On July 8 of last year, the day after five police officers were shot and killed in downtown Dallas following a protest march, an interfaith prayer vigil was scheduled for noon at Thanks-Giving Square, just a few blocks from where the shooting had occurred. Downtown remained largely locked down, a fresh crime scene. The gunman, Micah Xavier Johnson, had been killed by police less than 10 hours earlier. As noon approached, Thanks-Giving Square was quiet, still, and hot, summer already at full boil. People filed in silently, dazed, until the sunken plaza was filled, some lining the bridge leading to the iconic corkscrew chapel on its northeast corner.

They were there—I was there—to try to make some sense of it all. Not just the previous night’s shootings, but the reason there was a protest march in the first place: the police killings of Alton Sterling in Louisiana and Philando Castile in Minnesota, specifically, but also the waves of violence that kept crashing against our shore.

Near the bridge, an all-hands lineup of city and state leaders, both religious and secular, semicircled behind a scarred wooden podium. Pastor Bryan Carter of Concord Church spoke first, followed by Dr. Jeff Warren of Park Cities Baptist. Dallas Police Chief David Brown was next, welcomed as a hero, then Bishop Kevin Farrell, State Sen. Royce West, and Rabbi David Stern of Temple Emanu-El. They were all greeted warmly and politely. The next speaker got a different reception.

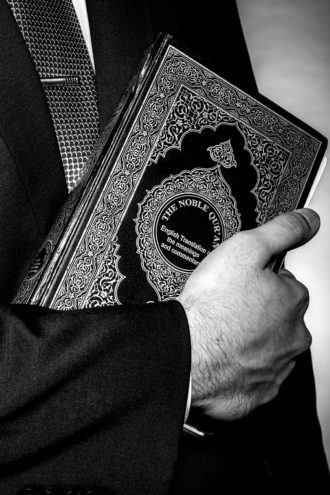

Closing his remarks, Stern introduced a man who had stood out among the group from the start, towering at 6-foot-5, his black kufi cap making him appear even taller: his “teacher and friend, the Imam Omar Suleiman.”

There was a stirring among the assembled as Suleiman—the resident scholar of the Valley Ranch Islamic Center in Irving, founder and president of the Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research in Las Colinas, and professor of Islamic studies at SMU—began rhythmically lobbing rhetorical questions, a murmured call and response usually found in the pews at a Pentecostal church. Perhaps it’s a stereotype, the solemn holy man, but it’s not what one generally expects from a Muslim imam.

“Mmm, he’s preaching,” said a woman near the front, closing her eyes, rocking gently. And Suleiman was, speaking without the aid of a prepared speech. No scripture. No parables.

“Mmm, he’s preaching,” said a woman near the front, closing her eyes, rocking gently. And Suleiman was, speaking without the aid of a prepared speech. No scripture. No parables.

“Is this what it takes for us to have to come together?”

Mm-hmm.

“Does it always have to be a tragedy?”

Mmm-hmmm.

“Does it always have to be murder?”

Preach.

“Does it always have to be terrorism?”

Aaaa-men.

“Does it always have to be”—a beat, mmm, so he could really lean into it—“that hatred forces us to love?”

Amen.

He didn’t show it, but the 30-year-old Suleiman was running on empty then. Ramadan had ended the day before the downtown ambush, a month of sunup-to-sundown fasting for Muslims. In the days prior, he’d been busy, helping with plans for the downtown march. And he’d been up all night. He was near the Old Red Courthouse, on his way to his car, when Johnson started firing. He saw the shots, saw officers fall. Amid the chaos, he found his friend the Rev. Dr. Michael W. Waters of Joy Tabernacle A.M.E. Church, and Waters’ wife, Yulise. They ran, ending up at Joy Tabernacle’s South Dallas sanctuary. There, they stayed up, watching the news and making plans for the vigil.

And so it went for the next several days. The enormity of it all wouldn’t hit Suleiman until later, when he was with his wife, Esraa, and their two kids on their usual post-Ramadan vacation, which had to be cut short. Sitting on a couch in a rented cabin in Austin, he started crying. “Holy crap,” he said to Esraa. “What just happened?”

At Thanks-Giving Square, Suleiman wasn’t thinking about himself. Couldn’t yet. “We don’t want an America of racism,” he said, finding his rhythm again. “We don’t want an America of brutality. We don’t want an America of terrorism. We don’t want an America of fear-mongering. We don’t want an America of division. We don’t want our hearts to be forced to come together—in a superficial way, at times—in the face of tragedy.”

Other speakers followed, bigger names, including Mayor Mike Rawlings and Bishop T.D. Jakes, who closed out the vigil. But Suleiman’s four minutes are what I left with, a life preserver when I didn’t realize how deep the water was. In that brief turn at Thanks-Giving Square—and again and again over the weeks and months since, in the middle of the night at DFW Airport and amid a community’s shared pain in a park in Balch Springs, in mosques and churches, in YouTube sermons and at protest marches—Suleiman showed that he is able to appeal to people of all religious beliefs, even those, like me, who don’t claim one. It has put him at the forefront of Dallas’ social justice movement and on the end of death threats from ISIS.

“I mean, look, he’s an ISIS target for a reason, because he really exemplifies the fault in that ISIS way of thinking, and knows that it’s not what Islam is about, and knows that there is a role for Islam in American culture and in Western society, and the best of what that can be,” says Chris Hamilton, a lawyer who worked alongside Suleiman over a long weekend at DFW Airport, at the protest against the Trump administration’s travel ban in January.

He is, to put it plainly, the religious leader Dallas needs right now.

Suleiman speaks often about how Muslims are only discussed in terms of national security, that it is part of how they are dehumanized, to be thought of as terrorists or potential terrorists and nothing more. Changing that discourse, pushing back against Islamophobia, is part of the Yaqeen Institute’s mission. So let me say, before we go any further, that Suleiman is basically a suburban dad with a very interesting and important job.

He takes his wife and their kids, 7-year-old May and 4-year-old Abdullah, to the Magic Kingdom in Orlando. He loves eating at Pei Wei and goes there whenever he’s near one. And he is a massive fan of the New Orleans Saints—like shrine-in-his-home huge. It was no accident that, when I saw him at Thanks-Giving Square, he was in Saints black and gold.

Though he has become a steady spiritual presence in Dallas, he is a fairly recent transplant. He move to North Texas five years ago, first to Richardson before settling in Irving, where the Valley Ranch masjid has a congregation of more than 3,000. Suleiman was raised in and around New Orleans, the son of a college chemistry professor (his father) and a poet (his mother), both born and raised in Palestine, before immigrating in the 1960s.

You can clearly see their influence on him. His father wasn’t clergy, but he did deliver sermons at the mosque on occasion. Both his parents instilled in him a deep need to be involved, with his community and the world beyond it. They took in Bosnians running from war and gave their car to Somali refugees. His mother wrote poems about the oppressed around the world, and his father helped with local political campaigns. They brought him to protests. His father had him swinging a hammer for Habitat for Humanity when he was 8 years old.

In this environment, Suleiman was expected to grow up quickly, and he did, quite literally. He was 6-foot-2 when he was in the seventh grade, not needing the lift from the Timberlands he wore everywhere. He looked like a man. Maybe the group of Ku Klux Klan members that jumped him as he was walking through a parking complex, beating him with brass knuckles, thought he already was.

His ethnicity separated him from his classmates at the all-black school he attended almost as much as his early growth spurt did. But it was mostly fine because, as he says, “people are racially ambiguous enough in Louisiana” that a Palestinian kid could pass for something else. “I was Creole for most of my life,” Suleiman says.

He grew early in his faith as well. He began delivering sermons at his mosque when he was 17, and he also embarked on a deeper study of Islam, earning his ijazahs, certifications to allow him to serve a congregation as an imam.

He needed to be ready. On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina made landfall on the Louisiana coast. He was in Baton Rouge when Katrina arrived, having left his New Orleans apartment behind as the storm neared—forever, as it turned out. He lost everything he had, which wasn’t much. He came home anyway, as soon as he could, when the stench of dead bodies could still be smelled from as far away as LaPlace, 20 minutes out. Before long, Suleiman was at the heart of the recovery effort, physically—he got a FEMA badge from ICNA Relief USA’s Muslims for Humanity project—and spiritually. His parents molded him for this kind of life of involvement, both in mind and body, but Katrina was the forge that cast him into iron.

He saw it wasn’t enough, or sometimes even right, to talk to people about God. He needed to show them what God’s work looks like.

When he returned to New Orleans, there were no imams left. He filled the void, at 19 years old, taking over at the city’s largest mosque—Masjid Abu Bakr Al Siddiq—and leading prayers at as many as seven others, presiding over marriages, divorces, funerals. Sometimes, during Ramadan, he’d rush from one to another, delivering sermons back to back to back. It was a volunteer assignment that turned permanent. Another growth spurt.

Along with everything else that was going on, the water swept away long-standing divisions in New Orleans’ faith community. Churches shared spaces with other churches out of necessity. A Reform temple took in a congregation of Orthodox Jews after their synagogue was destroyed. Suleiman found himself mediating disputes between older rabbis over kosher burgers. Navigating those often tricky relationships, he learned how different faiths could work together. He also learned they could only do so much.

“I will never forget these words,” he says. “There was an evacuee that came from the Superdome that said, ‘I feel like I’ve been spiritually molested.’ And she said that because of all the preachers that were going in there and telling her about God at the time, instead of helping her out. Kind of trying to take advantage of her vulnerability. And that was a common complaint that we had. Hearing those words—spiritual molestation—it was like, Wow, is this what we do?”

He saw it wasn’t enough, or sometimes even right, to talk to people about God. He needed to show them what God’s work looks like. As a director for the Muslims for Humanity project, he arranged to rent every apartment he could find in Baton Rouge, found the people in the most desperate living situations, and gave them a new home, four months’ rent fully paid. He kept gutting houses, working alongside members from Catholic Charities, seeing a level of neglect he can still barely talk about. They did this for years.

In 2008, when the Klan burned crosses on the lawns of black families in white neighborhoods, he didn’t just offer thoughts and prayers. He joined Rabbi Bob Loewy from Congregation Gates of Prayer and other clergy and went out and pulled those crosses from the ground.

The East Jefferson Interfaith Clergy Association grew out of that effort. It was big on dialogue, bigger on action. On the 10th anniversary of 9/11, they took their congregations to Kenner, a suburb of New Orleans, and spent the day doing a full cleanup of the Rivertown area, which had never recovered from Katrina, re-striping roads, painting buildings, planting bushes, hauling away trash. Then, because it was New Orleans, they all went back to Suleiman’s mosque for kosher and halal gumbo.

During the six years he spent as imam at Masjid Abu Bakr Al Siddiq, Suleiman also fulfilled chaplain services for his beloved New Orleans Saints, including during their 2010 Super Bowl season. He married Esraa in 2007; his daughter May was born a few years later. His work did not go unnoticed—the New Orleans City Council gave him its Outstanding Civic Achievement award in 2010—and his profile grew within the national Muslim community, calling for him to speak at events around the country. It wasn’t all heartbreak.

In 2012, with New Orleans and his congregation stabilized, and the East Jefferson Interfaith Clergy Association moving ahead, Suleiman was ready for a new challenge. He wanted to stay in the South—“I’m a Southern boy,” he says—and his travel schedule meant he needed easy access to an airport. So he came to Dallas.

On the afternoon of January 28, when news broke that travelers were being detained at DFW Airport, after President Donald Trump signed an executive order that essentially closed the U.S. border to seven Muslim-majority countries, Suleiman was playing football in a park. It was the same park he was playing football in when he learned of the shootings at an exhibition in Garland featuring cartoon images of the Prophet Muhammad.

“I was like, I’m not playing football in this park anymore,” Suleiman says. “Bad stuff happens.”

He pulled out his phone and sent word to his 1.2 million Facebook friends and 186,000 followers on Twitter: everyone head to the airport now.

By that evening, there were well over 1,000 people standing shoulder to shoulder in Terminal D, home to DFW’s international gates, all ages, races, and religions represented. More than 100 lawyers showed up to offer their services, pro bono. And there they stayed, all night Saturday, all day Sunday, chanting, never letting up.

“It became like a party at some point,” Suleiman says. “They started singing Ludacris songs and stuff like that. People were determined and people were optimistic. So there wasn’t despair there.”

Despite the high spirits of the crowd—the impromptu “Move Trump! Get out the way!” remix of Ludacris, especially—it was still a fraught time, with lives hanging in the balance. Suleiman was there for justice, helping negotiate with airport personnel, relaying updates when he could, and he was there for his people.

Eric Folkerth, the pastor at Northaven United Methodist, remembers a moment from late Saturday night, around midnight. Suleiman decided it was time for the late night prayer, Salatul Layl, and led a group of Muslims down a hall, away from the other protesters. “And I was just so moved by that,” Folkerth says, “that in the midst of this very, very stressful, tense time of protest, he still managed to lead people in a moment of calm and prayer.”

Monday evening, after most of the detainees had been released, Suleiman spoke at a candlelight vigil at Thanks-Giving Square. Again, the plaza had filled to the stone walls around the perimeter, the bridge to the chapel teeming with supporters. And once more, the stress and sleeplessness of the previous hours and days did not seem to weigh on him.

“You might tell me to go back home,” he said early on, before breaking into a big smile, “and I would tell you I’m from New Orleans, Louisiana, and I love it very much.”

There was more force from him that night than there had been back in July, but no anger. He was powerful but composed, a boxer on his toes flicking out jabs as he found the thread that connected it all: Japanese internment during World War II and the United States’ rejection of Jewish refugees, how dehumanization allows for Mexicans to be spoken of as rapists and black people as thugs, the need to see each other as human beings. He may have been confronted with fear and suspicion, but he would not give into it.

“Let me say to you that Donald Trump will never make me hate you,” he said. “And I hope that no politician will ever make you hate me.”

As he spoke, he was flanked by his Faith Forward Dallas co-chairs, the Rev. Dr. Michael Waters and Rabbi Nancy Kasten, which wasn’t unusual. They had been together often over the past two years, since the interfaith group of clergy (similar in spirit to the organization Suleiman had helped build in New Orleans) was founded, and even before that. They tended to show up at the same places for the same reasons, eager to reclaim what Waters calls “their birthright”: America’s “very long tradition of clerical resistance.”

Faith Forward Dallas coalesced after the shootings at Charleston’s Emanuel A.M.E. Church, in June 2015, when they came together to support Waters, who lost friends that day. Since then, they have stood together in Irving when armed protesters showed up in front of Suleiman’s mosque, in Oak Lawn in solidarity with the LGBTQ community after the Pulse nightclub attack, in South Dallas to offer aid and comfort to victims of gun violence.

But it’s not just that. They visit each other’s congregations, for sermons or special discussions, focusing on the part of the Venn diagram where their faiths overlap.

“In many ways, I think that the Texas community has come to anticipate our presence, our voice, and our leadership,” Waters says, “not just in the midst of tragedy or turmoil, but also to serve as a vision of what is possible in terms of peaceable community and intersectionality.”

They knew each other before Faith Forward, or at least knew of each other—Kasten remembers talking about Suleiman with his former colleague Rabbi Loewy on a bus in Jerusalem—but now they have grown close. When Suleiman sees Dr. Andy Stoker, senior minister at First United Methodist and another member, they always say “I love you” to each other.

“This is not some superficial clergy-level dialogue that is kumbaya, that ignores the great divisions in society,” Suleiman says. “This is a group of people that deeply love each other, see each other daily, whose families know each other, who speak to the issues that are important to the millennials and pre-millennials.”

In a meeting not long ago, Suleiman noticed just how much Faith Forward had transcended its origins, its purpose, even. It felt like a true family to him, like New Orleans again. It felt like home.

Growing up in New Orleans, Suleiman was never singled out for his religion, if only because he didn’t make it a point to let his friends or his teammates on the basketball team know he was Muslim. To be honest, he admits, he was struggling with the idea that he actually was.

Suleiman’s mother was sick a lot, spending his first two decades in and out of hospitals. She had cancer, undergoing chemotherapy twice, and four strokes. The first three left her partially deaf and unable to speak properly. The fourth took her life in September 2007. Suleiman says his mother’s condition left him searching. “I could not reconcile God with that,” he says.

He considered himself agnostic for a time. He went to synagogues, churches, mosques, investigating all possibilities. He read the Bible cover to cover when he was in middle school. Finally, he found his way back: “I just felt comfortable with Islam,” he says.

But that time spent away still serves him.

“My experience with religions allowed me to always sort of have a love and appreciation for people of other faiths and how they developed, how they came to their conclusions,” Suleiman says. “Because I could see myself coming to that conclusion as well, right?”

Because of that, he is able to get to the humanity at the core of all religions.

“He expresses himself and he lives his life and his faith in a way that creates opportunities for connection in every moment,” Rabbi Nancy Kasten says, “and I’m so in awe of his ability to do that.”

One of those opportunities for connection was a four-week series of discussions between him and Dr. Andy Stoker at First United Methodist about the role of Jesus in Islam and Christianity. Stoker remembers they were expecting maybe 40 people, 20 from each congregation, if they were lucky. But 150 showed up that first night and every week after there were more, until they were speaking in front of an audience of 300 when the series concluded. It created connections they couldn’t have predicted, like the 9-year-old Methodist girl who received a hijab from a new friend and asked if she could study the Quran.

“This is what’s going to make Dallas more compassionate, more engaging, and seek the kind of justice we would want for ourselves as we do reach out to our neighbors,” Stoker says.

That reaching out has not come without a price for Suleiman. In early March, just before his series with Stoker started, it was revealed that ISIS had threatened him in one of its videos, calling for followers to “kill the apostate imams” as it showed clips of him with Stoker and some of his other interfaith friends. He found out through a counterterrorism organization in Chicago that studies ISIS propaganda. The FBI later got in touch with him, as well. It wasn’t the first time his name had popped up on an ISIS list—certainly not the first time his faith or his interpretation of it had led to threats—but seeing it on video, he says, was different.

“It’s hard to vocalize,” he says. “I almost resigned myself to this idea that someone was going to harm me.”

His father couldn’t bring it up for weeks. Esraa fretted whenever he left the house. She still does.

“When I finish a protest, demonstration, any activity, any vigil, I call her right away and I can just hear the relief in her voice: We dodged another one,” he says.

But Suleiman is undeterred. ISIS is not going to stop him from spreading his message. It’s not going to stop him from continuing to search for the common ground that unites us. It’s not going to end his friendship with Stoker.

“If I don’t see the guy for a week, I fall apart,” he says, laughing.

On May 4, Suleiman is having a late lunch of shrimp and noodles at a Pei Wei in Richardson. It’s midafternoon on a typical day of what has become a typical week for him. He taught a class at a downtown seminary before meeting me and will head to another one nearby when he leaves.

Tonight, he will speak at a candlelight vigil at Balch Springs’ Virgil T. Irwin Park, not far from where Jordan Edwards, an unarmed 15-year-old, was shot in the head by officer Roy Oliver over the weekend. He was at another service for Edwards last night, with Rev. Dr. Waters and Rabbi Kasten from Faith Forward Dallas, NAACP president Cornell William Brooks, and the activist and journalist Shaun King.

It never stops. Yesterday afternoon, there was a shooting at North Lake College, in Irving, which is next door to his kids’ school. He was “an absolute mess,” he says, as May and Abdullah and their classmates were locked down for a couple of hours, helicopters circling overhead and information scarce as to what exactly was happening. (It turned out to be a stalker who killed a young woman before turning the gun on himself.) When May got home, she had a question for her father: “Baba, do you think Trump sent the shooter?”

“A 7-year-old is having that conversation,” Suleiman says. “She’s connecting the dots. That there are people that hate us enough that they want to kill us. So my 7-year-old making those connections horrifies me. What is she internalizing here? She’s seeing armed protesters at 5 and 6 years old. She’s hearing people call her mom names in public. She knows, and I’m like, This is what our kids are growing up with. They’re going to be messed up if we don’t show them a way, how to respond to this in a productive fashion. They can grow up filled with hatred. She already feels otherized, right? She already feels that way. She’s 7.

“So you think about the community, what Latino kids feel,” he continues. “They’re going to school and some of them are peeing their pants in school—these are middle school kids—because they’re afraid that their parents aren’t going to be home when they get home. The apprehension that black kids feel around cops.”

And so he can’t stop. He’s going to Mali this month to visit with those suffering through famine, and to Jordan at the Syrian border in August, Esraa worrying all the while. He says different clergies have inquired about exporting the Faith Forward model. He knows making those connections, the opportunities for understanding, are more important than ever—for his generation, sure, but for the next one, for May and Abdullah, for Jordan Edwards. In the future, there is hope. But there is a long slog through the present to get there.

That night, as Suleiman stands in a field at Irwin Park in Balch Springs, Kasten and Waters a few feet away, Waters with his hands wrapped around his son Jeremiah’s shoulders, it is the first time I see the moment affect him. There is a hairline crack in his voice, a sheen in his eyes as he begins to speak. But midway through, Suleiman finds his strength and his rhythm.

“This isn’t the first time this has happened,” he says. “It’s not going to be the last. The question is, will it still matter to us when it continues to happen? And will we be just as committed to making sure that no one else has the same fate as Jordan did? You know, a lot of people think that, and I’ve heard this comment, you guys gather too much. You protest too much. You demonstrate too much. You shout too much. You tweet too much. You’re always yelling.”

He’s preaching again, and that murmured call and response from the crowd returns, something even Waters wasn’t able to elicit.

“If you stop killing our kids, we’ll stop yelling.”

Mm-hmm.

“If the people that have been entrusted with authority over us start acting like it, we’ll stop screaming.”

Mmm-hmmm.

“If the videos stop shamelessly showing up on the internet, we’ll stop tweeting.”

Preach.

He tells the hundreds of people that have gathered that we can’t get Jordan back with this, that if we continue to ask God to do his part, then we have to make sure we still do ours, too. “This is on our watch.”

Aaaa-men.

“That’s why we’re here,” he says. “Not just to commemorate, or celebrate the life of Jordan—to show his family that we stand with him. Not just to pray, but to reaffirm that we’re going to do our part, until we don’t have to gather anymore for these types of occasions. I don’t know about you, but I’m sick of it. I’m sick of it. I’m tired.”

Amen.