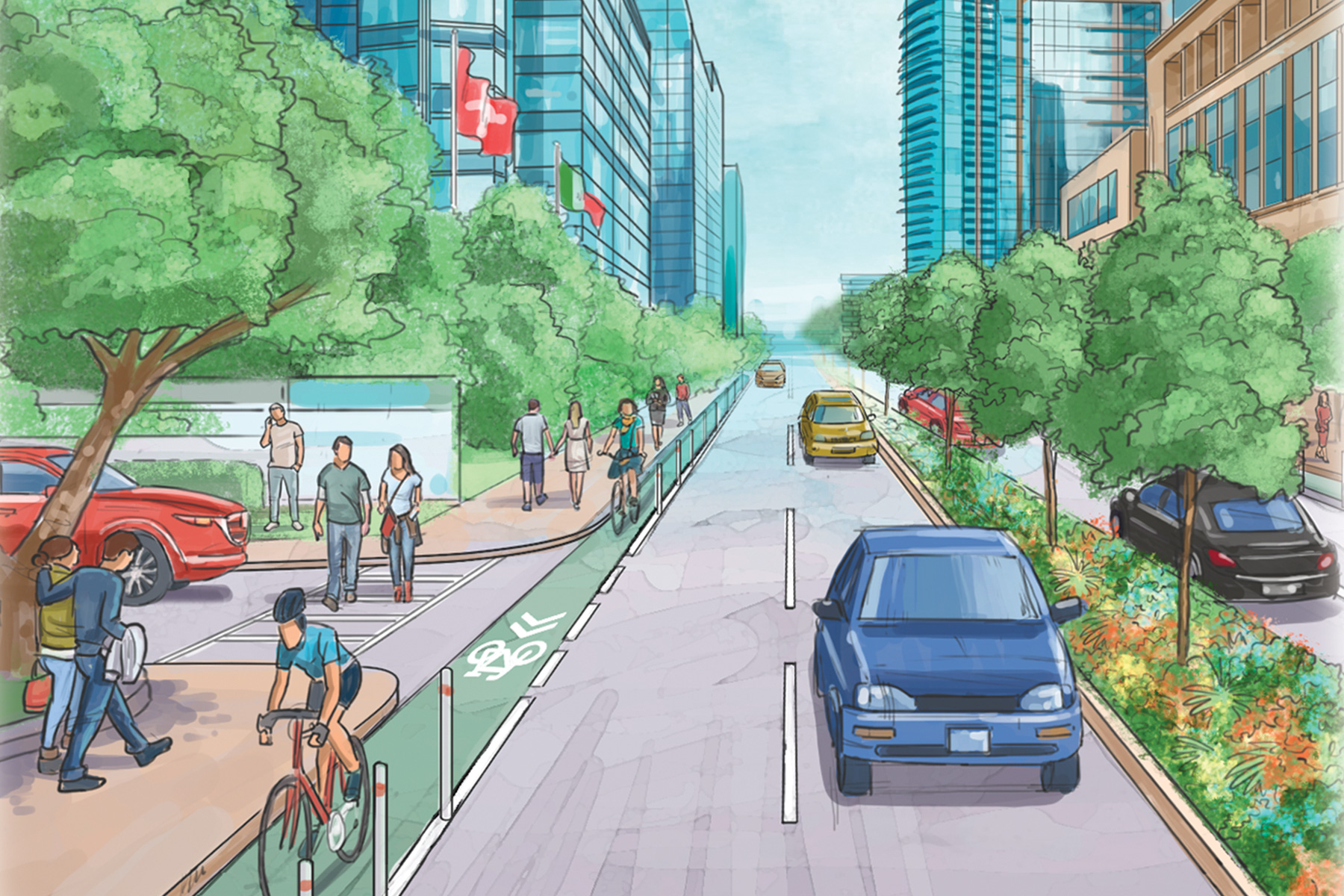

Extend our bike trails to bike lanes, creating a whole new people-power transit system

Ever since the success of the Katy Trail, Dallas has done a good job of building trails. The $30 million funding for connecting these trails from the latest bond program will only add to that success. But trails tend to have the same trip origin and destination. They are useful only for recreation rather than all the other trips we make in a day. Ironically, most of us also have to drive to them, loading our bikes into the back seat of our cars. We sometimes carry our bikes more than they carry us.

Our ever-growing trail system is an asset with a limited purpose, recreation. But we can extend its usefulness by turning it into its own mini transit system by connecting it with a network of protected on-street bike lanes.

The increasing use of bikes, personal and rental, is about to reach the level where they will become a hazard not only to bikers, but also to drivers and pedestrians when bikes swerve onto the sidewalk to avoid cars. So one issue is safety. We can turn a present safety hazard into an opportunity. Bikes are primarily used for destinations within a 3-mile radius. The more people who use them for those short trips, the fewer cars. Protected bike lanes make the streets safer for everyone.

Once safety is established—Maslow’s second tier—more people will use bikes not only for short trips, but also to go to work. We add transit as another purpose on top of recreation. The number of people riding their bikes to work in Denver has risen 57 percent since 2005 because that city invested in the infrastructure for cleaner, less congested travel.

Convert thoroughfares back to two-way streets

In the 1980s, trying to convince commuters to keep their jobs downtown, Dallas turned many of its downtown streets and access roads into one-way thoroughfares. The object was to speed people in and out. It was inconceivable that anyone would want to stay (after all, City Hall employees certainly didn’t want to stay, and if you saw downtown even up to the early 1990s, you understand why). They expected commuters to say, “Wow, now it’s so easy to drive! This is great!” But instead people began to say, “Why would I want to come downtown where there are only parking lots?” So people stopped coming—for jobs or for any reason. By 1994, downtown was so empty that one visitor famously wrote that he expected to see tumbleweeds rolling down the street.

Downtown today has 11,000 residents. Its residential units are near full capacity. Its four-lane, one-way thoroughfares such as Commerce and Elm are an anachronism and an embarrassment.

Cities are meant to be enjoyed, not from a car window but on the street. Lingering, having coffee at an outdoor cafe, looking into shop windows, and strolling to a business or barber appointment are what make streets great. Imagine trying to do any of those things on Harry Hines or McKinnon, the two huge, six-lane, one-way, west-side thoroughfares built as commuter connectors by razing Little Mexico back in the 1960s. Then they were extensions of the Dallas North Tollway, which is why drivers speed through them. Today, due to Uptown, Harwood, and Victory Park, they are part of the city, which is why the city has started to impose a laughable 35 mph speed limit on roads clearly signaling they were built for speed. Imagine, instead, a pair of two-way, tree-lined boulevards with broad sidewalks and protected bike lanes from Victory Park to Reverchon Park.

Cities are in the business of creating value and wealth for their residents. Wealth of experiences for residents creates more value by a factor so large that no commuter could possibly match it.

Head to this link to buy a copy of Dallas and the New Urbanism and learn more about our July 11 urbanism symposium at the Dallas Museum of Art.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Dallas’ most important news stories of the week, delivered to your inbox each Sunday.