One day in 1997, I stood on the corner of McKinney and Allen streets with Robert Shaw, an apartment developer. We were surveying an area that he and a like-minded group of urban pioneers had just named Uptown. Shaw had put his money into constructing three apartment buildings, and at the time, he was begging other real estate developers to jump in. They were hesitant. Shaw had established stricter codes for the area taken from the writings of urbanist Jane Jacobs. For example, no setbacks were allowed for buildings. They had to butt up to the sidewalk, because residents should be able to step from their front door onto the street.

In Dallas at the time, such things were unheard of. Developers only built suburban “garden” apartments, where there were rarely any gardens. But Shaw stuck to his guns, and soon his buildings filled up. Developers noted his occupancy rate and decided to join. At the time, there were few restaurants, bars, and retailers. “If we could just get to 5,000 people,” Shaw moaned that day. “The place would light up.”

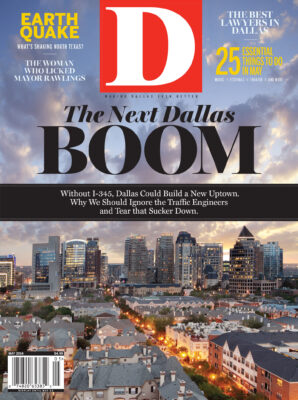

Today, Uptown has about 25,000 residents and some 20,000 people work there. I live in a small condo building a block from where Shaw and I stood. I have eight restaurants to choose from within two blocks, and Whole Foods is going in three blocks away. The place is now well lit, and on Saturday nights, that’s in both senses of the word.

Dallas is not really a city, not in the traditional sense. It is a collection of suburban-like neighborhoods with a downtown. All of us who grew up here—developers included—were raised with the suburban model. It was all we knew. Shaw broke that mindset. He built what in any city would be just another development, but in Dallas was heresy.

Shaw and his friends had to fight every inch of the way to get what they wanted. City Hall didn’t like the narrow streets (“Where will the traffic go?”), the density (“Where will people park?”), or the strict rules Shaw intended to impose. Shaw is a persistent man, and he finally won them over. (After all, he and his group were the only developers willing to invest in Dallas in one of its darker moments.)

What Shaw saw—and the naysayers did not—was that the world was changing. Dallas was built in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s for married couples with children. Today those couples compose only one-fifth of households—and many of them have decamped to the suburbs. If you want to live in Dallas, you are largely stuck with the housing stock of decades past: a house with a yard, an alley, and a driveway. The only way to get anywhere—a restaurant, the dry cleaner—is by car. Unless you can live in Uptown.

But few people can afford to live in Uptown. There is too much demand and too little space. As a result, Uptown is now one of the most expensive places to live in the state.

Uptown was a fluke, a dilapidated and almost empty neighborhood that nobody wanted, leaving no competition for a gutsy group of people willing to invest in a new model of living. That will not happen again. Next time, it will have to be a conscious decision by a city determined to grab a market that is waiting to be served—the hundreds of thousands of people in North Texas who want to live in a real city.

That’s what the recent contretemps over Interstate 345 is really about. The highway runs smack-dab through some of the most potentially valuable real estate in the city, land that could connect downtown and the Farmers Market with Deep Ellum and Baylor University Medical Center. To replace that elevated interstate with an urban parkway would allow that area to be transformed into a new Uptown, with mixed development, retail, and entertainment options for residents. Boom! Another dilapidated area revived, an increased tax base, and more options for city dwellers.

But in February, the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) announced that it would repair the highway so that it could stand for another 20 years. They said they hadn’t considered other options. At first, it seemed City Hall would meekly acquiesce.

But the business and real estate communities immediately raised the alarm. Does City Hall even grasp what just happened? Or what is at stake? Do they realize there is potentially $4 billion in taxable land value under and around that highway?

It’s a simple rule of economics. When demand for a product is high, make more of it. When people want to move to your city, you do whatever you can to invite them in. The land under and around I-345 is one of the very few places in the entire city where there is enough acreage to create the critical mass of residents and services that an urban environment requires.

TxDOT says it needs to repair the bridge at a cost over time of $100 million. It also says tearing down the highway and restitching a slower road with the neighborhood fabric would cost $1.9 billion and take 10 years to “study.” County Judge Clay Jenkins wants a condensed study done before repairs begin in 2015, fearing that once TxDOT starts, a teardown will go so far onto the back burner that it is never heard from again. His interest is in the estimated 22,000 jobs redevelopment would bring, mostly for people in the southern sector.

This battle is not just about I-345. It is about a strategy. It is about duplicating as many times as we can the one success urban Dallas has—Uptown. It is about a city devoted more to residents than to commuters. Tearing down the aged hulk of I-345 is a first, small step. But it could be enough to tell the market that Dallas is finally about to assert itself as a real, honest-to-God city.