Patterson began to think about leaving London right about the time the Dallas Museum of Art offered him a Concentrations exhibition in 2000. He and Rae had moved into a Corbusier-inspired high-rise, with floor-to-ceiling windows that offered a spectacular view of the center of London. Downstairs, there was a choice of two motorcycles: a 1968 BSA Spitfire MkIV and a 1997 Triumph T509 Speed Triple. There was a long waiting list for his paintings. Charles Saatchi was buying his work, and he included him in the celebrated Sensation exhibition. But in the haze of success, he and Rae were drifting apart. “The dynamic in our relationship changed so sharply,” he says.

When things became particularly tense between the couple, she kicked him out, and Patterson moved into his studio in Hoxton, which didn’t have a bathroom. One night, he found himself lying in the bathtub in Gary Hume’s studio under a little barred window that looked out into the dim alley, listening to two men beat someone up in the alley. London was in the midst of an economic boom, but Patterson felt like his London was slipping away. The art world had brought him money and fame, but it had stolen friends, the love of his life, and something of himself. Maybe, he thought, it was time to leave.

The thought of Dallas as a destination never crossed his mind, but when he came to town for the DMA show, someone in Dallas caught his attention—Christina Rees, then the Dallas Observer’s art critic (who would go on to work at D Magazine). There was something immediate and intellectually intense about the chemistry between Rees and Patterson. As it turned out, the young art critic was already planning to move to London, and within months the two were living together back in London.

The first few years of the century were particularly difficult for Patterson. His father passed away, and Anthony d’Offay abruptly closed his doors. Patterson was left without a London gallery, represented only in New York by James Cohen, who had worked for d’Offay. The new couple decided to move to New York. They arrived right after 9/11, and New York no longer resembled the city Patterson had loved to visit. They moved from the East Village to Chelsea to Brooklyn, but never quite settled. Finally, in 2004, Patterson and Rees moved back to her hometown, finding a house on a quaint sidewalk-less street a few blocks from White Rock Lake.

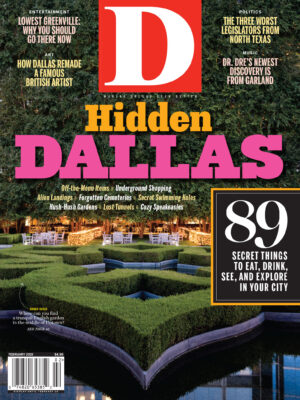

The art world can understand a European artist moving to New York, but no one understood Dallas. Some speculated that Patterson was drawn to the kitsch culture of cowboys and cheerleaders and the other sexualized manifestations of American consumer culture that often turn up in his paintings. “I’m the guy who likes flashy cars, so they thought I wanted to come here and drive monster trucks,” he jokes.

But what drew Patterson to Dallas was what draws so many people to this city: its space and sense of possibility. It was a place where the rigor and rules of the art world didn’t hold artists tightly bound. Patterson was attracted to the idea of disappearing in a city on the periphery of the art world. “I thought that making art in the most unlikely place in the world might make things clearer,” he says. And he wanted to make a decision for once in his life that wasn’t dictated by the demands of his career. “You felt owned,” he says of signing with a big gallery like d’Offay. He had already lost one relationship to his art career, and he didn’t want to sacrifice another. In Dallas, Patterson could have a large studio. He and Rees could buy a little house, maybe have children. And they could keep a few exquisitely crafted British sports cars in the driveway.

“I was seduced by the American dream,” he says.

But Dallas is a city of more than space and dreams, and soon after he arrived, he began to understand the place where he had landed. The first difficulty was the climate, how oil paint behaved differently in the Texas heat and humidity than it did in London.

“Climate seems a small thing, but the climate could be so hostile,” he says. “And it was speeding up the way the solvent evaporates out of the paint. The oil starts to cure very quickly. Because of that, you are always working against time, and that is hugely stressful.”

In an odd twist, Patterson had attempted to leave behind the breakneck pace of the art world, but time had only become a greater pressure. Just before he’d moved to Dallas, Patterson had signed with a new London gallery, Timothy Taylor, whose namesake had worked with Leslie Waddington. Patterson hired assistants, found a big studio, and tried to speed up his painting process. But it all only ended up slowing him down.

“I just wasn’t making enough work to supply both galleries,” he says.

In addition to struggling with his painting process, culture shock hit him hard. In London, he says, if you’ve shown a bit as an artist, you naturally get swept up in a self-propelling art circuit: dinner parties, exhibition openings, and museum functions attended by other artists, dealers, curators, and collectors. In Dallas, Patterson encountered a scene in which curators, artists, dealers, and collectors from out of town were whisked to museums straight from the airport before a cocktail with collectors and a chaperone back out of town.

“It took me a while to realize there was a pay-to-play culture in Dallas,” he says. “I used to joke that [Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth chief curator] Michael Auping has a private underground passage that took him by hover boat all the way to New York.”

Patterson’s feeling of ostracization wasn’t helped any by his natural candor, a British mixture of self-deprecating humor and satirical wit that takes a knavish delight in poking at social taboos. Dallas society, by contrast, prizes politeness and boosterism. Right off the bat, an auction snafu between Dallas collector Howard Rachofsky and James Cohen over the sale of one of Patterson’s paintings made his relationship with the cliquish Dallas collector community awkward. Then came the period Patterson refers to as his “save Dallas phase.” Rees opened Road Agent gallery in 2006, and Patterson became absorbed in the planning—architectural sketches, real estate, parking codes. Thinking about how to locate and operate a gallery in Dallas got Patterson thinking about how Dallas functions as a city and how it supports its culture.

He began writing emails that ripped into Dallas politics, culture, economics, urbanism, architecture, food, and, of course, cars. He railed against Dallas collectors and patrons, chastising what he saw as their self-serving philanthropy. He criticized Dallas galleries for not helping artists’ careers. He often referred to the Dallas Effect, his postulation that anything that belatedly arrives in Dallas (like an art fair) does so at precisely the moment it is no longer an interesting idea everywhere else.

“The entire patron class operates in this way,” he says. “Don’t ask questions, or the whole thing may collapse like a house of cards. Just be grateful that we have a museum at all.”

A collector once asked him if he ever started a sentence that didn’t begin with “The problem with Dallas is …”

Patterson responded: “The problem with Dallas collectors is …”

If Dallas’ patron class didn’t embrace the British artist upon his arrival, things got less friendly as time went on. And then they got surreal. Kenny Goss opened his British-themed art space in 2007, and now a city Patterson already saw as a crass conglomeration of facsimiles, false pretensions, and superficial consumerism had an art center dedicated to the very art movement he had helped create.

“Then there’s actually a center of YBA where they sell mugs with Union Jacks on them,” he says. “It’s just so unbelievable. I mean, the ludicrousness of it all.” Patterson admits that dealing with the stress of keeping up his artistic practice and adjusting to Dallas’ peculiar culture made him a bit manic. “I mean, you go to these parties, and Kenny gives you these massive vodka tonics, and everyone is blind drunk. I was probably losing my mind. I had become a bit of a crazy person. I felt like a movie actor stuck in a bad sitcom job, but Dallas is the sitcom.”

When he first moved to Dallas, his New York dealer, James Cohen, told him he was making a big mistake, but Patterson ignored him. He was tired of listening to dealers and making decisions based on his career. “I wanted to see what it is like to be an artist who is not on the life support system that the art world actually is, what happens when you unplug yourself from it,” he says. “I realize that you die. That’s what actually happens.”

•••

“I wanted to see what it is like to be an artist who is not on the life support system that the art world actually is, what happens when you unplug yourself from it. I realize that you die.”

When Patterson finally finished his re-creation of Motocrosser II in 2011, he realized that he hadn’t re-created his painting at all. There was something about the terrible process—the belabored effort, the humidity of Dallas, the way he had changed as a painter in the 15 years since he’d originally made the work—that felt ineffably present in the rendering of the image. This was a new work of art, and so it needed a new name. Patterson called it Your Own Personal Jesus.

With that nightmare project behind him, he suddenly found himself free. The unfinished pieces he had started before taking up Your Own Personal Jesus no longer appealed to him. He needed to make something that felt immediate, that flowed freely, that spoke with a new voice. It was around this time that Jan van Toojerstraap was born in an email drafted by Patterson and sent to friends, including Jeremy Strick, director of the Nasher Sculpture Center.

Strick had arrived from Los Angeles to head the Nasher in 2009, and he began to make the kinds of connections that Patterson had for years said Dallas needed: inviting artists to museum dinners, forging friendships with the patron class and artists working in the local scene. The two became friends, and Patterson served on the Nasher’s program advisory council. Strick’s inbox was a safe space for Patterson to let loose.

If any of Patterson’s friends thought the artist had cracked, Toojerstraap looked like the last straw—a half-witted, sex-crazed Dutchman who sends impossibly long emails written in such terrible, broken English that some are hardly readable. In the very first of these emails, Toojerstraap introduced himself as a Dutch national temporarily relocating to Dallas. “I hoping it will be a great place for plenty of experimentation with soft drugs and really hard core porn,” Toojerstraap wrote. “Like we have in the really leading liberals Dutch schools.”

Toojerstraap was set up for disappointment. What he instead discovered was a city that escapes the capacity of his warped Continental sensibilities. Through his eyes, Dallas takes the form of an absurdist porno Candy Land, filled with sex parties and societal faux pas, populated with caricatures that feel part Terry Gilliam, part Fred Armisen, part Sacha Baron Cohen.

“Here was a really fantastic Gesamtkunstwerk with the really great motorbike for having three-way rides on in the traditioning of Wagner and Anselm Keifffer,” Toojerstraap wrote about visiting the Goss-Michael Foundation. “But the ladies with plastic boobies who keep them for the whole time in the dresses, just put their drinks on the really great art sculpture by Patterson Patterson because they think its a table or a ploojer bed or somethink funky.”

The character emerged at a particularly low point for Patterson. He was incensed by an incident at a Goss-Michael opening where drunk Dallas society types left their wine glasses on Patterson’s sculpture and one woman stepped on Sarah Lucas’ neon coffin, breaking it. Toojerstraap was a knee-jerk reaction to the philistinism that Patterson witnessed.

“At this point, I had seen all this terrible stuff going on,” Patterson says. “And Toojerstraap spontaneously came to me that the only way of expressing this extreme frustration was with some sort of innocent-sounding guy.”

Not long after Toojerstraap’s birth, Patterson’s painting began to lash out with new freshness. The way forward was offered by a work of art Patterson had completed in 2009 called Portrait of the Artist as an Older Man. It is a mash-up of disembodied breasts and scaled-up smears of abstract paint framing a slightly scowling face stolen from a work by the Italian Renaissance master Giovanni Bellini. His new work continued this bridging of abstraction and photorealism, and possessed an energy that fed off the delight Patterson was taking from indulging in the sensuality of his paint. He also made some works under Toojerstraap’s name, using the alter ego as an excuse to branch out into text-based work and conceptual art. He created a video montage attributed to a second alter ego, Marianne Leflange, with footage mined off YouTube that reads like a 30-minute litany of his most personal influences, juxtaposing Jacques Tati slapstick, motocross racing, a Milan Kundera interview, Russ Meyer breast films, and an English boys choir singing in a gothic cathedral.

Through Toojerstraap, Patterson began to find a way for the social criticism he’d expressed for years in his emails to work its way into his paintings. He sought to push back against cultural politeness, not just in Dallas but in the larger culture. He wanted to attack the self-policing and conservatism that are written implicitly into the rules of the art world, to paint for the sake of painting.

“If that is the prevalent culture, you can’t be Picasso anymore,” Patterson says of the political correctness of the market-obsessed art world. “Look at late Picasso. It is supreme objectification for the sake of a pure painting opportunity. I didn’t want to make art that was satirical. I wanted to tap this expressionistic style, like a proper German expressionist, in a politically dangerous way.”

A review in the London newspaper the Independent of a 2013 career survey exhibition at Timothy Taylor Gallery affirmed his new direction and placed it in the continuity of his broader career. “While many of the YBA generation have churned out nihilistic bric-a-brac and snidely humorous kitsch, these paintings are alive,” the critic wrote.

•••

“British racing green Jaguar XJS 1994–2014. It will be survived by its owner, Sir Richard Patterson, Lady Christina Rees, Trixie Rees-Patterson, Murray Rees-Patterson, and Wallace Rees-Patterson,” he wrote, referring to his wife, dogs, and cat. “To the last I could smell the Coventry factory floor. The lathes’ white cutting fluid, polished aluminum, the hat swarf, the tanned hides from the trimming shop where various pale factory workers and shop fitters with slightly crooked teeth set about expertly grooming the car to go forth into the world with purpose, poise, and restraint.”

Patterson concluded that the only way forward was to purchase a new Jaguar F Type Coupe, but now an upcoming exhibition at Timothy Taylor Gallery that November had a new, ulterior purpose. Without his Jaguar, he was stuck driving a tiny, gray Fiat rental in Dallas. When he traveled to England, he would go to Lincolnshire in northeast England to check on his 1969 Porsche 912 Coupe, which was undergoing extensive restoration at the world-famous Gantspeed Engineering. The car was his steed during his last years living in London, and he was considering bringing it back to Dallas.

Patterson thinks the trip to Gantspeed could be an important scene for this story, which is how I wind up making the trip to London for the gallery show. I’m curious to see the city through his eyes.

Even though it has been 10 years since Patterson has lived here, upon arrival I am immediately swept up into his scene. We lunch at Scott’s, a restaurant where Patterson bumped into Damien Hirst the day before. We drink Champagne and eat raw oysters and smoked haddock. Patterson walks me around Mayfair, takes me to Waddington’s gallery, and poses in front of a storefront Jaguar dealership just off Berkeley Square.

“See? You don’t need a giant concrete parking lot to have a car dealership,” he says.

We end up drinking pints in the street in front of the Guinea Grill, a 600-year-old pub, with a crowd that includes young men in suits straight off of work standing shoulder to shoulder with construction workers from a nearby work site. Patterson is quick to note how un-Dallas this blending of blue and white collars is.

Later that night, the exhibition is crowded. I see Michael Craig-Martin and meet Richard’s brother Simon, who jokes that his parents were a little worried when two of their four boys decided to pursue careers as artists.

The exhibition is risky for Patterson. Not only does it include prints of his large-scale photorealist works, but there are also new abstract paintings and Leflange’s video. Many of the paintings depict Rees framed by abstract paint. “Lots of Christina,” a London dealer says when I ask for his take. In fact, Patterson created too much work for the show, and the gallery decided not to include an encouraging new series of works, abstract-y portraits of figures that are then photographed and blown up as prints. He identifies the figures as relatives of Jan van Toojerstraap’s.

Toward the end of the opening, the actor Adrien Brody strolls in. It turns out Brody is a friend of one of Patterson’s collectors, and he will be joining us at dinner after the show, which is being hosted by Timothy Taylor’s wife, Lady Helen Windsor Taylor, a member of the British royal family who stands 38th in line for the throne. I think for a moment about a typical Dallas art opening and wonder if all of Patterson’s criticisms are just a little, well, unfair. Dallas will never be London. Later, I ask Patterson what it is like to come to London these days as the guy from Dallas.

“There is a Catch-22,” he says. “In order to be respected as an artist, you have to be respected in the city you function in. But Dallas is a city that can’t do that. It looks to New York for that validation. So when I show in London, I’m this artist from Dallas who is not respected in Dallas.”

The next morning, Patterson heads to Gantspeed to check on his Porsche. I receive an email with an attached photo of a windmill. “We drove past this windmill on the way through Boston—it seems to be quite well known—the Maud Foster windmill,” he writes. “Possibly Jan’s birthplace, although mysteriously, I didn’t see a blue plaque on the side of it to commemorate Jan, as is normal. Maybe because Jan is still alive.”

Back in Dallas, I’m past deadline on the story, and Patterson is still sending emails, pages of diatribes from Toojerstraap, collections of his favorite things he’s said over the years, and background on his various cars and motorcycles. He is still concerned about the shape the story will take.

“I have this feeling that Tim [Rogers, D Magazine’s editor] thinks that I’ll go buy the new Jag and that’s the end of the story,” he says. “I’ll have this ugly duckling who comes out thing. But this is just where I happen to be in this moment at this time.”

At this moment, Patterson isn’t an emergent duckling. He is living in Dallas much like he has for the past 10 years, quietly making art and occasionally popping up at openings and landing in someone’s inbox. He is right that the story shouldn’t end by concocting some false re-emergence from his exile into the limelight of the international art scene. Still, I can’t shake the idea that this moment feels like precisely the right time for Patterson to get out of Dallas. His career has stabilized, he is still selling paintings quickly, and he has started a number of promising new bodies of work.

Late one night in his study after we get back from London, I ask him if he is ready to return. He tells me he feels like he needs to “paint my way back to London,” but later admits that the move is more contingent on his relationship with Rees. “We could just move back to London now,” he says. “But sometimes I want to leave, and it doesn’t work for Christina. While sometimes she wants to leave, and it doesn’t work for me. But it’s okay, because what’s good for her is good for me.”

It strikes me that if Patterson really is, as he says, Calvino’s cloven viscount—the man split in two, whose best half is ignored—then the only way to end this story is to write about that half. In the hundreds of pages of emails I’ve received from him over the years, in the tens of thousands of words, amidst all of the stories about how he used to bring women to orgasm just by racing them around London on the back of his Triumph and tales about his great-great-great uncle Ned, who was the last survivor of the Charge of the Light Brigade (which is true), and the invented fantasies of Jan van Toojerstraap, never once has Patterson mentioned that in his quiet life in Dallas, he cooks ground chicken and basmati rice with parsley purchased at Whole Foods nearly every night for his Royal Musky Terrier (a breed of his own invention) Murray, whose name is tattooed on his wife’s forearm. Not once has he written about how he is such an attentive, caring parent to these animals that he ground up Viagra and put it in his dog Trixie’s food when she was dying because the drug is believed to improve heart circulation and quality of life. Someone else, a friend of his, told me about all that.

He probably wouldn’t want me to write about how, in the hours before his London opening, he and Rees called their pet boarder from the basement of Timothy Taylor to check on their animals. When they discovered that their cat Wallace had isolated himself and was refusing to eat, they were so worried about the little creature that they considered cutting their trip short to fly home.

If Richard Patterson had told this story, he wouldn’t have included these little bits, because he knows that creating iconography and myth—the collateral of his artistic process—is as much an act of omission as it is inclusion. Kindness shown to the animals and people in your life is not a quality we associate with the figure of the heroic, daredevil racer. But that’s where I believe we have to end the story, because Patterson’s art, for all its virtuosity, appetite, and ambition, is itself an act of exploring the limitations implicit in the silliness of human desire. And for all its flirtation with the lofty heights of success, Patterson’s career has been a measuring out of limitation.

He knows now that you can’t really remake a painting of a motorcycle racer that was burned up in a fire. You can’t remake the culture of the city in which you live. But you can cook dinner for your dogs, and you can make a home for them with your wife. That’s the real painstaking labor of life, a work that is the product of continual making and remaking.

And you can do it wherever you happen to live, even in Dallas.