My father was a major player in Dallas real estate back in the days when being a major player in Dallas real estate entailed a necessary degree of criminal liability. He was eventually indicted by the feds in connection to some sort of land-flipping case that he’s explained to me several times but that I’ve never quite managed to grasp. Presumably the FBI couldn’t understand it, either, since my dad took the case to trial, where the judge dismissed it with prejudice before it even went to a jury. His partner, the late Lou Reese, pled guilty and served a short prison bid. Yet whereas Reese managed to keep a large chunk of his assets, my dad stayed out of prison but went broke in the process.

To feel self-actualized, my dad has to have large amounts of money so that he can go on expensive African safaris and kill large animals, something he did throughout his ’80s stint as a millionaire. “I’m a killer,” he would tell me in the car when I was a kid. “Don’t hunt what you can’t kill,” he would also tell me, quoting the tag line from the 1993 Jean-Claude Van Damme film Hard Target, which involves millionaire adventurers who hunt men for sport and which he took me to see several times. He also bought me the poster.

Finally, in 1998, my father got a chance to make huge amounts of money in a place that would put him near the wild game he craved: the East African nation of Tanzania, where the “Big Five”—African buffalo, lion, elephant, leopard, and rhinoceros—roamed the plains of the Serengeti. He had been recruited by Steve Christenson, an old Dallas business associate and fellow Dallas Safari Club mainstay, to go to Tanzania in order to harvest mahogany from a land concession that they were supposed to get from the government with the help of Ademba Gomba, an animist lawyer with the state-run shipping company.

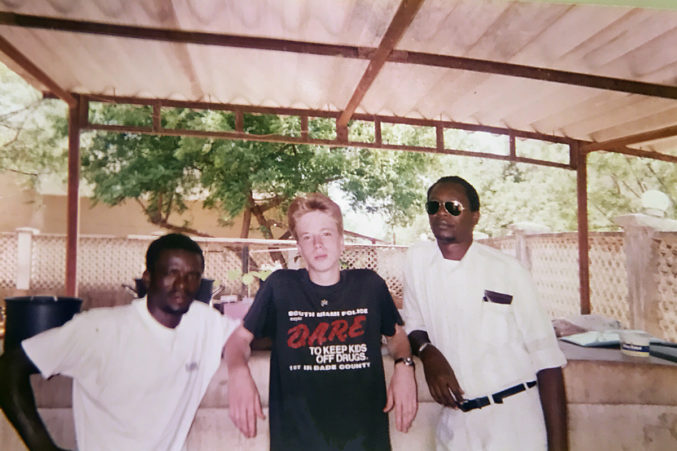

The team would also include my mother’s brother Kim—a Vietnam veteran, geologist, Clapton fan, and ex-millionaire who’d lost all of his money in large part due to an addiction to alcohol. Also, we’d have several random ex-military men with us, among them a former member of the Irish Naval Service and a Desert Storm sniper who was then working as a bartender at the now-defunct Tipperary Inn on Live Oak. There was, in addition, a fellow named Grant who looked like Mr. Clean and seemed to be Steve’s cocaine dealer but had no designated role in the operation that I could divine. Oh, I was coming along, too, largely because I was capable of learning basic Swahili from a textbook on short notice and was not welcome to return to The Episcopal School of Dallas.

We arrived in Tanzania’s de facto capital at the time, Dar es Salaam, a bizarre city of uncounted millions—the government had never managed to take a census. It turned out that the house we’d gotten only had three rooms, so most of us would be living in tents in the yard. Also, the U.S. Embassy had been blown up by Al Qaeda a few weeks prior, so I’d have to go take my tests for my Texas Tech high school correspondence course at the new, extra-secure embassy, which required that I walk up a hill while an American soldier pointed a mounted machine gun at me.

At first, our crew was generally content to relax and leave things in Steve’s hands. Mostly we smoked cheap marijuana and went drinking. Within five minutes of arriving at one of the nightclubs we frequented, a lady came up to me and grabbed my crotch.

“Do you think some of these women are prostitutes?” I asked the other guys, who laughed. Later that night, Grant bodily tossed one of the hookers out of the club for reasons that probably made perfect sense to him.

Soon there were signs that Steve’s ambitious plans to leverage our lumber project into a vast neo-imperialist economic empire might be less of a sure thing than originally envisioned. Somewhere around $50,000 of our funds had been eaten up during an advance trip by Steve’s secretary, with whom he’d been carrying on an affair in Dallas and with whom he was now carrying on an affair in a tent. Despite having partnered with a reasonably connected government official, we’d been unable to get our equipment out of customs.

Things deteriorated rather quickly over the coming months. My dad spent more and more time buying and setting off what he said were fireworks but which were clearly dynamite, and Uncle Kim, stoned and paranoid, would come out and yell at him because he thought the FBI counter-terrorism people who were all over the city would descend on our hobo camp and find his weed. We got some actual bottle rockets and fired them at people on nearby rooftops. My dad and a few others came down with mysterious respiratory diseases and suffered outbreaks of malaria, necessitating taxi rides to the sort of hospitals you’re allowed to smoke in.

Our Desert Storm vet claimed to me one night that his sniper rifle, impounded by customs, had been calling out to him, and concluded from this that he should go swim in the ocean. I objected that we’d been drinking pretty heavily and smoking cheap marijuana and that he’d also taken a couple of Valiums from the medical kit, but he assured me that he and the ocean had “an understanding.” The vet was apparently telling the truth, because he was there the next morning, kicking a prostitute out of the house without paying.

Several months having passed with no visible progress on the actual cutting down of upscale trees, Uncle Kim staged a sort of mutiny against Steve, which broke down when the others lost their nerve at the last minute. It was at this point that it became clear that Grant was employed as Steve’s enforcer.

Shortly afterward, Ademba came by and said he needed our passports for something to do with officialdom. Two weeks later, we were unable to get any information as to why they had yet to be returned. Finally, Kim called a family member with ties to the Department of State, which made a more or less official inquiry to the Tanzanian government. That day, a visibly haunted Ademba rushed over to the house with the passports and explained that no harm was intended. Steve was notably silent on the issue, and in fact on all issues. He now spent most of his time in his tent, drinking.

My mom bought me a ticket home; the others managed to get back to the States over the next few months, with the exception of one veteran from Alaska who agreed to work on some white Rhodesian fellow’s river rafting tour in exchange for beer. The sniper got his bartending job at Tipperary back. Steve Christenson died in 2015, which will save him the trouble of trying to sue me. My dad, who is now in the oil business, continues to enjoy films involving men who hunt other men for sport.

Write to [email protected].