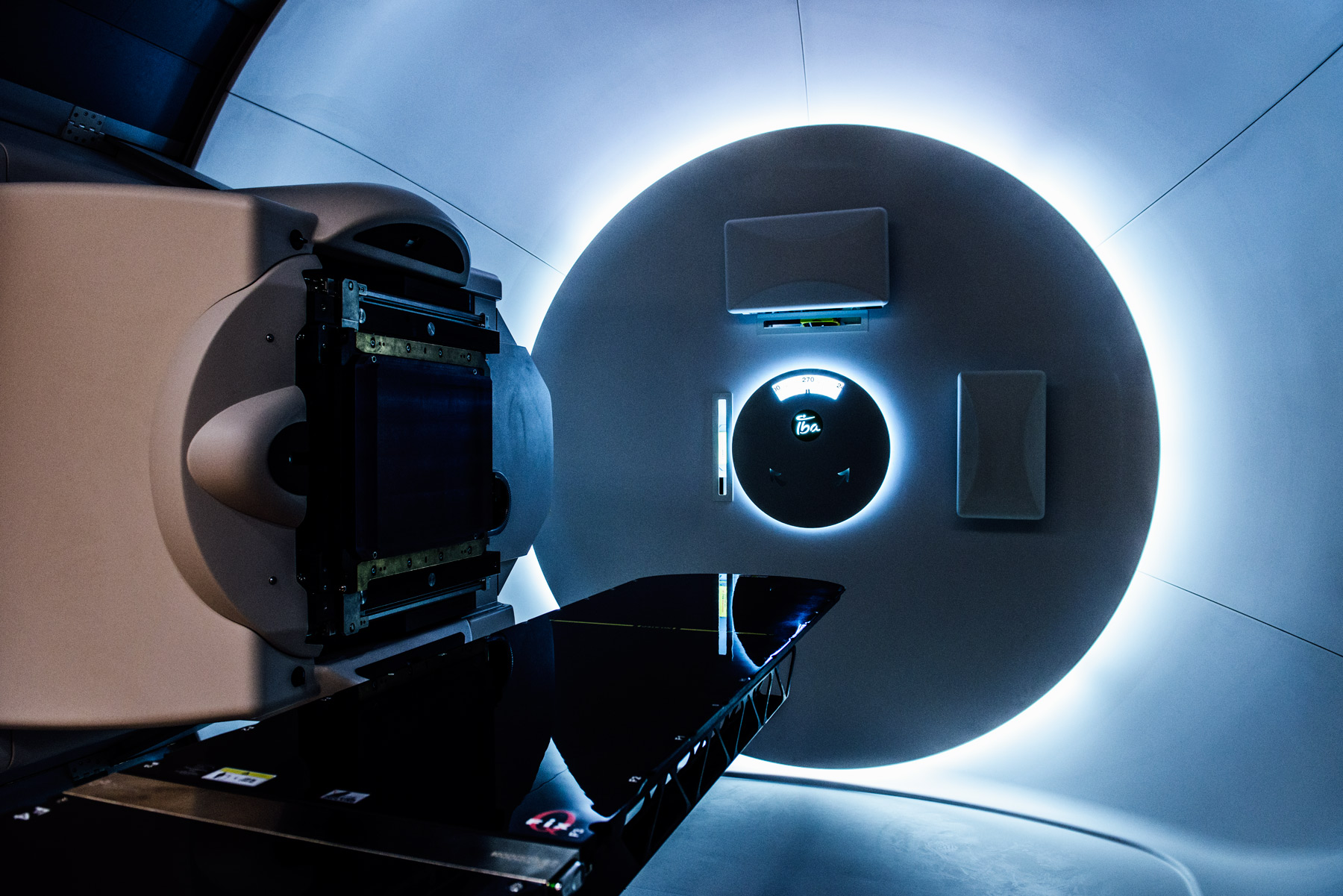

The beam being fired into your body isn’t big. Its precision can be measured in millimeters. The machine that’s generating it is hidden somewhere in this building behind walls of concrete that are up to 13 feet thick. You’re in a treatment room, lying in the middle of a three-story-tall gantry machine that looks like it could be a piece of a James Turrell installation.

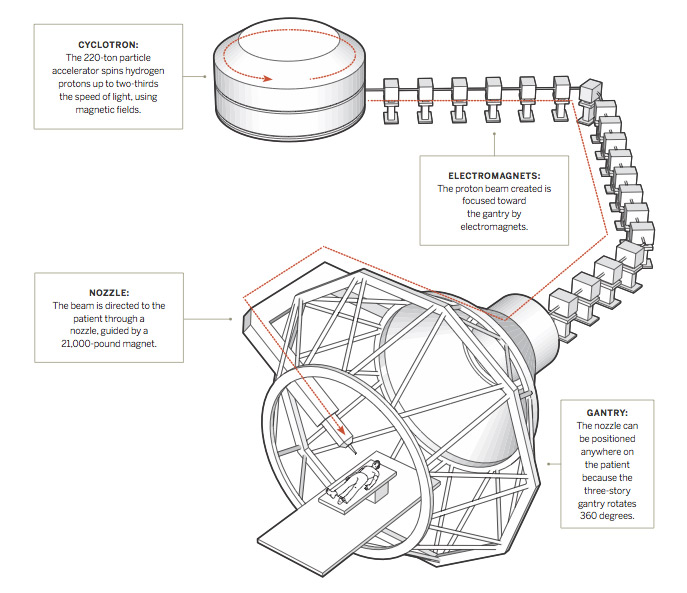

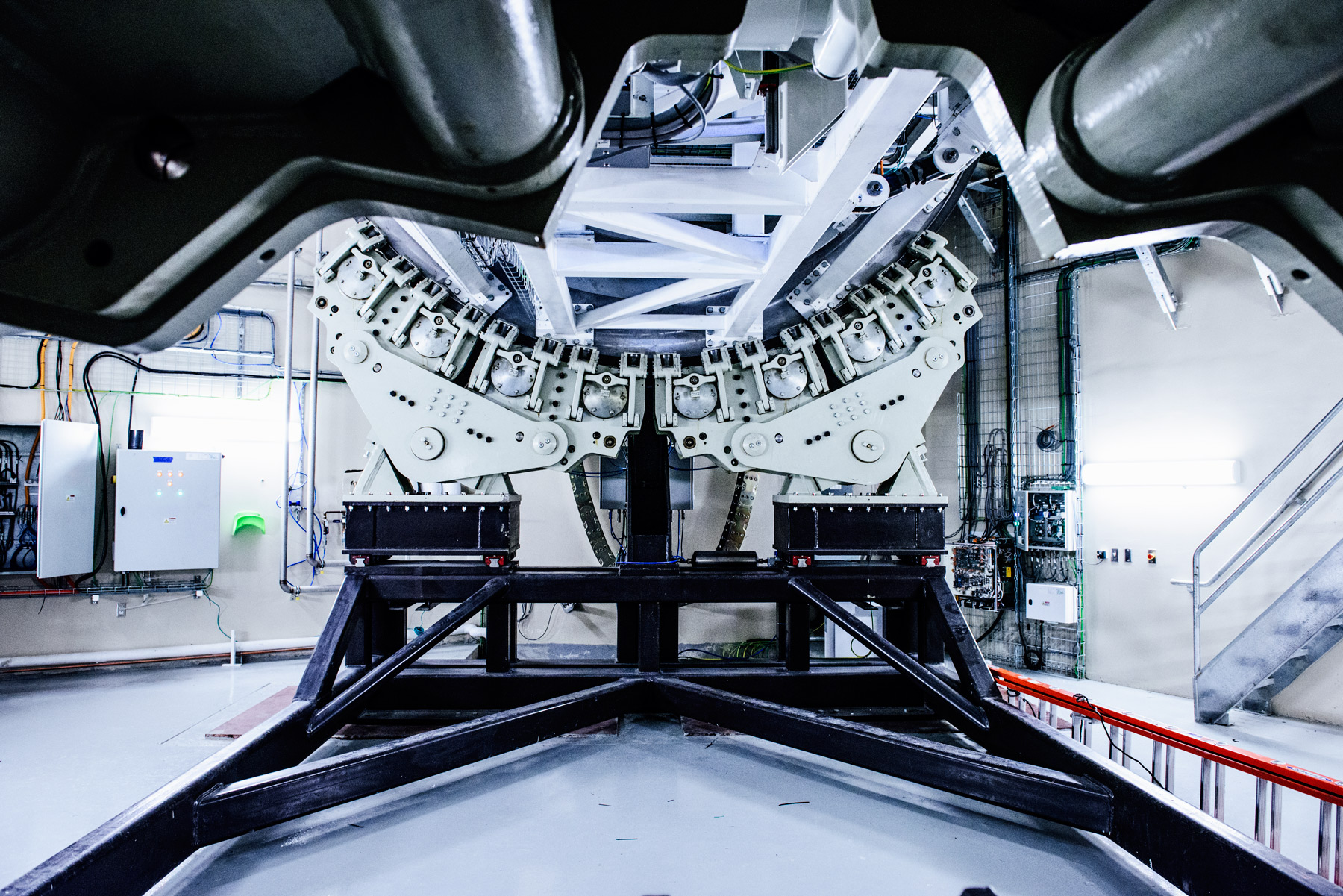

In another room is a 220-ton particle accelerator called a cyclotron that whips protons at two-thirds the speed of light to create that tiny beam of concentrated radiation. To get to you, it travels about half the length of a football field, in a 143-foot line. When it’s diverted into your treatment room, if all goes according to plan, the powerful beam is directed to the tumor and misses most, if not all, of the healthy tissue around it.

There are options in Houston and Oklahoma City. But at a distance of 245 miles and 222 miles, respectively, those cities present problems. The distance and time (treatment often takes five to eight weeks of daily sessions) make the proposition a tough one for those who are most vulnerable to traditional radiation: children and the elderly. Texas Oncology, the U.S. Oncology Network, Baylor Scott & White Health, and McKesson Specialty Health noticed this gap and in 2012 announced plans to form the Texas Center for Proton Therapy in Las Colinas. In all, it cost $105 million to build and will be able to treat 100 patients during a 16-hour day. It can take about 13 seconds to send the beam from one of the three treatment rooms into another.

Its staff cumulatively has 65 years of proton experience, a substantial amount for a new center. It already offers imaging services to patients and should provide the therapy by November. It will also have at least an 18-month head start on UT Southwestern Medical Center, which plans to open its Dallas Proton Treatment Center in 2017.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that all the leading cancer centers are going to offer proton therapy,” says John Frick, interim executive director of the Maryland-based National Association for Proton Therapy. “It’s not a silver bullet. It doesn’t cure every problem, but right now it’s the best radiation tool available for treating solid tumors.”

Now, six years later, that cost predicament remains. Even supporters agree that the up-front price of proton therapy is much higher than more traditional or readily available treatment options. It also is more effective for cancers near sensitive tissue like the brain, spinal column, or eye. Insurance companies have been increasingly reluctant to pony up the money to use it in treating more common cancers like prostate, which for years was one of the most oft-referred for proton therapy. In 2013, Dr. Durado Brooks, director of prostate and colorectal cancers at the American Cancer Society, wrote, “[T]here is at present no convincing evidence that urinary (bladder problems), gastrointestinal (rectal leakage or bleeding), or sexual (erectile dysfunction) complication rates are lower following proton therapy.”

Aetna, Cigna, and UnitedHealth each vowed to stop paying for proton therapy to treat prostate cancer, citing the availability of cheaper, proven methods. A 2012 study published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute found that the therapy can cost about twice as much. The median Medicare reimbursement came in at $32,428 for proton-beam treatment of prostate cancer, compared to $18,575 for traditional radiation therapy. But research published in 2014 and 2015 sided with proton therapy, finding that higher initital costs were outweighed by long-term savings by reducing chances of developing secondary cancers.

The man responsible for the clinical aspect of the Las Colinas facility has seen this argument play out firsthand for years. Dr. Andrew K. Lee launched MD Anderson’s proton program in Houston and has more than 14 years of experience in this realm. He has been spending time at tumor boards—where oncologists in a practice confer about patients’ diagnoses and potential treatments—throughout North Texas and making rounds at the Texas Oncology–Baylor Charles A. Sammons Cancer Center, spreading awareness of what will soon be available. The center has a team dedicated to advocating for the patient in cases where there’s pushback from payers. And nearly all of his physicians have a background in pediatrics, in addition to the proton experience, providing a solid foundation for children with complex tumors.

Yes, there’s concern about an abundance of competition and overbuilding; after all, it took more than 24 years to get 17 of these online, and another dozen will be active by 2017. One in Indiana closed last year, although Frick notes that its founders bought used equipment that wore out much quicker than the 40 or 50 years it typically takes before a new cyclotron needs attention.

But the biggest positive in our local center’s corner may be the sheer size of North Texas. Nearly 7 million people call Dallas-Fort Worth home, and more are coming each day. They’re also aging. Last year, about 116,000 Texans were diagnosed with cancer. Lee predicts the demand for the therapy may actually surpass supply here. That’s what drives him. That and something a bit simpler: he believes in the technology.

“When I saw the infrastructure that Texas Oncology, McKesson, and Baylor Health developed, I thought it had a high chance of actually achieving what the original intent was,” Lee says. “And that is to make proton therapy accessible to a larger group of cancer patients.”