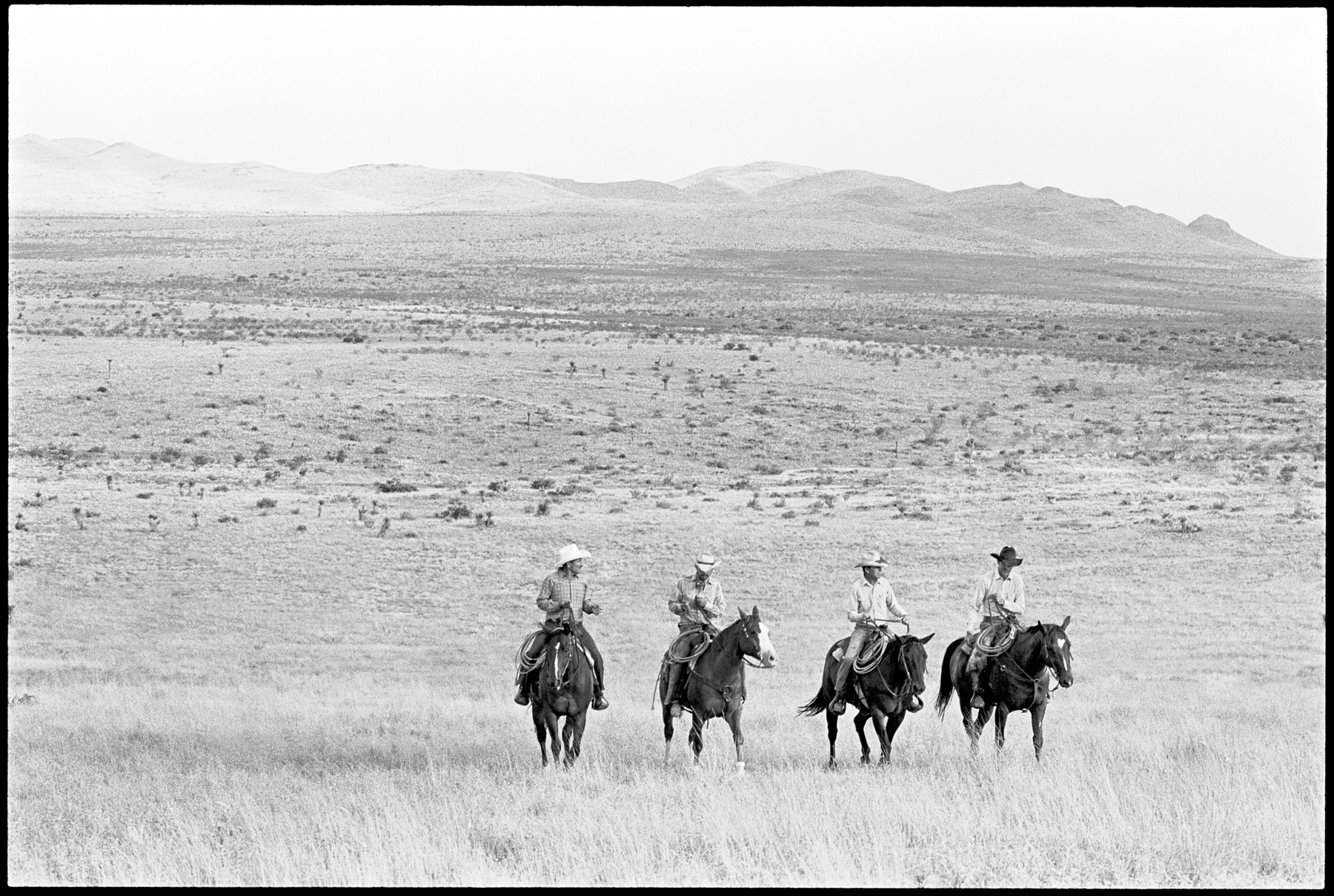

The image of the horse with the small white splotch on its brow comes from the Y-6 Ranch in Valentine, Texas. The ranch—as photographer Laura Wilson explains in her new book, That Day: Pictures in the American West—is about as far from the world as you can get without dropping right off the face of it. In another image from Valentine, ranch hands sit atop their horses, framed by a landscape that feels as desolate and alien as the hazy red mountains photographed by the Mars rover.

“I was drawn to people who live in an enclosed world,” Wilson writes in her book. “Those people who live in isolated communities, whether by circumstance or accomplishment.”

It was a journey that began in 1979, when she first worked with legendary photographer Richard Avedon on his own series about the West. The fashion photographer’s unique approach had Wilson scurrying around tiny towns, scouting for faces that Avedon would then capture in isolation, framed against a white backdrop, emphasizing all their rugged, gothic expressiveness. Wilson’s own project retains some of this grit but expands the focus. In her photos there is a stark realism that plays in tension with the way these subjects and settings resonate with the myth of the West.

The idea for the retrospective exhibition began not in isolation but at a cocktail party in Wilson’s home on Strait Lane in October 2011. That’s where Andrew Graybill, the new co-director of the William P. Clements Center for Southwest Studies at SMU, saw one of Wilson’s images framed in her dining room. Seeing the image in that setting, Graybill notes in his foreword to That Day, showed “a West that is unfamiliar and riddled with paradoxes.”

Dallas’ own relationship to the West is one of paradox. A frontier town shaped during westward expansion, it is a Southwestern city whose civic ambition and desire for cultural sophistication found it often looking eastward for inspiration. It is not surprising, then, that it is through Wilson—a native New Englander who has lived much of her life in Dallas—that the West takes a form that feels both familiar and foreign, exploiting photography’s power to convey a sense of intimacy with subjects we might otherwise avoid or not notice.

In the following pages, we have reproduced a selection of photographs from That Day: Pictures in the American West, accompanied by Wilson’s own words, in celebration of her career. From the realities of immigration and the fervency of evangelical Christianity to the enduring appeal of the man who first drew Wilson to the mysterious West, her images reveal a contemporary landscape that, though seemingly remote, participates in the shaping of our own. —Peter Simek

Y-6 Ranch

I photographed the Means men apart from the women, the father and son each with a vaquero, or cowboy. The men spoke Spanish mixed with English among themselves. They were out on the land all day, working cattle, providing supplementary feed, tending water pumps—whatever it took to squeeze some value out of 60,000 acres.

I photographed the women with their husbands, but the stronger portrait seemed to me to be the one of the women and girls together, separate from the men. On the Y-6, the women led more traditional lives within a domestic setting. They tended to their families and kept their households running, and on the Y-6 that’s a big job—it is, after all, a 120-mile round trip to the closest grocery store in Alpine. To ward off the isolation in their lives, there was a necessary closeness among the generations. —Laura Wilson

The Border

I’ve been paying attention to border issues for a quarter of a century now. I’ve seen Mexico’s various attempts to build some kind of democracy fail, and I’ve despaired at the continuing rise of corruption in the government, enabling narcotics to become that country’s primary export. Corruption, collusion, and poverty have combined to make the country incurably unstable and the border with the United States una herida abierta, “an open wound.”

The writer Gloria Anzaldúa speaks of the border as a place “where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds. And before a scab forms it hemorrhages again, the lifeblood of the two worlds merging to form a third country—a border culture… . The prohibited and the forbidden are its inhabitants.” —L.W.

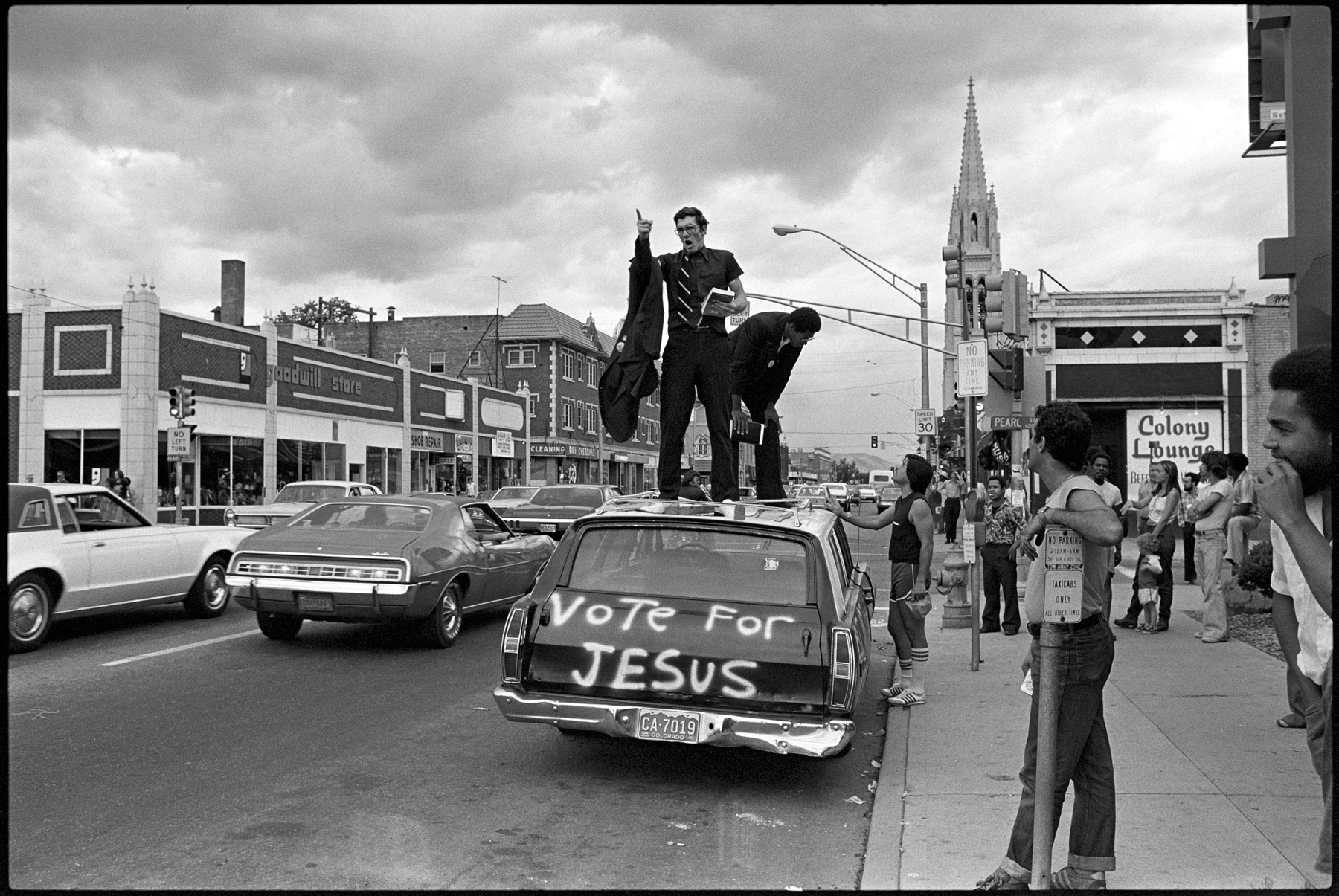

God’s Frontier

The popularity of the Glory Riders seemed to me to be a reflection of the growth of evangelical and Pentecostal groups. Over 15 years, on frequent drives on the highways and byways of the West, I watched the expansion of the fundamentalist Christian frontier. The number of small places of worship seemed to triple. They often lacked steeples and stained-glass windows, but they always had a cross. —L.W.

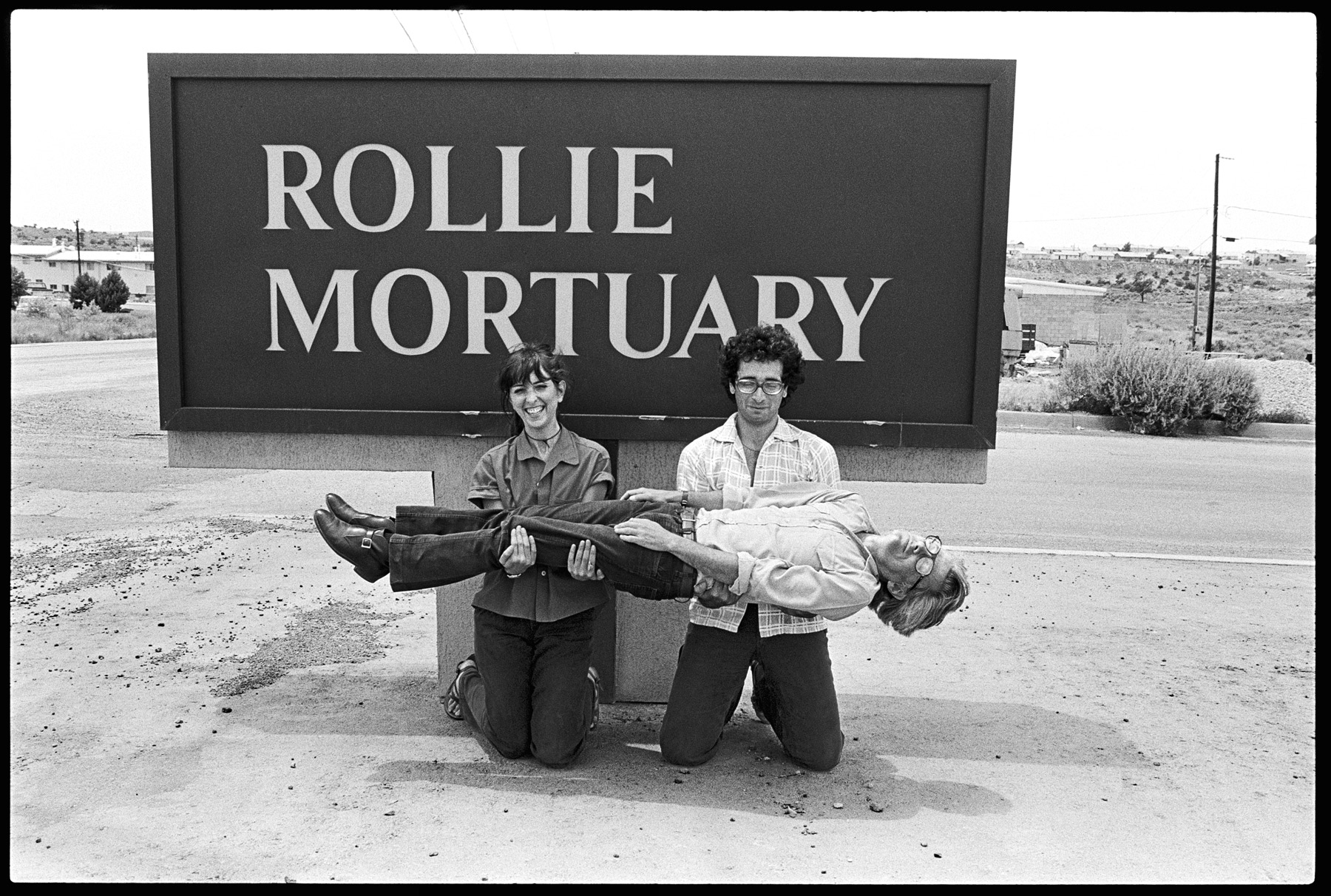

Avedon

In 2004, when Avedon was 81 years old, he asked me to help him once again, this time with a project for The New Yorker. He wanted to return to the West to round out a series of portraits he called Democracy. We spent two days at Fort Hood in Killeen, Texas, and then went on to San Antonio to Brooke Army Medical Center, the U.S. military’s leading burn-treatment facility.

That night, Avedon and I made plans to meet the next morning to review his layout of the story, but when I went to his room early that following day, I found him unsteady and confused. He said sadly, “I couldn’t sleep. I kept seeing the burnt faces of the soldiers, even those bandaged faces I could not see.”

Moments later, he lost consciousness. He had suffered a stroke. He was rushed to Methodist Hospital in San Antonio but died of a cerebral hemorrhage there five days later. Avedon’s life as a photographer was far-ranging and obsessive. Right through to his last portraits for The New Yorker, he never stopped working. And he got his wish to die in the West, although not under the Rollie Mortuary sign. —L.W.