Cops in Dallas have it tough on the best of days. They put their lives on the line to keep the city safe, many of them facing danger for what seems inequitable pay. Dallas police salaries start at about $44,000 a year, which is $6,000 less than rookie Dallas ISD teachers earn and nearly $20,000 less than a starting officer in Plano. It’s a stressful job for a lot of reasons. In the wake of the July 7 shootings that left five Dallas officers dead (one was a DART cop), police Chief David Brown spelled it out.

“Every societal failure, we put it on the cops to solve,” Brown said. “Not enough mental health funding. Let the cop handle it. Not enough drug addiction funding. Let’s give it to the cops. Here in Dallas we have a loose dog problem. Let’s have the cops chase loose dogs. Schools fail. Give it to the cops. That’s too much to ask. Policing was never meant to solve all those problems.”

It isn’t just middle-class homeowners who need relief. Renters, too, are about to be hit if the higher property valuations aren’t dealt with. The taxes from those increases are passed on to the 48 percent of Dallasites who rent.

Brown was saying that we must look beyond this one incident and ask ourselves if our priorities are in line with our budget. For years, the police unions have argued that Dallas needs more money to recruit good cops, put more cops on the street, and pay officers enough that they can afford to live in the city they serve.

Enter Judge Clay Jenkins, the chief executive of Dallas County, whom many considered a hero for how he handled the Ebola crisis. Jenkins has come up with an idea regarding property taxes that he hopes city and school taxing entities will adopt, an idea that would surely affect how we pay for cops and other vital city services. In recent weeks, he’s been going around to officials in cities all over Dallas County pitching his idea. He wants to increase our taxes to increase salaries and beef up other services, right?

No. In fact, Clay Jenkins, a Democrat, wants to reduce our property taxes. With memorial services still fresh in our memories and the chief of police calling for more support of the services that make cops’ jobs easier, Jenkins wants to take money out of the budget.

You know what? He’s right. Too much of the local tax burden falls on the middle class, and not enough is shouldered by wealthy people and owners of commercial properties.

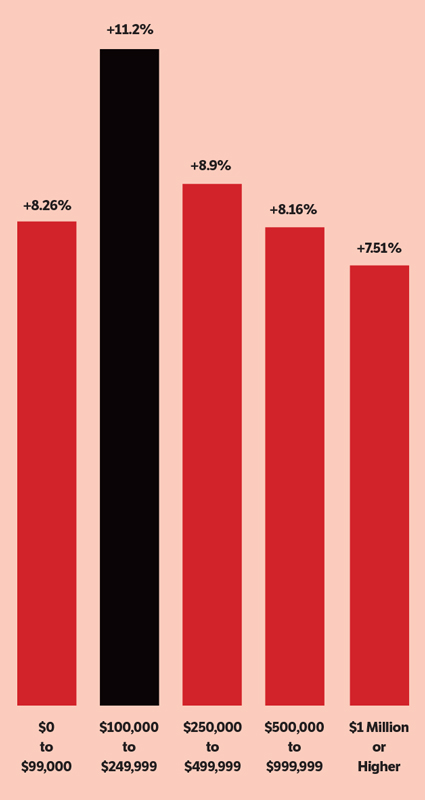

Jenkins’ plan is a response to the recent increase in property valuations as determined by the Dallas Central Appraisal District. Home valuations, overall, went up 11.2 percent this year (that number will fall a bit as protests are worked out). The county budgeted for only a 7.5 percent increase. So that’s where Jenkins wants to cap it.

“The middle class didn’t get a 10 percent pay increase,” Jenkins says, “so they shouldn’t get a 10 percent property tax increase.”

But what about the cops? And rounding up feral dogs? And fixing the terrible streets? How do you reconcile the need for more money for public safety and the very real fear that rising taxes are pricing the middle class out of Dallas? It’s a complicated question, and there is not a one-size-fits-all answer. But there are a few steps we can take right now, and they all involve the wealthy and the businesspeople of Dallas.

In Jenkins’ mind, a property tax reduction isn’t an either-or proposition. You can fund cops and schools and hospitals without breaking the backs of the middle class—a real concern, given that Texas has the fifth-highest property tax burden in the nation. Jenkins says people are being priced out of their homes, since wages aren’t rising nearly as fast as home valuations. In Dallas County, middle-class wages have gone up just over 4 percent the past five years. Meanwhile, property taxes increased 45 percent from 2005 to 2014. Jenkins wants all the taxing entities to cap their increase in collected taxes closer to the amount they’d already budgeted for a property tax increase (the 7.5 percent).

It isn’t just middle-class homeowners who need relief. Renters, too, are about to be hit if the higher property valuations aren’t dealt with. The taxes from those increases are passed on to the 48 percent of Dallasites who rent. The average rent in Dallas went from $986 in 2015 to $1,101 this year, up nearly 12 percent.

Jenkins’ idea to cap taxes crystallized after he saw an excellent Dallas Morning News analysis that showed the wealthy—in terms of the houses they live in and the commercial properties they own—were getting a better deal than everyone else. In the city of Dallas, the paper noted, “the majority of homeowners with properties worth $100,000 to $250,000 saw appraised values rise 12 percent or more this year … [while those] worth more than $1 million saw an increase of 6.7 percent or less.” And while about 70 percent of Dallas homeowners saw their property taxes go up, only 30 percent of commercial properties did. That’s absurd.

“Too often, people in local government have to tell people what they can’t do for them,” Jenkins says. “We say, ‘Well, I’d like to get that done, but I just can’t.’ But we can control this. This is something we actually can do for the people who need help.”

He says the smaller increase doesn’t mean that cops will be shorted. Their salaries aren’t paid with county funds, and the Commissioners Court is already working to do things on the county level to help the sheriff’s department get body armor, better Tasers, more rifles, and easier access to counseling services. Jenkins says his proposed cap on a tax increase would meet the budget the county prepared this spring and still give all county employees a 5 percent raise.

of a median middle-class home in Dallas County increased

by 11.2 percent from 2015 to 2016 , significantly more than

in any other price range and much higher than the county’s budget

projection. For most middle-class homeowners in the

city of Dallas, it was even higher—12 percent or more.

Source: Dallas Central Appraisal District

As Jenkins makes the rounds, pitching his idea, some politicians in Dallas County cities have already voiced support, saying they’ll find a way to balance needs with fair taxation. For some, this would be very difficult. Dallas, for example, is already facing a $19 million budget deficit, smaller than in some past recent years but nothing to scoff at, especially when you’re already in the spotlight to do right by your police force.

There is a way, though, for Jenkins to get what he wants and not short ourselves the funds we need. And it’s a permanent fix to the system. Forget the tax rates. We should address the process by which the property valuations are arrived at. We should make the price of real estate sales public.

Texas is one of the few states in the country where you can’t easily discover the truest indicator of a property’s real market value, the price for which it most recently sold. Making those transactions public would help reduce the number of people—we all know them; you may be one of them—who successfully fight to have their home value reduced to $2 million when they paid $2.5 million five years ago and know they could get $3 million today on the open market. And Jenkins notes that the inability to properly affix a true market value to commercial property is where we really miss out on needed funds.

The arguments against making sales prices public are weak, especially since the most sensible one—that doing so would make the state want to levy a tax on real estate deals, as some states do—was banned by Texas voters in last year’s election. And taxing entities want the best information possible so they can make property taxes more equitable, which is why the city of Austin recently sued the state to force it to make sales prices public.

Ultimately, tax relief is always welcome. But you can’t argue to pay less and then say that your city should spend more on cops because you back the blue. And you certainly can’t do that if you’re already contributing too little.