As I lugged my bike up the side of the Trinity levee, tired and out of breath, I couldn’t help but wonder if it was really necessary for our levees to be so very, very tall. This was in the spring of 2006. After struggling to the top, I joined my husband, Paul, to ride along the gravel road that stretched the length of the embankment. Below us, the Trinity River basin was green and lush and vast.

Elected to the Dallas City Council less than a year earlier, I had spent 10 months digging into the details of major city projects. Now I had turned my attention to the Trinity River. Paul and I had spent weekends bicycling inside the levees. Between us, we had lost three bicycle tires in as many weeks to spiky burrs and sharp gravel. Where were the concrete trails? It had been nearly a decade since voters had approved the massive Trinity River Corridor Project, which had included long ribbons of bikeways and running paths. So why hadn’t the city-—or the various nonprofits devoted to shepherding this project—laid miles of trails by now?

Not long after our bike ride, as I dug deeper into the Trinity Project, I discovered that the Trinity Parkway (which had been described to me by city management as an innocuous, meandering road) was actually a massive highway that would destroy the park. I learned that the park was just window dressing; that the city’s primary focus was the road; that there was no real interest in bringing life between the levees, only cars. Within six months, I had organized a referendum to kill the toll road. We lost. The park continued to languish.

In 2012, the city’s $600 million bond program presented an opportunity to fund trails along the Trinity. But despite years of throwing extravagant Trinity fêtes and crowing about the unparalleled promise of the Trinity, the city refused to include the trails in the bond initiative. And the Trinity nonprofits were too busy raising money for Calatrava bridges and advocating for the Trinity toll road to be bothered to dig into their couch cushions for pedestrian trails.

So I was delighted to learn that each council member would get $2.8 million in bond funds to allocate to projects of his or her choosing. Scott Griggs and I pooled our money to fund the Trinity trails. We spent the next year battling city staff and several council members who sought to block construction of the trails, ostensibly because of “safety concerns.” But within two years, the concrete was poured. The 5.6-mile Trinity Skyline Trail officially opened last summer.

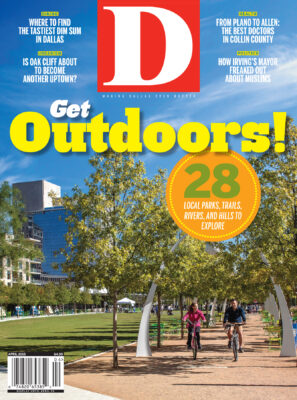

A few months later, I sat with Paul and our two girls on a picnic blanket under an old train bridge near the Trinity River. Bicycles glided past us on a winding concrete path that followed the banks of the Trinity River from Commerce Street to the Sylvan Bridge. The trail teemed with life, and its popularity will only grow when it more than doubles in length. Over the next five years, the city of Dallas and the federal government will invest $7.6 million in a 6.2-mile extension connecting the Trinity Skyline Trail east to Irving’s bikeways and west to the Santa Fe Trestle.

Despite the conspicuous absence of solar-powered water taxis, on that day at least, people seemed to be enjoying themselves.