When the 911 dispatcher comes on the line, Brenda Lazaro is already crying. She repeats: “Oh, my God! Oh, my God! Oh, my God!” Not knowing what the call is about, the dispatcher tries to calm her. He asks her where she is. She shrieks into the phone, “At the apartments!” Then: “Oh, my God! No, no, no, no!” The recording that starts at 11:30 pm that night, February 2, 2014, is a series of nightmarish screams and infuriating misunderstandings.

When the 911 dispatcher comes on the line, Brenda Lazaro is already crying. She repeats: “Oh, my God! Oh, my God! Oh, my God!” Not knowing what the call is about, the dispatcher tries to calm her. He asks her where she is. She shrieks into the phone, “At the apartments!” Then: “Oh, my God! No, no, no, no!” The recording that starts at 11:30 pm that night, February 2, 2014, is a series of nightmarish screams and infuriating misunderstandings.“Ma’am, I need you to calm down,” the dispatcher says sternly. By then, they’re nearly 30 seconds into the call. “Which apartments are you in?” He’s clearly asking for the name of the complex.

Brenda gulps air and shouts back, “Eight one three!” She repeats the apartment number twice before saying she’s near the corner of Belt Line Road and MacArthur Boulevard, in Coppell. She says she doesn’t know the name of the apartment complex. “Please!” she pleads. “Please tell me what to do!”

About a minute into the call, Brenda—who spent much of her childhood in Mexico and struggles with English verb tenses—explains why she dialed 911. “He’s shooting himself on the heart,” she screams. “And he’s dying right now!”

“Ma’am, I can’t understand you,” the dispatcher says. “I need you to take a deep breath.”

“He’s dying!” she says. “He shoot himself!”

Nearly 90 seconds into the call, she tries giving directions. The dispatcher asks if there’s any mail in the apartment, so she can read off the address. She says there isn’t.

Almost three minutes in, as the dispatcher is still trying to figure out which apartment complex she’s in, Brenda starts repeating her boyfriend’s name: “Jonathan? Jonathan?”

The dispatcher asks if he shot himself on purpose. First Brenda shouts, “No!” Then she corrects herself. “Yeah, he did it on purpose!”

The dispatcher asks where he shot himself, and she says she doesn’t know. “There’s too much blood,” she says. “I’m just pressing on it!”

Four minutes into the call, the dispatcher asks if she can go to a neighbor’s apartment to verify the address. “No,” she says. “I don’t want to leave him alone!”

After six minutes, the dispatcher tells her she needs to go outside and knock on a neighbor’s door. “Oh, my God,” she says. “I think he’s dead!”

“I need you to go now!” the dispatcher says. “Go now!”

Eight minutes into the call, she finds a neighbor to verify the name of her boyfriend’s complex, the Riverchase Apartments, and though the dispatcher tells Brenda to stay outside, she goes back into the bedroom and declares again: “He’s dead!”

A minute and a half later, the dispatcher, assuming Brenda discovered her boyfriend like this, asks her what she saw when she first walked in. “We were just having a discussion and we were just talking,” she says. “He just said that he loves me, and I didn’t believe him. He said he was gonna prove that he loves me.” She adds, “I didn’t know that he had a gun.”

When paramedics arrive, at approximately 11:40 pm, they find 27-year-old Jonathan Crews in his bed, under the covers up to his waist, with a gunshot wound to the left side of his chest. He is dead, slumped to his left, with both arms extended. The bullet, from his own SIG Sauer 9 mm, went through his heart, lungs, and liver before exiting the right side of his back, into the bed. The gun sits next to him, on top of his blanket.

Jonathan’s family explains to police on the scene that Jonathan had no history of depression, and, in fact, he recently started a new job that he liked and just moved into his own apartment. He was a meticulous, careful gun owner, drilled on firearm safety since he was a little boy.

But Brenda, 26, says it was suicide. She tells police that she spent the night with her boyfriend, watching TV and eating Chinese food and fighting about a woman named Emily. Brenda says she was at the foot of the bed, sitting on the floor, when Jonathan told her to cover her ears. She says that’s when she heard the gunshot.

Jonathan and Brenda met at Wu Yi Shaolin, a martial arts school in a Coppell strip mall just a few blocks from the Riverchase Apartments. Brenda was a teacher there and a close friend of Jonathan’s sister, Dani, who took classes at Wu Yi. Jonathan’s mom, Pam, also took classes there. Ever the respectful big brother, Jonathan asked Dani’s permission to date her friend.

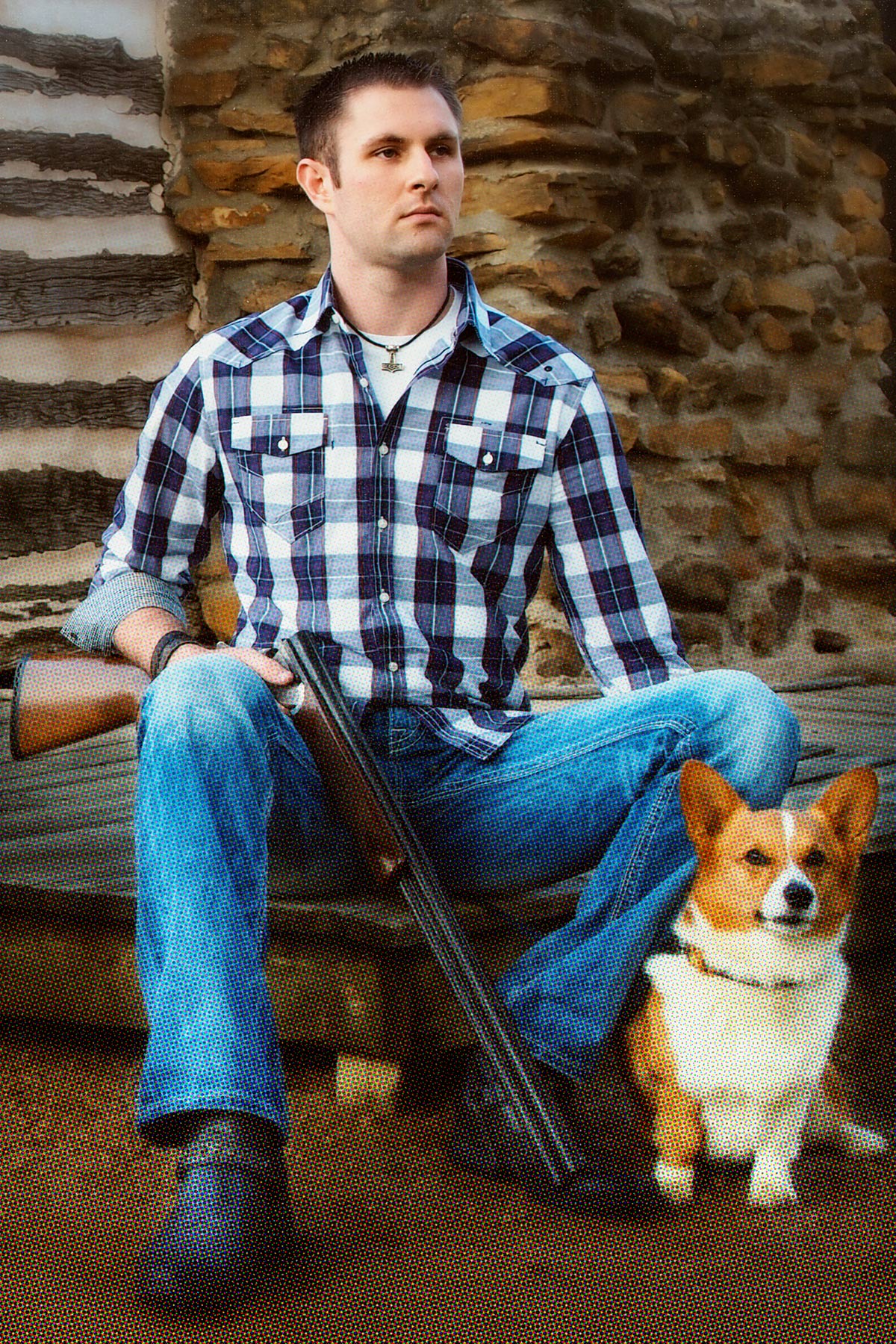

Jonathan and Brenda met at Wu Yi Shaolin, a martial arts school in a Coppell strip mall just a few blocks from the Riverchase Apartments. Brenda was a teacher there and a close friend of Jonathan’s sister, Dani, who took classes at Wu Yi. Jonathan’s mom, Pam, also took classes there. Ever the respectful big brother, Jonathan asked Dani’s permission to date her friend.Jonathan was born in California but grew up in Irving. Pam stayed home, raising her three kids. Their father, John, was a lawyer and a pastor at the nondenominational Heartland Church. Young Jonathan often visited his grandfather in Montana, where he learned to shoot pistols. He grew up to be a tall, gangly teenager. He played bass guitar and listened to Ozzy Osbourne and Green Day—until he learned his mom liked them, too. He was quiet with strangers and laid-back, with a quick smile.

Jacob Ramsey met Jonathan in ninth grade, and they were roommates for several years at Baylor. “I was a little bit jealous of him growing up,” Jacob says. “He was this super athletic, good-looking guy. And he had this ability to just always be this nice guy. Especially through college, I could just never get mad at him.”

Jonathan was a messy roommate and such a deep sleeper that he had to set three alarms to make sure he didn’t miss class—a traditional alarm clock, plus the alarm on his phone, plus another alarm that vibrated his pillow. Jacob says, “The fourth alarm was me hitting him in the head with my pillow.”

Jonathan had a handful of serious romances during and after college. His mom says he had “a pick-up-the-broken-baby-bird kind of thing” with women. His friends say he was a serial monogamist, sometimes trusting to a fault. “He was the type of guy who liked to be with somebody,” Jacob says. “He would always fall really hard and give the best of himself and a lot of money to a new relationship. He was always looking for a wife.”

When he dated a Muslim woman, Jonathan learned how to read and write some Urdu and bought a Quran. And when it was over, he wanted to keep things friendly, like he did with all of his ex-girlfriends, even the one who once drunkenly slapped him. “When he was done with someone, he was definitely done with them,” Jacob says. “But he always wanted to stay friends.”

In 2009, he graduated with a history degree—he named his dog Ulysses—then moved back to North Texas and worked at a Dillard’s, where he’d use his employee discount to buy his sister clothes. At his most recent job, as an operations director at an urgent care clinic, he organized a surprise baby shower for a co-worker. With the money from the new job, he rented the apartment in Riverchase, his first time living on his own.

Brenda Lazaro’s background is harder to gather. A man she dated for more than four years testified that she told him she was born at Parkland, in Dallas. But her sister, Isela Lazaro Garcia, testified that Brenda was born in Oregon. When she was 5 or so, Brenda’s family moved to Mexico, where her parents are from. She has told people that while she was in Mexico, she witnessed a murder—who and where has varied on different tellings. One of Brenda’s best friends says Brenda told her she was kidnapped with another girl and set free after the other girl was murdered.

When she was a teenager, her family moved to Irving, where her father works installing solar panels. Her ex-boyfriend says she told him she was raped in high school and had a rough home life. Several friends remember her telling them she was pregnant at various points, but she never gave birth. According to a profile on the Wu Yi website, she started tai chi and kung fu at North Lake College in the spring of 2006. She’s petite, with straight, jet-black hair and stark brown eyes. Henry Su, the owner of Wu Yi, has known her for more than a decade. He describes her as a hardworking, reliable employee. “She doesn’t say very much,” he said in a deposition, “but she’s appropriately friendly.”

After getting a Spanish degree from UTA, she worked as a substitute teacher and taught classes at Wu Yi in the evenings. In May 2013, she ended her four-year relationship, and in November of that year she started dating Jonathan. He told people that she understood him, that they were similar in ways he had a hard time describing. Her sister says Brenda was always excited when she came home from seeing Jonathan, that she often talked about marrying him and having kids.

Not long after the relationship started, Jacob and his girlfriend (now wife), Emily, went out to dinner with Jonathan and Brenda. The two couples met at a Chinese restaurant. Brenda barely said a word. At first, Jacob and Emily thought their friend’s new girlfriend was just introverted. Only later, Jacob says, did they learn why Brenda was being so quiet. “She was doing that because she didn’t like the fact that Emily hugged Jonathan,” Jacob says.

Facebook conversations from Jonathan’s computer and text exchanges from his phone show that Brenda was prone to fits of jealousy throughout the three months they dated. She dwelled for weeks on the single hug from Emily, bringing it up often in fights. When Jonathan told his mom about how jealous Brenda was getting, Pam said he should give her time. “Eventually she’ll see what a good guy you are, and she’ll see she can trust you,” she told her son.

“He said he was gonna prove that he loves me,” Brenda tells the 911 dispatcher. “I didn’t know that he had a gun.”

For Christmas that year, the Crews family took a trip to Germany. Jonathan sent Brenda photos and videos. She replied with questions about that hug from Emily or about women who’d liked his posts on Facebook. They argued over text deep into the night for several nights in a row. Around 3 am on Christmas morning, texts show, they came close to breaking up. But by 5 am he was back to reassuring her how much he loved her.

In January 2014, just a few weeks before he died, Jonathan and Brenda had another long argument that appears to be about one of Jonathan’s ex-girlfriends. The fight went on for days, both online and in person, even after he promised to break off all contact with his ex.

The arguments continued, and February 1, the day before he died, Jonathan told his sister, Dani, that he thought Brenda was going to make him choose between his relationship and his friendship with Emily, whom he’d known since college. He sent Dani a series of texts explaining that the way he saw it, he had four choices:

- Fight it and try to make it better which will probably never happen

- Choose Brenda

- Refuse to give up either and see if Brenda ends it

- End it with Brenda now

He told Dani that the first three options “all hold a strong likelihood of ending the relationship.” He concluded that breaking up on his own terms “limits/contains the damage.”

In the late morning of February 2, 2014, Jonathan sent Jacob a text asking if he wanted to get something to eat. Jacob and Emily went over to Jonathan’s new apartment. Before lunch, they took a tour. There wasn’t much furniture, but aside from a pizza box on the kitchen counter, the place was surprisingly clean.

In the late morning of February 2, 2014, Jonathan sent Jacob a text asking if he wanted to get something to eat. Jacob and Emily went over to Jonathan’s new apartment. Before lunch, they took a tour. There wasn’t much furniture, but aside from a pizza box on the kitchen counter, the place was surprisingly clean.Like Jonathan, Jacob grew up around guns. That day, Jacob looked at two of Jonathan’s guns: a new Tavor and the SIG Sauer. Jacob distinctly remembers that the second gun, the one that would later kill Jonathan, was stored in its own space in his dresser and that Jonathan kept it “ready to go,” meaning the magazine was in and a round was chambered.

At lunch, Jacob and Emily also noticed their friend acting oddly. “Looking back on it,” Jacob says, “he was a little awkward because he was afraid Brenda might find out that Emily was with us.”

The three friends went to Anamia’s Tex-Mex, one of Jonathan’s favorite restaurants. Just as the food arrived, Jonathan’s phone rang. It was Brenda.

“He was visibly nervous when he got the call,” Jacob says. “He knew Emily was there, and he knew what Brenda was gonna say.”

As Jonathan talked quietly to his girlfriend, Jacob and Emily looked at each other. They’d never seen their friend like this. Then Jonathan handed the phone to Emily and said Brenda wanted to talk to her.

“My wife has a bit of an attitude,” Jacob says. “She can be a bit of a boss lady. She doesn’t let people run over her. But when she got off the phone, she ran to the bathroom crying. I was kind of shocked.”

Emily says she tried to stay composed, but Brenda screamed at her. “I tried to say we’re just friends. When she met me, Jacob was there!” Emily says. “She just kept telling me I was a little girl, and I better stay away from her man.”

After the call, the three friends picked at their food and then left. Jonathan looked embarrassed and apologized to Emily.

“That’s it,” they remember him saying. “I’m going home and packing her bag.”

Back inside the apartment with his friends, Jonathan was uncharacteristically solemn. It was Super Bowl Sunday, and the couple invited him to forget about his relationship problems for a little while and join them at a party. He declined, though, and Jonathan’s college buddies left around 2 pm. Jacob and Emily both hugged him and told Jonathan that they loved him.

At 10:52 pm, Emily got a text from Jonathan’s phone. It read only: “I want to die.”

“That’s not the way Jonathan texted,” Emily says. “He’d send long messages or a bunch of messages, one after the other. Not just one short one.”

Roughly 40 minutes after that text was sent, Brenda called 911 to report the shooting.

After the Super Bowl, Pam and Dani decided to watch an episode of Downton Abbey. They were just sitting down when Dani’s phone rang. From a few feet away, Pam could hear Brenda screaming, “He’s dead!” Her first thought was that Jonathan must have been in a car accident, and Brenda was being overly dramatic. But then she heard Dani say something about Jonathan being shot.

After the Super Bowl, Pam and Dani decided to watch an episode of Downton Abbey. They were just sitting down when Dani’s phone rang. From a few feet away, Pam could hear Brenda screaming, “He’s dead!” Her first thought was that Jonathan must have been in a car accident, and Brenda was being overly dramatic. But then she heard Dani say something about Jonathan being shot.John was out the door and into the car before his wife Pam even had her pants on. Pam took a second car and got to the apartment complex a minute or so after her husband. She remembers some people gathered, hugging, and police officers in every direction. One told her she couldn’t enter the apartment.

Pam asked one of the officers there where Jonathan had been shot—in the head or chest? When she learned it was the chest, she thought that maybe someone had broken in and shot him. Then, in the chaos, she learned that Brenda had been in the apartment at the time. She learned that the police were questioning Brenda, and Pam assumed there’d be an arrest soon. She knew Jonathan wouldn’t shoot himself.

But then she heard that the police had tested for gunpowder residue on Brenda’s hands and let her go—which she assumed meant that Brenda couldn’t have done it.

That night, some people from the church came over to offer comfort. She doesn’t remember what time she eventually went to bed, but it was late. She hadn’t been sleeping long when her phone rang. It was Henry Su, the owner of the kung fu school. He told Pam that he’d just driven Brenda home from the police station and had talked with her about what had happened. He asked Pam if she wanted to hear it.

The story was essentially what Brenda had told the police. She’d gone to Jonathan’s apartment that afternoon. They’d fought off and on all evening. He’d told her to cover her ears and had shot himself. In this version, though, Pam remembers Henry telling her that Brenda said she was in the living room at the time of the shot, not at the foot of Jonathan’s bed. (Henry, in a deposition, denied saying that.)

None of this made sense to Pam. Nothing felt real. She didn’t know what to believe. She wanted to be strong, ready to take care of the rest of the family, so she told herself that she’d worry later about the details of what exactly had happened. They had a funeral to plan. Looking back now, she says, she “just wasn’t ready to think about any of that yet.”

The next morning, Brenda showed up at the Crews house. As the family mourned, she mourned with them. “I was probably taking care of her more than anyone,” Pam says. Brenda slept in Dani’s bed for the next three nights. Dani held her when she cried. Then one night Brenda slipped out without saying goodbye.

The family expected to see her at the viewing, but Brenda never showed up. She sent Dani a Facebook message about the funeral, asking if she could wear jeans and if she could ride with the family, but then she didn’t show up to the funeral either. She later sent Dani a message, upset that more wasn’t said at the funeral about her relationship with Jonathan.

“Why is it that your parents keep telling me they love me and understand what happened but they kept me completely out of this,” Brenda texted. “They never mentioned how happy he was with me or anything related with me. They included his best friends but not me.”

Pam didn’t know how to take this. “They had been dating for three months,” she says. “That’s not the kind of thing you talk about at a funeral.”

Still, she wasn’t suspicious of Brenda at the time. That didn’t come until a few days later, when she was talking to Jacob and Emily about Jonathan’s last day and that crazy phone call at lunch.

“I didn’t realize until then that she had a motive, too,” Pam says.

“We had hope all along,” Pam says. “Every time she didn’t show up at kung fu, I thought maybe they’d arrested her.”

Jonathan’s parents went to the Coppell police and explained that they had witnesses who could verify that their son was planning to break up with his girlfriend the night he died. Pam says detectives told her that they thought Brenda had done it and that they anticipated an arrest. She says the police asked the family to be patient. Pam was told to “act natural” when she interacted with Brenda at the kung fu school.

Court documents show that police investigated the incident as a possible murder. At the scene, they secured paper bags over Jonathan’s hands and photographed the apartment. They ran tests for gunpowder residue. Officers interviewed Brenda for hours that night—until Henry Su picked her up—and then they questioned her again in the days that followed.

But weeks passed without an arrest. Then months. The Dallas County medical examiner found that Jonathan did not have drugs or alcohol in his system and listed the cause of death as “undetermined.” The Crews family was told that detectives were waiting on test results, that they were trying to get a confession from Brenda or maybe one of her friends.

“We had hope all along,” Pam says. “You think they’re still interviewing people. You think they’re still gathering evidence. Every time she didn’t show up at kung fu, I thought maybe they’d arrested her.”

When Brenda did come to Wu Yi, Pam would have minor anxiety attacks. Then she tried to ignore Brenda. After a few months, Pam started watching and listening, hoping she’d overhear something that would crack the case. At some point, Pam and Brenda had an email exchange. Pam asked Brenda what happened that night, and in a series of long messages, Brenda wrote that Jonathan had been especially down in the three days before he died. She told Pam that Jonathan had been afraid of losing her. She said they fought the night of the shooting, but then they had watched TV and “fixed things” before he ordered food.

“We talked about how many kids we wanted to have and when,” Brenda wrote. “We talked about our plans and how happy we were with each other.”

She said that later that night Jonathan brought the argument back up and she went to the bathroom. She said when she came out, she sat on the floor at the foot of the bed and checked her phone. Brenda said Jonathan “said a lot of nice and sweet things to me” before telling her to cover her ears. Pam asked Brenda what Jonathan’s last words were. Brenda said he’d told her, “Baby, I love you so much. You are my world, and I will prove it to you.”

Brenda said she ran over to him and pressed on his chest as hard as she could to stop the bleeding. She described his last moments alive. “I was just looking at Jonathan because he was trying to say something and reach my hand,” Brenda wrote. “I couldn’t hold his hand because I was holding the phone with one hand and pressing on his chest with the other one. But he was looking at me very scared. I told him I love him and asked him not to leave me.”

The interaction left Pam feeling sick, and she barely communicated with Brenda after that.

Eventually the detectives on the case told Pam they were at an impasse. A few months later, she says, the case was reassigned to different detectives. They told her the case was solvable. “They asked us to give them six weeks to review all the evidence,” Pam says. “I was very hopeful again.” But then the new detectives reached the same conclusion, telling the family there wasn’t enough evidence to proceed.

As the second anniversary of Jonathan’s death neared, Pam and John began talking about filing a civil suit against Brenda for wrongful death. They thought that might at least give them a chance to look for more evidence.

“It’s not like we wanted anything from her,” Pam says. “We just wanted the truth to come out. She had all these fantastical stories and we wanted to get that story righted.”

When they met with an attorney, they were told that if they really wanted to learn the truth about what happened to their son, they were going to need a good private detective.

Sheila Wysocki’s unusual path to working as a PI got her featured on 20/20 and in both People and the Washington Post. When she was a student at SMU in the mid-’80s, her roommate was raped and murdered. The case went unsolved until, 20 years later, living in Nashville, Tennessee, as a stay-at-home mom, Sheila had a vision about her roommate and decided to become an investigator. She started with background checks and cheating spouses and worked her way up to missing persons and murder. At her urging, after hundreds of calls to the Dallas Police Department, her roommate’s case was reopened, and the evidence was retested. The DNA matched a rapist who had been out on parole at the time of the murder.

Sheila Wysocki’s unusual path to working as a PI got her featured on 20/20 and in both People and the Washington Post. When she was a student at SMU in the mid-’80s, her roommate was raped and murdered. The case went unsolved until, 20 years later, living in Nashville, Tennessee, as a stay-at-home mom, Sheila had a vision about her roommate and decided to become an investigator. She started with background checks and cheating spouses and worked her way up to missing persons and murder. At her urging, after hundreds of calls to the Dallas Police Department, her roommate’s case was reopened, and the evidence was retested. The DNA matched a rapist who had been out on parole at the time of the murder.Today, Sheila talks like a veteran detective, familiar with the unsettling details of far too many crime scenes. She works with a network of experts on everything from speech patterns to handwriting analysis. She’s 5-foot-5, with dark hair and glasses. She looks like a friend’s aunt or your kid’s teacher or that nice lady from church.

When she heard about the Crews story in 2015, she was intrigued. A few details struck her: the fact that men who commit suicide are far more likely to shoot themselves in the head, not the chest. The fact that Brenda’s story—that Jonathan had killed himself to prove his love for her—made no sense.

Sheila says she’s selective about which families she works with. “There’s a sound in the desperation in a mom’s voice,” she says. “Pam had that. It says, ‘You are my absolutely last hope.’ ”

Sheila agreed to take the case. She had the Crews family ask the Coppell police for Jonathan’s phone and computer. The phone screen was smashed, and its evidence envelope indicated it had been found between Jonathan’s mattress and box spring. Looking at his digital interactions in the weeks before he died, there were no indications he was depressed. But text conversations and Facebook messages revealed how often he and Brenda fought and how possessive she seemed to be.

Three weeks before the shooting, Brenda asked Jonathan via Facebook what he would do if they were to live together and get in a fight. “I would sleep,” he responded. “Just like I did tonight.”

With her staff, Sheila put together a list of everyone she wanted to talk to, anyone who might be a potential witness in a civil or criminal trial. Many of the people she spoke to were later deposed under oath. She interviewed Jonathan’s neighbor, Stephanie Mitchell, who remembered hearing a gunshot that night about 20 minutes before she heard someone knocking on her door. Mitchell would later testify that when she looked through her peephole, she saw Brenda.

Sheila talked to the manager of the Chinese food restaurant Jonathan had ordered from the night he died. Sheila says the manager remembered the driver that night overhearing a fight and having to knock several times before the door opened.

She found Brenda’s ex-boyfriend, Matthew Kirk, the man she’d dated for four years. He told her that Brenda had cut herself regularly during their relationship, that she’d pulled out her hair and slammed her head against a wall. He said that she’d been “very jealous.” In a deposition, he later testified that Brenda “got crazy whenever I went around any girl,” including his sister-in-law. He said Brenda didn’t even want him going to the hospital the day his niece was born. He said he went anyway and came home to find Brenda crying in his bathroom “and her hand was full of blood.” Matthew said she’d also threatened to kill his mother and that he’d called the police twice to have Brenda taken to a hospital.

“That girl ruined me and the relationship between me and my family,” he said, noting that after more than four years, she broke up with him in a text message.

Matthew also said that the morning after Jonathan was shot, Brenda came to his home. It was the first time he’d seen her in months. She was crying and asked him repeatedly, “Would you do anything for me?” When he said yes, she asked him to shoot her. He said no, and she asked him to give her a gun so she could shoot herself.

He testified in a deposition that Brenda told him that her boyfriend had been playing with a gun and accidentally shot himself in the head.

Sheila also went to see Brenda’s best friend, Karen Petree, at the school where she taught. Karen stopped the interview when she realized Sheila wasn’t a police officer, but she later testified that she’d gone camping with Brenda a few weeks after the shooting, and though they were alone for several days, Brenda never once mentioned Jonathan. She also testified that Brenda had told her she’d had an abortion the summer before the relationship with Jonathan began, and that Henry Su from the kung fu school had offered to pay for it. Henry denies this.

“Henry is like a father to us,” Karen testified. “He helps us out.”

Sheila wanted to know more about Henry and the kung fu school. To get information, she decided to go undercover and devised a scheme: she told them that she was involved with a nonprofit that worked with the victims of violent crime (which was true) and that she was looking for a martial arts school in Texas where she might send people for emotional and physical guidance (which was not true). When she arrived at the school to meet Henry, she had a folder with pictures of puppies on it.

“Do you know how disarming that is?” she says.

She went back to the school several times over a week. She talked to students and instructors—mostly about kung fu—and signed up for the first tai chi class of her life to observe the group dynamics. After class one night, she went to dinner with a small group that included Henry, still under the guise that she might bring the school new business. She thought it was strange that people there refer to themselves as “The Family.” The power dynamics reminded her of a cult, and it seemed as if people at the school would physically surround Brenda during breaks, “like they were protecting her,” Sheila says.

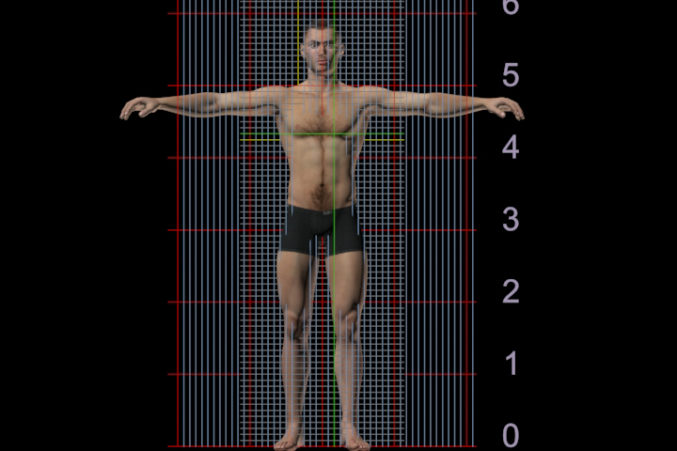

In addition to her interviews and surveillance, Sheila wanted to examine every bit of physical evidence in the case. She had the Crews family request all of the police documents, including the initial incident report, the autopsy report, and the gunpowder residue tests. Using that information, combined with photos from the scene, Sheila commissioned a video showing the trajectory of the bullet, from the left side of Jonathan’s chest to the right side of his back. Then she commissioned a computer animation that shows how difficult it would have been for Jonathan, who was right-handed, to pull the trigger, and another animation showing what it might look like if Brenda were the shooter. Sheila’s team created yet another video, demonstrating the heavy blowback or “kick” created by the SIG Sauer—strong enough, she theorizes, to at least knock the gun off the bed.

In addition to her interviews and surveillance, Sheila wanted to examine every bit of physical evidence in the case. She had the Crews family request all of the police documents, including the initial incident report, the autopsy report, and the gunpowder residue tests. Using that information, combined with photos from the scene, Sheila commissioned a video showing the trajectory of the bullet, from the left side of Jonathan’s chest to the right side of his back. Then she commissioned a computer animation that shows how difficult it would have been for Jonathan, who was right-handed, to pull the trigger, and another animation showing what it might look like if Brenda were the shooter. Sheila’s team created yet another video, demonstrating the heavy blowback or “kick” created by the SIG Sauer—strong enough, she theorizes, to at least knock the gun off the bed.Pam couldn’t decipher the gunpowder residue report once she finally saw it. Sheila explained that it shows Jonathan had residue on the tops of a few fingers on his right hand, but none on his right palm and none on his left hand. Brenda had residue on both sides of both hands and on her sweatshirt. No report mentions fingerprints on the gun or its magazine.

There’s another thing from the scene: reports and photos from the night of the shooting show that when the police arrived, they found the magazine out of the gun, in Jonathan’s tie drawer—not where Jacob had found the same gun “ready to go” a few hours earlier. “Jonathan was really into fashion,” Jacob says. “His ties were all carefully rolled, each one, to make sure they didn’t get wrinkled. He wouldn’t have put something with oil and lubricant on top of hundreds of dollars worth of ties.”

It’s not clear if the magazine was removed before or after the fatal bullet was fired, but because the magazine was out of the gun, it’s possible that whoever pulled the trigger didn’t know there was a round in the chamber. Jonathan was a competitive pistol shooter, taught the rules of gun safety since he was a boy, and also kept a few rifles at the apartment. Brenda’s ex-boyfriend testified that he took her to a range on two occasions to shoot handguns. “She didn’t know them that well,” he testified. “She didn’t know if it was loaded or not.”

An investigation narrative generated for the medical examiner’s office the morning after the shooting says that Jonathan had a history of depression and that he “was supposed to be taking anti-depression medication but was non-compliant.” It is unclear where that information came from. It certainly didn’t come from the Crews family. And when Sheila had Pam request Jonathan’s medical records, there was no mention of depression and no prescription for antidepressants. There was, however, a file showing that days before he died, Jonathan had had an injury to his right shoulder—which, Sheila contends, means he could not have fired the shot with his right hand, the only one with gunpowder residue on it.

“It would have been just about impossible if he didn’t have a hurt shoulder,” she says. “With that, it’s clear Jonathan didn’t do this.”

After reviewing all the evidence—the reports, the videos, notes from interviews and surveillance—Sheila developed a theory. She thinks that Jonathan did tell Brenda he wanted to break up and that they fought. She thinks that he got into bed and went to sleep, just like he said he would. She thinks that once Jonathan was asleep, Brenda sent that text message from his phone and then smashed it. She thinks Brenda got Jonathan’s gun, aimed at his heart, and pulled the trigger.

Sheila theorizes that the sound of the gun being cocked woke up Jonathan and that he may have grabbed at the gun with his right hand—explaining the gunpowder residue on that hand. She thinks Brenda ejected the magazine and hid it in the tie drawer, then waited before she called 911. She also thinks that Brenda was intentionally vague with the 911 dispatcher and intentionally slow to ask neighbors for the address because she wanted to make sure Jonathan was dead before anyone arrived.

Sheila told the Crews family that after working with her team of investigators for months, she was ready to take the evidence to the police. She put together a file and went to the Coppell Police Department. Pam and John hoped that this, finally, might be enough to prove that their son did not kill himself.

After all that, though, Sheila says, the Coppell police weren’t interested in anything she had to show them.

In the years since Jonathan’s death, Brenda Lazaro married and had a baby. She and her husband, Jason Kelly, both attend Wu Yi. Sheila saw them there when she was undercover and says he looked “like a puppy dog in love.” (Pam and Dani still participate in kung fu demonstrations, but they go to a different school.)

In the years since Jonathan’s death, Brenda Lazaro married and had a baby. She and her husband, Jason Kelly, both attend Wu Yi. Sheila saw them there when she was undercover and says he looked “like a puppy dog in love.” (Pam and Dani still participate in kung fu demonstrations, but they go to a different school.)In one deposition after another, Brenda’s friends from the kung fu school, including Henry Su, said they didn’t think she was capable of murder. Even the ex-boyfriend who called police on her and said she’d threatened to kill his mother testified that he didn’t believe Brenda would shoot someone. “I think she’s more of a talker than a doer,” he said.

Through her attorney, Brenda declined an interview request. He says she categorically denies any accusation of wrongdoing and has not wavered in her story.

A spokesperson for the Dallas County District Attorney says they handle cases only when there has been an arrest or the matter has been handed over by another agency, which she says has not happened.

A spokesperson for the Coppell police says the case is open but not active, and the department declined an interview for this story.

Pam says the entire experience with the Coppell police has left her feeling confused. “I want to think well of the police, so I don’t know what to think,” she says. “I’m normally a person who is very much pro-police. I think they get a bad shake and I don’t want to add to that. I’d like to think it’s a bunch of good people held back by budgetary restraints. I’d be real sad to think that I’m wrong.”

There’s a lot of evidence that points to Brenda, from her erratic history to Jonathan’s indications he planned to break up with her to the bullet’s trajectory and Jonathan’s shoulder injury. The neighbor, who didn’t know anyone involved, has no reason to lie when she says 20 minutes passed between the gunshot and the knock at her door. Brenda’s behavior after the shooting—skipping the funeral, asking her ex-boyfriend to kill her—seems bizarre.

But is any of that enough to send someone to prison? It’s possible the neighbor was mistaken about the time. It’s possible Brenda got gunpowder residue on her hands from pressing on Jonathan’s wound after the shot. A former medical examiner contacted last year by the Dallas Morning News said that, from the angle between the entrance wound and the exit wound, suicide couldn’t be ruled out conclusively.

And though Sheila’s theory is compelling, it’s not without problems. She argues that Brenda likely waited until Jonathan was dead before she called 911. But 50 seconds into the 911 call, a man seems to moan in the background. The sound occurs again around the 2:50 mark. Of course, the fact that it sounds like Jonathan is still alive when the call starts doesn’t mean he shot himself. It also doesn’t mean Brenda didn’t wait before calling 911.

Sheila says she doesn’t think that’s Jonathan on the tape. “Remember, there’s a dog there, too,” she says. “It’s not clear that she was even in the same room with him when she’s on the phone. I think she was in the living room.”

All of this would make for a difficult, complicated criminal prosecution. But the Crews family has filed a wrongful death lawsuit, which carries a lesser burden of proof. Their lawyers only have to show that a preponderance of the evidence indicates that Brenda is responsible for Jonathan’s death. The case is scheduled to go to trial later this year.

When Jonathan was a little boy, Pam remembers telling him: “Make yourself into what you want people to remember you by.” That’s what she thinks about when she considers giving up. “It’s a great wrong that’s been done,” she says. “There’s a lie swirling around Jonathan, and he has no opportunity to defend himself. If he had shot himself, I would be fine with that. There’s no shame around depression. But that’s not his story.”

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Dallas’ most important news stories of the week, delivered to your inbox each Sunday.