Bonnie Simons is a friendly, outgoing woman with a slim build and a youthful exuberance. You might never guess that just over a year ago, the 5-foot, 8-inch bank executive weighed 330 pounds and was losing her husband of nearly 25 years to cancer.

Simons’ struggle with her weight began early. She recalls dieting even as a child. When she put on a few pounds during puberty, she didn’t think much of it and dismissed it as a growth spurt. In college, while her peers gained the typical 15 pounds, Simons gained 75. After college, she married her husband Aaron, pursued a career, and traveled the globe. But despite trying a number of diets, Simons’ weight continued to climb.

In the late 1990s, Simons was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes. For more than a decade she was able to control the disease with medication, but eventually its effectiveness wore off. Simons’ doctor started her on insulin, but the daily injection caused her to feel hungry. She was trapped in a cycle.

Then in July 2006, Simons’ husband was diagnosed with colorectal cancer. To cope with the devastating news, Simons again turned to food. “In some ways it was my drugs or alcohol,” she says.

It wasn’t until the year following her husband’s diagnosis that Simons first considered weight-loss surgery. By that time, her weight was hovering around 295 pounds.

“I thought surgery was the easy way out or cheating somehow,” she says. “It’s not true, but it’s what I thought at the time.”

Simons attended a seminar presented by Dr. Stephen Hamn, general surgeon at the Texas Center for Obesity and General Surgery and a physician on staff at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Plano. But the timing wasn’t right.

“I was busy at work. My husband and I were going to Greece. I thought I could still [lose weight] without surgery,” Simons says.

It’s not easy for patients to take that first step, says Hamn, who helped Presbyterian Plano earn Center of Excellence certification from the American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. “The hardest part I see is getting patients to call and come in,” he says. “It’s an emotional decision for them.”

Not a Quick Fix

Although weight-loss surgery has been around for decades, it has only been within the past several years that the surgery has become more widely accepted. Stigma long associated with the surgery kept many patients away.

According to Hamn, the idea that surgery is a quick fix is a common misconception. “The theoretical idea of ‘I want to be thin’ is easy,” he says, “but the actual practice of that is really tough.

Dr. Nick Nicholson, medical director of weight-loss surgery at Baylor Regional Medical Center at Plano and Forest Park Medical Center, concurs.

“It’s a lot of work. It’s keeping [weight loss] at the forefront of your mind. You have to continuously make choices that lead directly to your success or your failure,” he says. “This is a lifelong process.”

It is a lifestyle change that could affect millions of Americans, thousands in North Texas. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), estimates that about 97 million adults in the United States are overweight or obese. Fewer than one-third of U.S. adults are considered to be a healthy weight.

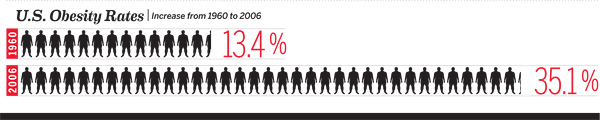

And obesity rates continue to go up. According to a recent study by the NIDDK, instances of obesity in U.S. adults increased from 13.4 percent to 35.1 percent between 1960 and 2006. That means there’s growing potential for weight-loss surgery patients. Add to that increasingly lower qualifications for surgery, and you have a booming industry.

New Techniques, Procedures

Today most weight-loss procedures are done laparoscopically—much less-invasive than the open surgeries of the past. Collin County patients gravitate toward three procedures: the adjustable gastric band, the gastric bypass, and the gastric sleeve.

Gastric banding is a procedure in which a small band is placed around the top of the stomach to restrict the size of the opening to the stomach. Within that band is a balloon that can be inflated or deflated with a saline solution to correspond with the changing needs of the patient.

In gastric bypass, the small intestine is stitched directly to the base of the throat, which restricts food intake and changes the way the body digests and absorbs food. In this procedure, the stomach, duodenum, and upper intestine no longer have contact with food.

Through the gastric sleeve procedure, most of the stomach is removed, severely restricting food intake. Because of the stomach’s removal, the body’s secretion of ghrelin, a hormone that controls appetite, is also decreased, which causes a patient to feel hungry less often.

Demand within the three most popular procedures has recently been shifting. For example, for years, 60 percent of the procedures performed in Nicholson’s office were gastric bypass, 40 percent gastric banding. But within the past five years that has changed to 60 percent gastric sleeve procedures, 30 percent gastric bypass, and 10 percent gastric banding.

Beyond typical surgery risks—bleeding, infections, blood clots, or injury to organs—complications unique to weight-loss surgery can also include poor nutrient absorption, narrowing of the sites where the intestines are joined, or hernias. The risk of death has dropped dramatically over the years; it now stands at fewer than 1 in 1,000.

And it turns out that the condition of obesity is riskier, according to a 1991 National Institute for Health consensus panel. “Overweight people die early,” says Nicholson. “A 40-year-old with a BMI of 40 is going to die 22 percent earlier than his 40-year-old counterpart with a low BMI.”

Costs can vary widely—anywhere from less than $10,000 to more than $40,000. But many weight-loss procedures are covered by insurance. According to a study by HealthGrades Inc., commercial insurance pays for about 74 percent of weight-loss surgeries. Government insurance, like Medicare, pays for more than 20 percent. But insurance coverage may come with hard-to-meet stipulations.

“Only about 1 percent of people who qualify actually have the procedure, often because of insurance companies,” says Hamn, who estimates that 5 percent of his patients are self-pay clients. “Insurance companies restrict access to care or make people jump through hoops [to get the surgeries covered].”

DFW a Top Weight-Loss Surgery Market

Despite the red tape, North Texas patients are increasingly opting for surgery. “I think it’s becoming more acceptable. “It’s one of the top weight-loss surgery centers in the country,” Nicholson says. “There’s a lot of surgery that goes on here; it’s also one of the areas with the highest number of overweight people.”

According to the HealthGrades study, Texas is one of the top states for bariatric surgeries, with more than 23,000 weight-loss procedures performed from 2007 to 2009. More often than not, the number of female patients surpasses the number of male patients. Nicholson estimates that 70 to 80 percent of his patients are women. And, although he has operated on patients as young as 16 and as old as 80, his average patient is 40 years old.

“I do think that weight-loss surgery should be a last resort,” says Nicholson. “The average patient has contemplated surgery for two years. They’ve failed a minimum of 10 diets in their lifetime. They have struggled with the decision, but once you reach the criteria for being morbidly obese, diet and exercise alone has a 98 percent failure rate.”

Bonnie’s Choice

By the time Simons decided it was the right time for her to pursue surgery, her husband had been battling cancer for nearly three years. She was overwhelmed by the stress of balancing day-to-day responsibilities while also taking care of an ill spouse, and her weight reached its highest ever: 330 pounds. By 2010, she had begun to see surgery as a tool to empower her, rather than the easy way out. With her husband’s support, she went back to Hamn’s office to explore her surgical options. Initially set to have the gastric band, she reconsidered after learning her insurance would pay for gastric sleeve.

“With the sleeve, they take out about 2/3 of your stomach,” says Simons. “I don’t feel as hungry, and that is what has helped me reach my goal.”

To prepare for surgery, Simons underwent three months of preliminary procedures, including seeing both a nutritionist and a psychologist, submitting to necessary tests, and lowering her blood pressure and diabetes enough to withstand surgery. Her surgery was scheduled for May 4, 2010.

But in late April, Simons’ husband began experiencing cancer-related complications and was unexpectedly admitted to the hospital. While he awaited his own surgery, he and Simons decided she should forward with hers.

Aaron Simons never left the hospital. He died on June 10, about one month after his wife successfully completed her surgery.

Learning to cope with the loss of her husband in new ways—ways that did not include food—was difficult. Simons faced many emotional peaks and valleys, but she kept telling herself to “trust the process,” even in face of plateaus.

Today Simons has lost more than half her body weight—180 pounds total. She is off two of the three medications she was previously on, and her blood sugar has returned to normal. Her doctor is very pleased.

“It’s the second-best decision I’ve made in my life—the first was marrying my husband,” Simons says. “It has worked so well, and it was so successful for me that I wish I’d done it sooner.”

Although there’s no set formula for what happens after surgery, it takes an entire team to make weight loss successful. Reputable surgical practices offer resources to patients who need support in changing their lifestyle—resources including nutritionists, psychologists, cardiologists, and trainers.

“Being overweight is a series of bad behaviors, not bad people,” says Hamn. “Having the surgery helps overcome some of those bad behaviors, so if we can eliminate some of the trigger points, then we’ll be successful.”

The responsibility for long-term success, which he considers at least five years of sustained weight loss, lies with the patient, he says.

“The operations have differing degrees of risks and success,” Hamn says. “I give [patients] a tool and directions on how to use it. If they do well or don’t do well, they get all the credit for that.”

By all accounts, Simons has done well. She has more energy than she used to. She works out with a trainer—something she never did before. She even travels without feeling anxious about what the person sitting next to her might think.

Simons has seen both sides of the weight-loss coin. “When you’re overweight, everything is exercise,” she says. “I also think that there are misconceptions about overweight people in this country. We are very sensitive about people who are different from us, but when it comes to weight, it’s the last acceptable form of discrimination.”

Adjusting to life after surgery can be challenging. In fact, emotional changes related to surgical weight loss often overwhelm patients.

“A lot of people are not psychologically prepared for how the world treats them following losing a lot of weight,” says Nicholson. “They aren’t prepared for all the attention. That can be a good thing, but can cause crazy behavior as well.”

To help, many area hospitals offer post-operative support groups. Texas Health Plano, for example, offers twice-monthly support groups; Baylor Plano offers monthly support group. Simons attends both. Sometime she goes to be supported, but often she goes to encourage others.

“I am a faithful participant in the support-group process. … It was a lifesaver,” she says. “[And] if I can be there for someone else, I want to be there. It keeps me focusing on what I need to focus on. It’s key to long-term success.”