About four years ago, the bus hauling Thomas Jefferson High School’s acclaimed band had just arrived at a football game. Band members began filing out with their instruments when one pulled aside band director Tom Woody. The student told him that two kids at the rear of the bus had snorted cheese heroin on the ride over.

Today, Woody says that is the first time he can recall that a student at TJ had ever told on a classmate who had used cheese. That might have been the turning point.

Cheese is a mixture of Mexican black tar heroin and over-the-counter cold medicine, usually Tylenol PM. The Tylenol is added to make the gummy heroin suitable for inhalation and because one of its active ingredients, diphenhydramine, works synergistically with heroin to create a more wicked—and unpredictable—high. Too, it dilutes the heroin so that one dose of cheese could go for as little as $2, perfect for high school students without a lot of money. At the height of the cheese epidemic, in fact, the Dallas Independent School District caught an 11-year-old student with the drug.

The world learned about cheese in 2007. Cutting heroin with cheap additives was nothing new; Plano made national headlines in the 1990s when dozens of kids died from using heroin, some of which had been mixed with sleep aids. But Newsweek focused media attention on Dallas in the summer of 2007, saying that the Drug Enforcement Administration was worried that use of the drug would spread across the country. The cheese scare was centered in Northwest Dallas, where kids were dying. And that made TJ—in the heart of northwest Dallas, on Walnut Hill Lane—ground zero. Cheese was first found on the campus in 2005, when a hall monitor discovered a student hiding the powder in a bottle of Tylenol PM. The drug was so prevalent there that the school had a nickname that even TJ students used: the Cheesehead Factory.

When it was bad, some TJ students were using cheese throughout the day, maybe as many as 10 times. They snorted in the bathroom stalls and at their desks. A student overdosed at her desk and had to be resuscitated by her teacher. DISD Police detective Sergeant Jeremy Liebbe, who has been with this district nearly eight years, was testing powder so regularly that he installed a small drug analysis lab in his office. Kids sat at Liebbe’s desk, begging to get off it. Others had no idea they were snorting heroin. They just knew it was called cheese, was cheaper than pot, and lots of TJ classmates had tried it. Liebbe kept his eye on kids who seemed particularly sleepy or whose folders bore Chuck E. Cheese’s stickers.

The whole thing took a toll on Cathleen Cadigan. The social studies teacher had once been so upbeat about TJ’s kids. She didn’t want to imagine them hiding heroin in their bra straps. “I felt completely powerless,” she says. But when you’re training to teach history, no one tells you that you should know how to resuscitate a student who ODs in class.

“I think at that point, our students were just sick of it,” Woody says.

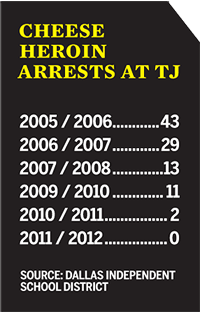

Now things are different. A sweeping regime change and self-policing students have dramatically reduced cheese use at TJ. During the 2005–2006 school year, DISD police arrested TJ students 43 times for cheese. Two years later, the number dropped by half. Last year, there were just two arrests.

“I have not heard the phrase ‘cheese’ in a long time,” says DISD Police Chief Craig Miller. “I know we’re not arresting kids for it, or at least not as much.”

Were it up to Principal Edward Conger, TJ would have a sailing club and be totally cheese free. He realizes either prospect may be unrealistic. Tall, white-haired Conger spent 20 years as a Marine and three years ago ushered in a militant approach to discipline, beginning at the front lines: homework. You skip your homework, you stay until 6 pm to finish or you walk 12 laps around the track. In the beginning, Conger estimates, 40 percent of students regularly completed their homework. That figure now is up to 85 percent.

Student responsibility wasn’t the only problem. After settling into the front office, Conger says, he let go two staff members—a sliver of TJ’s 125—who reacted more as “friends” to students found with cheese than as disciplinarians. “Their version of treating the problem was to communicate with the kid,” he says. Everyone had to get on board, not just the students.

Another crucial step was bringing on board the Dallas Council on Alcohol & Drug Abuse. “We knew it was the school that was getting a lot of the attention,” says Alison Watros, the council’s prevention programs director. She and other treatment experts initiated a social norms campaign at TJ, conducting focus groups to assess the problem. Students were asked: how many of your fellow students do you think use

it? How harmful do you think cheese is? Do you use it?

The answers became a focus of the school’s new “street team” of about 20 students, led by Cadigan and school nurse Carole Taylor. For Taylor, cheese wasn’t just killing students at her job. It was killing the school she had graduated from 30 years ago. Taylor, who spent 15 years at Parkland before coming to TJ, keeps a tattered 2007 issue of D Magazine with a story describing the drug’s hold on TJ. Taylor makes students read it, to remind them of where TJ has been. Her small office is cluttered with papers, but she finds a picture of the street team smiling on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. These are the students credited with turning around TJ.

At Vanessa’s first meeting, three years ago, she made a brave admission. She’d almost skipped the meeting, convinced her family drama meant she didn’t belong. Wouldn’t the others think she was a hypocrite? The previous day, her brother had been arrested with other TJ students for possessing cheese. Telling the story now, her voice grows shaky. She’s been practicing telling it without crying. She misses her brother, who hasn’t lived with her and her mother since 2008.

On the day of her brother’s arrest, she told her mother that she was going to quit the street team at TJ. Vanessa’s declaration lingered in the air that night, as Rose Lopez drove home from school. Then her mother broke the quiet.

“Don’t you want to help other students?” Rose asked.

The next day, Vanessa sat quietly with her new, unknown team. They were already talking about the busts. She stood up and said sheepishly, “My brother was one of the ones arrested.”

Then another girl revealed cheese had affected her family. Vanessa wasn’t alone, as she’d imagined. She threw her relief into the team, which created an anti-cheese slogan and graphics. For five weeks after school, they made buttons and T-shirts. Seemingly random numbers and phrases began popping up all over school. “90.6” on posters. “Own” written in icing atop free cookies. Vanessa liked being part of the secret. Finally, a healthy one.

Once curiosity was piqued, the team spoke to classes, revealing the message: “Own your life. Own your future.” The poster stat, 90.6, was the percent of students surveyed who said they hadn’t used cheese.

After the team’s blitz, second-year surveys showed a 1 percent decline in students reporting cheese use. With enrollment at more than 1,300, that meant 13 lives had been potentially saved. Last May, 95.3 percent of students reported not using cheese.

There is still a lot of work to be done. TJ is hardly squeaky clean. In 2009, a 15-year-old TJ student died from cheese, the last suspected DISD overdose. Last October, a 17-year-old girl admitted to administrators that she had used cheese.

So as the members of the original street team graduate, they’ve been recruiting new members. Vanessa hopes to study applied behavior analysis at the University of North Texas, to learn why people make the decisions they do, like taking drugs. The team’s success still surprises Watros, who says she never thought the campaign would last this long.

“TJ’s put a lot of effort into this. It’s really not the Cheesehead Factory,” she says. “The kids are really proud of their school.”

Write to [email protected].