For anyone who has listened to Krys Boyd in the decade that she has hosted Think on KERA 90.1—a cerebral, sober interview show, the quintessence of public radio—it’s difficult to decide which fact from Boyd’s biography comes as the bigger surprise: that she was a prom queen or that she met her first husband in an El Paso lesbian bar while on a date with his best friend. In truth, the lesbian bar wasn’t a lesbian bar by that point. Straight folks had discovered it and ruined the joint. But still.

These aren’t the sort of details about herself that Boyd offers up easily. They certainly don’t crop up in the course of her show. That’s one of the things that makes her such a great interviewer. She possesses a limitless curiosity and a near pathological drive to prepare, yes. And there’s the voice. It is effervescent, smiling, maybe even erotic at times, in the way she over-enunciates to fight a slight lisp that betrays her when she’s tired. But beyond all that, she has a gift for sublimating her ego, becoming an intensely active listener, all attention on the guest.

James Fallows has felt that focus. On January 2, Think began an ambitious expansion, broadcasting on stations all across the state (it now reaches 70 percent of the public radio listeners in Texas). Fallows, a writer for The Atlantic who’d been on the show before, was the first statewide guest, piped in from a studio in Washington, D.C., to talk about a four-year reporting project he’d undertaken with his wife, traveling through and living in smaller American cities to better understand “Life in Trump’s America,” as that installment of Think was titled. Boyd sat alone in a studio at KERA, just north of downtown. Large headphones held back her brown, shoulder-length hair. When she looked at her production staff in an adjacent control room, it was through a soundproof window and a pair of Warby Parkers.

Twenty minutes into the interview, listeners in Waco, Austin, San Antonio, and Houston got treated to two Krys Boyd signature moves. The first: she asked a question of such perspicacity that the guest was forced to reevaluate his entire worldview, like Neo when he’s first shown the Matrix. Fallows is an Oxford-educated intellectual who has written 10 books and been interviewed more times than he could count. Many Think guests are similarly experienced authors, sometimes in the middle of exhausting promotional tours. Even so, it’s not uncommon for them to preface an answer with “That’s a good question.” It can be a sincere compliment or a stalling technique or both. Fallows fielded a question of another order. Space prevents a transcription of the exchange and a detailing of the necessary context, but Fallows had to admit that he’d never even thought of the subject under consideration from Boyd’s perspective. After going into what he called a “real-time” reaction to the query, Fallows promised to think some more about it.

Then came the second signature move. In response to something Fallows had said, Boyd offered a short, sweet hmh. There are online message boards where Krys Boyd fans meet to trade hmh audio files that they’ve clipped from her show, comparing their favorites and writing disquisitions on the nuanced meaning of each—or there should be such message boards. It is the briefest of utterances, but she serves dozens of flavors of it, ranging from a hmh that means “Yes, go on” to one that’s best interpreted as “That surprises me, even though I’ve read your entire book and had an assistant dig up background research for me.” There is even a rare Boyd hmh, only detectable to longtime listeners, that means “I deeply disagree with what you just said, but this is public radio, so I don’t want to sound judge-y.”

After the show ended that day, after Boyd’s co-workers and bosses piled into the studio to celebrate the milestone, Fallows, via email, offered his own assessment of her work: “One of the bright spots for American journalism and discourse, amid all the well-known reasons for despair, is the nationwide chain of excellent public radio talk-show hosts and interviewers. As my wife and I have traveled around the country we’ve been able to listen to a lot of them, and through the work of our magazine, over the years I’ve been on many of their shows. I think that Krys Boyd is among the very best in the entire country, in the way she thinks about interviews and the results she is able to get from guests.”

To which Boyd herself might respond: hmh.

Interviewing the interviewer turns out to be a challenge. Tucked into a back booth at the Stoneleigh P on a Friday afternoon after she has gotten off the air, Boyd orders a bowl of lentil soup and an iced tea. She more than once says, “I hesitate to tell you this,” before revealing something that is totally innocuous and requires zero hesitation.

And here I’ll go ahead and mention something that Boyd would never bring up if she were writing this story. I am sitting on the other side of that booth, drinking beer. Furthermore, I have been a guest on Think three times that I can recall, which I feel makes us something approaching friends, even though I have never seen Boyd in a social setting. Well, except the time I came home one evening and found her sitting at my kitchen table with a group of women, one of whom was my wife. They are certainly friends. Not close friends. There you have it.

The foregoing I offer not only because it’s my journalistic duty but because Boyd knows me well enough that her reticence to share personal details and my teasing about that reticence leads her to tell me her favorite parable. She doesn’t use such formal language, but she comes close, and since it’s Aesop, here’s the original:

The Wind and the Sun were disputing which was stronger. Suddenly they saw a traveler coming down the road, and the Sun said, “I see a way to decide our dispute. Whichever of us can cause that traveler to take off his cloak shall be regarded as the stronger. You begin.”

So the Sun retired behind a cloud, and the Wind began to blow as hard as he could upon the traveler. But the harder he blew the more closely did the traveler wrap his cloak round him, till at last the Wind had to give up in despair.

Then the Sun came out and shone in all his glory upon the traveler, who soon found it too hot to walk with his cloak on.

To which the Wind says: hmh.

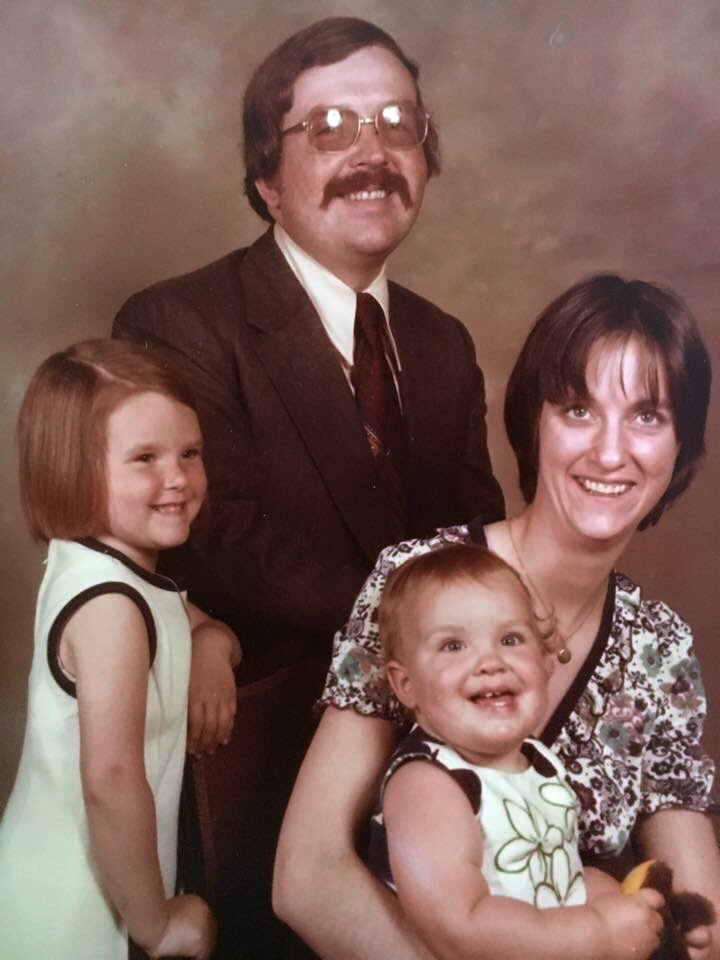

Krys Boyd spent her early childhood on Long Island, the eldest of three sisters born into a family Catholic enough that her mother had 14 siblings (one adopted) and lived for a time in a convent before marrying her father. Her dad worked in freight sales for American Airlines. A promotion moved the family to El Paso in 1984, when Boyd was 13.

It sounds like the outline for a horrible beginning to high school, getting uprooted from the East Coast to live in a West Texas town and attend an all-girls school where she was in the white minority. But Boyd loved it. On Long Island, she half froze to death twirling her baton in the St. Patrick’s Day parade, but mid-March in El Paso brought weather so warm that she and her sisters could swim. It felt exotic. Boyd loved the deep blue skies and wide-open spaces, including her new house, which had three bathrooms, 200 percent more than they’d enjoyed on Long Island.

Even the nuns at Loretto Academy made the transition easy. They were gentle and funny. The biggest challenge for her in school might have been adjusting to the rampant hugging. Boyd couldn’t figure out why her Latina classmates felt compelled to embrace between classes. Where she came from, that kind of contact was reserved for birthdays. Despite her aversion to hugging, though, she was voted prom queen. Her date was a platonic friend she’d met while doing community theater—not to be confused with the dinner theater she did with a troupe from the University of Texas at El Paso. Her parents worried about the bad influence all these older thespians might have on their little girl; they needn’t have.

Boyd went to TCU because the school offered her a partial academic scholarship and her father thought, as she recalls, “This seems like a nice school for our good girl.” Her decent grades there belied her taste for criminal trespass and scatological humor. The venue for the former was provided by T. Cullen Davis, once the richest man to stand trial for murder. By then he’d had to abandon his Fort Worth mansion. “It was a place that college kids with a couple beers in them liked to break into with flashlights and wander about,” Boyd says. She claims this adventure did not constitute breaking and entering because her group of reprobates didn’t actually break anything to get into the house. But she is wrong.

Dad might have also taken a dim view of his daughter’s involvement with Lights Out, a student-produced TV show that aired ever so briefly on KTVT Channel 11, then an independent station. Imagine Late Night With David Letterman, only replace Letterman with a kid named Michael Austin. (The show actually started out as TCU Late Night With Michael Numberman, but Austin and crew were forced to change the name to avoid legal trouble.) Guests included the TCU Horned Frog mascot and George W. Bush. Boyd was the head writer for Lights Out, the one girl working in a room full of boys, all of whom called her Boyd and trafficked in jokes based on sexual innuendo and bodily functions. She liked it. The experience was certainly unlike any she’d had with the girls at Loretto. To this day, Boyd has a weakness for double-entendres.

More important, in her two years of writing for the show, she learned how to fight for her ideas. “I look at it now, and I can’t believe that show was so important to us,” she says. “The product was inferior, but the experience was grand.” Boyd fans will be delighted to know that LightsOutShow.com is a thing that still exists and that it and the videos it displays are as inferior as could possibly be hoped for. The only letdown: Boyd herself never appears on camera.

She graduated with a radio-television-film degree but, she admits, no idea how to pluck her eyebrows. Either that facial hair or 1992’s lousy job market kept Boyd from finding work. “I moved home, like shoulders down, ‘I guess I’ll look for a job at Chili’s,’ ” she says. But she landed at KDBC, El Paso’s fourth-ranked television station. For $5.50 an hour, she covered traffic accidents and eventually did some fill-in work behind the weekend anchor desk.

“We always thought of her as the smartest person in the room,” says Jason Wheeler, who is now an anchor in Dallas at WFAA Channel 8. His first TV job, though, was at that lowly station in El Paso with Boyd. They were part of a crew that their boss called The 25 Club, because they were all so young and hung out together, working and hitting the bars in Juárez with equal intensity. “She always used these 50-cent words. We were in a meeting one time with a consultant. Everybody wants to impress the consultant, especially when they are in their first job. I remember she raised her hand to bring up some point, and she said, ‘I don’t mean to be a sycophant—’ Everyone in the room just sort of looked around, like what the hell does that mean? What’s a sycophant?”

Wheeler is one of several people who know Boyd well and say, unprompted, that under different circumstances she might have become a stand-up. They point to her quick wit and sense of timing. And the way she studies people. “If you spend an hour with her, there’s a good chance that she has an impression of you down already,” he says. “I guarantee you she has impressions of every person she works with.”

She sounds like someone who might do well on a personality-driven morning-drive radio show, which Boyd did while also attending to her television duties in the evening. Oddly, though, she played the straight woman on 92.3 The Fox, an oldies station. The two guys on the show called her Boyd and did their best, between her newscasts, to tease her and throw her off balance. They rarely succeeded. “She has a pure heart,” says Dave Crome, who did sports on the show. “It endeared her to the audience, and people connected with her. They’d call in. ‘Stop giving Krys such a hard time!’ ”

It was around this time that Boyd met José Villaseñor, who did PR for the Greater El Paso Chamber of Commerce. She was dating Villaseñor’s best friend, a young man whose name the reader need not trouble her mind with, in Boyd’s opinion. These things happened so long ago. But her first encounter with Villaseñor came at Bombardiers, the aforementioned erstwhile lesbian bar. That much can be committed to the record.

For a while, seven months or so of double-dating, nothing happened. But then the foursome took a trip to Ruidoso, New Mexico, where Villaseñor’s family had a ski cabin—or the foursome was supposed to travel together, until Villaseñor’s girlfriend’s conservative parents derailed their daughter’s plans, leaving Boyd alone with the two men in what can only be portrayed as a twist of fate. Boyd’s boyfriend, in her words, was a fuddy-duddy and turned in early one evening. His last mistake. She stayed up instead with Villaseñor, conversing late into the night. The guy wasn’t conventionally handsome, but the more he talked—he spoke beautiful Spanish and unaccented English—the more attractive he became. She fell in love with his mind.

By 1999, Boyd had had her fill of television news, camping outside churches with a cameraman, waiting to interview grieving families. The middle Boyd girl, Laura, had a good job at a strange-sounding outfit called Broadcast.com, and she convinced her elder sister to move to Dallas to become a producer there. This was just as Mark Cuban was selling his company to Yahoo for all the money in the world.

“You have successfully installed the Yahoo player. Thank you for choosing Yahoo.” That’s what the disembodied Boyd, twirling her baton, told new users. Along with nearly everything else about the job, the voice-over work depressed her.

Two years in, she jumped ship to work at KERA and host a talk show, Conversations With Krys Villaseñor, that aired every weeknight at 7 pm until it didn’t. Less than a year after the show debuted, KERA laid off a quarter of its entire staff, including Boyd. Then things went from bad to much worse.

“I had a premonition,” Boyd says. “Always. From the moment we got together. I always—I knew. José traveled a lot for work. He was in PR. I thought it would be a plane crash. I had this thing where I couldn’t just say, ‘I’ll see you Tuesday when you’re back in town.’ I would make him say it back to me: ‘Yes, I’ll see you Tuesday.’ I had a weird sense.”

She found her husband at home. His heart had failed him at 31, leaving Boyd with two kids, 10-month-old Clara and 3-year-old Ben. There was no life insurance, and the money from her stint at Yahoo had been pissed away by a reckless investment adviser. Not knowing how she would make the next mortgage payment on her ranch-style house in Lakewood, Boyd got a job offer from the television side of KERA. The station had secured funding for a documentary about the JFK assassination and how it changed the news business. She signed on as a producer despite being underqualified.

“I think they thought, Krys really needs the money,” she says. “They expected me to do some work, but I think they thought, If she comes in every day and folds under her desk, then we can make this work. We have enough experienced people on the team who’ve done long-form documentary.”

She didn’t fold. To the contrary, the work gave her a refuge. For eight hours a day, the events of 1963 commanded her full attention. On her lunch break, she’d walk the Katy Trail and listen to her coworker Glenn Mitchell’s talk show on a little Mickey Mouse radio receiver that she borrowed from her son Ben. In that terrible year, Boyd learned to be a single mother, and finishing the documentary, too, gave her a newfound confidence.

“At the end of it, I was a different person,” she says. “I lived for a long time with the illusion that I had a lot of control over everything, and I still want to believe that. I like the idea. But I know that it’s not true.”

Two years later, on a Friday morning in November of 2005, Mitchell came to work not feeling good. His producer, Jeff Whittington, thought he had the flu and sent him home before he could go on the air. That Sunday, as Whittington was hauling some new Ikea cabinets into his kitchen, Mitchell’s wife called to say that he’d had a heart attack and died in his sleep. He was 55 years old.

It took the brass at KERA about a year to find Glenn Mitchell’s replacement—or, rather, his successor, because anyone who spent time in his orbit would agree that Mitchell couldn’t be replaced. Boyd was still working on the television side of KERA and had been filling in almost daily on what they were calling, for the interim, The Talk Show. A younger Boyd would have let that work speak for itself, rather than take the emotional risk of putting herself out there for the job and getting shot down. Not this time. “I wanted that job so bad,” she says. “With this job, I was elbows out.”

The show might have been called 30 Questions. That’s how many Boyd typically prepares for each interview, and that was one of her suggested titles that thankfully didn’t make it past the whiteboard. Whittington came up with Think.

The weekend before the show debuted, Boyd took a swim through Match.com, figuring that once she officially became the host of a show on KERA, she couldn’t very well go looking for dates online because it would reflect poorly on the station. Boyd was drawn to a man named Matt DeMoss. He had two children, Heather and Harrison, from a previous marriage and was an editor at Bibliotheca Sacra, a journal published by the Dallas Theological Seminary, where he’d earned a master’s degree. In his

Match.com profile, DeMoss wrote that he found Sarah Vowell sexier than Pamela Anderson. That’s what did it.

For the next three weeks, DeMoss had an interesting relationship with his radio. He was already an avid KERA listener, but now when he tuned in, he heard the voice of a woman who was sending him emails every day, and who confessed that she had a crush on Bob Schieffer. On their first date, at a coffee shop on Lowest Greenville, he gave her a framed picture of Schieffer for her desk at work. It was another good move. He got a dinner date with her the very next night. They were horrible customers at Cafe Izmir, occupying a table for four hours. For DeMoss, it felt like 20 minutes.

A year and a half later, they eloped to the Dallas Arboretum, sneaking off to a corner of the garden to get married. Sujata Dand, a friend of Boyd’s from the station, served as witness, maid of honor, and photographer. The bride and groom wrote their own vows. In Dand’s estimation, Boyd’s were “fine.” But DeMoss’ were “a-maze-ing.” “Oh, there’s nothing more that you want for your friend than to know she is marrying someone who loves her times a million,” Dand says. “At that moment, I remember feeling: this is the best thing she could have ever done.”

Today they live in a 103-year-old house in Munger Place filled with their four teenagers and a Chihuahua-Boston terrier mix named Birdie. In the early days of Think, Boyd probably spent 10 hours preparing for the two guests that fill a typical show. After doing some 4,000 interviews, that prep time might have shortened a little, but DeMoss says she hasn’t let up much. On those rare occasions that he beats her home, he doesn’t get much love when she shows up. “It’s amazing,” he says. “She will walk through the front door, drop her keys, set down her purse, walk straight to her green chair in back, sit down, open the book. Elapsed time is like 12 seconds. She clocks in the hours.”

Boyd says she doesn’t know how many people listen to her show, and she’s almost certainly not lying. Her humble assessment of the statewide expansion: “It took me 10 years to get to Waco.” But that’s just the beginning. When Diane Rehm retired at the end of last year, her D.C.-based show was broadcast on nearly 200 stations across the country. Rick Holter, the vice president of news at KERA, harbors no delusions of landing Think on each slot once occupied by The Diane Rehm Show. But he does call the Texas move a “soft launch” and says they are looking at making a national push later this year.

“It’s happening at a time when I have a lot of confidence in my ability,” Boyd says. “I feel very comfortable in my skin now in a way I didn’t years ago.”

And again the Wind says: hmh.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author