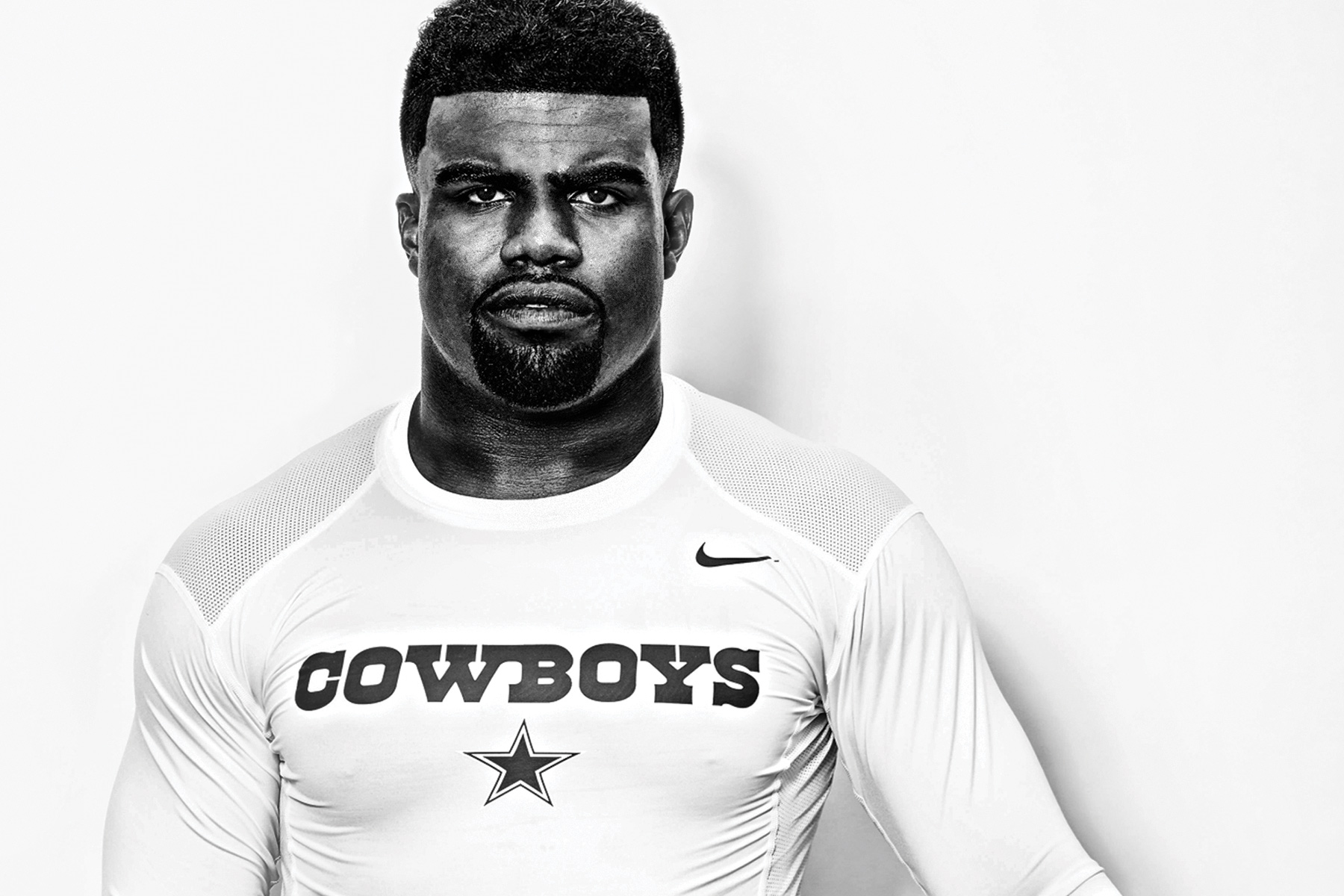

As I sat at a table in an empty conference room at Valley Ranch in June of last year, I fiddled with a Tupperware container of homemade buckeyes I had brought as a gift for Zeke Elliott. I was nervous. I grew up in Ohio, graduated from The Ohio State University, and had cheered as he’d won a national championship a year earlier. Maybe I shouldn’t have brought the buckeyes. He’d probably think it was creepy that some lady writer was bringing him homemade candy. But just as I was about to shove them back into my handbag, he walked into the room. Wearing a huge smile and without hesitation, he wrapped me in a bear hug before I could even introduce myself. He was still damp from his after-practice shower and smelled like soap and clean laundry. I felt like I was hugging an oversize puppy. I was instantly charmed.

Not even 21, a rookie who hadn’t yet played his first pro game, he seemed very much a kid. Our conversation was sometimes awkward. He mostly wanted to talk about football, but he also talked about his family, about his mother helping him do homework in the back seat of their car, about encouraging his little sister to run track, about his dog.

A month later, just days before my story would appear in D Magazine, TMZ reported that a woman had made allegations of domestic violence against Elliott. I had a moment of panic. I didn’t want to discount the victim, but it had to be a mistake. I made some phone calls to the Cowboys and to some friends in Columbus, Ohio, and this was the story as I understood it: Elliott had been out celebrating his birthday with friends at a bar in Columbus, when his ex-girlfriend, Tiffany Thompson, showed up. She called 911 and claimed that he had assaulted her in her car in the bar parking lot, but when police showed up, multiple witnesses said nothing had happened.

It made sense. Jealous ex-girlfriend of rising NFL star makes up a story in an effort at revenge or publicity. I breathed a sigh of relief, and then I didn’t think a whole lot more about it.

For the rest of the 2016 season, I made Cincinnati chili on game days in Elliott’s honor. My best friend bought me a t-shirt for Christmas with his cartoon face on it. I talked to our staff photographer, Elizabeth Lavin, about printing posters for my nephews of a shot she’d taken of him, shirt off and biceps flexed.

Then that spring, while on a Greenville Avenue bar rooftop on St. Patrick’s Day, Elliott pulled down a woman’s top to expose her breast. A couple months later, there were reports that he’d punched a DJ at an Uptown bar. Things weren’t looking good. I told Elizabeth I no longer wanted the posters.

But I still didn’t think there was any merit to the domestic violence allegations. Then, on August 11, more than a year after the alleged parking lot incident with Thompson, the NFL announced it was suspending Elliott for six games. For the first time, I realized I might have had the story completely wrong.

I messaged a friend back in Columbus, someone close to the situation. My friend wouldn’t tell me any details but pointed me to the city attorney’s website, noting that the entire police report had been online for nearly a year. There were seven links. I clicked on an audio file of an interview with Thompson. And I was stunned.

The more I listened to her interview with police, and the more I read the numerous witness statements, the less I understood why I hadn’t heard any of the details before. A couple of news stories had referenced the general outlines of the police report, but hardly any of this information had surfaced. No one had told the story about the days leading up to the parking lot incident. So I decided to write a chronological summary, more to make sense of it for myself than for anyone else.

What started as a brief blog post about the discovery of the police report turned into a 3,000-word description of Thompson’s allegations. When I posted it, I feared that one of the first comments would probably be from someone telling me that I was clueless and had missed the full story, already reported a year ago by the Dallas Morning News or Deadspin. But that never happened.

Instead, within a few hours, I was getting calls to appear on multiple sports radio and television shows, because, as it turns out, I wasn’t the only one who had had the story all wrong.

It was a surreal experience. Not only because I am not a sports reporter, but because I was having to explain, again and again, why I could no longer root for a fellow Buckeye, the man who had charmed me so completely, and why I found the details of Thompson’s account, as flawed a person as she might be, to be so convincing.

In her interview with police, Thompson never talks about what happened in the parking lot. Instead, she talks about the six days leading up to that, from the time she picked up Elliott at the airport on a Saturday afternoon until the time she showed up at the bar for his birthday party on Thursday night. She describes four times in the span of six days when he threatened her, punched her, threw her 117-pound frame against a wall, or strangled her until she couldn’t breathe.

But more telling to me was how she described the rest of the time. About how the violence would stop and he would act like nothing had happened, or he would apologize and say it was just “tough love.” In the recording, she’s not overly dramatic. She seems to take her time to answer the questions thoughtfully. She tears up at a couple of points, including while describing the most violent episode on Wednesday night. It was chilling. And for me, it changed everything.

I graduated from law school at Ohio State in 1997, when Elliott was 2 years old. My first job was as a Legal Aid attorney in a rural county outside of Columbus, handling mostly family law cases, almost all of which involved domestic violence. I read lots of police reports and talked to numerous witnesses. I interviewed victims and cross-examined abusers. And I learned a few things.

I learned that domestic violence never makes sense, but there’s often a pattern. Tension builds, as it might in any relationship—over money, or children, or fidelity. Arguments start. The victim may try to appease the abuser, or the victim may consciously or unconsciously escalate the fight to get it over with faster. Because when the tension peaks, the physical violence begins. The abuse is unpredictable and uncontrollable. The victim can’t, by doing things differently, avoid it. Then, as quickly as it starts, it stops, and what’s known as the honeymoon phase begins, full of protestations of love and remorse.

To many, Thompson’s account sounds unbelievable. And parts of it are. But to me, she was describing a classic cycle of abuse, one that she couldn’t see any way out of, except to finally call 911.

Now we are left with another story of a flawed hero. Elliott came to us larger than life. He was our first-round draft pick, our chosen one, our football savior. He came to us smiling and enthusiastic, snuggling with puppies to encourage SPCA adoptions and jumping into The Salvation Army’s red kettle to celebrate a touchdown. But you know what else I learned as a lawyer? Abusers are often exceptionally charming and polite.

Friends have asked me if I can still root for him. I can—just not on the field. Instead, I’m rooting for Elliott in real life. I’m rooting for him to stop making excuses. I’m rooting for him to get the help he needs. I’m rooting for him to grow up and be a better man.

At the end of September, my wife asked me to watch the Cowboys game against the Broncos with her. My sister, who lives in Denver, was watching with my 5-year-old nephew, and we texted back and forth as the game began. My wife made popcorn. But after the first couple of plays, I had to leave the room. I couldn’t bear to watch Elliott play.

Not even 21, a rookie who hadn’t yet played his first pro game, he seemed very much a kid. Our conversation was sometimes awkward. He mostly wanted to talk about football, but he also talked about his family, about his mother helping him do homework in the back seat of their car, about encouraging his little sister to run track, about his dog.

A month later, just days before my story would appear in D Magazine, TMZ reported that a woman had made allegations of domestic violence against Elliott. I had a moment of panic. I didn’t want to discount the victim, but it had to be a mistake. I made some phone calls to the Cowboys and to some friends in Columbus, Ohio, and this was the story as I understood it: Elliott had been out celebrating his birthday with friends at a bar in Columbus, when his ex-girlfriend, Tiffany Thompson, showed up. She called 911 and claimed that he had assaulted her in her car in the bar parking lot, but when police showed up, multiple witnesses said nothing had happened.

It made sense. Jealous ex-girlfriend of rising NFL star makes up a story in an effort at revenge or publicity. I breathed a sigh of relief, and then I didn’t think a whole lot more about it.

For the rest of the 2016 season, I made Cincinnati chili on game days in Elliott’s honor. My best friend bought me a t-shirt for Christmas with his cartoon face on it. I talked to our staff photographer, Elizabeth Lavin, about printing posters for my nephews of a shot she’d taken of him, shirt off and biceps flexed.

Then that spring, while on a Greenville Avenue bar rooftop on St. Patrick’s Day, Elliott pulled down a woman’s top to expose her breast. A couple months later, there were reports that he’d punched a DJ at an Uptown bar. Things weren’t looking good. I told Elizabeth I no longer wanted the posters.

Now we are left with another story of a flawed hero. Elliott came to us larger than life. He was our first-round draft pick, our chosen one, our football savior.

But I still didn’t think there was any merit to the domestic violence allegations. Then, on August 11, more than a year after the alleged parking lot incident with Thompson, the NFL announced it was suspending Elliott for six games. For the first time, I realized I might have had the story completely wrong.

I messaged a friend back in Columbus, someone close to the situation. My friend wouldn’t tell me any details but pointed me to the city attorney’s website, noting that the entire police report had been online for nearly a year. There were seven links. I clicked on an audio file of an interview with Thompson. And I was stunned.

The more I listened to her interview with police, and the more I read the numerous witness statements, the less I understood why I hadn’t heard any of the details before. A couple of news stories had referenced the general outlines of the police report, but hardly any of this information had surfaced. No one had told the story about the days leading up to the parking lot incident. So I decided to write a chronological summary, more to make sense of it for myself than for anyone else.

What started as a brief blog post about the discovery of the police report turned into a 3,000-word description of Thompson’s allegations. When I posted it, I feared that one of the first comments would probably be from someone telling me that I was clueless and had missed the full story, already reported a year ago by the Dallas Morning News or Deadspin. But that never happened.

Instead, within a few hours, I was getting calls to appear on multiple sports radio and television shows, because, as it turns out, I wasn’t the only one who had had the story all wrong.

It was a surreal experience. Not only because I am not a sports reporter, but because I was having to explain, again and again, why I could no longer root for a fellow Buckeye, the man who had charmed me so completely, and why I found the details of Thompson’s account, as flawed a person as she might be, to be so convincing.

In her interview with police, Thompson never talks about what happened in the parking lot. Instead, she talks about the six days leading up to that, from the time she picked up Elliott at the airport on a Saturday afternoon until the time she showed up at the bar for his birthday party on Thursday night. She describes four times in the span of six days when he threatened her, punched her, threw her 117-pound frame against a wall, or strangled her until she couldn’t breathe.

But more telling to me was how she described the rest of the time. About how the violence would stop and he would act like nothing had happened, or he would apologize and say it was just “tough love.” In the recording, she’s not overly dramatic. She seems to take her time to answer the questions thoughtfully. She tears up at a couple of points, including while describing the most violent episode on Wednesday night. It was chilling. And for me, it changed everything.

I graduated from law school at Ohio State in 1997, when Elliott was 2 years old. My first job was as a Legal Aid attorney in a rural county outside of Columbus, handling mostly family law cases, almost all of which involved domestic violence. I read lots of police reports and talked to numerous witnesses. I interviewed victims and cross-examined abusers. And I learned a few things.

I learned that domestic violence never makes sense, but there’s often a pattern. Tension builds, as it might in any relationship—over money, or children, or fidelity. Arguments start. The victim may try to appease the abuser, or the victim may consciously or unconsciously escalate the fight to get it over with faster. Because when the tension peaks, the physical violence begins. The abuse is unpredictable and uncontrollable. The victim can’t, by doing things differently, avoid it. Then, as quickly as it starts, it stops, and what’s known as the honeymoon phase begins, full of protestations of love and remorse.

To many, Thompson’s account sounds unbelievable. And parts of it are. But to me, she was describing a classic cycle of abuse, one that she couldn’t see any way out of, except to finally call 911.

Now we are left with another story of a flawed hero. Elliott came to us larger than life. He was our first-round draft pick, our chosen one, our football savior. He came to us smiling and enthusiastic, snuggling with puppies to encourage SPCA adoptions and jumping into The Salvation Army’s red kettle to celebrate a touchdown. But you know what else I learned as a lawyer? Abusers are often exceptionally charming and polite.

Friends have asked me if I can still root for him. I can—just not on the field. Instead, I’m rooting for Elliott in real life. I’m rooting for him to stop making excuses. I’m rooting for him to get the help he needs. I’m rooting for him to grow up and be a better man.

At the end of September, my wife asked me to watch the Cowboys game against the Broncos with her. My sister, who lives in Denver, was watching with my 5-year-old nephew, and we texted back and forth as the game began. My wife made popcorn. But after the first couple of plays, I had to leave the room. I couldn’t bear to watch Elliott play.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Dallas’ most important news stories of the week, delivered to your inbox each Sunday.