From the beginning of the meeting, fear filled the room. It was the low-grade sort of fear born of uncertainty, the kind often found in bureaucracies during transitions of power. This happened last summer. The city manager of Dallas, A.C. Gonzalez, had recently announced he would soon retire. He and senior staff were at this City Hall meeting, listening to urban planners and transportation experts tell them about an astounding new study called CityMAP—which is not a map at all, but a Master Assessment Process, a months-long analysis of the greatest transportation and urban design challenges facing Dallas. It is a guide for a new way of thinking about how to plot Dallas’ growth. It called on that staff, which had no idea to whom they would soon report or what that new city manager’s priorities would be, to make bold decisions and chart a course for the city.

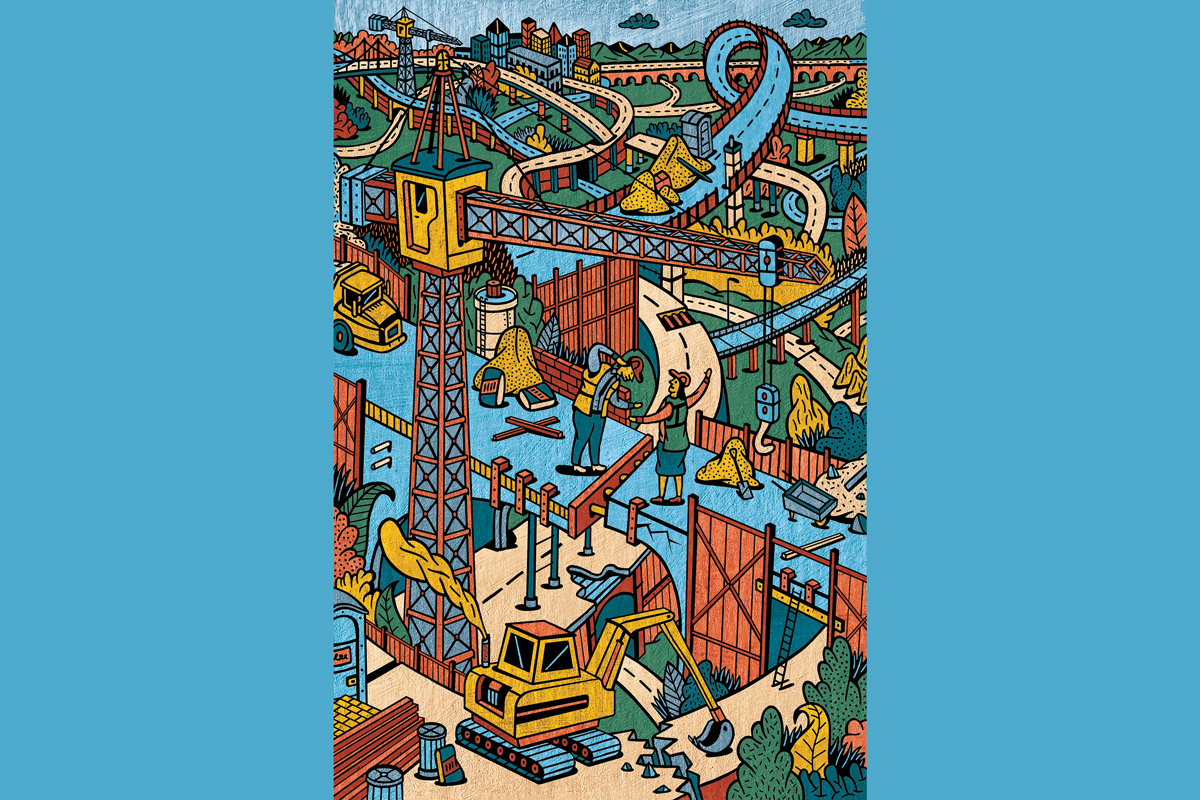

Which is why, as the CityMAP people described the promise inherent in the report—at its core, it’s a vision for unlocking Dallas’ urban potential by redesigning or replacing the highways that choke the city—the presentation, according to one person in the room, “landed with a thud.”

Now that the Council has picked the first outsider in decades as our city manager, we have someone who can grab a copy of CityMAP and use it as a guide for the next two, five, 10, 50 years.

The uncertainty created by Gonzalez’s imminent departure (self-preservation in a bureaucracy dictates that you never support something that your new boss may well want to scuttle) was compounded by simple confusion. It wasn’t because the report is complicated. CityMAP clocks in at 351 pages, but it’s more digestible than many PowerPoint slides you see presented at City Council meetings. The confusion arose because CityMAP isn’t a plan. It doesn’t make recommendations. City staff love plans and recommendations. Recommendations can be ignored, underfunded, superseded by other priorities. Plans can be delayed, derailed, postponed. Staff were looking, as they often do, for the specific action items they could invent ways to do or not do, depending on their new boss’s whims.

CityMAP has none of that. It is something more powerful, a dragon much harder to slay. CityMAP is a story. It is a tale of a great American city that tried to asphyxiate itself with a tangle of highways that acted as a noose, for decades weakening the city’s inner development at the expense of its suburbs. The story is told with the help of data and testimony from an enormous array of city stakeholders, each giving voice to the idea that, despite the pain the highways have caused, their damage is not irreversible. And then it asks the city’s leaders to write the next chapters—the ones that will determine how this story unfolds.

Since that meeting, predictably, CityMAP has sat on a shelf, gathering dust. But this story can have a hero, one with a name that sounds like a TV action star: T.C. Broadnax. Now that the Council has picked the first outsider in decades as our city manager, we have someone who can grab a copy of CityMAP and use it as a guide for the next two, five, 10, 50 years. And that fearful staff can get to work.

“This is the moment for the new city manager,” says Scott Polikov, president of urban design group Gateway Planning and one of CityMAP’s many contributors. Polikov, who has helped design or fund forward-thinking city projects with more than 50 cities, says the transportation decisions outlined by CityMAP affect each city function. “Housing, job creation, economic development, policing. CityMAP gives the city manager the ability to work with a very diverse Council and mayor and say, ‘We can’t make ad hoc decisions going forward and still do it effectively with limited resources. We have to prioritize catalytic outcomes that then lead to a reversal of our tax-based challenges.’ This document sets forth the major transportation infrastructure issues, as they relate to quality of life and neighborhood design, for the city manager to empower the entire city of Dallas. Fearing it is the wrong view. It is a governance platform for informed decision-making. They just have to see that.”

The short version of CityMAP’s genesis has its own hero. Halfway through his six-year term as a Texas Transportation Commission member, North Texas representative Victor Vandergriff decided the Texas Department of Transportation needed to change the way it does business. Instead of trying to solve every traffic problem by building more and wider roads, TxDOT needed to differentiate needs by type and place. Fixing congestion and spurring growth in urban centers like Dallas, he suspected, required undoing decisions made decades ago to build a city better suited to cars than people.

Vandergriff convinced TxDOT to talk to experts and consultants all over North Texas, synthesizing their concerns, research, and prescriptions for change into the final report. CityMAP focuses on choke-point areas like I-345, the removal of which would spark tremendous economic and cultural development, and I-30 near Fair Park, which should be lowered or moved. It discusses economic development and job creation, as well as the need to make streets more walkable and bikeable.

CityMAP needs to be on T.C. Broadnax’s desk from Day One. It needs to be his guiding document, his sacred text. The progressive members of the Council, the mayor, and other leaders have given it their thumbs-up.

“CityMAP was and is an extraordinary document,” says Patrick Kennedy, newly appointed DART board member and urban designer. (Disclosure: Kennedy co-founded, with D Magazine owner Wick Allison, the Coalition for a New Dallas, a super PAC that advocates for smart urban planning.) Kennedy says that no other state department of transportation had, before CityMAP, looked at inner-city highways holistically, with the open-eyed awareness that these structures have huge effects on land value and quality of life outside their rights-of-way. Other cities in and out of Texas have since asked for a similar report from their states, ones that begin the discussion about how better to make cities work for people rather than cars. This approach has been applauded by the Obama Administration; past U.S. Department of Transportation secretary Anthony Foxx often said that making transportation decisions with public input up front, rather than taking ideas to the public for yes-no votes, should be the model for all transportation projects, with a focus on reconnecting rather than segregating and isolating.

Realize: we did just that with CityMAP. And we did it first. In Dallas, for heaven’s sake. That’s why Kennedy says CityMAP is remarkable. It represents a 180-degree turn from the usual way of doing big projects.

What may be even more remarkable, though, is that this huge state bureaucracy, TxDOT, is inviting Dallas to a conversation. It is asking for feedback on this document so that the agency can prioritize the urban changes to our city in a way that aligns with our unique history, desires, and vision.

“TxDOT is willing to be at the table on those terms,” Polikov says. “It says so right in the document. ‘Sit down with us, and let’s rewrite how we make decisions. We are giving you this offer.’ That’s an amazing opportunity.”

It’s an opportunity that is right now being squandered. We should be having this public discussion about CityMAP, devising our list of to-dos that come from reading it. But we’re not, and that must change.

CityMAP needs to be on T.C. Broadnax’s desk from Day One. It needs to be his guiding document, his sacred text. The progressive members of the Council, the mayor, and other leaders have given it their thumbs-up. But we need the staff who make the city run, who dole out the dollars, to embrace it.

“We need a legal entity whose mission statement is to carry it forward,” Kennedy says, “to choose options in the best interest of the long-term health, growth, and revitalization of the core and the southern sector. I believe we need a redevelopment authority composed of a handful of public and private stakeholders that will determine the phasing strategies and select the options, and ideally accelerate the redevelopment of downtown so jobs and amenities are not so far away. We need that so Fortune 500 companies don’t relocate ever closer to the Red River, so that schools, and parks, and mixed-income, mixed-use housing developments can repopulate the core. Without that entity, there is a likelihood we have created an extraordinary process with ordinary results. Back to the 20th century.”

Broadnax was hired as a change agent. He has time to rescue CityMAP and change the city for the better. That’s how this next chapter should begin.