For two little boys, the events of that evening would shape their futures. The sons of the murder victim and the man convicted of the crime—one black, one white—have suffered every day of their lives with two strains of the same sorrow. Their shared story is not just about the pain of losing a parent. It’s about injustice.

•••

The Tommy Lee Walker case came to my attention several years ago, when I began looking for an execution in Texas that could possibly be proved wrongful using DNA. My search focused on Dallas County, because DNA evidence taken during criminal investigations here was often refrigerated and saved for decades, a policy of the Southwest Institute of Forensic Sciences and one of the reasons Dallas County has more exonerations than almost every other county in the nation.

One of the first people I talked to about the case was L.A. Bedford, Dallas County’s first black judge, a respected attorney who worked for decades in South Dallas. When I mentioned Walker’s name to him, Bedford exploded, saying it was the “greatest injustice I have ever seen in my life.” Bedford died in 2014, but before he did, we talked one last time about the Walker case. I was feeling disheartened about the story and asked him whether he thought I should keep working on it. Bedford said, “Only if you care about the truth.”

•••

In 1953, Dallas was booming. the U.S. census three years earlier had pegged the city’s population at 435,000; a decade later, it would be 680,000. But in many ways it was still a small Southern town. The Dallas Morning News ran a front-page item about a calf turning up in a ladies bathroom at a service station and another about a woman who was doing yard work when she discovered a snake in her dress. The most popular radio program at the time was a Sunday morning variety show called The Early Birds. Broadcast by WFAA-AM in front of a live audience, it featured a character named Little Willie, played by a performer named Ben McClesky wearing blackface. Dallas had not yet been altered by the Kennedy assassination or the civil rights movement. Just two years earlier, in fact, there had a been a series of bombings in South Dallas, as whites terrorized black people moving into their neighborhood. A grand jury handed down nearly a dozen indictments, but no one brought to trial was ever convicted.

Over the summer, reports surfaced of a “Negro Prowler.” In one neighborhood after another, white women called police with tales of a naked black man peeping into their homes, exposing himself. Police always arrived after the perpetrator had fled. His crimes left no evidence, just the stories of terrified women splashed across front pages. Henry Wade urged vigilance and patience.

Then, on the night of September 30, 1953, a horrific discovery on Lemmon Avenue set the city’s fears on fire.

Just after 9 o’clock, an airline reservations clerk was driving home from work at Love Field when his headlights illuminated a small, struggling figure in the middle of the road. It was 31-year-old Venice Parker, crawling on her hands and knees, her dress torn and drenched in blood, her throat slashed. The driver pulled over and ran to her side, asking, “Lady, what’s happened?” He would testify later that Venice was able to say only, “I was stabbed,” before falling silent. He half-walked, half-carried her to the car and sped back to the airport, where he knew he’d find police. He said he did not hear Venice speak again, that she issued only what he described as “gurgling sounds.” He testified that during the short drive, her feet kicked at one of the back windows when she seemed to go into convulsions.

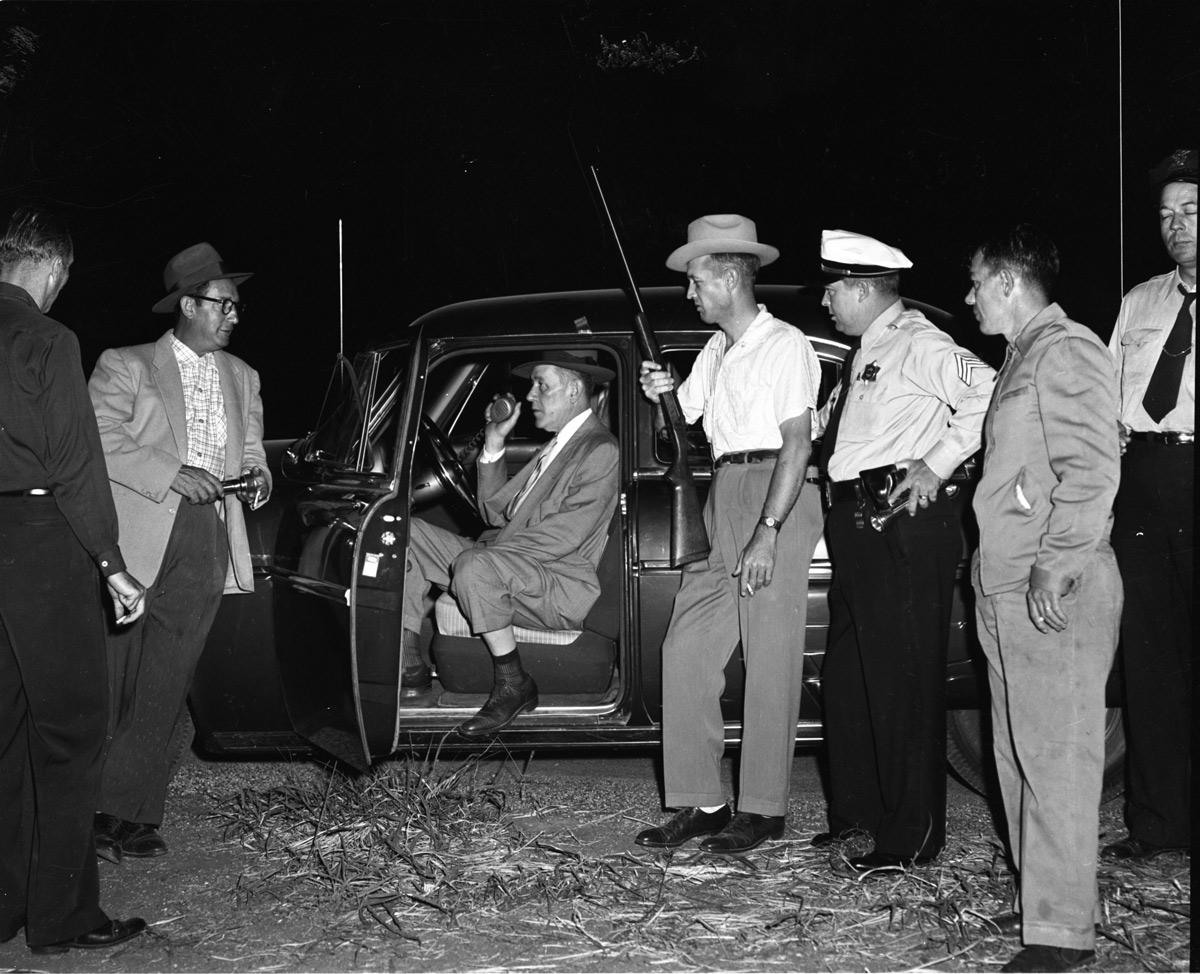

After several minutes, a Dallas police officer arrived. His story would be different. Patrol Officer J.W. Gallaher said that he leaned into the car, and, just before she died, Venice raised her head, coughed, and spoke to him clearly. She said, “A Negro took me under the bridge and cut my throat.”

Those words changed everything.

Overnight, the gruesome murder of the pretty, young white woman merged with the story of the Negro Prowler. Front pages shrieked of a city under siege, where gun shops sold out of weapons and the pound was overwhelmed with requests for large guard dogs. Women were afraid of being home alone. Armed men formed vigilante groups to patrol neighborhoods at night. Police begged citizens not to turn their guns on each other in fear. For weeks, tension built as the murder investigation, like the Negro Prowler case, went nowhere.

Police had found Venice’s purse, her broken glasses, and her underwear discarded on a patch of bloodstained grass at the bottom of a wooded ravine next to Lemmon Avenue. But 1950s forensics were very limited. The evidence in the ravine offered police virtually nothing to go on. Venice’s autopsy showed only that she had been raped and beaten and that she’d died after having her jugular vein severed. So under intense public pressure, investigators relied on a tried-and-true technique. They rounded up dozens of black men who had absolutely no connection to the case. One of those men was Tommy Lee Walker.

•••

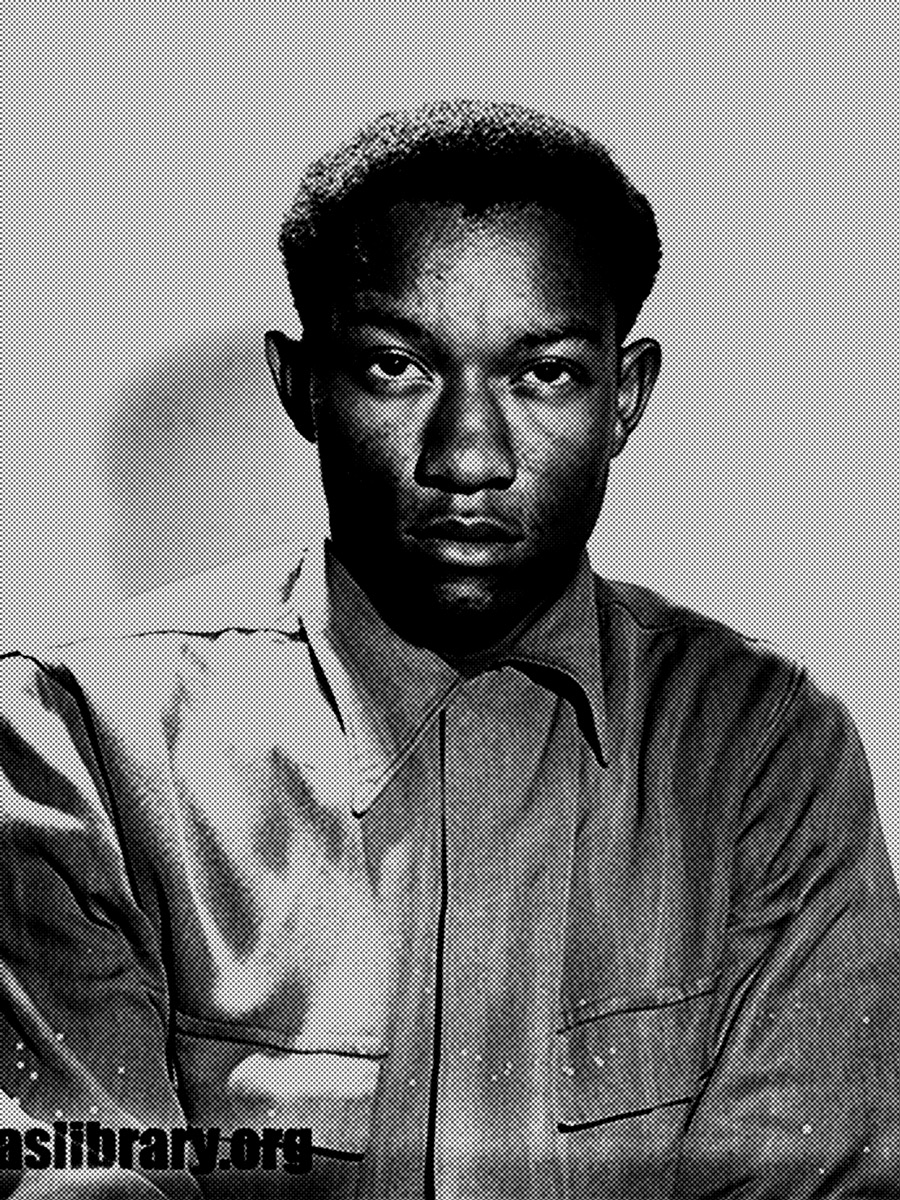

Tommy Lee’s life was already set to change profoundly on the night Venice Parker died. That evening, the 19-year-old’s longtime girlfriend, Mary Louise Smith, was about to deliver their child, something he was thrilled about. Friends said he’d pleaded with Mary Louise for months to marry him, but she refused because she wanted to wait until their baby was born. Preparing for fatherhood, Tommy Lee had been working extra hours at a gas station on Denton Drive, not far from Love Field.

One of his co-workers later testified that on the night of the murder he had driven Tommy Lee home at about 6, three hours before Venice was found, to what was then a burgeoning black neighborhood near Baylor hospital, east of downtown. Tommy Lee regularly needed a ride because he didn’t own a car. His home was about 5 miles from the scene of the murder.

The Walkers were longtime residents of the neighborhood around Exall Park, where his sister ran a beauty shop. Tommy Lee himself was familiar to many there as one of a group of young men who cooled off in the park in the evenings after work. They sang doo-wop songs and jokingly called themselves the Street Lamp Quartet. According to witnesses, Tommy Lee was there in the park for a couple of hours after work on the night of the murder. But he ended up, as he did most nights, at his girlfriend’s house near the park, arriving around 8 pm. He visited for a few hours and then went to his own house after 11 pm, two hours after the murder.

A few hours later, he got a call saying it was time. Mary Louise was in labor. He and his sister woke up their father and borrowed $5 to pay for an ambulance. Tommy Lee headed back to his girlfriend’s house, where he helped her into the vehicle. Their son, Edward Lee Smith, who goes by Ted, was born in the early morning hours, a little boy who would share his father’s middle name but very little of his father’s life.

The new baby came home to a city obsessed with its sudden lack of safety. Desperate to restore order, the police chief activated old World War II civil-defense teams, sending out 40 cars manned by citizens with ham radios, a move that backfired when self-proclaimed Prowler Hunters began to mass at every location where a possible intruder was reported. Police officers decried the citizen patrols for accidentally destroying important evidence, and reporters wrote that the patrols sometimes fired guns at “unusual noises or optical illusions.” Dallas police used the word “hysteria” to describe public reaction. The night after Venice’s killing, police received a whopping 400 reports of prowlers and peeping Toms.

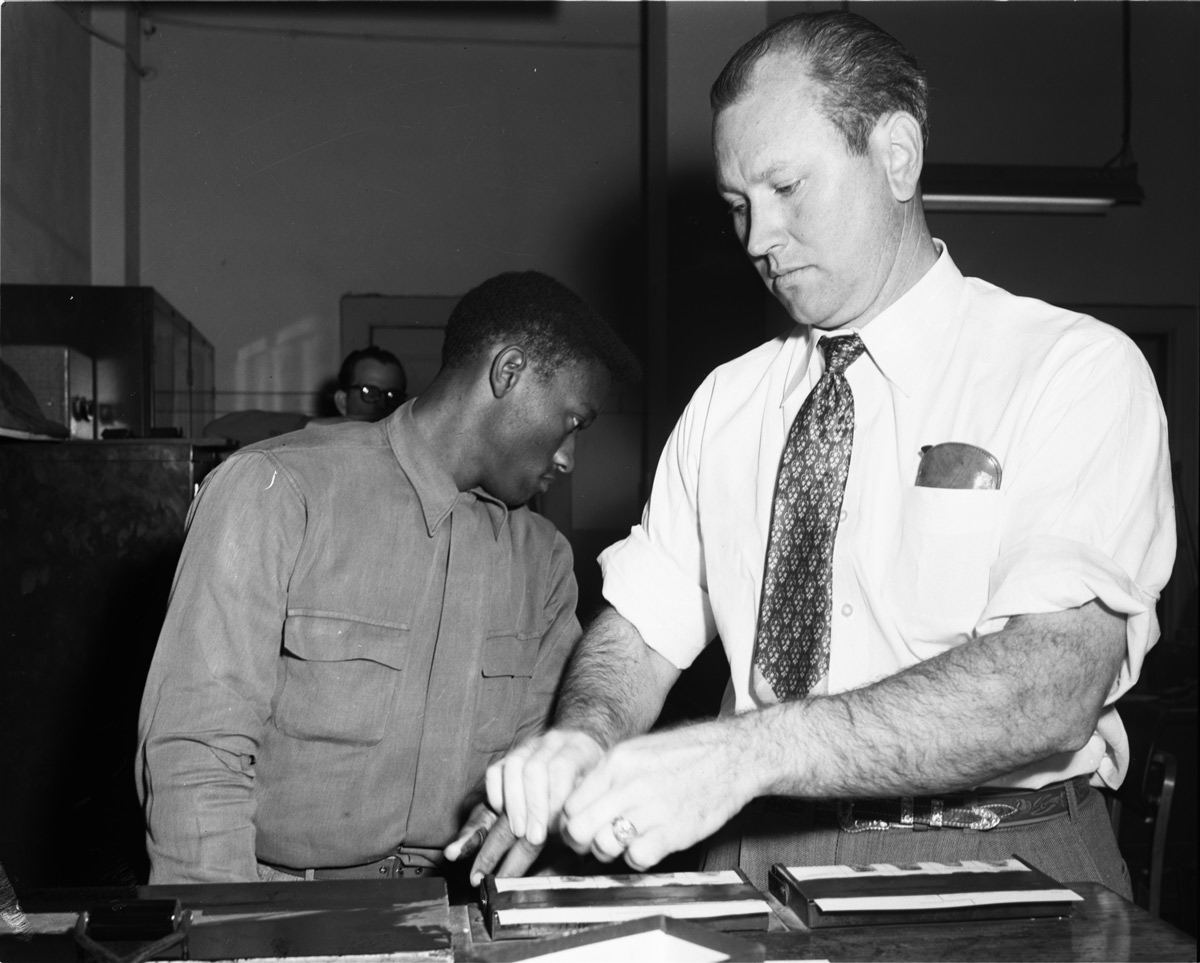

The cops began arresting young black men. Many were questioned for days after being picked up for “appearing suspicious” or for not being able to sufficiently explain to police where they had been on the night of the murder. Police also targeted men they’d had even casual contact with previously. The chief of the homicide unit, Captain Will Fritz, told reporters a few days after the murder, “We still have about 100 more Negroes to check on. We’ll investigate each one as we have time to get to him.”

Police didn’t get around to Tommy Lee Walker for four months, in late January 1954. The service station on Denton Drive where he worked had been robbed—months after Walker had moved on to another job. Police asked the station’s owner for a list of previous employees and their addresses, which led officers to Tommy Lee’s house near Exall Park. He was arrested and taken in for questioning on a Friday evening. While there, he later told friends and family, he feared for his life after seeing jail officers beat a black inmate.

Late the next night, Tommy Lee was brought before Captain Fritz, who questioned him for hours—not about any involvement in the robbery for which he had been arrested, but about Venice Parker’s murder. Tommy Lee said that Fritz told him he had received a phone call implicating him in the crime. Fritz had received no such call. Fritz said that there were witnesses and that police knew what he had done. Fritz had a reputation for being unusually effective at wringing admissions of guilt out of suspects, and his techniques worked in this case as well. Years later, we know much more about how often false confessions occur and what can trigger them—fear, cultural differences, sleep deprivation, and feelings of hopelessness, all of which played a role in this case.

Many hours later—alone, confused, and frightened—Tommy Lee wearily signed a confession for the murder. It included details about the crime that only police knew, along with a number of errors and information that simply didn’t add up. Tommy Lee, sensitive to issues of race and sexuality, insisted to Fritz that he hadn’t raped Venice Parker. The dubious confession claimed that the young mother had accidentally been stabbed when she “started to run and jumped into my knife.” Walker would say later that he didn’t see or hear the full transcript of the confession until it was read aloud in court during his trial.

As soon as Captain Fritz sent Tommy Lee back to his cell, the teenager realized the extent of the trouble he was in and began telling guards, inmates, and family members that he had been tricked into signing the confession. He said that everyone at the jail told him the same thing, that the only person who could help him now was the district attorney, Henry Wade.

A couple of days later, Tommy Lee met with Wade and renounced his confession in person. He told the DA where he’d been on the night of the murder, providing names of people who’d seen him from 6 pm, three hours before Venice Parker was killed, all the way till the early morning of the next day, when his son was born. Tommy Lee said that Wade told him he understood all of that and would help him—if he would sign a copy of the confession “for his files.” Tommy Lee claimed that Henry Wade told him it would be valuable for anyone trying to help with Tommy Lee’s case, and he promised that he would not ask for the death penalty.

There was no physical evidence linking Tommy Lee to the crime—no bloody clothing, no knife. None of Venice Parker’s belongings were found in his possession. There was no connection between Tommy Lee and Venice and no credible way to show that he had even been in the area at the time. Still, North Texas newspapers trumpeted the police success in nabbing the killer. Negro Prowler reports slowed to a trickle, and order in Dallas was restored, except in black neighborhoods, where people seethed over the framing of a naive kid who had proved no match for Henry Wade’s version of justice.

A young black attorney named Kenneth Holbert happened to be at the county jail that weekend, in the grand Beaux-Arts building on Harwood Street where citizens now pay their traffic tickets. Holbert was interviewing a client in the communal visiting area when he overheard Tommy Lee, distraught and protesting that he had been coerced into signing a confession for a crime he didn’t commit.

“His story was so striking,” Holbert says. “I thought, Not him. He’s not big enough to do that. He was a small fellow, about 5-foot-3, weighed maybe 118 pounds. My first thought was, What is this kid doing in jail and what can we do to get him out?” Holbert went back to the law office where he worked for W.J. Durham, one of Dallas’ first well-known black attorneys. He told him about the Tommy Lee Walker case, and, after some back and forth, eventually the team agreed to represent him at trial.

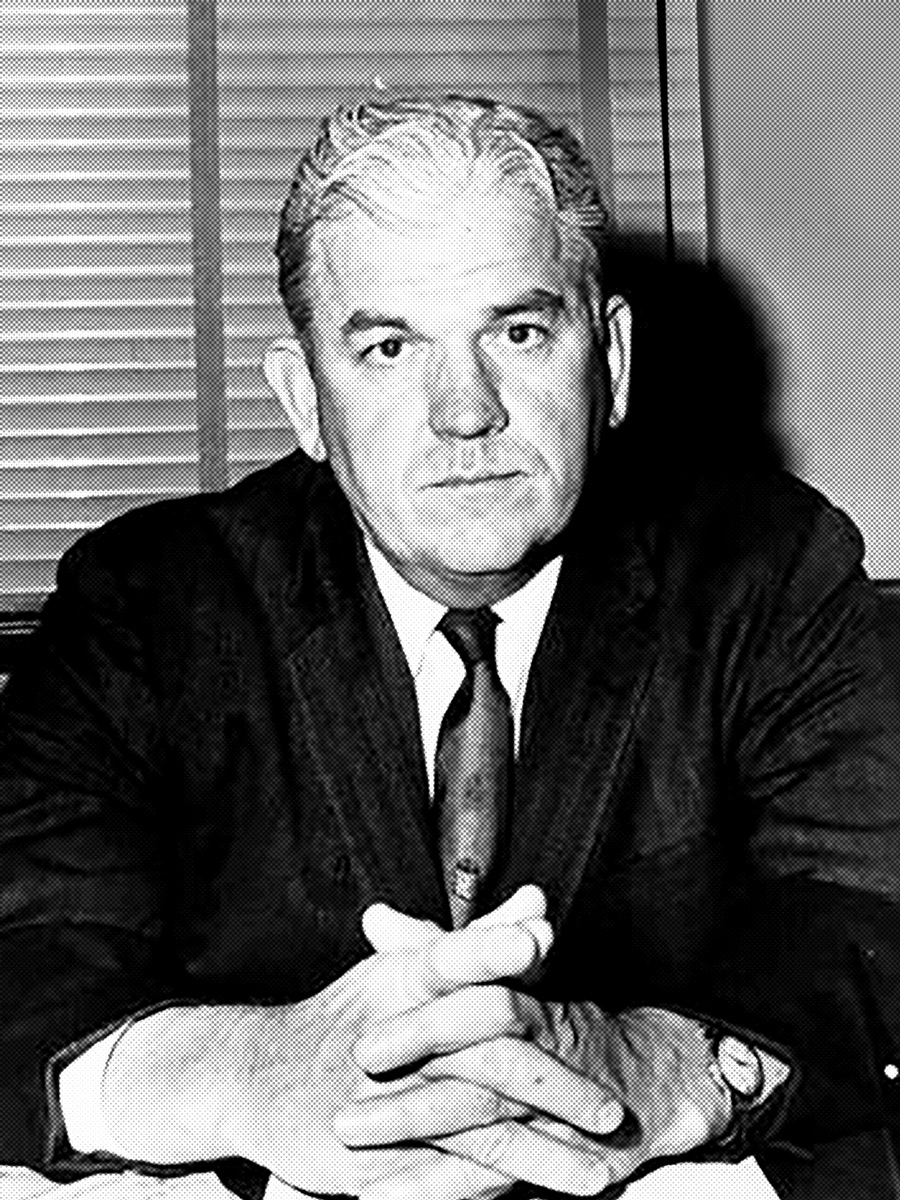

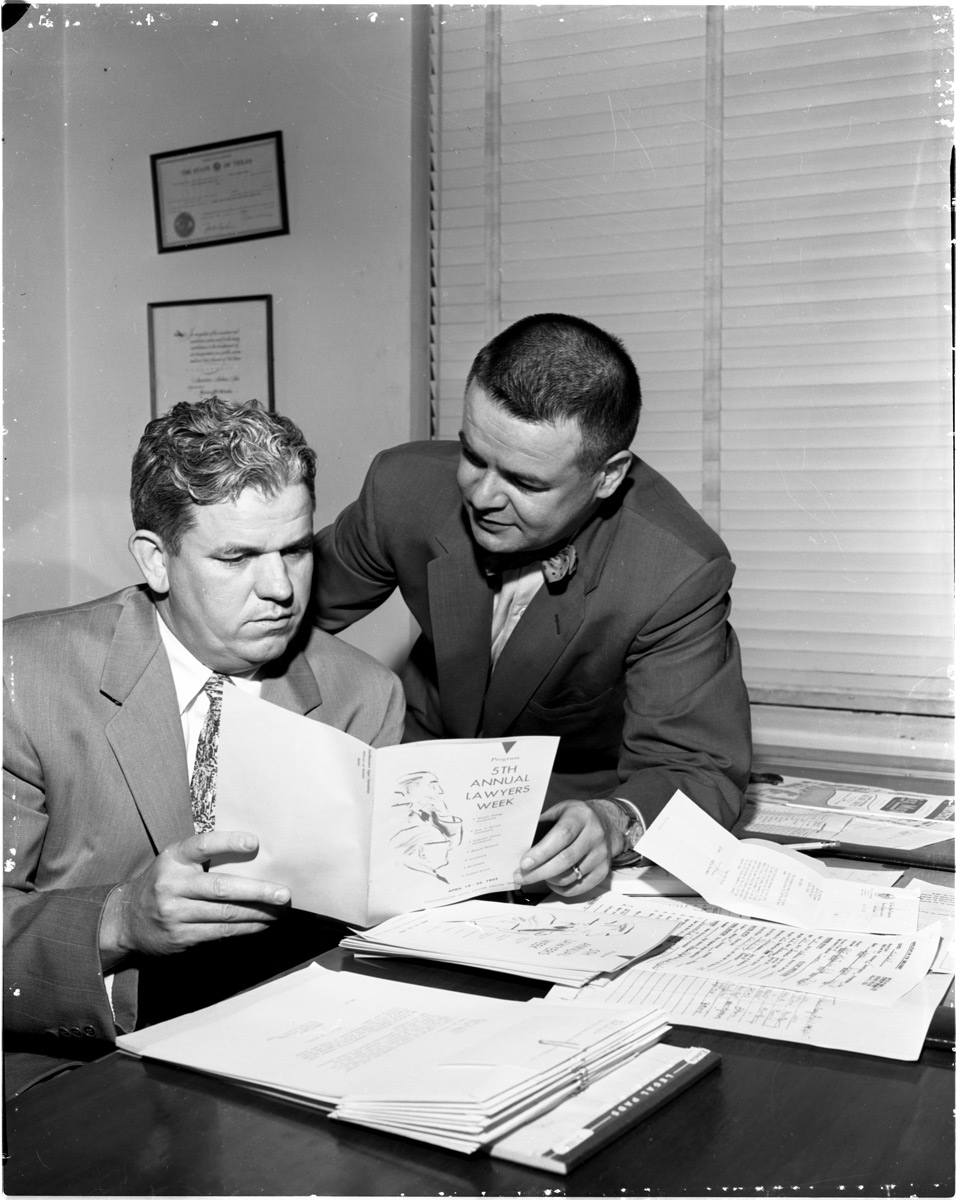

Holbert, Durham, and J.L. Turner, another Texas legal giant, joined forces in presenting Tommy Lee’s defense, three black lawyers in a life-or-death face-off with the daunting forces of Henry Wade and his staff. “He was all about winning,” Holbert says. “He was a brilliant attorney. He got the maximum that was available. The maximum is what he always got.” The defense attorneys felt they had no chance of winning an acquittal against Wade in front of an all-white jury. They hoped to save their client’s life. “In those days, what you tried to do was get a lighter sentence in the murder of a white female. You didn’t expect to walk him out. Best bet was to create something akin to doubt. Back then, that would be your victory. Life in prison, not death. That would be your victory.”

•••

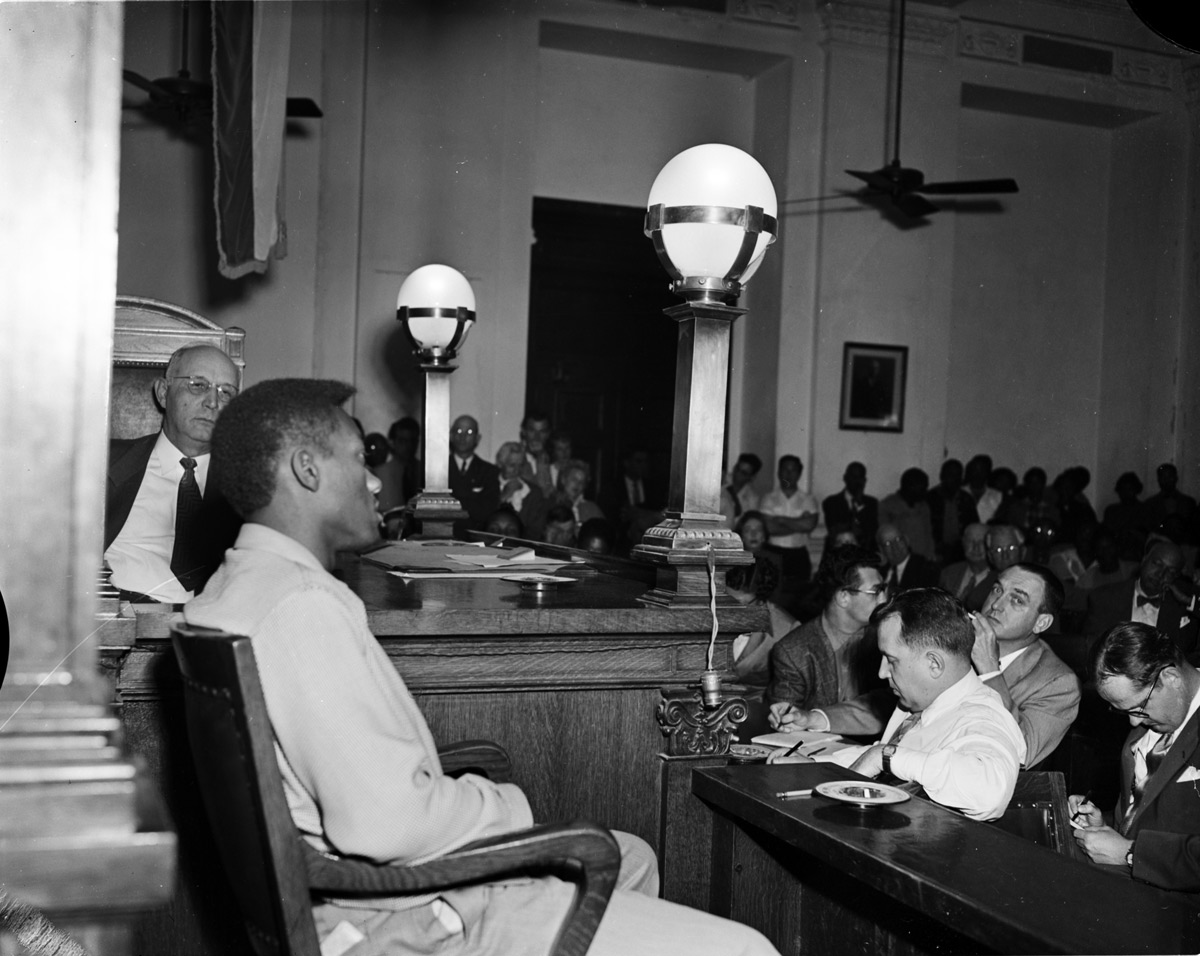

The trial, in March of 1954, became a sensation, with black newspapers covering it as closely as the larger publications. Every day the courthouse was packed with scores of black onlookers, many of whom had to wait outside in the hushed hallways because there wasn’t space in the courtroom. They strained to hear testimony through cracked doors, struggling to glimpse the overflowing benches and players in what many believed was an unfolding travesty.

Henry Wade called two surprise witnesses who said they had been driving through the area on the night of the crime. A man and woman, both white, had come forward after Tommy Lee’s picture had appeared in the newspaper. Mrs. Harry Kluge told the jury she had seen a “colored man walking along on the sidewalk … . [H]e sauntered along and walked in the direction of the bridge.” A male driver who said he stopped at a traffic light near the murder scene testified that he “noticed a colored man leaning against the telephone pole, in a slouched position.” He claimed that at the moment he’d seen him, he’d told his wife that the man “was a good prospect for the Negro Prowler.” Despite the darkness of the hour, despite the distance, despite the passage of time, both said that, in their opinion, Tommy Lee Walker was that man. Any understanding of the failures of eyewitness identification, particularly across racial lines, was far into the future.

The defense team countered with no fewer than nine alibi witnesses. Tommy Lee’s girlfriend, Mary Louise Smith, told the jury that her boyfriend had been at her house at the time of the murder. “District Attorney Wade tore into her testimony,” according to the Dallas Morning News. He claimed that Mary Louise had told Captain Fritz in an earlier interview that Tommy Lee hadn’t been there. Both Mary Louise’s mother and their next-door neighbor testified that they had talked to Tommy Lee when he was at the Smith house that night, close to the time of the murder. The co-worker who’d driven Tommy Lee home from his job at the service station testified on his behalf. So did the Beard brothers, who’d been with him in the park that evening. A beauty shop worker who saw him at his sister’s salon before he walked to Mary Louise’s house testified for him. The ambulance driver told the jury that Tommy Lee had been at the Smith house when he arrived to take Mary Louise to the hospital. Tommy Lee’s sister testified that she had seen him early in the evening and was with him at home later, when they’d awakened their father to borrow ambulance money. None of that testimony—accounting for Tommy Lee’s whereabouts during every hour of the night, putting him 5 miles from the murder—and none of those witnesses swayed the all-white jury.

Tommy Lee’s attorneys brought in skycaps and other witnesses to testify that they had not heard Venice Parker speak when she was in the car at the airport. The attorneys repeatedly challenged the patrol officer who claimed that she had told him, after convulsing in the car, after spilling her blood in the back seat, “A Negro took me under the bridge and cut my throat.” They introduced expert medical testimony that it would have been impossible for her to speak because of the severity of her injury. And they tried to keep Tommy Lee’s confession out of court, claiming that it was coerced and signed without appropriate warnings. They argued that his arrest had been illegal. On all counts, the court ruled against them.

Tommy Lee Walker took the stand. He told the court that after fighting Captain Fritz’s demands for hours, he finally gave in and told him what he wanted to hear because he was scared. To counter that claim, Henry Wade brought two reporters from the Dallas Morning News and WBAP radio to the stand to testify that they had watched Walker sign the confession and that no one appeared to threaten him in their presence.

Then Henry Wade made his signature fiery closing argument. He stalked the courtroom, slamming his hands on the defense table and thundering directly into Tommy Lee’s face, “I’d be glad to walk the last mile with you, Walker. And I’d be glad to pull the switch on you.” The jury went to deliberate.

“We left to go to a restaurant to get a sandwich,” says Holbert, the defense attorney. “Before the order was brought to our table, the bailiffs showed up to say we had a verdict.” It had taken just over an hour for the jury to reach a decision.

When Holbert and the defense team returned to the courthouse, it was surrounded by close to 1,000 black citizens, who were in turn surrounded by dozens of Dallas police riot officers. Holbert says, “That moment was the most powerful example of state power I have ever seen.”

Inside, just three months after he’d been arrested, Tommy Lee Walker was pronounced guilty and sentenced to death.

•••

Tommy Lee Walker’s prison records show that in his first interview at the Walls Unit, in Huntsville, Texas, he again insisted on his innocence. “I signed a confession … because I was frightened and tricked into it. I was over 2 miles from where this murder was supposed to have occurred on Lemmon Avenue. Never at any time was I in this area on the night of September 30, 1953.”

In his assessment of Tommy Lee’s attitude, the examining officer wrote, “Subject is of the opinion that he did not get a fair trial … . He has an excellent memory for events past and present, however, the interviewer found him to be very evasive and impudent … . This subject denies guilt … DISPLAYED A POOR ATTITUDE.”

In Tommy Lee’s last psychiatric examination before he was executed, a doctor wrote that he “revealed no depression, irritability and no anxiety… He did state the law knew he was innocent and that they were framing him.”

“Henry Wade wouldn’t intentionally try to convict someone he knew to be innocent,” says former Dallas assistant district attorney Edward Gray, “but even in cases where evidence was weak, he would go all out, go for broke, be super-competitive.” Gray, who wrote the 2010 book Henry Wade’s Tough Justice, which begins with his years working in the Wade office, says that the Tommy Lee Walker case “was not at all out of character.” In the years since DNA forensic technology has been improved and utilized to re-investigate Dallas County criminal cases, at least 25 convictions that Henry Wade oversaw have been overturned, according to the National Registry of Exonerations, with one caveat. They did not start tracking wrongful convictions until 1989. It is possible that there were some convictions overturned before that. Some of the men who were wrongly convicted had been on death row. But there has yet to be a DNA-based exoneration of someone who has been executed.

Shortly after midnight on the appointed day, Tommy Lee Walker was led to the electric chair and strapped in. He declared one final time that he was innocent. Four minutes later, he was dead.

His body was displayed in a small South Dallas funeral home for two days. More than 5,000 people walked past his cardboard casket in protest. The Dallas Express, a black paper run by Marion Butts, listed the name of every person who came to the viewing. On the day of the funeral, Butts wrote a searing column condemning the handling of the case. “Walker is dead,” he wrote, “but he will forever live in the minds and conscience of those who have the ability to reason.”

•••

Joe Parker has only one real memory of his mother, Venice, and he cries every time he shares it. He recalls how happy it made him, as a 4-year-old, when his mother arrived after work to pick him up at his grandparents’ house.

“We would walk home at night, about a half-mile or more,” he says. “And I remember walking along with her, holding hands, and watching our shadows in the streetlights. I remember being struck by how much bigger her shadow was than mine. And I remember looking at the shadow of our hands clasped together.”

Looking at old newspaper articles about his mother’s death, he shakes his head. “With the all-out prowler stuff and roaming bands of vigilantes, that’s out of the Wild West,” he says. “You probably had Klan activity and everything else. I’m surprised they didn’t just jerk somebody out and hang them. Ten years earlier, they might have.”

Parker says in grade school he was bullied for what had happened to his mother. “A kid said, basically, a black man raped your mother, and that means you’re half-black. I was 6 or 7 years old,” he says. “I was too young to understand anything about it.” His grandparents had him transferred.

His voice trembles when he talks about how he discovered late in life that Venice was studying to become a graphic artist. That’s what he became. He sighs deeply at what he sees as a bond with her.

In their attempt to keep the tragedy from overwhelming his life, Parker’s grandparents didn’t talk about his mother. “Anytime something came up about my mom, that pretty well got shut down—and my father, too, for that matter,” he says. “Looking back, there must have been some hostility between my father’s side of the family and my mother’s side. I don’t ever remember meeting my father.”

Harry Parker disappeared from his son’s life shortly after his wife was killed, for reasons that remain unclear. He had made a similar choice with an earlier family tragedy in Arkansas. When Harry Parker’s first wife died after a brief illness, he left behind a young daughter who was raised by her grandparents. He did not have contact with either child before his death in 1961 of tuberculosis.

Joe Parker visited Italy to see Venice, the city his mother was named for, a name she shared with her own mother, the woman who raised him after the murder. “My mother and my grandmother’s nicknames were Vesuvius, because they both were high-spirited women,” he says. “I went to Pompeii and walked the rim of the volcano.” It was his way of connecting to them long after they were both gone.

He says that Tommy Lee Walker’s case raises questions for him, too. “The fact that his son is still alive, you know, if his father can be cleared, I think that would be a great thing,” Parker says.

•••

At the Dallas funeral service for Tommy Lee Walker, the minister told a packed church that just hours before his death, Tommy Lee had told his father that he “was not worried about what he was facing, because God was with him.” In the front row, Tommy Lee’s sister held his 2-year-old son, the child he’d had with Mary Louise Smith.

Even though he was young, Ted Smith says he believes he remembers fragments of that day. “I remember the casket,” Smith says. “And Aunt Willa Mae, she had me on her lap, and she was holding me, and she wouldn’t let me go. My mother couldn’t even get me from her.”

Smith and his wife of 38 years live in a small frame house in South Dallas, filled with silk flowers, pictures of their three sons, and painful memories. Smith says his childhood was hard and that his mother spent the rest of her life mourning Tommy Lee, never marrying, drinking too much, and dying from an aneurysm at age 52. He says she cried about her boyfriend’s execution almost every day. “My mother constantly put it in my mind,” he says. “ ‘They took your daddy away. They killed him for nothing. He was an innocent man.’ We carried that grief together.”

In the childhood fog of his early years, Smith says, he didn’t understand the circumstances of his father’s death. When his mother told him his father had been electrocuted, Smith thought there had been an accident. “Like he was working with electricity and got shocked. That’s what I thought,” he says, “until years went on and my mother told me exactly what happened, when I was about 10 or 11.”

The loss of his father remains the defining event in Smith’s life. It drove him years later to visit the Texas Prison Museum in Huntsville to stand before the chair where his father and 360 other men had died. He remembers the hurt he felt as a child when other kids would talk about the fun things they did with their fathers. He sobs when he recounts even mundane conversations about his family. “It’s hard when you have to tell people who ask, ‘Well, how did your father die? When did your father pass away?’ And then I have to tell them, ‘My father died in the electric chair.’ It’s hard.”

But Smith, now 62 years old, recounts with pride how, throughout his life, people who knew his father have made it a point to share their memories. “Old men would say, ‘Do you know who this boy is right here? That’s Tommy Lee Walker’s son.’ Then they’d all of a sudden just hug me and start crying. ‘You had a good daddy. Me and your daddy, we used to play baseball together. In Exall Park, we had glorious days there, singing. Your dad wasn’t a violent person. He was a good person.’ ”

Ted Smith wipes his tears with the back of his hand and sighs. “It matters to me,” he says. “It may not to other people, but it matters to me. It does matter.”