Anyone who was a kid in the early ’60s remembers the opening of Six Flags Over Texas in Arlington. The 212-acre amusement park, built by local real estate developer Angus G. Wynne Jr. and opened on August 5, 1961, changed the way Dallas played. Families, dates, and packs of kids roamed the streets that wove through six distinctive entertainment sections: Spain, France, The Confederacy, Texas, United States, and Mexico.

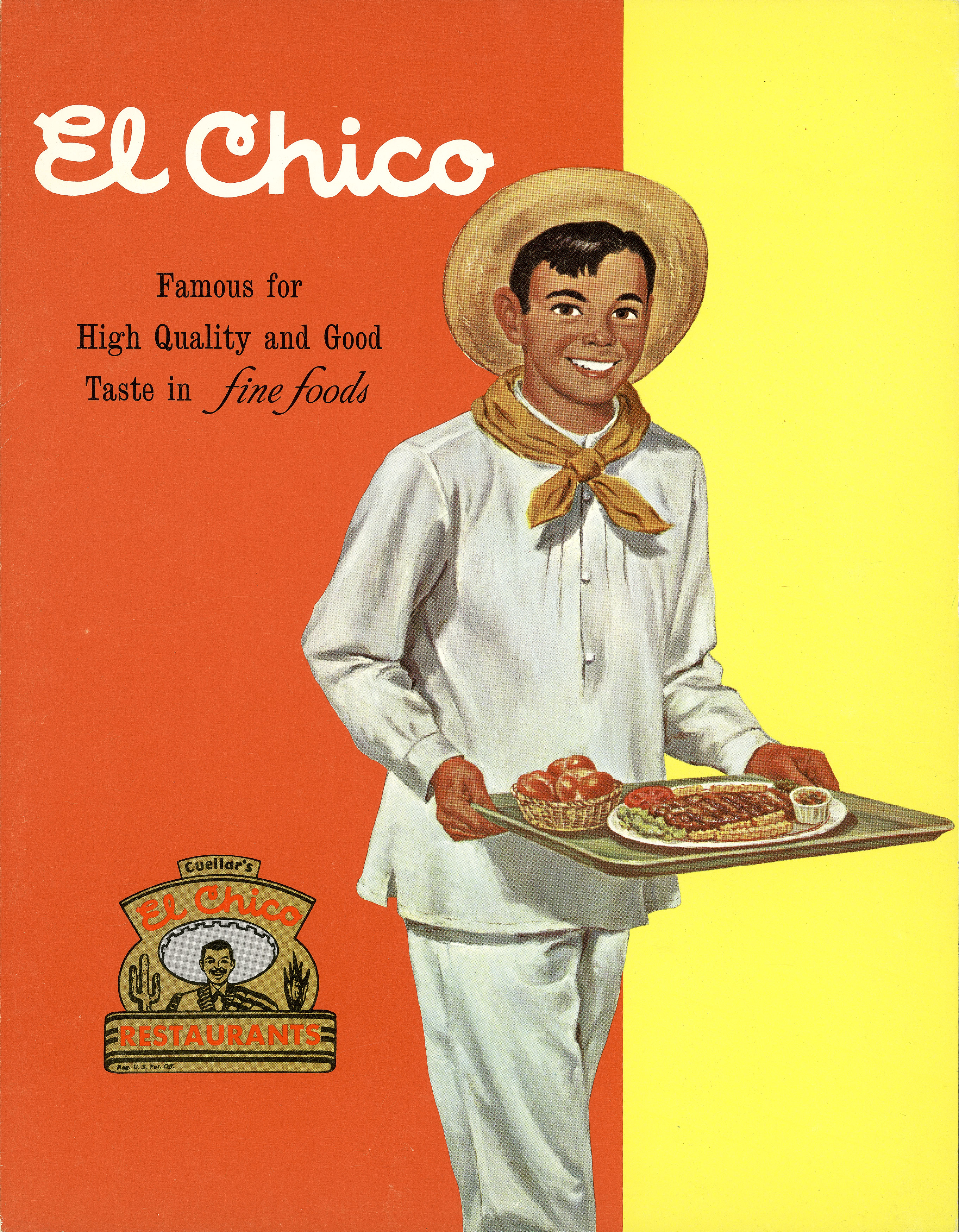

It wasn’t hard to find Mexico. The aroma of Mexican food filled the air. All you had to do was take a right at the goat cart ride and follow your nose. It took you right to El Chico, the 11th restaurant opened by the Cuellar family.

People came from all over the world to frolic at Six Flags, and many of them ended up in the buffet line at El Chico. Most had never seen Mexican food before and were wary to try it. Even locals had to be seduced into sampling Tex-Mex items with hard-to-pronounce names. Tacos (tack-os) and enchiladas (en-chill-lay-dos) were not served in restaurants that catered to Anglos. And the appearance of that green goopy stuff—guack-amole—was off-putting to snooty diners.

To capture their curiosity, El Chico, and most other emerging Mexican joints, featured American-friendly chicken-fried steak and fried chicken to lure gringos to the table. Cleverly, instead of a handful of fries or a baked potato, they slipped a tamale or a taco onto the plate. For the more adventurous set, El Chico filled its menu with large photographs of their combination plates, so diners could get a visual of what they were ordering.

She used the money to open Cuellar’s Cafe and put her kids to work. Once the depression hit, the restaurant closed, and the oldest five boys—Frank Sr., Mack, Alfred, Gilbert, and Willie Jack—left home and settled in Shreveport, Tulsa, Dallas, and Oklahoma City. All of them opened restaurants.

In 1940, Mack, Alfred, Gilbert, and Willie moved to Dallas and, with a $500 loan from Mama, opened the first El Chico on Oak Lawn near Lemmon Avenue. Frank Sr. joined his brothers in 1949, and the five entrepreneurs decided to pool their talents and create the El Chico chain. By 1950, “Mama’s Boys,” as they were known in Dallas, were operating five restaurants. This was an incredible achievement. They weren’t using a model or a franchising formula. The major force behind their expansion was to provide good jobs to the people in their large family. For comparison’s sake, in 1955, McDonald’s was still a small hamburger joint in Southern California.

In 1962, business for Mama’s Boys was booming. Tacos, enchiladas, and chili were on the menu at 11 El Chico restaurants. Number 11, the Six Flags location, had the highest sales volume, and it was open only seven months out of the year. The Cuellars also owned El Chico Commissary, a successful business that produced canned and frozen El Chico products for distribution in grocery stores in 22 states. Gross sales were more than $2.5 million. In 1962, El Chico Commissary Inc. and El Chico Foods Inc. merged to form El Chico Corp., a food business with sales topping $5 million a year and paying out $1 million in payroll.

A year later, in 1963, El Chico had its busiest year: restaurants opened in Waco, Austin, Shreveport, and Tyler. Soon after, the company made its national debut.

The Texas Pavilion was a colossal failure. Wynne came back to Texas and filed for bankruptcy. To celebrate, he and his wife, Joanne, threw a bankruptcy party at their Highland Park home. The host dressed in raggedy clothes, and guests went through a soup-line buffet. The Cuellars returned to Dallas, entertained John Wayne at one of their restaurants, and hung out with their friend, world-famous musician and Dallasite Trini Lopez.

When Princess Grace of Monaco decided to throw a series of internationally themed parties, she called her friend Lopez and asked whom she should call in Mexico to cook for her. Lopez told her the best Mexican food wasn’t in Mexico; it was at El Chico in Dallas. In July 1966, Willie Jack and Claude (the son of Jim, the only brother who didn’t get involved in El Chico), loaded a plane full of ingredients and flew to Monaco where they cooked and served dinner for Prince Rainier, Princess Grace, and their guests.

In 1968, the company went public with a 172,000-share offering of its common stock. Mama’s Boys were millionaires, a feat witnessed by the woman who started it all. Adelaida died at the age of 97 a year later. By 1970, El Chico was operating 44 restaurants.

Across town, Norman Brinker was just getting started. He opened his first Steak and Ale in 1966 and sold more than 100 of them to Pillsbury in 1976, remaining with the company. Dallas restaurateur Larry Lavine debuted Chili’s, the comfy burger joint with a few Tex-Mex items, on Greenville Avenue at Meadow Road in 1975. Customers waited in line for the beer served in frosty mugs and their soft tacos filled with chili. Within eight years, Lavine operated 23 restaurants scattered across six states. Chili’s got Norman Brinker’s attention: he left Pillsbury and bought Chili’s in 1983, taking it national. Gene Street opened his first Black-eyed Pea in 1975 and sold the 130 locations in 1986 for $47 million.

The success of Dallas restaurant entrepreneurs didn’t go unnoticed. The city’s reputation for creating, testing, and rolling out successful chain restaurants attracted large companies such as Pizza Hut, Carlson Worldwide Restaurants, and Pizza Inn. “If you can make it in Dallas, you can make it anywhere” was uttered in boardrooms across the country.

Since 1968, El Chico has seen six changes of control. The last occurred in 1998 when Dallas restaurateur Gene Street, then CEO of Consolidated Restaurants Operations, bought the stock. El Chico now operates under the CRO umbrella, and Carmen Cuellar Summers is the last family member on the El Chico payroll.

A few months ago, John, Susan, and Gilbert Cuellar, son of Gilbert Sr., met over a long lunch of chicken enchiladas topped with mole sauce and chipotle chicken quesadillas. I listened as the two recited the history of their family and the values embedded in their DNA. Regular customers stopped by the table to pay tribute. Both brothers beamed with pride. Gilbert and John are still living the family’s dream.

Gilbert talks fondly of his grandfather who “always encouraged his children to push hard and don’t go slow.” He remembers how Adelaida taught her children to be honest. “When most of the other workers quit for the day, they just kept on working,” Gilbert says. “Having 12 children is a great incentive to work. Especially since they wanted the best for them.”

It worked. For their children, their grandchildren, and their city.

“Dallas has always been a city that rewards ambition and doesn’t punish failure,” John says. “It didn’t matter where they came from. They were entrepreneurs and worked hard, and they were always accepted. Angus Wynne Jr. saw we were ambitious, and he gave us a chance. He gambled, and Mama’s Boys delivered.”