Near midnight, in an empty Cafe Brazil just east of SMU, Angela Hunt was about to alter the course of Dallas’ history. She laid out a proposal to two men sitting across from her, Lake Highlands City Council candidate Adam McGough and his campaign manager. Make a public statement, she asked them, one promising that, if elected, McGough would vote to withdraw city support for the construction of a six-lane toll road inside the Trinity River levees (“kill Alternative 3C,” in the parlance of the day). This was a big ask. McGough, a former chief of staff for Mayor Mike Rawlings, had never rejected the Rawlings-supported Trinity toll road plan. But now, in June of 2015, he was in a runoff with a tough candidate, Paul Reyes, a former John Carona staffer who had won a plurality of votes in the general election against McGough, 40.9 to 36.4 percent. The third-place candidate, James White, with little to his campaign other than a relentless anti-toll road message, had garnered more than 22 percent.

During her four terms on the Dallas City Council, from 2005 to 2013, Hunt often met with people skeptical of her stance against the proposed toll road. She would wheel around documents in a large luggagelike briefcase, hoping that facts would convince skeptics that the plan was a dumb, dangerous boondoggle. But she often found herself on a political island, ignored by her colleagues and the business community. As modern policymaking teaches us daily, facts rarely change a politician’s mind. As the workplace too often shows us, men in suits don’t like women telling them they’re wrong.

At this midnight meeting, however, Hunt didn’t bring her rolling briefcase. She didn’t ask McGough to take a stand because of facts, research, or the whispers of his heart. She was brokering a backroom deal to win the election for him.

I’ve secured James White’s support for you, she told them. If you come out against the toll road, he will tell his voters to support you. Without that backing, you’ll lose. With it, you have a shot.

A decision that seemed difficult became very simple. On Wednesday of that week, McGough issued a press release saying he wanted to withdraw from the 3C option. Later that day, White endorsed McGough. A few weeks later, McGough won his election by 36 votes.

In my first column for D Magazine, more than four years ago, I wrote about Hunt’s tenure as a council member. “To her critics,” I wrote, “Angela Hunt was an aginner, someone whose legacy is being merely ‘a disruptive grandstander,’ as one prominent North Dallas businessman put it to me.”

Since she left office, though, Hunt has become an expert at working behind the scenes with the same North Dallas suits—as well as the progressives who love her. She always outworked and out-wonked people on city issues. What’s remarkable is how, in the past four years, she has learned the art of persuasion. She didn’t call people out by name or deed to the media. She didn’t post angry late-night screeds on Facebook. She allowed former foes face-saving ways to change their minds. She wanted to win, not scold or take credit.

“What stands out to me is her dogged determination to get things done,” says state Rep. Rafael Anchia, someone who eventually came around to the idea that the toll road was bad for Dallas. “There were a lot of times when she could’ve given up, but she didn’t. She had the full weight of the establishment against her and she kept fighting. That’s what I admire the most.”

Examples abound. Here’s one that hasn’t been reported until now: a few months before the 2015 City Council elections, 10 past presidents of the Dallas chapter of the American Institute of Architects drafted an influential document comparing the road voters had approved with the runaway monster highway then being discussed. D Magazine described the contrast as “shocking.” A month later, the entire AIA chapter, which represents more than 2,000 people and 300 architectural firms, took the letter’s lead and came out against the toll road.

The letter’s effect was enormous in recasting the debate, and Hunt was the impetus behind it. She convinced past AIA Dallas president Bob Meckfessel to write the letter and worked with and through Meckfessel to get the other nine past presidents to join in. Then she never said a word about her role.

(Hunt declined comment on, but did not dispute, any specific scenario described here. She said only, “We were a remarkable group of grass-roots volunteers. I’m convinced it was the diversity of this coalition that made it possible to defeat the toll road.”)

To be fair, Meckfessel came to his decision to stop supporting the road on his own, in 2014. But Meckfessel—president at DSGN Associates and a board member at the Trinity Trust—needed guidance to use his standing to bring others around, to lead a movement of experts who’d changed their minds but craved political cover. Meckfessel’s was typical of the sort of heel-to-hero turn Hunt encouraged and facilitated. Recall that it was Meckfessel who in 2007 sat on a stage with then Mayor Tom Leppert at Temple Emanu-El in North Dallas and debated Hunt, arguing in favor of the toll road.

Much of Hunt’s ability to work behind the scenes has been strengthened by the fact that she’s no longer a public official. It’s easier for sympathetic City Hall staffers to reach out to citizen Hunt rather than Councilwoman Hunt and share information. When you’re having coffee with a private citizen, it feels like harmless gossip, not leaking information that would anger the mayor and pro-toll road council members.

But at the end of the day, Hunt won out because she combined a newfound ability to wheel, deal, and cajole with her thankless wonk work (done, it should be noted, as she juggled two young daughters and a day job as a zoning and land use lawyer at Munsch Hardt). Here’s another example that hasn’t before been public: CityMAP is the 351-page report from TxDOT that offers a vision for unlocking Dallas’ urban potential by redesigning or replacing the highways that choke the city. In a draft version, Hunt found, buried deep inside a footnote, a political bombshell. It showed that every version of the toll road—the big honking one, a proposed smaller one—would increase traffic in the downtown I-35 corridor, not alleviate it, as long promised. Hunt knew this information needed to be highlighted.

According to two sources, Hunt was able to convince Victor Vandergriff, one of five members of the Texas Transportation Commission, which oversees TxDOT, to take the footnoted material and put it in the main report, despite the pressure Vandergriff was under from pro-toll road forces on the commission and in Dallas. It was an important victory for Hunt, as it created a flashing red sign saying, “Don’t build this!”

Probably the most impressive example of her newfound power comes from her service on the Trinity Parkway Advisory Committee, a mayor-created group that reviewed the technical design of the toll road in the Alternative 3C plan. The committee had eight members, four of whom were comfortable with a big six- or eight-lane tolled highway (Jere Thompson, Ron Kirk, Lee Jackson, and Mary Ceverha) and four who were OK with the idea of a small, meandering boulevard (Hunt, Anchia, Meckfessel, and Councilwoman Sandy Greyson). Their job was to advise the Council on whether the technical design really would lead to the construction of the smaller boulevard. Understand the dynamic here. The highway lovers wanted the meetings held in private, with minimal public input. But the other four, while skeptical, also wanted to believe the committee was operating with good intentions. They wanted to find a compromise.

Hunt has become an expert at working behind the scenes with North Dallas suits—as well as the progressives who love her.

Take Anchia. (Disclosures: I recently took a job at Civitas Capital Group, where Anchia is a founding partner. I also worked on Hunt’s final City Council campaign. On most days, depending on what I write in these pages, both are friends.) Anchia had long been willing to help increase transparency around the toll road’s efforts. Years ago, when Rawlings and then City Manager Mary Suhm first talked of building a smaller version of the toll road, they were vague about whether they’d still eventually want a bigger version built. Hunt was convinced the smaller version was an attractive but dangerous Trojan horse, a means to shut up the toll road opposition while the city got concrete poured down in the Trinity, as a prelude to finally building the massive toll road.

But if she was going to attack the mayor’s persuasive argument—essentially, “Let’s agree on a small, meandering road”—she needed the feds to tell the truth: the city would be required to eventually build the big road per its federal submission. When she and other council members couldn’t get an answer out of the Army Corps of Engineers or the Federal Highway Administration, she turned to Anchia.

In early December 2014, ahead of Anchia’s hosting of a Trinity toll road town hall, Hunt asked him to send the feds the questions in his capacity as a public official. This time, they got answers—and Hunt’s fears were confirmed. The city absolutely would have to eventually build the bigger road under current conditions. Then Hunt arranged for a Skype call with her, Anchia, Meckfessel, Greyson, and Ian Lockwood, a national leader in sustainable transportation policy and urban design. His basic message: don’t believe them. They will want the big highway. Give them a foothold and you won’t be able to stop it.

It was a convincing message. Anchia agreed to co-author, with Hunt, a dissenting report that rejected the idea that 3C could ever be compatible with the vision of a park-first Trinity plan. If not the final nail in the Trinity coffin, the report was one of the nails. It signaled to Anchia’s more conservative business community base that it was OK to get onboard with killing the toll road.

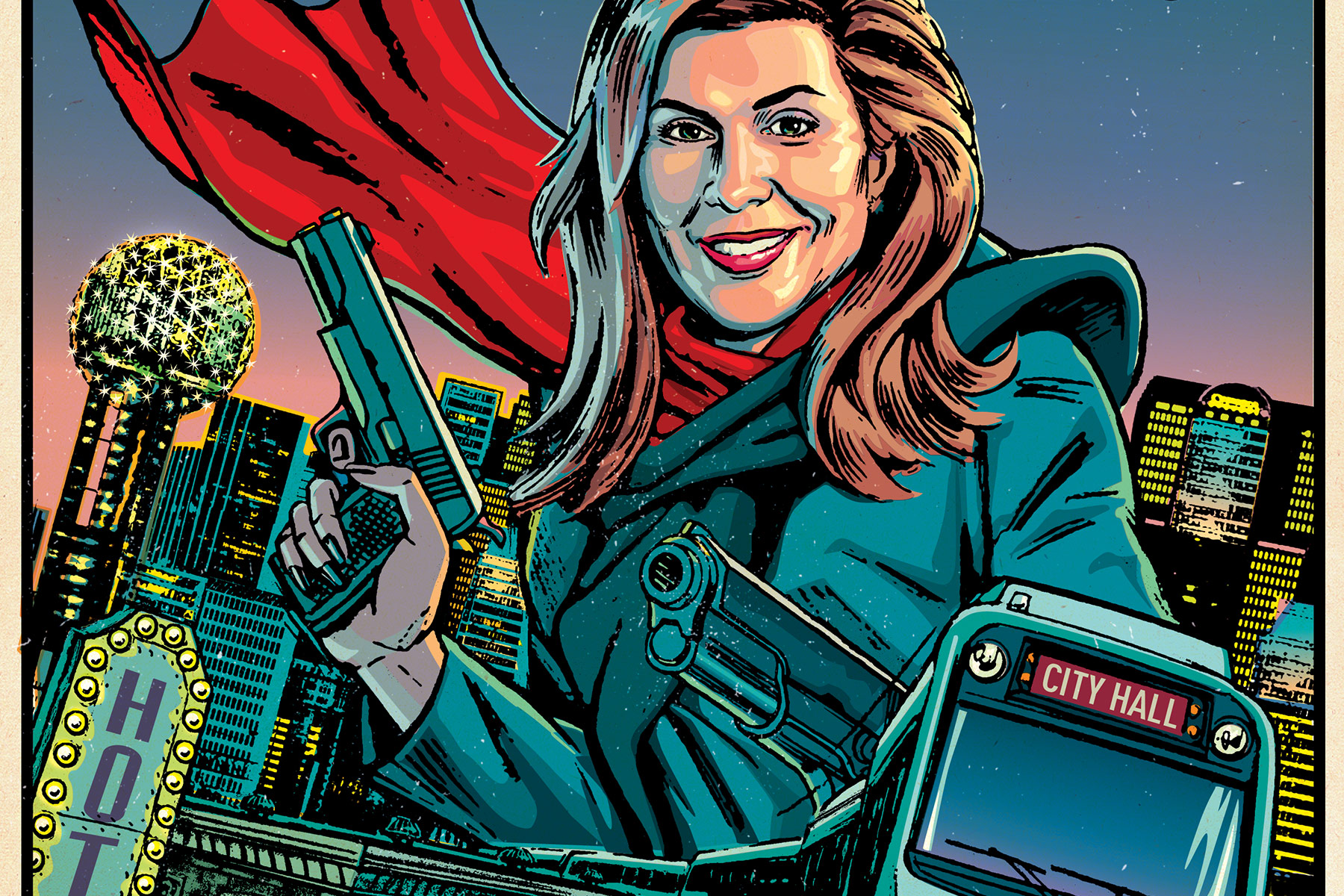

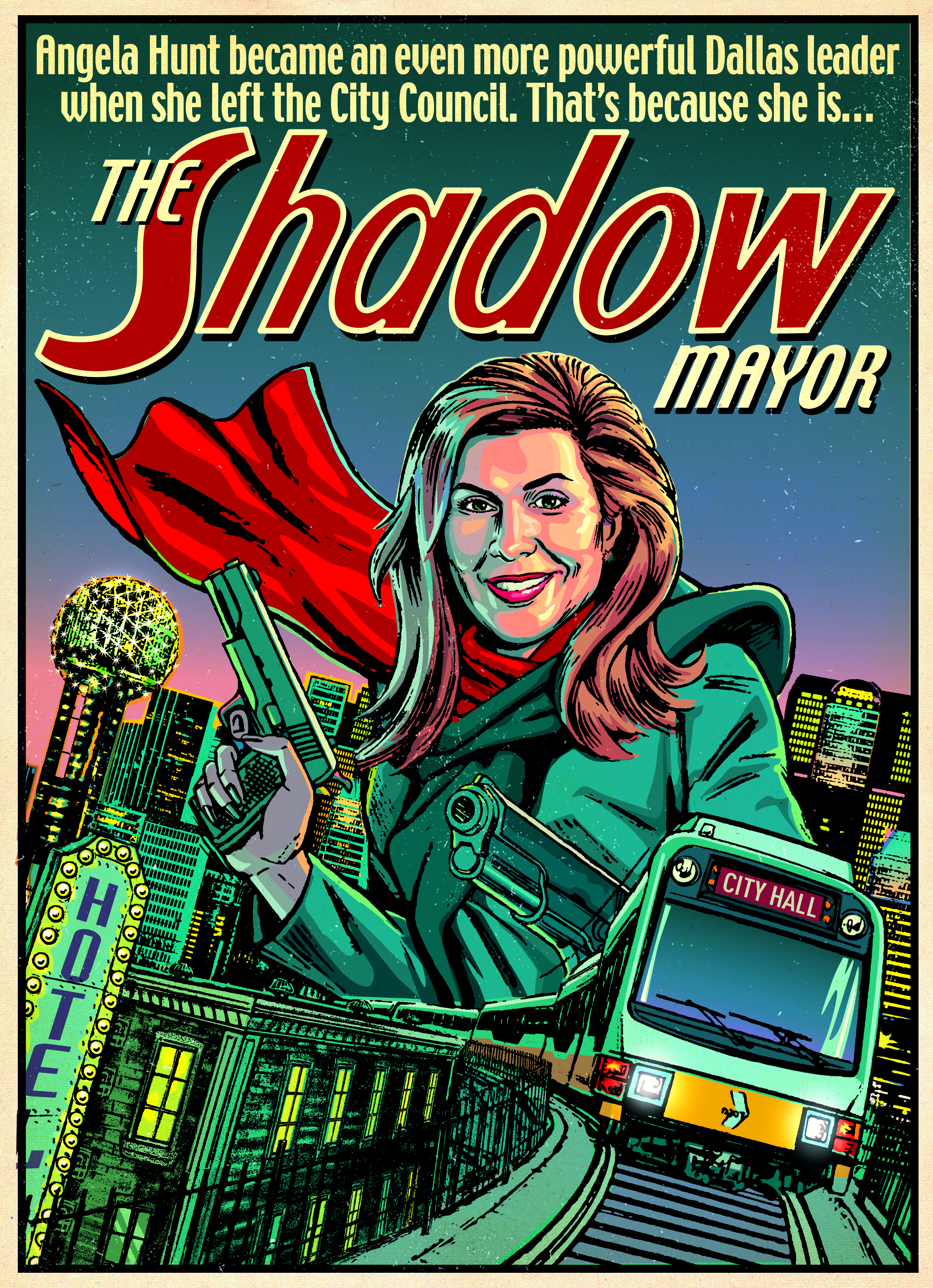

Hunt’s ability to find common ground and allow opponents a graceful way to come out against the toll road was key in just about every turning point of the road’s journey to the political graveyard. It proved that she could persuade the very people who once dismissed or damned her that she knew the way forward and that they should come along with her. In a way, for the past four years, she has operated as a shadow mayor. Seeing her newfound skills at work, one wonders if Hunt might be tempted to step into the light.

**

Editor’s note: an earlier version of this story said that Hunt had written Meckfessel’s letter. That was incorrect. Meckfessel and his team of past presidents wrote the letter. But the larger point (that Hunt drove the effort) is still accurate.